Alfred McClung Lee (August 23, 1906-May 19, 1992) and Elizabeth Briant Lee (September 9, 1908-December 9, 1999) were leading 20th-century sociologists who published breakthrough studies of propaganda, race, and media. They also authored textbooks; founded two professional organizations and were outspoken advocates for freedom, democracy and equality.

Elizabeth was the third child of Adah May and William Wolfer Briant. Her father was head of communications at a Jones and Laughlin Steel plant in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania until he was laid off during the depression. Raised a Baptist in a competitive family that held education in high esteem, Elizabeth graduated at the top of her high school class and was awarded a college scholarship.

Alfred’s father, a lawyer, lived in suburban Oakmont, Pennsylvania and commuted by train to his Pittsburgh office. Something of an idealist he often defended the poor and the powerless. As a child, Alfred sang in the choir at the St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Oakmont.

Alfred met Elizabeth Riley Briant on a blind date at the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) where Alfred (Al) was an English composition and mathematics major. After he graduated in 1927, they were married in the Episcopal Cathedral of Pittsburgh. Elizabeth (Betty) received her degree in English literature two years later.

Both stayed at Pitt for graduate study. Al wrote for local newspapers while Betty worked as a graduate assistant; he pursued a Master’s in journalism while she continued on in English. Both took and enjoyed courses in sociology, a relatively new field of study. Her Master’s thesis, “Personnel Aspects of Social Work in Pittsburgh,” surveyed the needs and accomplishments of this new profession and was instrumental in the establishment of a social work department at Pitt. Al’s thesis, “Trends in Commercial Entertainment in Pittsburgh Newspapers: 1790-1860,” explored print advertising using a variety of statistical and sociological research methods.

When Al won a scholarship reserved for a “son of an Alleghany County lawyer,” he applied to Yale and was accepted into the Sociology and Anthropology doctoral program. Betty applied and was also accepted.

At Yale, Al supplemented his scholarship income by working part time as a reporter for the New Haven Journal-Courier. When Betty became pregnant in 1934, she temporarily dropped out of school; not one to be idle, she used that time to type and edit Al’s doctoral dissertation, “A Sociological Analysis of the Daily Newspaper in America.” It was published in 1937 as The Daily Newspaper in America; the Evolution of a Social Instrument, and was still quoted and still in print in 2000.

In 1934, Al took a teaching position in the journalism department at the University of Kansas at Lawrence. Al’s three years at Kansas were exciting. He respected his student’s mastery of their craft, but challenged them to examine issues in depth and to voice their opinions. Al and Betty also encouraged and supported an anti-war student group that was satirically named the Veterans of Future Wars (VOFW). It didn’t take long before some Kansans were calling Al the “Socialist Professor” and agitating for his removal. Betty continued to work on her Yale dissertation while in Kansas but she felt isolated, being neither an academic nor a stay at home mom. When a job offer came to Al from Yale they moved back east.

Betty completed her Yale doctorate in 1938, shortly before the birth of their second son, Briant Hamor Lee. Her dissertation, “Eminent Women: A Cultural Study,” explored the social factors leading to the achievements of 628 women listed in the Dictionary of American Biography. She was awarded a Ph.D. in sociology and anthropology by Yale, only the second woman to receive one. Almost every Yale dissertation, at that time, was published but not hers. Piqued, she barred the interlibrary loan of her dissertation. Unaccessable and unpublished, this pioneering feminist work would go unnoticed by feminist and women’s studies researchers. Years later, Betty still recalled and still resented the mocking devaluation of her work by the male faculty.

After an unproductive year at Yale, editing (ghostwriting) a book for another scholar, Al went on the job market. New York University (NYU) hired him in 1938, but only to teach one marketing course. He supplemented that by working for the public relations firm, Raymond Rich, and with the Institute for Propaganda Analysis. In 1939 he received a full time appointment at NYU.

At the Institute for Propaganda Analysis, Al defined the common techniques of propaganda, i.e. flag waving, band wagon, grandstanding, etc. These definitions and their symbols were introduced in the 1939 book, The Fine Art of Propaganda; a Study of Father Coughlin’s Speeches, coauthored by Al and Betty. Father Coughlin was a depression era demagogue whose radio broadcasts reached up to 40 million people. Al served as the institute’s Executive Director; 1940-42. (Another prominent foe of Father Coughlin was Unitarian minister Walton E. Cole.)

Speaking at the Williamstown (Massachussetts) Institute of Human Relations in 1941, Al urged participants not to discriminate against citizens who were, “…Negroes, of German Extraction, of Italian descent, of Jewish religious beliefs, of oriental stock or of Mexican origin.” During WWII, Al was a conscientious objector. On the other hand, his brother, George, was a career military officer with a Ph.D. in engineering. George taught at the Naval Academy, worked in the Pentagon, and retired as a three star general. Al and George would meet for lunch occasionally but were not close. Both of Al and Betty’s sons were conscientious objectors during the Korean and Viet Nam wars (Al called it the Indochinese Undeclared War).

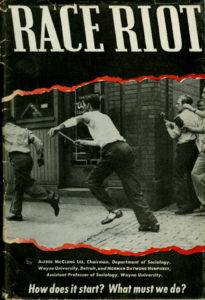

In 1942 Al was asked to chair the Sociology Department at Wayne University (now Wayne State University) in Detroit, Michigan. Al and Betty arrived with two young boys shortly before a race riot broke out in Detroit at Belle Isle Park in June of 1943. On foot, Al visited affected neighborhoods and talked to participants. An armed encampment, with earthen work walls was set up in the playground of their son’s public school. After 3 days of black-white confrontations and 34 deaths, the Michigan National Guard restored order. Out of this situation emerged the 1943 book, Race Riot, written by Al and Norman Humphrey. The book notes that “such riots soil the international reputation of American democracy, and most significantly, represent a real danger to democracy itself.” In 1964 when Detroit burst into flames with renewed racial and civil strife, Al renewed his call for reconciliation in a timely addendum to the re-issuance of Race Riot, 1968.

The Lees wrote a number of college textbooks. Al and Betty co-wrote, Social Problems in America: a Source Book, 1949; and Marriage and the Family, 1961. Al edited a textbook New Outline of the Principles of Sociology, 1946; and he authored Readings in Sociology, 1951; Fraternities without Brotherhood: a Study of Prejudice on the American Campus, 1955 (Beacon Press); and Multivalent Man, 1966.

In the early 1940s, Marshall Field paid Al $20,000 to ghost-write Freedom is More Than a Word, published in 1945. Field also funded a 1947 grant that provided Al with the release time needed to research and write How to Understand Propaganda, 1952. Later on, Al and Betty would fund their own research projects, shunning sponsors and outside interference.

The Lees were active in the First Unitarian Church of Detroit during the ministry of Tracy Pullman, who became a close friend and spiritual advisor. Al worked with the American Civil Liberties Union, served as vice-president of the Detroit Council of Churches and was active in a variety of social service organizations. As a consultant he worked with the emerging labor unions of Detroit, including the United Auto Workers (UAW), under Walter Reuther. His Wayne State students initiated a series of detailed sociological and demographic population studies in the Detroit metropolitan area; studies that continued into the 21st century.

Betty lobbied against the introduction of pari-mutuel betting in Michigan after the family moved to suburban Northville in 1946, site of a race track. In the 1940s there was widespread corruption and intimidation in Michigan politics and law-enforcement, a state senator was murdered, a Northville anti-gambling activist’s plant was fire-bombed, and UAW President Walter Reuther along with his brother Victor were injured in separate shotgun attacks. It would be years before Betty could talk about the atmosphere of fear in Michigan caused by the shootings, fire-bombing and violence that came so close to her family.

In 1949 Al was appointed to head the Sociology and Anthropology Department for the Brooklyn College campus of the City University of New York. Al and Betty had been active in the American Sociological Society as well as the Eastern Sociological Society and were ready to go back east. Their new home was just around the corner from the First Unitarian Church of Brooklyn Heights.

Al continued to research and write about race relations in America. As department head at Brooklyn College he implemented a faculty hiring program to insure race and gender diversity. Reporting in the Christian Register in 1954 as chairman of the Commission on Unitarian Group Relations, Al said: “…our churches would be immeasurably enhanced by becoming genuinely inclusive, interracially and culturally, so also would our ministry be enriched if we would say to black and yellow as well as to white: The doors of opportunity to a life of service are open… you will be judged solely as an individual; you will be weighed upon merit alone. Our people are color-blind. What you are matters tremendously; the pigmentation of your skin matters not at all.”

In the early 1950s, Al was active in the New York NAACP and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Meeting and befriending Kenneth Clark, Thurgood Marshall, and James Coleman led to his involvement as an expert witness in the school desegregation litigation that culminated in the 1954 U. S. Supreme Court Brown decision.

In 1951 the Lees started the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) to improve working conditions, protect academic freedom, and to encourage sociological researchers to address society’s everyday concerns. The Lees wanted sociologists to be involved with people’s problems and to formulate solutions and initiate action to promote social justice and welfare. The Lees thought that mainstream “value-free” sociologists spent too much time manipulating statistics, raising funds, and publishing articles instead of getting involved in people’s lives, staking out moral positions and intervening to solve problems.

Al and Betty were instrumental in founding and nurturing three other organizations that appealed to activist and radical sociologists who didn’t share the mainstream values exemplified by the American Sociological Society (ASS) or the American Sociological Association (ASA). These included the Union of Radical American Social Scientists; the Society of Humanist Sociologists, 1976; and the Clinical Sociological Association, 1978.

Over the years, Al served terms as president of the ASA, SSSP, Association for Humanist Sociology (AHS), Eastern Sociological Society (ESS), and the Michigan Sociological Society. Betty served as president of the AHS, vice-president of the SSSP and secretary-treasurer of the ESS. In 1976 Al was elected president of the American Sociological Association in a write-in campaign spear-headed by younger sociologists tired of “old guard” conservatism. Al’s presidential address, an indictment of the “sociological establishment” got a mixed reception; the younger sociologists cheered while the older members walked out in disgust.

Betty held a number of teaching positions in addition to her work as wife, editor, mother, and co-author. She was a lecturer in the school of nursing at Wayne State, 1944-46; lecturer in sociology at Brooklyn College, 1949-50; lecturer at Hartford Seminary, 1951-53; visiting professor in sociology and anthropology at Connecticut College, 1953-1954; and lecturer in sociology and anthropology at Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1962-1966.

Betty worked at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan, Italy while Al was Director and Professor at the UNESCO Center for Sociological Research in Milan, 1957-1958.

Al taught at the University of Rome on a Fulbright fellowship, 1960-1961; and both spoke and presented papers at a number of international conferences. These trips broadened their influence among international sociologists, as well as affecting their own world view of social institutions.

In 1961, the Lees moved to Short Hills, New Jersey about 20 miles west of New York City. After Al retired in 1971 they devoted even more time to research and writing. Their interest turned toward a more explicit humanist sociology with their home becoming a center of discussion and debate among visiting sociologists. Al and Betty remained active in sociological societies; continued to travel to conferences and present papers; and continued their output of book reviews. Chapters that Betty wrote on propaganda, women in sociology, women in academia, and the history of sociology appeared in a number of essay collections and textbooks.

Al wrote, Multivalent Man, in 1966 exploring the multiplicity of roles or “masks” which people use in different social situations. In his 1973 book, Toward a Humanist Sociology, Al argues that spreading knowledge of sociology principles would empower more than just the elites while his book Sociology for Whom, 1978, encouraged sociologists to do more “participant observation.” In 1978, Betty and Al played key roles in the founding of the Clinical Sociology Association. The Lee’s had advocated the practice of “clinical sociology” ever since 1944, when Al first defined the field in H.P. Fairchild’s Dictionary of Sociology.

The Lees, who were both of “Scotch-Irish” background first visited Ireland in 1955, returning nine more times. Out of this grew Al’s book, Terrorism in Northern Ireland, 1983, which explored the class, race, political, and religious components causing and perpetuating the strife in Northern Ireland.

According to Betty, “both together in everything,” described their relationship. Betty and Al were Unitarians, Quakers and Humanists. They both signed Humanist Manifesto II in 1973. “No deity will save us; we must save ourselves,” it declares, “Religions that place revelation, God, ritual or creed above human needs and experience do a disservice to the human species.”

Sociology for People: Toward a Caring Profession, published in 1988 when he was 82 years old, was the last book Al would write. In it he examines the ways that sociology can support the rank and file, helping them emancipate themselves from manipulation by elites. Three years later, at the age of 85, Al made his last conference presentation with Betty, “Struggles Toward Equality and Justice,” at the 1991 SSSP convention. He died the next spring at home in Madison, New Jersey. Betty died seven years later.

Since 1981 the Society for the Study of Social Problems has awarded the annual “Lee Founders Award” to recognize members whose career achievements exemplify the ideals of the society’s founders, especially the humanist tradition of Alfred McClung Lee and Elizabeth Briant Lee. In 2001, the Alfred McClung Lee Sociology Professorship and Library Resource Collection were endowed at the University of Kansas by a student that Al had taught for one class, back in 1934. The endowed chair’s purpose is, “to promote tolerance and fight anti-Semitism and prejudice.”

The Papers of Alfred McClung Lee; including correspondence, manuscripts, research notes and clippings are in the Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections. Some of Elizabeth Briant Lee’s papers are archived with her husband’s papers at Brooklyn College.

In addition to the books mentioned above, Al and Betty wrote hundreds of book reviews, essays, pamphlets and journal articles. They were regular contributors to, The American Sociological Review, Christian Register, Friends Journal (Quaker), Journal of the Liberal Ministry, UU World, Fellowship (Fellowship of Reconciliation), The Saturday Review of Literature, The Nation, The Churchman, In These Times (Socialist), Journalism Quarterly, Editor and Publisher, The Quill, Public Opinion Quarterly, The Humanist, Scientific Monthly (American Association for the Advancement of Science), and the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

A detailed biography, Marginality and Dissent in Twentieth-Century American Sociology: The Case of Elizabeth Briant Lee and Alfred McClung Lee, by John F. Galliher and James M. Galliher examines their careers from an academic perspective. It includes an exhaustive bibliography.

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted June 7, 2011