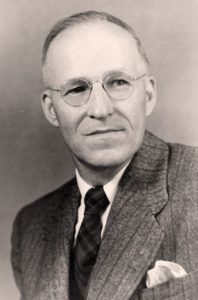

Angus Hector MacLean (May 9, 1892-November 11, 1969), Universalist minister, theological school professor and dean, played a major part in reshaping the philosophy and practice of religious education within the Universalist and Unitarian denominations during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. He was born into a Scottish Presbyterian* family in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the eighth of nine children of Neil and Margarite (MacRae) MacLean. As a young man he was a Presbyterian lay missionary on the prairies of Western Canada, c.1910-16. An orderly with the Canadian army during the first World War, he cared for the wounded following the devastating explosion of an ammunition ship in Halifax harbor and served near the front lines in France. MacLean then prepared for the Presbyterian ministry at McGill University and its theological school, the Montreal Cooperative Theological College. Initially, he was denied ministerial fellowship because of his liberal views, but the decision was reversed after the fellow members of his graduating class protested.

In 1922 Angus MacLean married Ruth Rogers, a feminist and a liberal in religion and politics. Together they enjoyed a close and rewarding relationship for the next 47 years. The couple were parents of a son Colin and a daughter Susanne—Susanne and her husband Gary Boone became dedicated Universalists. MacLean was a man of broad interests—education, theology, administration, campus affairs, oil painting, outdoor activities, and spectator sports, especially ice hockey. The family spent their summer vacations at a primitive camp on an isolated pond in the Maine woods.

MacLean’s academic career stretched from 1924 until 1960—first as an instructor at Columbia University Teachers College, 1924-28, then as professor of religious education at the Theological School of St. Lawrence University, 1928-60, and as dean, 1951-60. In addition to earned A.B. and B.D. degrees from McGill, and an M.A. and Ph.D. from Columbia, he received honorary doctorates of divinity from three Universalist and Unitarian schools: Tufts, Meadville, and St. Lawrence. In 1945 he acknowledged his break with traditional Christianity when he was ordained by the Universalist Church of America. When the Federal Council of Churches denied admission to the U.C.A. in 1942 and again in 1944 on theological grounds, MacLean commented, “After being turned down twice as not being good Christians, we decided we should look somewhere else.”

Perhaps the greatest of Angus MacLean’s many contributions was as a teacher, respected and beloved by his students throughout his long tenure at St. Lawrence. One of his students, Richard Gilbert, was to write later, “Angus was a teacher without peer. He involved his students in the rich variety of activities which he believed characterize any good classroom. I still treasure a small red jar which began life as a piece of clay which I ‘threw’ on the potter’s wheel and later fired on the kiln which Angus [had] acquired.” Always available, he found no need to keep office hours. His wife Ruth reported that “One night about one thirty our doorbell rang loudly. We grabbed our robes and rushed downstairs thinking it might be an emergency. We opened the door and there stood two students hand in hand. They looked starry-eyed. ‘We have decided to get married and we wanted you to be the first to know.'” Once, when after a long, hard winter, spring fever had overcome his students, he moved his religious education class outdoors for a long afternoon bird walk along the St. Lawrence River. Following his retirement as dean an endowed chair was established in his name at the school.

Through his teaching, writings, and speaking engagements MacLean became recognized, along with Sophia Fahs and Ernest Kuebler, as one of the three leading religious educators in the liberal religious movement. His views on education and religion are well reflected in his writings. His doctoral dissertation, The Idea of God in Protestant Religious Education, 1930, was a devastating critique of the situation that then existed. The New Era in Religious Education, 1934, promoted a child-centered, experience-centered, rather than a Biblical-centered, approach. “The Method is the Message,” first delivered in 1951 and republished in 1962, was a milestone address, asserting that how religion is taught is more important than what is taught. The Wind in Both Ears, 1965, was the product of his mature thought on religion and its evolution, and on the strengths and weaknesses of Unitarian Universalism.

Although MacLean moved well beyond the Presbyterianism of his upbringing, he acknowledged its importance. “There was an ethical core there that became my core,” he wrote. “Time was to change my ideas about God, the Devil, the Bible, and the Sabbath, but integrity, honesty, truth-telling, and the overwhelming sense of the sovereignty of whatever made and governed life, no matter how named, were in my guts as in my mind, and not to be ousted.” He also recognized that orthodox theological categories had their origins in human experiences. The idea of “grace” was especially important to him, rooted in his recognition that he was the recipient of important gifts that he had neither earned nor deserved. MacLean also acknowledged the importance of his Scottish heritage. “One thing is sure, the Celt never takes life superficially. He may glory in it or fight its limitations like a Dylan Thomas, but he never ignores it or repudiates it, and is not likely to lose a sense of contact with the source of life or the controller of destiny.”

The evolution of MacLean’s religious thinking was by no means been a smooth one. He reported that at one point he found himself depressed, his old faith gone, living in a theological void. Later, while contemplating a patch of swampy ground, he suddenly perceived it as a profound creative source: “‘What a marvelous ooze,’ I said—and I had my God again!” But he never accepted the idea of God easily. “There is a ‘God’ with whom I feel identified,” he wrote, “and there is also the God to whom I respond ambivalently, and with whom I keep up certain quarrels.”

Following his retirement from the deanship, MacLean accepted a call as minister of religious education at the First Unitarian Church of Cleveland in Shaker Heights, Ohio. It proved a fitting and fulfilling capstone to his career. In 1968, he and Ruth retired to Manlius, New York, where parishioners from the Shaker Heights church had helped construct the couple’s new home next door to their daughter and son-in-law. After his death the following year, a family service was held there, led by Richard Gilbert, a former student. This was followed by a public service at the Shaker Heights church, at which Max Kapp, his successor as dean at St.Lawrence, offered the eulogy. In it Dean Kapp aptly focused on Angus MacLean’s contribution as a religious educator: “His quiet and humble demeanor concealed a dynamic and courageous creativity which made him an outstanding leader in introducing the new religious education. . . . He was a champion of the spiritual rights of children and a wise interpreter of the liberal spirit to their parents.”

In 1971 the alumni association of the theological school established the Angus H. MacLean Award for excellence in the field of religious education. Since then it has been presented annually at the U.U.A. General Assembly.

* NOTE: The Presbyterian church where his family worshipped when he was young has been transported to the Clachan Gaidhealach Highland Village museum on Cape Breton.

Some papers of Angus MacLean can be found in the Universalist Collection at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts and in the MacLean Collection at Meadville/Lombard Theological School in Chicago, Illinois. MacLean wrote three autobiographical books: The Galloping Gospel (1966); I Began in Cape Breton (1969); and God and the Devil at Seal Cove, published posthumously in 1976. In addition to the works mentioned above and in the body of this article, he was the author of numerous articles and pamphlets. MacLean is discussed in Russell Miller’s The Larger Hope, vol. 2 (1985); in Max Kapp and David B. Parke, 120 Years: An Account of the Theological School of St. Lawrence University, 1856-1976 (1976); Richard S. Gilbert’s unpublished 1995 John Murray Distinguished Lecture, “The Galloping Gospel According to Angus Hector MacLean”; and David B. Parke’s Boston University Ph.D. dissertation, “The Historical and Religious Antecedents of the New Beacon Series in Religious Education (1937),” on the contributions of MacLean, Fahs and Kuebler (1965).

Article by Charles A. Howe

Posted March 31, 2001