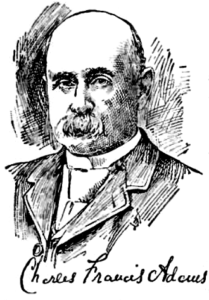

Charles Francis Adams Jr. (May 27, 1835-May 20, 1915) was a lawyer, writer, railroad regulator, arbitrator, journalist, railroad president, and soldier. Reared a Unitarian, his beliefs changed as he took stock of his life after the Civil War. Like many Unitarians he was influenced by new social and political theories and European philosophy. As an adult, he continued to participate in Unitarian church activities but not as much as his father.

Charles Jr. was the third child of Charles Francis Adams, Sr. and Abigail Brooks Adams. She was the youngest daughter of the wealthy Unitarian Peter Chardon Brooks and Anna Gorham Brooks, the daughter of the first president of the Continental Congress. The Adams family lived on Hancock Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts where he attended several small private schools starting with a dame school. He enrolled in Boston Latin School when he was 13.

Born into a successful family, it took perseverance to find and follow his own calling. His great-grandfather, John Adams had been President of the United States as had his grandfather, John Quincy Adams. His father, Charles Francis Adams, Sr.—lawyer, politician, diplomat, and writer—had a distinguished career as a diplomat. Two of his brothers, Henry Adams and Brooks Adams were historians, social critics, and writers while a third, John Quincy Adams II was a Democratic politician in Massachusetts.

In 1851 when he had problems in school, his father hired a tutor to prepare him for Harvard. He soon entered in the sophomore class. The Harvard faculty at the time was dominated by Unitarians. His teachers included James Russell Lowell—the successor to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—teaching modern languages; Benjamin Peirce teaching mathematics; C.G. Felton who specialized in natural religion, moral philosophy and political science; and Francis Bowen teaching history and philosophy. Adams enjoyed his clubs; Hasty Pudding chose him as secretary and poet. He also found time to read Emerson and Hawthorne. Although he won one of Harvard’s most prestigious awards, a Bowdoin Prize for an essay, he graduated in the lower half of his class.

After graduation in 1856 he studied law in the offices of Richard Henry Dana, a Unitarian, and Charles Francis Parker, whose father was a Unitarian minister. Richard Henry Dana’s grandfather had been secretary to John Adams during the War of Independence. Dana, whose biography C.F. Adams, Jr. was to write, was the author of Two Years Before the Mast (1841) and had been one of the attorneys for fugitive slave Anthony Burns.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr. duly passed the bar and opened an office in a building owned by his father. While it is hard to picture an Adams as a man about town, he was just that. Unable to attract clients or earn a living he spent his time socializing with Boston’s social and political elites, a pastime made possible by the Adams family name and money. He lived with his parents and summered at the Adams home in Quincy, Massachusetts. He wrote letters, kept a diary, and reviewed the occasional book.

Visiting his father in Washington, D.C. he met with senators and representatives and saw the north-south conflict first hand. He joined a local Boston militia in 1859 to learn about arms, marching, and military ways. In September Adams and his father joined Senator William Seward on a month-long rail tour of the west, going as far as Lawrence, Kansas. On their return they visited the Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln at his home in Springfield, Illinois; Stephen Douglas in Toledo, Ohio; and other politicians along the way. After the great celebration of Lincoln’s election Adams noted that, “My own impression is that the experiment of secession is about to be tried.” He attended the inauguration in March 1861. A month later his first mature essay, “The Reign of King Cotton,” appeared in the April 1861 Atlantic.

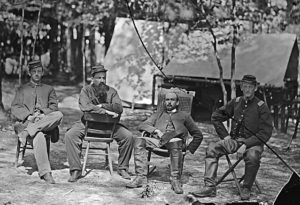

His law practice was going nowhere. He looked after his father’s Boston properties while his father was in England serving as U. S. ambassador. Adams fretted about joining the Army for six months. He finally applied for a lieutenant’s commission with the First Massachusetts Cavalry. At the beginning of 1862 he was stationed in New York and then Port Royal, South Carolina. Once there he felt he was poorly trained, as were most of those around him. In September 1862 he saw his first fighting at James Island as an aide to Robert Williams, a West Point graduate. A year later Adams was promoted to captain. He fought at Antietam and Gettysburg and then in 1863 against Lee’s cavalry.

Visiting his sister Louisa in Newport, Rhode Island, while on furlough in 1864 he met and was engaged to Mary Hone Ogden. He also had time to visit London and Paris. Dreading the return to his cavalry outfit, he had an old friend ask Massachusetts Governor Andrew to attach him to the Army of the Potomac Headquarters with Generals Meade and Grant. However, after six months of orderly duty at headquarters he longed to return to action. In September 1864 he was commissioned lieutenant colonel with the black Fifth Massachusetts Calvary under his old friend Henry S. “Harry” Russell.

When Russell resigned, Adams took charge of his regiment guarding a prison camp. Using his influence with Army of the Potomac staff he requisitioned and received twelve hundred horses. “I had the satisfaction of leading my regiment into burning Richmond, the day after Lee abandoned it,” Adams said in his autobiography. A few months later, sick again with malaria and dysentery, he left his command for good and traveled north to Newport. He left the Army and in 1866 President Andrew Johnson made him a brevet, or honorary, brigadier general for his bravery and service. Charles and Mary married in November 1865. They would have three daughters and twin sons. Even when his family had a Boston home, they summered in Quincy. However, he did not attend church as regularly as his father did except for major events such electing ministers, memorial addresses, and funerals.

Not wanting to practice law when the war was over, he thought about his future. In his biography, he mentions how his beliefs changed during that period:

“When in England in November, 1865, shortly after my marriage, I one day chanced upon a copy of John Stuart Mill’s essay on Auguste Comte, at that time just published. My intellectual faculties had then been lying fallow for nearly four years, and I was in a most recipient condition; and that essay of Mill’s revolutionized in a single morning my whole mental attitude. I emerged from the theological stage, in which I had been nurtured, and passed into the scientific. I had up to that time never even heard of Darwin. Inter arma [enim silent leges], etc. From reading that compact little volume of Mill’s at Brighton in November, 1865, I date a changed intellectual and moral being.”

At the end of this bout of introspection, under the usual cloud of living up to the family legacy and his own competitive expectations, he decided that business might be the place to leave his mark on the world and that writing might be the making of his career. Adams, his brother Henry, and other reformers found a ready outlet for their articles in Edward Lawrence Godkin’s new weekly magazine, The Nation.

Believing the age of steam would eclipse the era of the printing press, Adams said, “I…fastened myself, not as Mr. Emerson recommends, to a star but to the locomotive engine.” His article discussing Josiah Quincy’s proposal that Massachusetts take back ownership of its railroads appeared in the North American Review in April 1867. An article a year later published his proposal for a state railroad regulatory commission. Similar articles appeared in the American Law Review and the Journal of Social Science. With no railroad experience and little available data Adams filled these articles with general discussions of the “railroad problem,” and called for a state railroad commission. At the same time, he helped friendly legislators draft commission legislation and then he lobbied for its passage.

His efforts soon led to the creation of the Massachusetts Railroad Commission. Adams was appointed one of three commissioners in June 1869. He confided to his diary, “. . . a two year chase had brought my game down.” The next month the North American Review printed, “Chapters of Erie”, his expose of the railroad speculations of Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, James Fisk, and Daniel Drew. Adams’ portrait of their Wall Street manipulation was an early example of “muck-raking” journalism.

During his ten years on the commission, Adams came to understand the structural problems in the industry preventing any real rate relief for the public. Railroads had high fixed costs for land, rolling stock and equipment which led them to favor large loads being carried long distances. This bias supported, what appeared to the public, to be discriminatory rate structures. Adams concluded that economies of scale would lead to even larger railroad systems and regulated monopolies might be the best way to lower costs and minimize rates.

The lack of enforcement powers stifled the commission. It could only subpoena records and distribute reports. Adams analyzed the data and drafted reports to educate legislators and the public. His work with the commission standardizing railroad law, accounting, and safety regulations was adopted by other states. In 1877 Adams and the commission also negotiated an agreement between labor and management ending the Boston & Maine Railroad strike. The next year his Railroads, Their Origins and Problems, raised his national profile.

In that year President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Adams one of five new “government directors” of the Union Pacific Railway (UP). Representing the public, they served alongside 15 corporate directors representing stock holders. A new law created a special UP auditing bureau in the Department of the Interior leaving the government directors the task of touring the road and reporting on its condition. They did in September and October and Chairman Adams, wrote a 20-page report and submitted it in December. He resigned because the Board of Government Directors had “almost entirely failed to accomplish the results that were expected of it. . . ”

“I was then so much impressed with the value of the road as an investment,” Adams said, “that when I shortly after resigned, as agent of certain persons and adviser of others, I was instrumental in some heavy purchases of the stock.” The physical plant of the railroad might have been impressive but the UP was mired in debt, distrusted by the public, and divided into a number of intertwined corporate entities. In addition, the Union Pacific’s unique government charter left it at the mercy of congressional whim.

Quitting Massachusetts Railroad Commission in 1879, he accepted a position on the Eastern Trunk Line Association board of arbitration . Created two years earlier by four of the largest railroads east of the Mississippi, the association tried to bring stability and order to railroad rates and services through pooling. It was led by Albert Fink, an accomplished civil engineer, railroad manager, and economist. Railroads in the pool avoided cut throat competition by dividing traffic, pooling income, and agreeing to charge standardized rates high enough to cover costs and provide reasonable profits.

Adams joined the UP corporate board and made a long inspection tour of the Union Pacific Railway in 1882. In March 1883 he was asked to chair a committee exploring the road’s management problems. In addition to management problems, they found the UP was operating in the red, its stock price was dropping, and a recession was drying up sources of loans. Later that year, after Jay Gould left the board and Sidney Dillion resigned as president, Congress urged Union Pacific directors to appoint Adams as Dillion’s replacement. Adams seemed like the ideal candidate; he understood railroads, he was honest, he came from a good family, and he knew how to work with Congress and eastern investors. Adams accepted and resigned from the Eastern Trunk Line Association board the following year.

As Union Pacific President, Adams knew what was needed. He attacked internal problems by consolidating operations into departments and bringing in new managers. In Washington he fought pending lawsuits, attempted to refinance government debt, lobbied for favorable legislation, and did his best to deal with hostile legislators and bureaucrats. Unfortunately, most of his initiatives came to naught. With six transcontinental lines competing for scarce freight and passenger business it was impossible to increase railroad income. Rate wars cut into profits, pooling schemes regularly collapsed, debt relief legislation was delayed by investigations rehashing old abuses, and losses curtailed dividends. Without dividends stock prices fell leaving the road vulnerable to Wall street financiers.

Even though Adams was employed by the Eastern Trunk Line or the Union Pacific for most of the 1880s he always found time to speak, pen letters, and write articles. Working from his own office in Boston he could easily attend the monthly meetings of the Saturday Club and stay in touch with Boston intellectual and political circles. In 1881 he chaired the Civil Service Reform Association meeting in Boston, the next year he laid out his plan for a national interstate commerce commission in front of an association of Boston merchants, and in 1883 he delivered Harvard’s Phi Beta Kappa address on higher education reform.

In 1890 money got tight in the east, Baring Brothers collapsed, and the price of UP stock started dropping. Unable to borrow money to keep the railroad afloat, Adams was forced to seek the help of Jay Gould. On November 26, 1890, Dillion replaced Adams as president of the UP and control of the railroad returned to Jay Gould. Adams had done as well as could be expected meeting the challenges that the Union Pacific faced. The railroads had led Gilded Age expansion and prosperity but that ended with the Panic of 1893, the start of a long depression. Many railroads went bankrupt. In October 1883 the Union Pacific went into receivership.

The panic also put the Adams family finances in crisis. Although critical of materialism, Adams had built his own fortune during the “Gilded Age.” He invested in land and stock, often collaborating with his older brother John, often using borrowed money.

Adams and his brothers were deeply involved in the local politics of Quincy, Massachusetts. He was a committeeman for fifteen years while his brother John was moderator for twenty. He was a Republican and John a democrat but together they reformed the town meeting and improved and enlarged town services.

Worried about Quincy’s educational failings, he served on the school committee with his brother. The committee hired Francis Parker, a Civil War Veteran who had studied educational methods in Germany, to reform the curriculum. Some thought Parker was too liberal and resisted his changes but the reforms sparked broad interest throughout the country. Adams wrote a number of articles about them. When he left the school committee after three terms, the governor appointed him to the Massachusetts board of education. His brother Brooks also served there. Adams was also a member of the Board of Managers at the Adams Academy established by his great grandfather President John Adams. Interested in the town library, he was involved in building a new building designed by H.H. Richardson and landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1880.

As Quincy grew and changed over the years Adams grew increasingly disturbed; immigrants were gaining political power, the town was more industrial, and the local landscape was being devastated by the granite quarries. His pride was hurt as newcomers forced old Yankees out. He didn’t join the “Know-Nothings,” but anti-Catholic and Nativist sentiments crept into his works. Finally, in May of 1893 he sold his house on Quincy’s President’s Hill and moved to rural Lincoln.

Adams served on the Harvard Board of Overseers, 1882-1907. Harvard President, Charles W. Eliot initiated a number of reforms during this period. Adams supported changing language requirement and abolishing English A. Describing himself as “socialistic,” he championed tuition increases for the wealthy and more assistance for the less advantaged.

His two-volume Richard Henry Dana: A Biography, was published in 1891. This was quickly followed by his innovative local history, Three Episodes in Massachusetts History (1892), and the historiography, Massachusetts: Its Historians and Its History (1893), a book that praised neither the founders nor the historians.

In 1893, Adams drafted the report of a General Court open space commission. The principle adviser was Charles Eliot, the Harvard President’s son, who had joined Olmsted’s landscape architecture firm. The successful report was widely read. It culminated in a Metropolitan Park Commission that put Adams at its head. The Park Commission’s public works helped workers displaced by the 1893 panic, foreshadowing similar efforts during the New Deal.

At the turn of the century Adams helped organize the Boston Anti-Imperialist League. His beliefs about American foreign policy were similar to his brother Henry’s but differed from brother Brooks’. The Spanish-American War had left America with foreign possessions. Adams said, “We are blood guilty; and we are doing to others in violation of our traditional policy and all the teachings of history what we have protested against when attempted on us or doing elsewhere…I feel I ought to bear witness.”

His remarks about race were more problematic than his anti-war statements. In his autobiography, Adams concluded that “… the negro was wholly unfit for cavalry service, lacking absolutely the essential qualities of alertness, individuality, reliability and self-reliance.” In speeches, he praised Robert E. Lee as an American patriot because his surrender averted possible last-ditch guerrilla and bush-whacking efforts by Confederates. Apparently, Adams didn’t notice Klan intimidation, voter suppression, the terrorism of lynchings, and the widespread use of debt peonage to replace slavery.

During the last weeks of the 1908 presidential election campaign Adams delivered a speech in Richmond, Virginia, “The Solid South and the Afro-American Race Problem.” He began by saying, “And so I propose on this occasion to handle the dynamite referred to [in the speech title] with a freedom bordering on recklessness.” Fulfilling that promise, he said that reconstruction was “worse than a crime,” and suggesting that the solution to the “Negro Problem” should be, “worked out in the south,” without “external intervention.” W.E.B. DuBois responded by letter, telling Adams he was “. . . not only wrong but distinctly sensational in the worst sense of the term.” DuBois found it astounding, “That a man of the twentieth century would stand up and indiscriminately vilify one hundred and fifty million or more human beings. . .”

Adams served as president of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1895-1915; and the American Historical Association, 1901. During 1912, the year the Titanic sank, and Henry had a stroke, Charles Francis, Jr. published his own autobiography. His lecture career reached its apogee at Oxford with his 1913 Rhodes Scholarship address “Transatlantic Solidarity.” Traveling in Europe he scoured archives for a projected biography of his father. Although he wrote a short biography of the Civil War diplomat, he drowned in material and worked on a longer version until his death in 1915. Charles Francis Adams, Jr. is remembered, but his reputation doesn’t match that of his brothers Henry and Brooks, let alone his grandfather and great-grandfather, both of whom served as President of the United States.

Death

Adams died of stroke during a bout with influenza in Washington, D.C. His funeral was at the Quincy church, and he now lies near his brother John in Mount Wollaston cemetery. Eight months after his death, the Massachusetts Historical Society held a memorial service at First Church, Boston. Henry Cabot Lodge, his old student, was the principal speaker. His wife Minnie lived until March 23, 1935. She rests near him.

Sources

The Charles Francis Adams, Jr. papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. Letters, annual reports, and some corporate documents related to Adams are in the Union Pacific Collection of archives and photographs housed at the Union Pacific Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Letters to fellow railroad executives Charles Elliott Perkins (son of James Handasyd Perkins) and John Murray Forbes are in the Newberry Library in Chicago, Illinois.

His memoirs, Charles Francis Adams, 1835-1915: An Autobiography (1916), is useful but somewhat myopic. The standard work of biography is the somewhat dated, Edward Chase Kirkland, Charles Francis Adams, Jr. 1835-1915: The Patrician at Bay (1965). Additional information can be found in Martin B. Duberman, Charles Francis Adams 1807-1886 (1961); Paul C. Nagel, Descent from Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family (1983); Francis Russell, Adams An American Dynasty (1976); and Jack Shepard, The Adams Chronicles: Four Generations of Greatness (1975). A short biography with emphasis on his railroad service is found in Don Snoddy, “Charles Francis Adams, Jr.” in Richard L. Frey, ed., Encyclopedia of American Business History and Biography: Railroads in the Ninetenth Century (1988). Thomas K. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation (1984) covers his time with the Massachusetts Railroad Commission and the eastern pool. Adams’ railroad career also receives extensive coverage in Richard White, Railroaded: the Transcontinentals and the making of modern America (2011). For more on Adams’ views on race see Philip A. Klinkner with Rogers M. Smith, The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America (1999) and Julia E. Johnsen, ed., The Negro Problem in America (1921). An early view of his time with the Union Pacific Railway in found in Henry Kirke White, History of the Union Pacific Railway (1895). Widely covered in the press, extensive reports of Adams can be found in the New York Times, Boston Post, and Chicago Tribune.

Article by Wesley V. Hromatko

Posted March 30, 2015