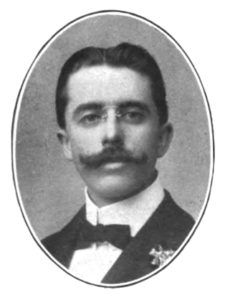

Clarence J. Harris (March 16, 1873-November 27, 1941) was a minister who served both Universalist and Unitarian congregations. During the early years of the motion picture industry, he wrote hundreds of screenplays. He also organized military-style youth groups, animal welfare organizations, a screenwriter’s school, and summer camps for boys.

Harris, the youngest of eight children, was born in Northbridge, Massachusetts to Thomas and Caroline Harris. After graduating from Revere Lay College in Massachusetts and Bangor Theological Seminary, he served Vermont Congregational churches at Windham, Colchester, and Putney during the 1890s and at Crown Point, N.Y., 1899-1900. By 1901, he was in Atlanta as a professor at the Atlanta Congregational Seminary. While there he made a missionary tour of the South, an experience that left a deep impression and would later figure in lectures and sermons illustrating “the quality of cracker and negro preaching.”

In 1902, while still in Atlanta, Harris converted to the Universalist Church. His first assignment was at Winchester, New Hampshire, where he presided during the centennial celebration for the Winchester Profession. In 1904 he was back in Atlanta as pastor of the Universalist Church. Newspaper accounts of his sermons show him, for the most part, expounding on passages from the Gospel and Epistles without controversy. He would at times, though, decry the Pharisaical behavior of some fellow Christians, and a week-long controversy filled The Atlanta Constitution when he sparred with other ministers and the mayor after claiming that the city and its churches turned their eyes from the needs of Atlanta’s poor.

He moved to the Universalist Church in Sharpsville, Pennsylvania in 1905 where he preached a more a liberal theology. In contrast to his Atlanta sermons, Harris wrote in 1908 that in his three years of preaching in Sharpsville he had “never preached anything save the most liberal thought,” with his sermons ranging from “Freethought” to “Socialism.” One reviewer of The Liberal Pulpit, a sermon collection, said it was “radically liberal for a church paper, and is well worth reading by non-church Liberals.” In explaining the difficulty in attracting fellow Freethinkers to his church, Harris noted his undeserved reputation locally as an “infidel” and someone who “denies Jesus” and who “ought to be in hell.” During the May 1908 Billy Sunday revival in Sharon, Pennsylvania, Harris was the only local minister held up for ridicule with his “entrance into hell by an elevator” described by that fiery evangelist. Despite the radicalism of his sermons, he enjoyed support within Sharpsville; the Universalist church trustees are listed as publisher of The Liberal Pulpit. He also served as secretary of Thomas D. West’s American Anti-Accident Association which pioneered the movement for workplace safety, promoted the idea of a “safe and sane” Fourth of July, and lobbied to reduce the number of saloons located near manufacturing establishments.

On Palm Sunday 1909, Harris announced to a surprised and saddened congregation that he would resign his pastorate. The necessity of a drier clime following weeks abed with pneumonia that January was given as the reason. While it was hoped he would return after a few months convalescence, he soon accepted a position at the First Universalist Church of Colorado Springs. He quickly won over the congregation who accepted him as their permanent pastor only a week into a probationary assignment. Nonetheless, within six months Harris had resigned to take up a position in San Diego; ill health (his wife’s this time) was again cited.

His new church was not Universalist, but rather the Unitarian Society of San Diego. He was a successful pastor there, overseeing construction of a new church building in 1910 and speedily paying off the debt. Controversy, though, was not far ahead. On February 21, 1912, Rev. Harris announced his withdrawal from the two-month old pact of the Ministerial Association of San Diego not to marry divorced persons. A Reverend Crabtree from the Central Christian Church joined Harris in his protest. Besides being inclined toward a Freethinking view of marriage, Harris’ opinion on this matter was no doubt colored by the fact that he himself had divorced and remarried in 1908. This at a time when divorce among the clergy was very rare and, except for the party wronged by an adulterer, remarriage of divorced persons was forbidden by most denominations.

Shortly thereafter, he transferred to First Unitarian Church of Oklahoma City. Harris was warmly recommended by the Evangelical Association of San Diego; they described his ministry as “of such a character as to dispel prejudice and make for Christian unity” and called him a “leading force and a helpful presence in all works of human service in this city.” The San Diego Daily Union likewise commented: “Since Harris’ incumbency the church has prospered, taking its place among the foremost religious organizations of the city. His departure will be exceedingly regretted by members of the clergy throughout the city as well as by hundreds of warm friends outside the church who respect him for his ability, his democratic manner and friendly attitude toward all classes.” Nonetheless, these repeated instances of minor controversy, followed by a hasty but much lamented departure—sometimes accompanied by a claim of ill health—leads one to wonder about the bruised feelings and parish dissension the newspaper announcements perhaps omitted.

In Oklahoma City, Harris began writing scenarios and screenplays for motion pictures. The first screenplay accepted was the Trail of the Lost Chord, which was produced by the American Film Manufacturing Co. (the “Flying A Studios”) of Santa Barbara, California. In all, from 1913 to 1917, Harris is credited with writing or collaborating on the story or screenplay for over two hundred motion pictures. He strove to write for literary or classic productions with a moral, even allegorical, character. Indeed he considered his dramatic efforts as complementing his ministerial work. The “motion picture drama,” Harris said was “the best possible way to present a moral or religious lesson.” When the Oklahoma Legislature debated closing the movie houses on Sundays, in contrast to the ministers who agitated for the bill, Harris prominently opposed such a ban. Among his arguments were: “The work of the church today is in harmony with the theatre and all amusements; what is bad on Sunday is just as bad any other day, and what is fit on a week-day is fit on a Sunday. The church can stand without legislative support, if it cannot the divineness of its mission is doubtful.”

With over two hundred films to his credit and eventually employed as a staff writer and editor for the Gaumont and Fox studios, it would have been difficult to keep to his stated goal of writing only the morally uplifting while avoiding “a comedy or sensational melodrama.” While his film The Spender was chosen by the National Unitarian Temperance Society to demonstrate the evils of drink, the title of The Vivisectionist certainly suggests a more lurid tale. A Daughter of the Gods, starring the Australian swimming sensation and exemplar of beauty Annette Kellerman with its spectacular sets and cast of nearly 20,000 extras filmed on location in Jamaica, was the first feature with a million dollar budget as well as the first to contain a nude scene. Despite tastefully employing Kellerman’s long tresses of hair, the nudity outraged the likes of Rev. L.K. Peacock, an acolyte of Billy Sunday, and an old adversary from Harris’ days in Sharpsville.

By 1916, Harris had moved to New York City, having left the ministry and devoted himself to screenwriting full-time. (This was no sudden decision, for back in 1908 he wrote: “It has been a conviction of mine for months that I can be of larger service to humanity if I could cast off my ‘Rev.’ and get out among the ‘people’ and tell them the glories of life and obligations of living.”) By March 1917, however, he was back in the pulpit at the Church of Our Father in Newburgh, N.Y. The next year he moved to the Washington Heights Universalist Church in Manhattan. For once, he found a church at which to settle, staying there twenty years. The congregation disbanded on his retirement in 1938.

During the time of the United States’ entry into the First World War, a patriotic ardor arose in Harris which would continue for the rest of his life. The Little American, a 1917 Cecil B. DeMille film starring Mary Pickford that Harris co-wrote, propagandized against the barbarism of German troops and U-boats. Three years later, Harris founded the United States Junior Naval Guards, and later the United States Junior Aviation Corps. These organizations appear to have been something of a cross between the Boy Scouts and R.O.T.C. They were frequent participants in parades and patriotic events in the New York City area until their disbandment in 1937. Prior to the beginning of a second world war, Harris spoke as a strong opponent of unqualified pacifism. In response to an anti-war petition circulated by a group of clergymen in 1935, Harris said he was “disgusted” with them for what he termed “a display of near treason.”

After 1917, no film credits for Harris are found, though he maintained an interest in the field. In 1921 he incorporated the All-Story Films Corp. (which appears to have had no actual productions) and was advertising classes and private instruction in writing screenplays.

Around this time, Harris started a summer camp for boys in the Adirondacks, Camp Wamego—with Harris and his wife Muriel serving as directors. Though advertised for a time as “The Boys’ Country Club of the Adirondacks,” he spoke of its aims as deepening a boy’s character mainly through associating with others and connecting with nature. Nearly the entire camp burned in February 1939, with Harris escaping through a window. He cut ties when the camp reopened, with (apparently unfulfilled) plans to start another summer camp at Lake Luzerne, N.Y. for deserving boys who could not afford the cost of the new Wamego.

In 1937, as a last enthusiasm, Harris founded the Animals Friends’ League, later the Dog Lovers League of America, in response to recent bans of dogs by New York landlords as well as overzealous municipal “dog-menace” laws. This was perhaps not a new concern, for back during his Crown Point, N.Y. pastorate at the turn of the century, Harris edited and published Humane Christian Culture a magazine dedicated to the humane treatment of animals.

After his retirement, Harris’ characteristic restlessness reawakened. He moved from Manhattan to Camp Wamego in 1938, to Sharpsville in 1940, then he spent a winter in Georgia before finally returning to New York City.

Clarence J. Harris’ remarkable life came to a close at New York City in 1941. He was survived by his wife Muriel Seibel Harris, two sons and three daughters.

Sources

There is a ministerial file for Harris at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. He is briefly mentioned in books including: The Winchester Centennial, 1803-1903 (1903); J. G. White, A Twentieth Century History of Mercer County Pennsylvania (1909); Theodore Thomas Frankenberg, Spectacular Career of Billy Sunday, Famous Baseball Evangelist (1913); John M. Comstock, The Congregational Churches of Vermont and their Ministry, 1762-1914 (1915); and Ernest A. Dench, Motion Picture Education (1917). A short article by Harris, “A Reply to ‘The Preachers and the People'” appears in The Humanitarian Review (October 1908) while his work in San Diego is covered in Unitarian Word & Work (1908).

Newspaper article can be found in the Atlanta Constitution; Brooklyn Daily Eagle; Christian Leader; Colorado Springs Gazette; Daily Oklahoman; New York City Evening Telegram; Greenville Pennsylvania Evening Record; Kingston Daily Freeman; Gloversville, New York Leader Republican; New York Times; San Jose Mercury; Sharon Telegraph; Springfield Daily Republican; Sunday Oregonian; and the Worcester Spy. Harris’ motion picture work is documented on-line in The Internet Movie Database (IMDb.com) and the American Film Institute (AFI.com) Catalog of Feature Films. There is an obituary in the New York Times, November 29, 1941.

Article by Ralph C. Mehler

Posted April 19, 2011