Edward Everett Hale (April 3, 1822-June 10, 1909) was one of the most prominent American Unitarian ministers of the last half of the nineteenth century. He was also a popular journalist, editor, and author. His short story, “The Man Without A Country,” is an American masterpiece. An active social and charitable reformer, he founded the Lend a Hand Society to help people needing financial assistance.

Hale was born in Boston, Massachusetts; his parents, whose families were involved with the founding of the town and the American Republic, were Sarah Preston (Everett) and Nathan Hale. On his father’s side he was the grandnephew of Nathan Hale, the Revolutionary War hero, and on his mother’s the nephew of Edward Everett, orator and president of Harvard College.

In 1813 his father became the owner and editor of the Boston Daily Advertiser, the community’s first every day newspaper. His father and his extensive private library had a great influence on Edward. Years later Hale stated that he found it “hard to think of any real knowledge of any sort which I have ever had, on any subject, of which I did not trace the ‘origins’ to him.”

When he was just four weeks old, his parents brought him to their prestigious Brattle Street Church to be christened by John Gorham Palfrey. This was his introduction to Unitarianism. His education began when he was two at Miss Whitney’s private school. When he was nine, he was admitted to the Boston Latin School where he studied for the next four years. His engaging book, A New England Boyhood (1893), describes his childhood and early years with warm delight. One of his youthful activities was working in his father’s newspaper and book business. The knowledge he gained was especially useful to him later as a writer and editor.

When Hale was thirteen he graduated from Boston Latin School and entered Harvard College. He found its curriculum dull but the library, with its fifty thousand volumes, proved to be one of the great joys of attending Harvard. Nevertheless, he was generally disappointed with his Harvard education; declaring when he graduated, “I was sternly old-school; thought Mr. Emerson half crazy; disliked abolition; doubted as to total abstinence, and in general, followed the advice of my Cambridge teachers, who were from President down to janitor, all a hundred years behind their time.” Still, when he graduated in 1839 with the A.B. degree; he did so second in his class, as a member of Phi Beta Kappa, and as the commencement poet. It marked, he declared, the end of “boyhood” and the start of “manhood.”

Although he wanted to be a minister as long as he could remember, his first adult job was as a teacher of Latin at his old Boston school where he stayed for the next two years. Then he worked for his father as a journalist writing articles on local politics plus travel pieces based on trips throughout New England and New York. He also began to try his hand at fiction and had written his first story, “Jemmy’s Journey,” as early as autumn 1839. The first to be published, however, “A Tale of a Salamander,” was in 1842 in The Boston Miscellany, which was edited by his brother Nathan.

This period, 1839-46, also found him training for the ministry. Instead of going to a theological school, he elected to be privately tutored by the two ministers he knew most intimately, Samuel Kirkland Lothrop, his minister at Brattle Street Church, and John Gorham Palfrey, its former minister, and now Professor of Biblical Literature and Dean of the Harvard Divinity School. If both were conservative Unitarians, both were also highly respected within the movement.

On October 24, 1842 he appeared before the Boston Association of Ministers, and after sermonizing for them, they voted: “That Mr. Edward E. Hale having presented to this Association satisfactory testimonials of his qualifications for the Christian ministry, receive our approbation to preach the Gospel, together with our recommendation to the Churches of our denomination, and our sincere prayer and hope for his future success and usefulness.”

As he did not yet feel ready for a parish, he spent the next four years preaching whenever he had the opportunity. His first engagement was at Newark, New Jersey, and the next at Henry Whitney Bellow’s First Congregational Church of New York City. Soon he was preaching in a variety of locations, sometimes for just a Sunday but at other times for several weeks, as at Northampton, Massachusetts and Washington, DC.

As his ministerial skills improved so did his writing ability. More importantly, his mind and intellect matured, and the subjects that he wrote about broadened to include historical and moral matters. Such a publication was his March 1845 pamphlet, “A Tract for the Day: How to Conquer Texas, Before Texas Conquers Us,” which was issued as Congress debated annexing Texas as a slave state. Hale argued that it should be admitted but as a free state. He was now an abolitionist.

Hale was ordained and installed as minister of the Church of the Unity in Worcester, Massachusetts on April 29, 1845. Individuals from the city’s First Unitarian Church had founded it the previous year. According to his son and biographer, Hale thought of a church “as one of the active social factors in American Life, working by whatever personal or institutional means suggested themselves, toward the up-building of the community in which it existed.” That view remained constant throughout his life. As did his religious faith, which he defined succinctly as “Our Father who art.” Later he expanded this, declaring, “I can tell you in very few words what I believe. I believe that God is here now, and that I am one of his children whom he dearly loves . . . the truth is, that what a man needs is to live as much as he can . . . For faith, the soul needs to pray simply to God, ‘Father—help me,’ [and] that is quite enough and to act bravely on what faith it has already.”

He soon settled into preparing sermons and being attentive to parish duties. Yet he found time to make frequent trips to Boston for family visits and to absorb the city’s intellectual atmosphere. As he became comfortable in his new role, he enlarged his ministry. When he was asked to serve on the school board, he refused, choosing instead to be one of the overseers of the poor. Such “practical philanthropy,” along with his own private generosity to those in need, became a hallmark of his ministry. Through conversations with Ralph Waldo Emerson, he began to better understand Transcendentalism and came to appreciate Emerson’s writings.

Hale edited

The Rosary of Illustrations of the Bible (1848), a collection of poems and essays on biblical topics by authors such as Jones Very, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder, James Martineau, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and William Henry Furness. His next book, Margaret Percival in America (1850), celebrated the religious freedom of America and the diversity of beliefs it supported. It was a response to the English book Margaret Percival (1847) by Elizabeth Missing Sewell a book for young people that privileged High Church Anglican and Catholic beliefs.

A growing respect for Hale’s ability led Boston’s First Church to ask him to be their minister, which he refused, and to the American Unitarian Association inviting him to deliver an address at their 25th anniversary celebration in 1850.

A year later he met Emily Baldwin Perkins, granddaughter of the Calvinist preacher Lyman Beecher and niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They courted, married on October 15, 1852, and had nine children.

When congress opened the Kansas and Nebraska territories for settlement in 1854, it inflamed debate about free and slave states. Hale responded by urging non-slave holders to emigrate west to keep these future states “free.” To achieve this goal, he helped form the New England Emigrant Aid Company, and wrote Kanzas and Nebraska (1854), a comprehensive study of the area’s native tribes, history, and geography.

In spring 1856 the South Congregational Church in Boston, Massachusetts asked him to be their minister. “The chief and sufficient reason for accepting the call,” his son wrote, “was that the South Congregational Church was an active, vigorous church in a large and influential city, and opened a much greater opportunity than did Worcester for just the work he had been coming to see was his work.” So that summer he returned to his beloved Boston, and in October was installed as their minister, a position he was to hold for the next 43 years.

In 1858 Hale formed a society called “The Christianity Unity.” Its purpose was for mutual friendship and assistance, which was accomplished “by strict temperance and purity of life, and by fulfilling the duties of good citizens and friendly neighbors.” For years he was its president, saw it as part of his regular church duties, and as a companion to the work done by the Benevolent Fraternity of Churches in Boston.

Hale was a regular contributor to Unitarian journals, such as The Christian Inquirer and The Christian Register. He also began to write editorials, essays, and book reviews—sometimes anonymously—for newspapers. Along with Frederic Henry Hedge he edited The Christian Examiner, 1857-61.

When he returned home after briefly visiting England, Holland, Germany, Italy, and France, he published an account of the experience, Ninety Days’ Worth of Europe (1861). This was also when he wrote for the Atlantic Monthly his humorous/serious short story, “My Double, and How he Undid Me.” It told of a minister tired of the boring aspects of ministry, who decided to hire a lookalike to tend to those duties. It immediately caught the public’s fancy and brought him his first national attention.

As his congregation increased to become one of Boston’s leading parishes and because many families now lived in a different location, a larger edifice in a more convenient area was built just before the Civil War. During the war Hale worked with the United States Sanitary Commission and its president Henry Whitney Bellows to improve the dire health and medical situation facing wounded soldiers and those living in army camps. Throughout the war Hale urged military enlistment. To promote patriotism, he composed his most famous short story, “The Man Without a Country.”

It was published in the Atlantic Monthly for December 1863, and told the tale of the traitor Philip Nolan who, when convicted, declared that he never wanted to hear again of the United States. As a result his punishment was imprisonment at sea for the rest of his life. The story’s call for patriotism during the Civil War influenced Hale’s generation, and those that followed, and made him a national figure. Before, he wrote, “I was only known in Boston as an energetic minister of an active church; then the war came along and brought me into public life, and I have never got back into simple parish life again.”

Within the landscape of Unitarian theology, Hale was, with Henry Whitney Bellows, James Freeman Clarke, and Frederic Henry Hedge, a “Broad Church” leader. They were, as the Unitarian scholar Conrad Wright wrote, “emphatically Christian” and “committed to the Church.” As such they believed that all of the denomination’s divisions, the conservatives, evangelicals, and radicals, could be welded into a more harmonious union than presently existed.

Henry Whitney Bellows became the leader of the movement to accomplish this, and Hale was his “second in command.” Their efforts resulted in the holding of a convention in New York City in April 1865, which led to the formation of the National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches. Its basic purpose was to strengthen the work of the denomination through better church representation, increased financial efforts, and stronger planning. The creation and accomplishments of the National Conference proved to be one of the most significant organizational developments to take place within the American Unitarian movement

The decade of the 1870s found Hale—who had amazing stamina and energy—extremely busy preaching, writing essays, and publishing stories. His sermons dealt with themes linked to prayer, God, the Bible, charity work and the duties of city churches. His fiction books included How To Do It (1871), His Level Best (1872), and In His Name (1873), titles which today are no longer enjoyed by the reading public, as is the situation with most of the 18 novels he penned.

Hale started, with his own money and with help from his longtime friend and benefactor, textile manufacturer William B. Weeden, plus a loan from the America Unitarian Association (AUA), the magazine Old and New (1870-75). Although he was its editor, and wrote part of its contents, its mixture of literature, politics, and theology, never found an audience, and Old and New was finally absorbed by Scribner’s Monthly.

During the last two decades of the nineteenth-century Hale—a Life member of the AUA—was involved in countless denominational duties. When the Universalists celebrated their centennial at Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1870 he spoke as the Unitarian representative, and every time—and there were many—the AUA revised its By-Laws he served on the committees drafting changes. Indeed, throughout his career he was engaged in the ongoing work of many Unitarian endeavors: the Unitarian Sunday School Association, the Young People’s Religious Union, the Ministerial Union, and the Unitarian Pension Society. In addition, he regularly took part in the ordination and installation services of contemporaries. In 1879 Harvard recognized these many accomplishments by awarding him an honorary A.M. and S.T.D. In 1891 he visited California giving lectures and preaching in Unitarian churches.

In the early 1880s Harriet E. Freeman became one of his volunteer secretaries. Born in Boston in 1847, her family had been connected with his church since 1861, and in 1871 she had become the treasurer of its ladies’ charities organization. That task fitted well with her work at the women’s committee of the Massachusetts Indian Society and the Boston Fatherless and Widows Society. Hattie, as she was called, and Hale shared the same approach to life, and over their years together worked for common causes. As a result their relationship grew close, and finally loving and most intimate.

When they were away from each other, they stayed in touch by writing letters. The 3,000 of them which have survived, dating basically from 1882 until his death, were kept private by being written “partly” in code. So while the majority of each letter is in longhand, the more intimate passages were written in Towndrow’s shorthand. They reveal both the love that existed between them, and how Harriet assisted Hale with writing sermons, essays, and books. So he, Harriet, and others, kept their passionate and intellectual union concealed for decades, and it was only at the start of the twenty-first century that it was revealed. Hale was fortunate to be surrounded by loyal and loving family and friends; they kept the relationship secret, helping him avoid any hint of public scandal which might have revealed the inconsistencies between his beliefs and his actions.

Hale’s second most popular and influential story, “Ten Times Ten is One” had been published in 1870 in Old and New. Its hero Harry Wadsworth and his motto to “Lend a Hand” immediately resulted in the formation worldwide of hundreds of “Lend-a-Hand Clubs,” “Look-up Legions,” and “Harry Wadsworth Clubs.” At first Hale’s church office handled the correspondence generated by the clubs but eventually the Ten Times One Corporation was formed becoming in 1898 the non-sectarian Lend A Hand Society. Its headquarters was in Boston and Hale served as president until his death. Working in collaboration with other charities it still offered programs and services in 2014, even though all the clubs had long ago ceased to function.

No matter what else he was doing during these years, Hale was constantly writing or dictating, often to Hattie, an essay or story, usually first for a magazine and only then gathered into a book. But his work was not limited to his own publications. In 1881 he was encouraging fellow travel writer Helen Hunt Jackson to read the early Spanish language histories of California. In his essay, “The Queen of California,” Hale had traced the etymology of the state name to a Spanish romance, Sergas of Esplandian (1510). He edited James Freeman Clarke: autobiography, diary, and correspondence (1891). He also contributed several essays to the 4-volume Memorial History of Boston (1880-83), and the 8-volume Narrative and Critical History of America (1884-89), both edited by Justin Winsor, librarian with the Boston Public and the Harvard University Libraries. With his son Edward E. Hale, Jr. he published the collected letters of Benjamin Franklin in two volumes titled, Franklin In France (1886-88).

During this period he was also editorially involved with two other publications, Lend A Hand: A Record of Progress and Journal of Organized Charity, which was absorbed by Charities, and his last, a far less ambitious newsletter, Lend A Hand Record. Active as a lecturer for the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle he also wrote articles for their magazine, The Chautauquan. By now Hale’s political thinking was not only local but worldwide. Reflective of this was his support through articles in the Peace Crusade, published weekly in 1899 by the Lend a Hand Society, of the work of The Hague Peace Conference of that year, and its creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

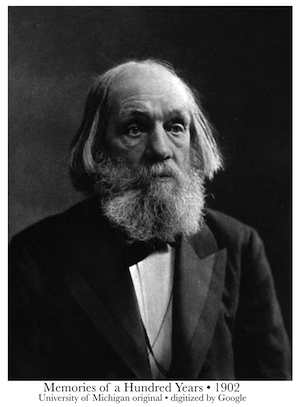

Edward Everett Hale retired as minister of the South Congregational Church in 1899. Grateful for his services, the congregation made him Minister Emeritus, and often invited him to preach. Retirement found him active in the work of many organizations such as the Massachusetts Historical Society, the American Philosophical Society, and the Unitarian Historical Society, which he had helped establish in 1901. As always he continued to write, producing books like Memories of a Hundred Years (1902), How to Live (1900), and with Harriet Freeman, a popular history of New England, Tarry at Home Travels (1905).

Many honors now came his way. Dartmouth College awarded him an honorary LL.D. in 1901, as did Williams College in 1904. The newly formed American Academy of Arts and Letters elected him to membership in 1908. Soon after he retired he was unanimously appointed Chaplain of the U. S. Senate, a post he held from 1903 until his death. When Congress was in session, Hale and his ailing wife lived in Washington, which he enjoyed because it enabled him to mingle with many influential people. These included President Theodore Roosevelt, who he had earlier worked with to establish a settlement house while he was chaplain to Harvard undergraduates, and President William Howard Taft, an influential Unitarian lay leader.

Hale died on June 10, 1909. The day before he had attended the annual meeting of the Lend a Hand Society. It was an appropriate final activity for, as The Boston Transcript declared, next to “unity among the religious denominations” that Society “was probably the nearest to his heart of his many interests.” His funeral service was held the following Sunday afternoon in the South Congregational Church. To accommodate the many people wishing to pay their respects a second service was held at the same time in Park Street Church where clergy of different faiths paid him tribute. He was buried in nearby Forest Hills Cemetery.

In 1913 a life-size bronze statue of Hale was erected in the Boston Public Garden. Funded by public donations, it was created by sculptor Bela Lyon Pratt. It shows an elderly Hale, hat in one hand, cane in the other, strolling through the Boston Public Garden. A fitting tribute for an optimist who taught people to, “Look up and not down. Look forward and not back. Look out and not in. Lend a hand.”

Sources

The Edward Everett Hale Papers (1750-1909) in Manuscripts and Special Collections at New York State Library in Albany, New York has 31 boxes of diaries, correspondence, journals, scrapbooks, church records, and printed works. The manuscript division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., holds Edward Everett Hale items in the Hale Family Papers (1698-1916). This include correspondence, journal, sermons, lectures, and numerous Hale-Freeman letters. Additional items can be found in the Hale Family Papers (1787-1988) at the Neilson Library, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. The Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, in Cambridge, Massachusetts holds several Hale collections including papers, (1814-1908), sermons (1846-1906), Antioch College correspondence, and his AUA ministerial file. Also see the Papers of Harriet Freeman (1860-1922) at Andover Harvard Library for Edward E. Hale photographs, journals, articles, and news clippings. Additional Hale items can be found at Harvard University, the University of Rochester, Yale University, and Wichita State University. Consult the ArchiveGrid at WorldCat.org for more information.

The records of the Church of the Unity (1844-1920) are at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts; those for the South Congregational Church (1828-1929) and the Lend A Hand Society (1843-1982) are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. A collection of Hale’s Works, although incomplete, was issued by Little, Brown in 10 volumes in 1898-1901, and “A Checklist of the Writings of Edward Everett Hale,” compiled by Jean Holloway, is available in the Bulletin of Bibliography, v. 21. For information on Hale and the National Conference see “Henry W. Bellows and the Organization of the National Conference,” in Conrad Wright, The Liberal Christians: Essays on American Unitarian History (1970), and for a thoughtful; contemporary assessment of Hale’s chief work see The Los Angeles Review of Books, March 24, 2013, “No Land’s Man: Edward Everett Hale’s ‘The Man Without a Country’ Turns 150” by Alexander Zaitchik.

Full length biographies include Edward E. Hale, Jr., The Life and Letters of Edward Everett Hale (1917); Jean Holloway, Edward Everett Hale, a Biography (1956); John R. Adams, Edward Everett Hale (1977); and Sara Day, Coded Letters, Concealed Love, The Larger Lives of Harriet Freeman and Edward Everett Hale (2014). An excellent overview of Hale’s Unitarian religious involvements along with an extended examination of his family life and extra marital relationship can be found in “Harriet E. Freeman and the Larger Life of Edward Everett Hale” by Sara Day, The Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2008). Older biographical works include; Unitarian Yearbook (1909); Abigail Clark, “The Christian Register (1916); Samuel Atkins Eliot, Heralds of a Liberal Faith (1952); David Robinson,The Unitarians and the Universalists (1985); Mark Harris, Historical Dictionary [The A to Z] of Unitarian Universalism (2004); and American National Biography (2014). Obituaries—there are many—include those in the Boston Evening Transcript, June 10, 1909; New York Times June 11, 1909; The Christian Register, June 17, 1909, and Harper’s Weekly, June 19, 1909.

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted October 28, 2014