Edvard Grieg (June 15, 1843-September 4, 1907), considered Norway’s greatest composer, was the first to create an internationally celebrated body of musical works inspired by the folk-heritage and culture of Norway. Although most of his compositions were solo songs and short pieces for the piano, he contributed a few enduring Romantic-era classics to the orchestral and chamber repertoires. In his later folk music-based works he inspired the song and dance collecting of Béla Bartók and was a forerunner of twentieth-century harmony. Like Bartók, he developed unorthodox religious opinions which he identified as Unitarian.

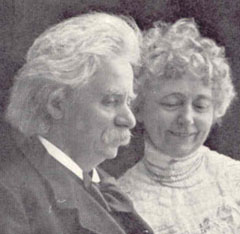

Nina Hagerup Grieg (1845-1935), a Danish-Norwegian Unitarian, was a concert singer and the inspiration for her husband Edvard Grieg’s substantial body of songs. She earned a reputation as an unrivaled interpreter of his vocal works. Her unique style penetrated the poetry and heightened the drama of the words. Composer Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky later wrote of her, “I have never met a better-informed or more highly cultivated woman.”

Edvard was the fourth of five children born in Bergen, Norway to Alexander Grieg, a North Sea merchant, and Gesine Judith Hagerup, a concert pianist, piano teacher, composer, and playwright. His father’s grandfather (their name was originally spelled “Greig” and pronounced “Gregg”) had come from Aberdeenshire in Scotland in the 18th century. For four generations Griegs, including Edvard’s father and brother, held the post of British consul in Bergen. Although both of Alexander’s sons, John and Edvard, studied music as children, he hoped that they would join the family business. John, who became a proficient cellist, did go to work for his father. Edvard, on the other hand, early declared that he wanted to be a Lutheran pastor. He later wrote, “To be permitted to preach or speak to a listening multitude seemed to me to be something great.”

Beginning when Edward was six, Gesine taught her son to play the piano. He wrote his first composition for piano, “Variations on a German Melody,” at about 12. In 1858 the celebrated Norwegian violin virtuoso, Ole Bull, convinced the Griegs to send their son to the Leipzig Conservatory in Germany. There, 1858-62, he studied piano and composition under, among others, Ernst F. Wenzel, Ignaz Moscheles, and Carl Reineke. His studies were interrupted in 1860 by an attack of pleurisy. Although he recovered and resumed his studies he lost the use of one lung and his health remained delicate throughout the remainder of his life.

Traveling to Leipzig, Grieg visited his relations in Denmark and met his first cousin Nina, daughter of his uncle Herman Hagerup and the celebrated Danish actress Adelina Werligh. Nina Hagerup was born in Haukeland, near Bergen, and moved with her family to Denmark when she was eight. She studied singing under Carl Helsted. Although, because of an illness during her youth, her voice had lost much of its power, she retained and enhanced her gift of vocal interpretation. Edvard got to know Nina much better in 1863 when he was studying music with Niels Gade and other Scandinavian composers in Copenhagen. He later claimed that all of his songs were written for Nina and that she was their “only true interpreter.” Despite opposition from both of their families, Edvard and Nina became engaged in 1864. That same year, he set poetry of Hans Christian Andersen to music, including his most famous song, “Jeg elsker Dig” (I love you), a declaration of his passion for Nina.

In 1865, while on a vacation trip in North Zealand in Denmark, Grieg recorded in his diary his thoughts about God, nature, and the role of the artist: “Where does one sense God’s greatness more than in the roaring of the sea? In a moment one becomes, as it were, an impotent nothing who in gratitude dares only to call upon the Father whose omnipotence created his wonders! And how beautiful it is that he has endowed his creatures with powers by which they not only can enjoy [the world], but can even create works of art that are echoes of the feelings about God’s greatness which are planted in the human breast.”

While in Copenhagen Grieg met the young Norwegian composer Rikard Nordraak, composer of the Norwegian national anthem. His influence, together with that of Ole Bull, sparked Grieg’s interest in developing a Norwegian style of music, separate from the predominating German style of the time. In 1865 Grieg, with Nordraak and others, founded Euterpe, an organization to promote contemporary Scandinavian music. After his friend died of tuberculosis in 1866, Grieg wrote “Funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak.”

Nina and Edvard married in 1867 and settled in Christiania (later called Oslo), Norway. Their only child, a daughter, Alexandra, died at the age of one in 1869. Around the same time Nina had a miscarriage. They had both hoped for and expected a family full of children. “It is hard to watch the hope of one’s life lowered into the earth, and it took time and quiet to recover from the pain,” Edvard wrote after the funeral. “But thank God, if one has something to live for one does not easily fall apart; and art surely has—more than many other things—this soothing power that allays all sorrow!”

Finding such compensations were not as easy for Nina. Although she gave occasional concerts, she largely subordinated her career to that of her husband. She tried to live the life of a traditional housewife, but was not temperamentally suited to it. Grieg later admitted that he did not realize until it was too late how much he had restricted his wife’s opportunities to have an international singing career. “I did not understand at the time how important her interpretations really were. For me it was only natural that she should sing so beautifully, so tellingly—from a full heart and from the innermost depths of the soul.”

In Christiania Grieg conducted the Philharmonic Society, organized concerts featuring works by Norwegian composers, and taught at the short-lived Norwegian Academy of Music, 1867-69. Because of a testimonial letter and invitation from Franz Liszt, the Norwegian government granted Grieg funds to travel to Rome in 1870. There Liszt played Grieg’s newly-composed Piano Concerto, op. 16 at sight, he advised the younger composer, “Hold to your course. Let me tell you, you have the talent for it, and—don’t get scared off!” Grieg treated this advice as “a sacred mandate.”

During the same period Grieg discovered Ludvig Mathias Lindeman’s collection of Norwegian folk music. From these he arranged his Norwegian Folksongs and Dances, op. 17. He conducted frequently the next few years in Norway and Sweden. (Norway was politically united to Sweden at that time.) He was elected to the Royal Music Academy in Stockholm in 1872. The following year Sweden’s newly-crowned King Oscar II made him, along with the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, Knight of St. Olav. Aided by the 1874 award of an annual government grant, Grieg was able to lessen his conducting duties.

In 1874 Ibsen asked Grieg to compose incidental music for his play Peer Gynt. The play and the music were first performed two years later. Grieg subsequently made two orchestral suites from the music which became his most celebrated works. While working on the score he half-jestingly wrote his closest friend Frants Beyer, “I have also written something for the scene in the hall of the Mountain King—something that I literally can’t stand to listen to because it absolutely reeks of cow pies, ultra-Norwegianness, and trollish self-sufficiency!”

Both Alexander and Gesine Grieg died in 1875. The loss of his mother and father led Grieg to doubt for the first time the Christian faith of his childhood and to wonder where he could turn for reassurance. He wrote, “No, you can have all the dogmas, but the belief in immortality I must have. Without that everything comes to nothing.” He channeled his grief into the composition of his most ambitious piano piece, the Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Folk-Tune, op. 24, written “with my life’s blood in days of sorrow and despair.”

Along with his loss of faith in Christian dogma, Grieg lost faith in the Lutheran ministry. They “strangle even the smallest attempt at goodness in us” and “they systematically suppress everything having to do with cultural life,” he wrote. He thought the church opposed his growth as a person and an artist. “Fighting against individuality is one of Christianity’s basic principles,” he wrote Beyer in 1883. “The clergymen will say that those who think that they develop are those of weak character, and those who stand where they stood as children are the strong ones, the ‘chosen.’ But what would this wretched and yet so divinely beautiful life on earth mean if it didn’t teach us something?” “It will take us hundreds of generations,” he complained, “to free us from the yoke of Christianity.”

Though he rejected organized Christianity Grieg retained his faith in its underlying spirit. Writing in 1880 he told a clergy friend that “even if I do not believe in the same literal details as you, I certainly do believe without reservation in the same great spirit of love” and that he wished “only for strength to struggle to possess just a little spark of that spirit of love which Christ radiated in his life.”

The anxiety of Grieg’s religious crisis remained in later years. “Whether one believes in God, Satan, Christ along with the Holy Ghost and the Virgin Mary, in Mohammad or in nothing, it is still the case,” he wrote in 1890, “that the mystery of death cannot be explained away.” In 1901 he said wistfully, “I could wish that I were a Buddhist, the better to understand and sympathize with the idea of annihilation.”

During the years 1875-83 the Griegs’ marriage underwent a series of crises. Both Edvard and Nina were strong-willed individuals and often quarreled. Both had to adjust to each other and to revise their expectations of the life that was possible for them together. Often depressed, Edvard felt neglected by Nina. Living in the mountainous Hardanger country of Western Norway, 1877-79, Nina felt cut off from the life she had enjoyed in cities.

In 1883 Edvard abandoned Nina for several months, leaving her in Norway with their friends, the Beyers, while he toured in Germany. Feeling constrained by all the circumstances of his life, including his marriage, he was tempted to go to Paris to join Leis Schjelderup, a young painter he had known in Bergen. He wrote home, “To come home now would be a disaster for me. It would be to go back to school, to tear myself out of my development—the fermentation that I can undergo only out here.”

Through the mediation of Frants Beyer the Griegs were reconciled. Nina joined Edvard in Germany in early 1884 and performed with her husband in a concert in Rome. Grieg began to accept that the difference between what he hoped to achieve as a composer and what he did in fact produce was not Nina’s fault, but was conditioned by personal frailty and other unavoidable constraints upon his life. He acknowledged that he had been “blind and weak,” and had chosen the wrong way to try to seek his freedom. Nina had to resign herself to her childless state. She wrote a friend at end of the crisis: “I have been through so immensely much recently, both loneliness and a lot of other evil things; but thank God I believe all the same that there is still much that is beautiful to live for, even if there is no one to carry on after one is gone.”

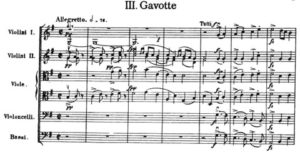

During these years of religious and personal crisis Grieg composed some of his most beautiful music. In 1878 he completed his String Quartet, op. 27. He composed one of his greatest songs, “Varen” (Spring) in 1880 and soon after arranged it for string orchestra as “The Last Spring.” Nina’s rendition of “Varen” later reduced Tchaikovsky to tears. In 1883 Grieg dedicated his Cello Sonata, op. 36 to his brother John. An 1884 commission from Bergen to celebrate the bicentennial of its native poet Ludvig Holberg led Grieg to compose The Holberg Suite, op. 40 (which he fashioned in both piano and orchestral versions.) The Griegs moved in 1885 to their own newly-built house, Troldhaugen, near Bergen.

The Griegs regularly wintered in Germany and elsewhere to the south of Norway. Nina preferred life on the road—giving concerts, away from housework, and being pampered in hotels. Edvard was her accompanist, even after he gave up soloing in public. Nina also appeared in concert playing the piano with her husband. She gave lessons to other singers. Edvard noted, “It is unbelievable what power she has to mesmerize her pupils.” When she sang in concert Nina dressed simply and was quite unlike a prima donna. “She penetrates right into one’s heart and soul,” wrote a reviewer. A contemporary singer wrote, “she created her own style . . . an animated dramatic recitative. She struck not only at the center of a poem’s feeling, but somehow plumbed the depths of individual words so they received a deeper, more distinctive color than one could get from mere reading.”

While visiting Leipzig in 1887 Grieg met Frederick Delius, a British student at the Conservatory, and encouraged him to become a composer. In 1888, while on his first concert trip to Great Britain, he met Delius’s father in London and presuaded him to let his son devote himself to a career in music. Delius later traveled in Norway with Grieg and was impressed by both the music of Grieg and by Norwegian folk music. His well-known composition, “On hearing the first cuckoo in spring,” is based on a theme from Grieg’s 1896 arrangement, Nineteen Norwegian Folk-tunes, op. 66.

Lawyer Charles Harding, vice-president of the Birmingham Festival, and his wife, Ada, members of the Unitarian Old Meeting Church in Birmingham, introduced Grieg to other Unitarians there, including members of the Kenrick family. Shortly before he died Grieg wrote, “During a visit to England in 1888 I was attracted to Unitarian views, and in the nineteen years that have passed since then I have held to them. All the sectarian forms of religion that I have been exposed to since have not succeeded in making any impression on me.”

Like most Unitarians of his time Grieg believed in God, the goodness of God, and the power of Jesus as an example—”Christ was filled by God as no one else known to me, living or dead, in the family of man.” He disbelieved in original sin. “Why should innocent people suffer for the sins of their forefathers?” he asked. “I think that the moral pain of the soul, which results from our bad deeds, as well as from the good we neglected to do, makes a Hell as effective as I can possibly imagine.”

In 1889 the Griegs were impressed by the ex-Anglican Stopford Brooke, who preached at Unitarian pulpits in London. “What a man! Nina says, and it is true,” Edvard wrote. “A big, splendid, sparkling personality full of fire and power. We talked about this and that: about Unitarianism and socialism . . . and I daresay he felt just as I do.” Grieg thought some Unitarians were “some of the noblest people I know.” Like them he believed in separation of church and state and in a tolerant attitude towards others—”for what we don’t know, we don’t know.”

Grieg’s religious attitude is reflected in the independence of musical thought that led him, as Liszt advised, to “hold to your course.” Broad in musical appreciation as well as in religious scope, he admired the music of composers, such as Brahms, whose styles were quite different from his own, and valued the musical inheritance from peasant culture, considering it not primitive, but advanced. He stood against conservatism in both religion and musical culture. Sickly from his youth, brooding on the passing of his baby daughter and of his parents, Grieg worked out his peace with death through his Unitarian faith, by connecting himself with the Norwegian people and their mountainous landscape, by putting his faith in nature as a whole, and through the life-affirming exuberance of his music.

Among the last songs Edvard wrote for Nina were the song-cycle, Haugtussa, op. 67, 1898. His last major work for orchestra was Symphonic Dances, op. 64, 1898. Late in life he continued to write piano works, including those arranged from folk tunes he collected himself. Among the more adventurous of these latter works were Slåtter, op. 72, based upon fiddle tunes from the Telemark region. This set of pieces influenced Béla Bartók who used them as teaching material and was inspired by them to research his own Hungarian folk music.

Grieg was honored by many awards, including honorary doctorates from Cambridge, 1894, and Oxford, 1906, and the Légion d’Honneur, 1896. In 1904 Grieg was visited at Bergen by Kaiser Wilhelm II, who talked to him about religion, among other topics. In 1905 he conducted for the coronation of King Haakon, monarch of the newly-independent Norway.

Because of the Dreyfus affair—in which a Jewish French military officer had been unjustly convicted of espionage and imprisoned—in 1899 Grieg canceled a tour to France and published his displeasure in print the Frankfurter Zeitung. As a result, in 1903, when he visited Paris he needed to travel with a police guard. His reputation amongst French musicians suffered. Claude Debussy, who was much influenced by Grieg’s chromatic impressionism, cruelly reviewed Grieg’s music as “pink bon-bons filled with snow.”

In his last year Grieg made another composer friend, the Australian-born Percy Grainger, who impressed him with his British folk-song arrangements and his playing of the Grieg concerto. The two planned to perform the piece at the Leeds Festival in England in 1907, but Grieg was hospitalized the day before he was scheduled to embark. He died the following morning. Two years before he died Grieg had written, “The great spirit—the world-soul that we call God—has breathed into each human being a desire to bow before him, and I, too, do that in full measure as I calmly entrust myself to His care when I shall depart this life.”

More than fifty thousand people witnessed Grieg’s funeral procession. “The Funeral March for Rikard Nordraak” (Grieg’s choice) and The Last Spring were played at graveside. His ashes were later moved to a cliff-side grotto overlooking the fjord at Troldhaugen.

Nina lived in Denmark for nearly thirty years after Edvard died. There she belonged to the Free Church Society (Unitarian) in Copenhagen, 1908-35. Although Nina had come to adopt many of her husband’s religious opinions, she did not share Edvard’s intense dislike of state churches. She hoped that one day the Danish Lutheran Church, more liberal than the Norwegian one, would become broad enough to include Unitarians. She donated to the Unitarian church building fund and organized and performed in concerts to raise money for an organ. Thorvald Kierkegaard, the Danish Unitarian minister, conducted her funeral ceremonies in Copenhagen. Her ashes are now united with her husband’s at Troldhaugen.

Although he was enormously popular during his lifetime, Edvard Grieg’s reputation declined during the early 20th century. In part this was because he was rated a master of small but not large musical forms. While many of Grieg’s smaller works—songs and lyric piano pieces—were masterpieces of their respective kinds, he rarely attempted works in more extended forms. His few longer works such as the Piano Concerto and the String Quartet, however, were quite as successful. But the enormous success of Peer Gynt and the concerto led to their over-exposure in the concert hall and subsequently on record. This slowed the rediscovery of some of his more adventurous works. A more comprehensive evaluation of his full oeuvre in the late 20th century, including his later piano pieces, has restored his reputation and revealed him as a harmonic pioneer. Among the composers he influenced, aside from those already mentioned, are Jean Sibelius, Carl Nielsen, Edward MacDowell, and Maurice Ravel. He has never lost importance in his homeland as Norway’s national composer.

Sources

Collections of Grieg’s letters and papers are at the Bergen Public Library in Bergen, Norway and in many other locations around the world. A list of these institutions can be found in the introduction to Edvard Grieg: Letters to Colleagues and Friends, edited by Finn Benestad and translated by William Halverson (2000). Other letters are in Lionel Carley, ed., Grieg and Delius: A Chronicle of Friendship in Letters (1933). A more comprehensive collection of the letters, in Norwegian is, Finn Benestad, ed., Edvard Grieg: Brev i utvalg 1862-1907 (1998). Other writings of Grieg, including his autobiographical pieces and journalistic articles on Richard Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen, Robert Schumann, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Giuseppi Verdi, and Antonin Dvorak are in Finn Benestad and William Halverson, Edvard Grieg: Diaries, Articles, Speeches (2001). The most comprehensive bibliography is Dan Fog, Kirsti Grinde, and Oyvind Norheim, Edvard Grieg, Werkverzeichnis (2001).

Grieg’s music has been published in Complete Works (1977-1995). Among pieces not mentioned above are a symphony (1864, an early work, on which he wrote “never to be performed”); concert overture, In Autumn (1866); Old Norwegian Melody with Variations (piano version 1891, orchestrated 1900); Two Melodies for string orchestra (1891); incidental music to Sigurd Jorsalfar (1872, including the famous “Homage March”); Bergliot (1871, a melodrama with dramatic speaker); Olav Trygvason, an unfinished opera (1873); Scenes from Folk-Life (1872); three violin sonatas (1865, 1867, and 1887); songs: “The First Meeting” (1873), “A Swan” (1876), The Mountain Thrall (1878), “From Monte Pincio” (1870), and Land-sighting (1872); a piano sonata (1865); and his ten sets of Lyric Pieces for piano (1867-1901). His piano music has been recorded in 14 volumes by Einar Steen-Noklenerg. Among classic performances of selections from the Lyric Pieces are those by Emil Gilels and Mikhail Pletnev. There is a three disc collection of Grieg’s Songs in Historic Performances (1888-1924) which includes a sample of Nina Grieg’s singing. The best modern recording of Grieg songs is performed by Anne Sofie von Otter. The a capella choral music has been recorded by the Oslo Philharmonic Chorus. The Piano Concerto and the celebrated works for string orchestra have been recorded too many times to mention. However, it should be noted that the complete orchestral music has been recorded on six CDs by the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra. There are also numerous recordings of the violin sonatas, the Cello Sonata, and the String Quartet.

The best biography of Grieg is Finn Benestad and Dag Scheldeup-Ebbe, Edvard Grieg: The Man and the Artist (1988). This is a translation into English by William H. Halverson and Leland B. Sateren of Edvard Grieg: mennesket og kunstneren (1980). Among other biographies are David Monrad-Johanson, Edvard Grieg, translated by Madge Robertson (1938); Henry T. Finck, Grieg and His Music (1929); and John Horton, Grieg (1974). Elisabeth Kyle, Song of the Waterfall: the Story of Edvard and Nina Grieg (1970) is a children’s book written in the style of a novel and geared toward the childhood and youth of its subjects. Much information on Grieg’s religion can be gleaned from primary sources, especially his letters. See also Knut A. Berg, Edvard Griegs livssyn: Unitar og prestehater (Oslo, Humanist 4 1993). The record of Nina Grieg’s connections with the Danish Unitarians is preserved by the Danish Unitarian Church in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Article by Peter Hughes

Posted November 4, 2004