Edward Williams (1747-1826) was one of the most influential and controversial figures Wales has produced. Raised Anglican, Williams as a young man enjoyed connections with liberal Anglican ministers. When Unitarianism later separated from the state-sponsored church, he associated himself with prominent English Unitarians and became a leading ally of Thomas Evans (Tomos Glyn Cothi), the first avowedly Unitarian minister preaching in Wales. Williams helped found the South Wales Unitarian Christian Society, for which he drafted the rules and arrangements in its 1803 governing document. Translating English Unitarian texts, he coined Welsh-language Unitarian religious vocabulary, and he wrote over 3000 Welsh-language Unitarian hymns.

Williams considered himself a Unitarian Christian but crossed conventional religious lines. In the 1790s he began performing a druidic liturgy celebrating solar equinoxes and solstices, but informed by Unitarianism and intended to promote it. Although not a pacifist, he admired Quaker adherence to anti-war principles during the Napoleonic Wars. Inspired by Quakers’ “priestless” worship, Williams in 1817 organized and regularly convoked a group of laypeople he called Bereans; imitating the Biblical group from whom they took their name (Acts 17:10), their purpose was to study Biblical texts, but from a Unitarian perspective. Williams’s focus on lay religious life and on the religious value of social activism sometimes put him at odds even with co-religionists. For example, he advocated abolishing the slave trade, even though his own brothers profited from it and abolition was not a popular cause in Wales. He exploited the renown of his later years to help those needing financial or medical assistance (he was an excellent herbalist) as well as victims of a justice system that, for example, condemned a young man to death for his theft of 25 shillings (the sentence was commuted). He helped his children establish themselves financially, but he died poor. In short, Williams used his literary talents in the service of his religion, while his religious views informed his sociopolitical opinions and actions. He was an activist both within and without his denomination.

Born and raised in the Vale of Glamorgan (his sobriquet ‘Morganwg’ is the Welsh name for this, the southernmost, region in Wales), Williams spoke English and (Glamorgan) Welsh natively, wrote poetry and corresponded in both languages, and avidly studied and promoted Welsh cultural achievements. From his father he learned freestone masonry, which he worked at most of his life; it was a traditional craft, taking its name from a characteristic of local oolitic stone, which can be worked ‘freely’ in any direction without splitting into layers. Williams literally dedicated an edifice for Welsh Unitarianism, carving Biblical verses (probably John 4:22 and I Timothy 2:5) for the first church constructed for Unitarian worship in Wales (Capel Cwm Cothi, built ca. 1792, and inscribed probably in 1796). In 1802, more controversially, he also carved inscriptions (from I Cor. 8:6) on two churches, at Pantydefaid and Capel-y-Groes, both established as Unitarian churches seceding from the (then Arian) mother church at Llwynrhydowen. Some of Williams’s architectural plans and drawings have survived, including those he drew up for a never-built Unitarian academy.

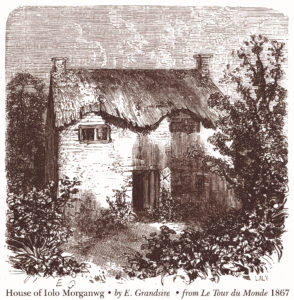

Born at Pennon (Llancarfan parish) Williams moved with his family (ca. 1754) to the village of Flemingston, to the house that became his lifelong home. Although he had little formal education, his mother, with social connections more genteel than her husband’s, provided such cultural advantages as parlor music and an introduction to English literature, including Shakespeare, Milton, Ovid (in English translation), and religious books, including the English Bible. Williams later recalled having taken special interest in religious literature and poetry. The family’s home language was English, but the young Williams participated in the nascent Welsh language revival in Glamorgan. He learned Welsh through friends, among whom were clergymen, poets, and lexicographers; several were known for their liberal views, and they became Williams’s mentors as he began to write poetry in Welsh, using both traditional Welsh forms and forms borrowed from English. His first published work appeared in a new (1770) Welsh-language magazine. One of the editors was Josiah Rees (1744 – 1804), a minister in the line of Rational Dissent, who later co-founded the South Wales Unitarian Christian Society. Williams’s correspondence with Rees is among the earliest extant records connecting Williams with Rational Dissent and its offspring Unitarianism.

In 1770 – 1771, a dispute involving Williams led to blows and legal action, and then, on a trip to North Wales, he collected financing for a publication that never appeared. Under a cloud, he left for London in 1773, seeking work as a mason and sponsorship for his poetry, and he stayed in southeast England until 1777. American events were then exacerbating tensions in English political and religious life. Theophilus Lindsey, deciding that he could no longer in good conscience lead his Anglican congregation, resigned his position and offered English Radical Dissent its first institutional space, using a reformed liturgy in services at Essex House (starting Sunday April 17, 1774). There is no evidence of religious unorthodoxy on Williams’s part during these London years, but his continued adherence to Anglican norms says nothing about his involvement in religious life outside them. Much later, Williams wrote that he had been among Lindsey’s original Essex House congregation. His claim is sometimes doubted, but if it is accurate, his definitive turn to Unitarianism in the 1790s was prepared much earlier, probably in his early adulthood in Glamorgan.

In England Williams worked as a stonemason but also as a poet and antiquarian. His writings of the time favor conciliation and peace with the American colonies, and show what would become an enduring interest in America. Williams resented English disdain for the Welsh and condescension toward him by the North Welshmen dominating the London Welsh intellectual scene. He also disliked London’s dirt and the bad air, which worsened his asthma. As a mason, he worked hard in poor conditions, his health suffered, and he became addicted to opium. Yet he was strong enough to walk long distances all over Wales and southern England; his traveling was largely a matter of work and business, but he also preferring going on foot to avoid abusing horses.

Returning to Glamorgan, Williams could not find work there and traveled to look for it in Cornwall and Devon (1780). He married (1781, Margaret Roberts) and tried various ways of supporting his family, for example by farming land his wife inherited, but he fell into debt and spent a year (1786-87) in debtors’ prison in Cardiff. There he wrote extensively on Welsh bardism and druidry.

Williams’s choice of theme is significant. Modern British druidry was then in full flower and tended to involve seeking the divine in individual experience of the natural world, and in that way was inherently opposed to religious hierarchy and obedience to authority. British poets placed “their” ancient druids (and bards, with whom the druids were often conflated) in a national tradition of liberty, as distinct from the authoritarianism of European continental states, and druids show up in several poems with names like “Liberty”, by James Thomson, or “Ode to Liberty”, by William Collins. The theme of liberty will have attracted the imprisoned Williams. At the same time, Williams’s contemporaries generally understood ancient druidry as a set of religious practices and beliefs; since nothing about ancient druids is known, however, no one could be quite sure what sort of religion to ascribe to them. In an effort to reconcile Britons to their supposed pre-Christian past, some antiquarians proposed that ancient British druids had been monotheists who smoothed the path for eventual conversion to Christianity, which in some accounts the druids themselves accepted. Since the druids were usually associated with mysterious rituals, the Puritans, hostile to liturgy, were generally unfriendly to druids, while some orthodox Christians discerned a druidic trinity. Williams’s druids were Unitarians. Finally, of course, Williams’s druids had to be Welsh; modern druidry of the time had already been assigned Keltic origins, re-interpreted as specifically Welsh after the appearance of the Welsh bard in Thomas Gray’s famous ode “The Bard” (published 1757), completed under the influence of the Welsh harpist John Parry. Gray’s ode helped inspire the Celtic Revival that in turn supported the renewed interest in Welsh language and culture in the Glamorgan of Williams’s youth. Although Williams’s work on bardism/druidry was not yet published, its political, religious, and national aspects would eventually generate some of Williams’s most important contributions to Welsh cultural life and the history of British Unitarianism.

Williams’s imprisonment was also productive in a more personal way: his son Taliesin (the family’s third child) was conceived in the Cardiff prison. When he was freed, Williams was thus a man in middle age, with a growing family he could scarcely support, and unheralded achievements as a Welsh-language poet and antiquarian. The decade culminated, however, in his greatest success up to that time, when he contributed to the publication of works of a major fourteenth-century Welsh poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym. Williams had worked with the manuscripts on which the edition was mainly based during his London sojourn, and, at the last minute, he also contributed some previously unknown poems, which the editors included as an addendum. Williams told the editors that the new texts were from Dafydd ap Gwilym manuscripts that he had just discovered, but really he had written them himself.

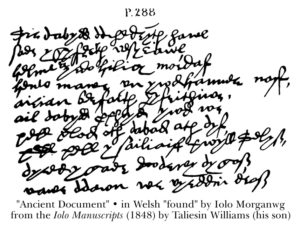

Literary falsifications were widespread in the eighteenth century. Williams’s most obvious predecessor was James Macpherson, a fellow Kelt and his nearly exact coeval, who created works he attributed to “Ossian”; Macpherson presented them as parts of an ancient Scottish epic translated from Gaelic. Williams was aware of Macpherson’s work when he began his own, and he also knew that Macpherson’s creation was suspect almost as soon as it was published. Williams outdid Macpherson, however, by presenting his “ancient” documents, not in translation, but in medieval Welsh (quite different from the modern language) that no one until the twentieth century could be sure was not genuine. Once modern scholarship caught up with him, unfortunately, Williams’s forgeries cast a shadow over all his work, and interest in it declined. Because of his key role in Welsh Unitarianism, Unitarian scholarship on Williams continued, but its immediate impact was limited until twenty-first century scholarship recovered Williams for a new audience.

Even in the nineteenth century, Williams’s Unitarian activism was relatively little known. It is remarkable, then, that Williams’s Unitarianism lies at the heart of the most popular national event in Wales, namely the great festivals called, in Welsh, eisteddfodau; specifically his Unitarianism informs their ceremonial highlight, called in Welsh the gorsedd (plural “gorseddau”), a solemn convocation that Williams created out of his own work on druidism. The druidic writings on which Williams based his ceremonies and teachings were just as inauthentic as his forged poetry. Probably most attendees at modern eisteddfodau are unaware that Williams was using his gorseddau to express and celebrate Unitarianism, which he regarded as the purest form of Christianity and therefore the natural heir to pre-Christian druidry. For their part, Unitarians seldom realize that their modern history is linked to Williams’s “reconstructed” Welsh druidry.

Although Williams used the words ‘druid’ and ‘druidism, he actually called his cult ‘bardism’. It was based on his notion of druidical religion, conceived of as monotheistic and theosophical, lacking a creed but defined by the bards’ (druids’) way of organizing and governing their society. Williams’s conflation of bardism and druidry may have been strategic, since it was probably his original intention not to graft druidry onto the bardic festivals (eisteddfodau) of his day, but to replace the festivals with spiritual convocations (gorseddau); the urgency of Williams’s activism in promoting his Unitarian gorseddau can be appreciated against the background of the competition he faced from religiously orthodox (and politically conservative) rivals, in particular David Thomas (Dafydd Ddu Eryri), a poet from North Wales who rightly mistrusted Williams’s “discoveries”. Finally, in 1819, the Welsh arm of the Church of England sought to inject itself into eisteddfodau in order to better naturalize the official church. Williams hijacked the project, conducting a pop-up gorsedd at the eisteddfod, and his gorseddau and the eisteddfodau have been linked ever since. His Unitarian vision for for druidism/bardism is perpetuated even in early twentieth-century Welsh Unitarian studies, notably D. Delta Evans’s 1906 book The Ancient Bards of Britain.

To appreciate what Williams was about in linking his fabricated druidry with his Unitarian convictions, it is helpful to situate Williams’s religion in the context of, on one hand, his career as a creator and promoter of Welsh culture and social justice and, on the other, the political and historical moment of the early 1790s, when his deep and public encounter with Unitarianism began.

As noted above, Williams’s renown in Welsh literature was enormously boosted by his (falsified) contributions to a major new edition of the work of Dafydd ap Gwilym; fatefully, however, the edition was completed on the eve of the French Revolution, its preface dated July 1, 1789. Early British response to the revolution was generally positive; Unitarian response approached delirium. Samuel Taylor Coleridge used gunpowder to burn the words “Liberty” and “Equality” into the lawns of Cambridge colleges, and Joseph Priestley looked forward to “the downfall of Church and State together” and the Second Coming of Christ (“It cannot, I think, be more than twenty years”); Williams apparently expected the world to end in 1796. Truth and Liberty became themes for Welsh poetry competitions, and Williams wrote pseudonymous political poems. He also began reading Enlightenment philosophy. He probably knew Richard Price, the radical minister and friend of Benjamin Franklin, as well as Price’s nephew George Cadogan Morgan; both were Unitarians from Bridgend, in Glamorgan. Williams not only read the works of Thomas Paine but also knew him personally. The list of subscribers to Williams’s poetry collection (published 1794) includes many politically significant liberals and radicals – Thomas Paine and Joseph Priestley among them – while Williams’s own views – against war, against official corruption, against tyranny and repression of all sorts – hardened and were increasingly strongly expressed.

To oversee publication of his poetry collection, Williams lived in London from 1791 to early 1795. Like his earlier London sojourn, this was in an era of political ferment, now inspired by French Revolutionary ideas and expanding military force. Britain and France were at war beginning in 1793, and there was an abortive French landing in Wales in 1797. Advocates, whether for Liberty, Equality and Fraternity or simply for peace, risked being accused of treason. Williams now enjoyed an expanded circle of radical acquaintances, and, thanks to his London bookseller, prominent religious dissidents. The bookseller was Joseph Johnson, known for distributing Unitarian literature, and for being imprisoned as a consequence. The relationship between Johnson and Williams arose out of not only their own mutual interest but also the situation of Unitarianism.

Throughout the eighteenth century, Unitarians had been disadvantaged by the 1688 Toleration Act (excluding Unitarians and Catholics from the category of officially tolerated dissent from Anglican doctrine) and the 1698 Blasphemy Act (which defined a three-year term of imprisonment for propagating anti-Trinitarian views). After Catholics finally obtained the benefit of the Catholic Relief Acts (1778-1793), a petition on behalf of Unitarians was likewise presented to Parliament in 1792. The petition failed, however, and the campaign supporting it exacerbated anti-Unitarian feeling; Unitarianism continued illegal in Britain until 1813. Wartime conditions made things worse, as patriotism became coterminous with official institutions. Unitarians were prosecuted in courts of law and they, their churches and even their homes were attacked by “king-and-country” mobs. The more insistent individuals among them were forced into emigration, jailed, or, like Thomas Fyshe Palmer, forcibly transported to Australia. When the persecuted Joseph Priestley left for America in 1794, Williams was present at his departure.

Yet Lindsey’s earlier establishment of an institutional home for Unitarianism had made a space for the religion to thrive and develop a clearer profile than when anti-Trinitarian Christians were scattered and without institutional support. That new maturity, and the existence of Unitarian institutions requiring legal protection, helped motivate the 1792 petition. For the earlier eighteenth century, it is not always possible even to identify who was, or was not, Unitarian in belief, and the general categories of anti-Trinitarianism and Rational Dissent encompass multiple views on the human or divine status of Jesus, including opinions more precisely described, in terms that refer to Christian theologians who held them, as Arminian, Arian, or Socinian – all labels used by Unitarians themselves at the time. From the early 1790s on, Unitarianism tended to define itself as theologically Socinian (denying the divine nature of Jesus and affirming his humanity). Moreover, and of special importance for the story of Unitarianism in Wales, Unitarians, having established their London beach head, were now interested in promoting their faith in provincial Britain and outside the fairly elite social classes where it had flourished. This new evangelism was spearheaded by a sophisticated new organization, the Unitarian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and the Practice of Virtue by the Distribution of Books, founded in 1791. Welsh skilled craftsmen like Williams were ideal adherents for the “new” Unitarianism of the 1790s, and he would have been a welcome member of the group around the bookseller Joseph Johnson. It was about the same time (1792) that the young Tomos Glyn Cothi (1764-1833) contacted the Unitarians with a request for financial assistance, which they provided, to build his first Unitarian church, housing the congregation he had formed and that had overflowed his father-in-law’s house. It was only in the mid-1790s, with the church newly built and Williams returned to Wales and holding frequent, but stealthily organized, druidic-Unitarian gorseddau there (one in 1795 attended by Tomos Glyn Cothi), that the two men are known to have met and become friends.

Williams initiated his gorseddau earlier, however; although details are sparse, the first one apparently took place on Primrose Hill, the highest hill in London, at the summer solstice in 1792, and a second one, in the same place, at the autumnal equinox. In all, there were three or four gorseddau in London in the years 1792-93. For at least parts of these gorseddau, the language used was English. Williams wanted to offer English people a glimpse of Welsh culture, and using English also showed that the gorseddau were public, conducted in broad daylight and illuminated by the sun. Williams’s bards were not to be a secret society, and the early inclusion of English suggests Williams’s promotion of an “ancient” Welsh ceremony was not based on a genealogical or ethnic national ideal but rather looked to the consecration of modern social and political institutions. Williams’s gorseddau, in other words, were religious ceremonies expressive of a modern, liberal viewpoint. They offered an opportunity for similarly minded people to meet and talk; they were rare, if not unique, in being public (and so protected against accusations of conspiracy) and yet offering radicals a chance to meet.

By 1794, official persecution of political radicals involved not only court proceedings and cruel penalties upon conviction, but also raids and arrests of booksellers and assaults by street mobs who forced bystanders to participate. Williams was hauled in and interrogated, by William Pitt, in May 1794. In the summer of 1795, newly published poems in hand, Williams went home to Wales. He became a storekeeper to maintain himself and his family but was unsuccessful; he expended energy twitting the government spies observing him, embarked on ill-advised ventures, and kept quarreling with people who might have helped him.

Williams’s religious views were by this time fully crystallized. In the eyes of orthodox Trinitarian Christians, Unitarianism is hardly a form of Christianity at all, but Williams considered himself Christian and wrote harshly about Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason (1794), in which Paine disavows all religions and churches (“My own church is my own mind”); Williams states that his fury at Paine’s disavowal of Christianity is all the greater because he had been inspired by Paine’s Common Sense (1776) and Rights of Man (1791-1792), and he calls Paine a “Judas”. Even by the 1770s, when Williams first went to London, Unitarianism in its Christian form was only one of several competing religions beginning to calve from the glacier of Trinitarian Christianity in Britain; contemporaneous with Theophilus Lindsey’s Essex Chapel, David Williams was preaching theism at his Margaret-Street Chapel. Theism, however, was often just a stop on the road to atheism. Unitarians, in contrast, insisted on their rootedness in scriptural authority—a genuinely Rational Dissent from what they considered corrupt text and inauthentic practices—and thereby their right to a place as Christians in Christian Britain. Edward Williams’s insistence on his hymns’ status as psalms, and his carving Biblical verses in stone on churches, thus expressed a particular view of British Unitarianism.

Most relevant to Williams’s religious life from 1795 to 1799 were the druidic gorseddau that he now held in Welsh and his friendship with Thomas Evans (Tomos Glyn Cothi). As the law forbade meetings of over fifty people, Williams was able to hold gorseddau only by moving them from one out-of-the-way place to another and inviting only a few trusted associates. By 1800 even this had become unsustainable, and then, in 1801, Evans was arrested. His trial and disproportionately harsh punishment were intended to break the back of liberal religious dissent in Wales, and it succeeded in demoralizing Evans himself and greatly setting back his Unitarian cause. The failure of Williams’s attempts to help, and Evans’s response to his imprisonment, also poisoned the relationship between the two men.

Williams, however, persisted in Unitarian activism, which he continued to connect with druidry. He helped create the South Wales Unitarian Christian Society, the chief purpose of which was to support Welsh Unitarianism, now heavily repressed, without having to communicate with London at every turn. In writing the society’s 1803 foundational document, Rheolau a Threfniadau Cymdeithas Dwyfundodiaid yn Neheubarth Cymru (Rules and Arrangements of the Unitarian Society in South Wales), he provided it with a motto from the gorsedd: Y Gwir yn Erbyn y Byd (The Truth against the World), accompanied by the “nod cyfrin” (mystic symbol), sometimes called the “awen” symbol; the same motto and symbol appear in the first edition of the hymnbook he wrote for Welsh Unitarian congregations.

Between 1802 and 1826 Williams wrote over 3000 Welsh-language Unitarian hymns – about one hymn every three days; the modern hymnbook Y Perlau Moliant Newydd (The New Pearls of Prayer, 1997) still includes 24 of his texts, more than any other hymnwriter’s from before the mid-twentieth century.

Williams thus enriched the institutional Unitarianism of Theophilus Lindsey with religious forms he claimed for ancient Wales. His appeal to Welsh national tradition and use of the Welsh language were not nostalgic, but a means of furthering a progressive social program among a long downtrodden people. Williams was no Welsh chauvinist, linguistically or culturally. He believed that anything could be said in any language, provided the words existed (hence his own abundant coinages for Unitarian church texts), and he imagined a future in which Native American languages might become ordinary means of written communication. His correspondence is mostly in English; had it not been, it could never have become the voluminous record that it is. Williams’s exploitation of Welsh in promoting Unitarianism illustrates his ability to meet his chosen audience on the ground where they stood, not a desire to drag the Welsh back into a mythical past.

Williams understood the advantages and dangers of his biculturalism. When he was a young stonemason, one of his brothers urged him to write in Welsh to better keep his trade secrets. In the 1790s, at a time when sympathetic English Unitarians considered Williams a harmless victim of persecution, his Welsh acquaintances found him cranky, evil-tempered, and potentially dangerous. The poems of his 1794 collection show his mastery of English verse norms but are framed in an aggressive commentary, in a voice English readers would have heard as that of a kind of stage Welshman. Similar stage managing is evident in Williams’s druidry, which he exploited, in the gorseddau, as a theater for Unitarianism. On one occasion (4 June 1794) Williams escaped a “king-and-country” crowd in London, by sinking into the role of a comic Welsh provincial without enough English to grasp what the crowd wanted of him. In a tight spot, Williams became a different person, and it saved him. His canny shape-shifting, however, has also made him hard to understand, and at times he has been wrongly identified with one or another persona.

Williams’s last years were relatively uneventful. In 1814, post-war, he was able to resume holding gorseddau, from 1819 onward part of the eisteddfodau. He continued translating English Unitarian texts (including a catechism, 1814) and writing hymns (first edition 1812) and other texts. He concerned himself with such organizational questions as the congregational roles of ministers and laypeople, as when he organized his Bereans (1817). Some of his dreams for his liberal religion remained unfulfilled – a Unitarian Society for the whole of Wales, a Unitarian College, a Welsh Unitarian magazine – and so did other ideas, such as a plea, voiced in letters to the mighty, to use their power to establish a congress of nations devoted to peacemaking and advancing toleration. And at the end he wrote a final affirmation of faith: “I look back on my past life, and on the principles which I have adopted, the doctrines which I have professed to believe, and still do firmly believe. I rejoice in them. They are my only comfort. All my hopes are founded immovably upon them, and in these sentiments I am not afraid to appear before the God in whom I have believed. I have not, I cannot change my opinions. I have for the greatest and the best part of my life lived in them. I die in them … [A]s I have long lived so will I die in the unshaken belief of the doctrines of Unitarian Christianity”.

Sources

The bulk of Edward Williams’s materials is in the archives of the National Library of Wales, which also holds unpublished dissertations. The most important of Williams’s correspondence has been published as The Correspondence of Iolo Morganwg (3 vols., 2007), produced under the general editorship of Professor Geraint H. Jenkins, Director of the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. The Centre has also published an authoritative series of seven interpretive volumes (2009 – 2012) under the general title Iolo Morganwg and the Romantic Tradition in Wales. The volumes refer extensively to related publications and to the archival material, and all the Welsh-language material produced in the project is provided with English-language translation.

Specialist work on Williams as a Unitarian is mostly in Welsh, including C.A. Charnell-White’s edition of Williams’s hymns (2009). An exception is D. Elwyn Davies’s groundbreaking article “Iolo Morganwg (1747-1826), bardism and Unitarianism”, in the Journal of Welsh religious history, vol. 6 (1998). The quotation from Williams’s affirmation of faith is taken from Jenkins’s 2005 article “‘Dyro Dduw dy nawdd’: Iolo Morganwg a’r mudiad Undodiaidd” [‘Grant O God Thy protection’: Iolo Morganwg and the Unitarian movement], in: Cof Cenedl XX, Geraint H. Jenkins, ed. Additional information and images can be found at iolomorganwg.wales.ac.uk/, welshchapels.org, and the National Museum Wales website.

Article by Emily Klenin

Posted September 15, 2018