Elizabeth Cleghorn Stevenson Gaskell (September 29, 1810-November 12, 1865), a lifelong Unitarian and the wife of an eminent Unitarian minister, was the author of a half-dozen novels, numerous short stories, and a biography of Charlotte Brontë. In her fiction she examined some of the the social issues of her time, particularly those associated with industrialization in mid-19th century England, the rise of the middle class, and the status of women. Although her books do not mention Unitarians explicitly, a number of her characters express general Unitarian values or are modeled on Unitarian originals and the plots of the books teach the lessons of her particular form of Unitarian theology.

Elizabeth was born in Chelsea, then a rural suburb on the western outskirts of London. Her parents, William and Elizabeth Stevenson, came from long lines of Dissenters: he from a radical branch, she from the more conservative Holland family. The Hollands were related to their fellow Unitarians, the Wedgwoods, and, through them, to the Darwins. Elizabeth’s uncle Peter Holland was a physician whose practice included the appentices at nearby Quarry Bank Mill, Styal, a model cotton mill run by the Unitarian Greg family.

Prior to his marriage William Stevenson had been a teacher at Manchester Academy and a preacher at Dob Lane Unitarian Chapel, Manchester. Rejecting the idea of paid ministry, he went to Scotland and apprenticed as a “scientific” farmer, 1797-1801. Unlike his friend James Cleghorn, Stevenson was not a success at farming. He was next a teacher and journalist in Edinburgh, 1801-04; then in London a civil servant until death, at the same time writing books and articles on agriculture, topography, and naval history.

Elizabeth Stevenson gave birth to eight children, of whom only the first, John, and the last, Elizabeth, survived. (John disappeared on a voyage to India around 1827.) She lived just thirteen months after the birth of her daughter. The motherless child was taken by her mother’s sister, Hannah Lumb, to the village of Knutsford, where she grew up in a household made up entirely of women. She called Aunt Lumb “my more than mother.” Lily, as she was called by family and friends, grew up in a warm and happy environment, an extended family of Unitarians in and around Knutsford. Her father remarried when she was four and raised another family in Chelsea. She visited this family but never felt close to them.

Elizabeth was educated, 1821-27, at a boarding school in Warwickshire, run by the Byerley sisters, great-nieces of Josiah Wedgwood. The school, which taught modern subjects in a comfortable, domestic atmosphere, attracted the daughters of a number of Unitarian families, including the niece of Harriet and James Martineau and the granddaughter of Joseph Priestley.

In 1829 Elizabeth went to Newcastle-upon-Tyne to stay with her distant relatives, the family of elderly William Turner (1761-1859), minister of the Hanover Square congregation. Turner was a friend of Joseph Priestley and Theophilus Lindsey, pioneers of British Unitarianism. Two years later she traveled to Manchester to visit Turner’s daughter Mary, who was married to John Gooch Robberds, minister at the Unitarian Cross Street Chapel. There Elizabeth met and, in 1832, married Robberds’s junior colleague at the chapel, William Gaskell.

William and Elizabeth had a happy marriage, based on shared interests in language and culture and a common optimistic faith. Elizabeth depended on her husband for stability, and William looked to her for her gaiety and liveliness. As Unitarians they did not believe that wives should be submissive to their husbands. Elizabeth certainly was not. William encouraged his wife to develop her own talents and to assert herself in promoting them. She did not find the path to her vocation an easy one. “I am sometimes coward enough to wish that we were back in the darkness where obedience was the only seen duty of women,” she confessed to friend Eliza “Tottie” Fox, then added, “Only even then I don’t believe William would ever have commanded me.”

During the first decade of her marriage Gaskell concentrated upon domestic life. She and William had four children who survived: Marianne, Margaret Emily (called Meta), Florence and Julia. When she could find an opportunity, Gaskell studied poetry, making notes for her husband’s classes. She also began to write poetry, notably “Sketches among the Poor, No. 1,” 1837, a joint project with William. Many of the short stories that she published much later, after she had become a well-known literary figure, were written or at least begun in odd moments during the 1830s and 1840s. Her gothic descriptive essay, “Clopton Hall,” was included in William Howitt’s Visits to Remarkable Places, 1840.

Gaskell avoided many of the traditional duties and roles of a minister’s wife. She nevertheless taught at the Unitarian charity Sunday School, visiting the homes of her pupils and thus learning about life among the poor. During the “hungry forties” she did relief work, visiting prisoners and helping to feed Manchester’s hungry.

In 1845 Willie, the only boy in the family, died of scarlet fever. William encouraged his wife to write a long story as a way to get through her grief. The resulting novel, Mary Barton, 1848, revealed the desperate poverty of the millworkers of Manchester. Gaskell’s sympathies were with the workers, the men, women and children who labored long hours under unhealthy conditions, living in great poverty, dying without hope or a chance at happiness. Rich mill owners, and her own middle class in general, were portrayed in a relatively more critical light. The book created a sensation, and sold well. Although the book was at first published anonymously, her identity quickly became known and she was forced to admit authorship.

Unitarian mill owner and friend, William Rathbone Greg, wrote a harsh review. “She has evidently lived much among the people she describes, made herself intimate at their firesides,” he wrote. But he felt that her sympathy for the working class “too exclusive and undiscriminating.” Like many other critics who found the work one-sided, Greg felt that Gaskell disregarded the efforts that employers made to respond to their workers’ suffering and to ameliorate their living conditions. Although many of the mill owners in William’s congregation were upset by Mary Barton, he never asked his wife to temper her criticisms or to apologize.

The much-loved novel, Cranford, 1853, did not involve Gaskell in controversy. Set in an idyllic village, not unlike Knutsford, whose upper class is made up exclusively of single women, most of them of “a certain age,” it is a comedy with subtle but serious themes—the transition from aristocratric to middle-class values, and the power of “feminine” virtues in the lives of both women and men. Cranford was Gaskell’s favorite among her books, and for many decades in the early twentieth century, her only remembered work.

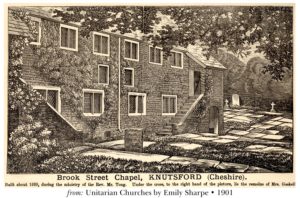

The most controversial of Gaskell’s novels, Ruth, 1853, tells of an unmarried woman who has a child. In it Gaskell pointed out the hypocrisy of a society which condones sexual adventures for men but condemns women for even a single slip. As the heroine was treated sympathetically by the author, the book was criticized severely. Some of her husband’s parishioners burned their copies. Ruth is graced by two good-hearted religious characters, Rev. Thurstan Benson and his sister Faith. They are identified as Dissenters, their values and beliefs a mixture of Unitarian values and Evangelical doctrine. The description of the Benson’s chapel in fictitious Eccleston is based upon the Unitarian chapel at Knutsford. The Eccleston parsonage was modeled after that of Rev. William Turner in Newcastle. Rev. Benson, of indeterminate theology, was also an indecisive character. Harriet Martineau labeled him a “nincompoop.”

North and South, 1855, which contrasts life in the rural south of England and among the upper class in London with conditions in the grimy industrial city of Manchester (called Milton-Northern in the novel), depicts the creation of a union and a violent strike. In her Manchester novels Gaskell demanded that the wealthy owners of the mills address the ills of the industrial age. She believed their Christian charity and good-heartedness could bring about the needed social change.

After reading Mary Barton, Charles Dickens had recruited Gaskell—whom he called “my dear Scheherezade”—to write short stories and articles for his magazine, Household Words. Most of her shorter works were published by Dickens in Household Words or All the Year Round. Many of the most effective of these pieces were tales of mystery or the supernatural. Cranford originated as a set of stories in Household Words. The cordial business relationship between Gaskell and Dickens deteriorated over disagreements about North and South. Gaskell worried that Dickens’s industrial novel Hard Times, which would be published first, might steal her thunder by treating the same themes she had. “I am not going to strike,” Dickens wrote, “so don’t be afraid of me.” Dickens wished to shorten the part in which the heroine’s father, an Anglican minister, doubts the trinity and other doctrines and decides to leave the church. He thought it “a difficult and dangerous subject.” Gaskell refused and afterwards resisted having the work shortened, retitled, or shaped for serialization. Dickens vented his frustration to a friend, “If I were Mr. Gaskell, O heaven how I should beat her!” The relationship, although somewhat cooled, nevertheless survived these hard negotiations.

Of the many political and literary figures she met Gaskell most liked and admired Charlotte Brontë. The two visited each other only twice, but kept in close touch through correspondence. After Charlotte’s death, her father, the Rev. Patrick Brontë, commissioned Gaskell to write her biography. Gaskell traveled to Haworth, where Charlotte had grown up, and to the school where Charlotte had studied and taught in Brussels and interviewed all who had known her. Unfortunately, Gaskell’s sympathy for the Brontës led her to accept uncritically some of their judgments of others. This led to threatened legal action. While Gaskell was in Italy, her husband and the publisher agreed to a settlement. She unhappily accepted the need for a public apology and a change in the next edition. One of the great biographies and a definitive study, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) reads much like a novel. It is a testimonial to a woman who managed, under severe handicaps, to balance obligations to her family with her imperative need to write. In her own life Gaskell was doing the same thing.

Gaskell’s health had been poor for some years; she had overdone at home, with entertaining and with anxiety about her daughters. Even her holidays on the continent were likely to be working ones, as she wrote short stories and travel articles to pay for them. As she began a new novel, a large advance allowed her to do something she had wanted to do for a long time, purchase a home in the south of England where she and William could live when he retired. On a visit to the new house in 1865, she collapsed and died, leaving her last and greatest novel, Wives and Daughters, 1865, not quite complete.

In Wives and Daughters Gaskell returned to her childhood roots, depicting people of various classes in and around a town like Knutsford. In its wit and social observation Wives and Daughters is a worthy successor to the novels of Jane Austen. Moreover Gaskell draws more widely and delves deeper into the social scale. She portrays a changing society, in which achievement will soon count for more than social position.

In 1969 critic Laurence Lerner called Wives and Daughters “the most underrated novel in English.” Since that time it and Gaskell’s Manchester novels have joined Cranford in the canon of English literature. Most of her works have become widely available. Gaskell is no longer regarded as a minor Victorian novelist, but is esteemed as peer of William Thackeray and surpassed as a writer only by George Eliot and Charles Dickens.

During her formative years Gaskell had been brought up amongst Unitarians of a Priestleyan cast. These included Turner, Robberds, and her husband. These “old school” Unitarians believed in a deterministic—called by Priestley “necessarian”—universe in which human error inevitably led to suffering, and suffering infallibly brought about reconciliation with God. The plots of her more serious novels conform to the necessarian pattern, sometimes apparently compromising the logic of her social messages. In a crucial scene in North and South she depicts three people, an Anglican, a Dissenter, and an “infidel,” kneeling together in mutual tolerance and reconciliation. According to scholar R. K. Webb, “Mrs. Gaskell’s Unitarianism is not to be found in her characters but in the dynamics of her narratives and in her comments upon her characters’ actions.”

Not wishing to be identified as a “Unitarian novelist” as this would severely limit her readership, Gaskell was careful not to tell her stories in explicitly Unitarian terms. In her personal letters, however, there are many clear expressions of her religious opinions and affinities. In a letter to her daughter Marianne she wrote, “one thing I am clear and sure about is this that Jesus Christ was not equal to His father.” Gaskell preferred devotional to doctrinal preaching. About doctrines, she wrote to Charles Eliot Norton, “I am more and more certain we can never be certain in this world.” She rejected “dogmatic hard Unitarianism, utilitarian to the backbone” and protested that she was not “(Unitarianly) orthodox!” See wrote a friend how she had tried to avoid seeing James Martineau, whom she did not like personally and whose “new school” Unitarian theology differed from her own.

Gaskell frequently attended Church (Anglican services) as well as Chapel. She enjoyed the spiritual feeling of the high church service. “I wish our Puritan ancestors had not left out so much that they might have kept in of the beautiful and impressive Church service,” she confided to Marianne. “But I always do feel as if the Litany—the beginning of it I mean,—and one or two other parts did so completely go against my belief that it would be wrong to deaden my sense of its serious error by hearing it too often.”

In Gaskell’s estimation, true Christianity was not to be found in organized denominations nor in liturgy nor in theology. She believed and acted on a religion of works, “the real earnest Christianity which seeks to do as much and as extensive good as it can.” Local action for change by those most intimately concerned, not government legislation, was her solution to social problems. Those who have should help those who have not. For her such charity began at or near home. She took her motto from Thomas Carlyle, “Do the duty that lies nearest to thee.” Unitarian rationalist feminist journalist Frances Power Cobbe, after reading a story by Gaskell, wrote, “it came to me that Love is greater than knowledge—that it is more beautiful to serve our brothers freely and tenderly, than to hive up learning with each studious year.”

Sources

The originals of Elizabeth Gaskell’s surviving correspondence are scattered in many collections throughout Britain and America. They have been gathered and issued in print, however, in J.A.V. Chapple and Arthur Pollard, editors, The Letters of Mrs Gaskell (1966). The Knutsford Edition, The Works of Mrs. Gaskell, edited by A.W. Ward (1906), 8 volumes, is the most complete edition of Gaskell’s works. It does not, however, include The Life of Charlotte Brontë. Gaskell’s novels and Charlotte Brontë are readily available in many editions, notably those issued by Penguin and Oxford University Press. Works not mentioned above include a set of serialized stories, My Lady Ludlow (1858); an historical novel, Sylvia’s Lovers (1863), and a short novel, Cousin Phillis (1864). Among Gaskell’s short stories are “The Poor Clare” (1856), “Lois the Witch” (1859), and “The Grey Woman” (1861). These and some others are collected in Laura Kranzler, editor, Gothic Tales (2000). The contemporary critical response to Gaskell has been compiled by Angus Easson in Elizabeth Gaskell: The Critical Heritage (1991).

Two valuable recent biographies of Gaskell are Winifred Gérin, Elizabeth Gaskell, a Biography (1976) and Jenny Uglow, Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories (1993). Coral Lansbury, Elizabeth Gaskell, the Novel of Social Crisis (1975) and Angus Easson, Elizabeth Gaskell (1979) are works of criticism with a strong biographical emphasis. Easson has a treatment of Gaskell’s Unitarian background and beliefs. More theologically sophisticated, however, is Robert K. Webb, “The Gaskells as Unitarians,” in Joanne Shattock, Dickens and Other Victorians (1988). There are shorter treatments of Gaskell in Concise Dictionary of British Literary Biography, Vol. 4: Victorian Writer, 1832-1890 and in Ruth Watts, Gender, Power and the Unitarians in England, 1760-1860 (1998). The fullest treatment of Gaskell’s husband is Barbara Brill, William Gaskell, 1805-1884 (1984). The story of her relationship with Charles Dickens is briefly told by Sally Ledger in Paul Schlicke, editor, Oxford Reader’s Companion to Dickens (1999).

Article by Maryell Cleary and Peter Hughes

Posted September 14, 2002