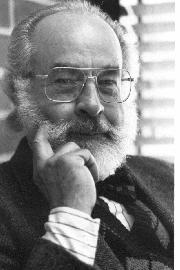

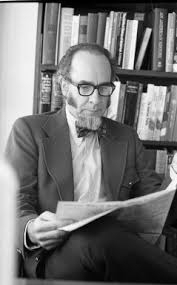

Ernest Cassara (June 5, 1925-April 10, 2015) was a Unitarian and a Universalist minister, a scholar of American Universalism, and a professor of history. He taught at Tufts University, Goddard College, Albert Schweitzer College, and then for twenty years at George Mason University. In addition to numerous scholarly articles, he published major works on Hosea Ballou, Universalism, and the Enlightenment in America.

He was born into a Sicilian American Roman Catholic immigrant family living in Boston’s West End. His father, Gaetano Cassara designed and made men’s clothing, and his mother, Amelia worked at home raising their seven children. The family soon moved to nearby Everett, Massachusetts where Ernest was educated in the public schools. During these years, he earned spending money working as a store and factory clerk, a helper on tar trucks, and as a drug store “soda jerk.”

While sports never interested him, music did, and he took singing, piano, and later organ lessons. In High School, he was President of the Gilbert and Sullivan Club and regularly performed in its productions. His flair for the “dramatic” led him to act in various school theatrical productions including having a leading role in the Senior Class play. Theater, opera, and classical concerts were a deeply rewarding passion throughout his life. According to his granddaughter, “He could hum an entire symphony in the car on the way to the symphony!” He also had a contagious sense of humor. He enjoyed telling stories, had a talent for it, and while doing so—before coming to the punch line—could never refrain from laughing.

Cassara was in high school during the Second World War. After graduation in 1944, he volunteered for the armed forces, but was rejected; he’d had rheumatic fever when he was 13. His family expected him to follow the lead of his brothers and become a hairdresser, but he ignored their wishes and enrolled in Boston’s well-known Leland Powers School of Theatre & Radio from which he graduated with a radio diploma in 1945.

That summer he worked for a Manchester, New Hampshire radio station. For the next five years, he worked as a radio announcer and news editor, first in Worcester and then in Brockton, Massachusetts. From September 1949 until June 1952, he was also an Instructor in Radio Speech for the Extension Division of Emerson College in Boston.

While he had been brought up a Roman Catholic, his parents were never strict believers. When he became restless and questioning about theology—around age 17, his parents encouraged him to develop his own religious ideas, a process that took several years. Every morning the Worcester radio station where he worked featured inspirational remarks by a local religious leader. One day the remarks were given by Walter Donald Kring, minister of First Unitarian Church in Worcester, Massachusetts. Cassara, who had never heard of Unitarianism, asked Kring to explain the faith. “He answered,” Cassara wrote later, “that Unitarians got their name from the fact that they believed God was a unity, not a trinity. That Jesus was a great teacher, but not divine, and . . . . insisted on the use of reason in interpreting the Bible and religion generally, and had great faith in the ability of humanity to confront the problems of life.” That struck a welcoming chord and led Cassara to further explore Unitarianism.

He later recalled that “among other activities,” he participated in while working at the Brockton radio station, “I found the most interesting to be the courting of a particular colleague.” Her name was Beverly Benner. Born in Hanover, Massachusetts in 1922, she was the daughter of a Baptist minister, a 1947 graduate of Colby College, and one of the radio station’s news editors and broadcasters. The courtship led to marriage, which was performed by her father on February 7, 1949. Both were strong individuals and their marriage was one of equals. Their daughter Catherine observed, “They were a team—a pair. He was her lover. Her admirer. Her advocate. Her biggest fan.” And she was his. That year the Cassaras joined the Channing Unitarian Church in Rockland, Massachusetts, and Ernest became its choir director, a post he held until June 1952. The first of three children, their daughter Shirley was born in December 1949.

Another life changing event for Cassara was the offer—by an anonymous donor—of a full scholarship to attend Tufts University. It was an opportunity not to be declined, especially since he was now thinking about becoming a Unitarian minister. He had, he wrote later, “always been very much interested in religion. If this had not been so, I probably would never have thought enough to break with Catholicism. Also, there is great satisfaction gained in being able to help people over the rough spots of life. One feels that he is devoting his life to something worthwhile, that his influence may in some small measure, at least, make the world a better place in which to live.” Perhaps for him the chief virtue of being a Unitarian minister was, as he succinctly stated, “freedom of conscience.” His decision to enter the ministry was also connected to his admiration for his local minister, Clayton Brooks Hale.

Cassara began his studies at Tufts College in a degree program that combined liberal arts and religion. He was the first in his family to go to college. Tufts accepted his Leland Powers credits so he entered as a junior. The family continued to live in North Abington, and Beverly supported the family teaching school as a substitute.

Cassara selected English as his major, even though he was very much attracted to historical studies. His courses covered the literature of the Middle Ages, Shakespeare’s plays, the poets of the English Romantic movement, Victorian prose, and American literature. Of special interest to him was the thought of Ralph Waldo Emerson. He also crammed in several history courses as well as learning Greek so he could further his New Testament studies.

While his busy schedule limited his freedom for extra-curricular activities, he did serve as Vice-President, and then during 1952-53 as President of the Skinner Fellowship, a Tuft’s student group. By taking summer classes, he was able to earn his A. B. in June 1952 and two years later his B. D. His thesis for that degree, “Cotton Mather and the Possessed” reflected his growing interest in church history. Beverly, even though she had given birth in March to their second child, Catherine, also received a degree that June; hers was an M. Ed. from Bridgewater State Teachers College.

The American Unitarian Association (AUA) granted Cassara ministerial fellowship, and the First Parish in Billerica, just west of Boston, called him to be their minister. He was ordained and installed May 9, 1954. The ordination sermon was by his mentor Clayton Brooks Hale with several members of the Crane Theological School faculty taking part, especially the Reverend Alfred S. Cole who was largely responsible for interesting him in American Universalist thought.

When Cassara came to Billerica, 135 families were connected to the church, Sunday attendance was 20, and the church school had an enrollment of 45 youngsters who studied, but only in part, the curriculum produced by the American Unitarian Association. When he resigned in June 1958 it had 175 families, the Sunday congregation was 70, and the church school was 90. During his ministry, the congregation adopted the Unitarian Universalist Beacon Series curriculum, a Couples Club was formed, and adult education courses were introduced.

While at Billerica, Cassara developed a warm and rewarding relationship with one of the church’s leading members, A. Warren Stearns. Stearns was a longtime member of the Tufts faculty, served as Dean of the Medical School, and was a former Commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Correction. In addition to his parish duties, Cassara served as a Representative to Town Meeting, Director of the Bennett Public Library, participated in the Billerica Historical Society, and served as Secretary of the North Middlesex Conference of Liberal Churches.

Shortly after he graduated from Tufts and secured his church position, Cassara made the decision to go to Boston University to secure a Ph. D. in church history. He studied under two of its School of Theology’s ablest teachers, Professors Richard M. Cameron and Edwin Prince Booth. For his dissertation, he decided to write the biography of the most significant Universalist minister and thinker of the nineteenth century—Hosea Ballou. He credited the “original inspiration” for this decision to two close friends, Alfred Cole and Alan Seaburg.

The Universalist Church of America granted him dual ministerial fellowship in 1955 and that autumn Tufts hired him to teach church history in the Crane Theological School. Two years later, a few months after his son Nicholas was born, Boston University granted him a Ph. D. and Tufts promoted him to Assistant Professor of Church History. In 1958 when the theological school started its scholarly journal, The Crane Review, Cassara was its first editor. He also played a key role in the rejuvenation of the Universalist Historical Society by serving as its volunteer librarian and one of the editors of its journal.

In 1961, the year that the Universalists and Unitarians consolidated into the new Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), Cassara’s revised dissertation, Hosea Ballou The Challenge to Orthodoxy (1961) was published. Charles H. Lyttle, the eminent Unitarian historian at the Meadville Lombard Theological School, in his thoughtful review in Church History wrote that Cassara had produced “a well-documented and discriminating delineation of Ballou’s doctrines, from his early, spontaneous aversion to ‘hell fire for the non-elect’ through its maturation, by dint of the teachings of Caleb Rich, Petitpierre, Charles Chauncy and especially Ethan Allen in his Reason the Only Oracle of Man (1782).” In addition, Lyttle found Cassara’s book “spiced and dramatized by pungent anecdotes” making “Ballou’s robust, forthright, kindly, democratic personality and ministry . . . interesting reading—the notes as well as the text.” Lyttle concluded that the study was “a well-structured, admirably objective, irenic and probably definitive work.”

In addition to the Ballou biography, Cassara also wrote two articles for the Journal of Universalist History during this period; “The Effects of Darwinism on Universalist Belief, 1860-1900,” (1959) and “A True and Remarkable Account of the Life and Trance of George de Benneville” (1960-61). He penned two more articles on the pending Unitarian and Universalist consolidation; “The Task Ahead of Us: Liberal Religion’s Heritage and Goal,” for the Unitarian Register (1961), and “Fundamental Concepts of the Unitarian and Universalist Ministries: A Historical Perspective Prepared for Interim Committee # 5 of the Unitarian Universalist Association.”

In 1957 the Cassaras bought the 200-year old farmhouse on Patch Mountain in Greenwood, Maine that became their beloved summer home for many years. “Papa mowed,” daughter Catherine remembered, “and repaired the house, installed the gravity-fed plumbing, kept a big garden, went berry picking with us, but also went into his study every morning to work. And when there was not to be disturbed.”

Granted a sabbatical leave for 1962-63, the Cassaras spent the year in Cambridge, England, where he did post-doctoral studies. At the end of his stay, when the Director of Albert Schweitzer College in Churwalden, Switzerland died suddenly, Cassara, with the approval of Tufts, was appointed as Interim Director for 1963-64. The college had been founded in 1953 by the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF). Cassara and Albert Schweitzer College were drawn into controversy after Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated the President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Oswald had been accepted as a student at the college in 1959 but had never shown up on campus. When reporters questioned Cassara, he had nothing to share; the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had pirated the college’s Oswald file. Fifty years later, assassination theorists were still interpreting those pilfered files.

Once back at Tufts, Cassara realized that he wanted to teach general history rather than church history. Therefore, when an offer came in 1966 from Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont, to teach history and be its Dean, he accepted. Originally established in 1863 by Universalists as a secondary school, it was now an experimental and progressive college, which stressed “discussion” as its chief teaching method. Goddard emphasized adult continuing education and, since that was a growing interest of his wife Beverly, she accepted a position as Goddard’s Director of Adult Education. She also now had earned from Boston University her Ed. D. Cassara gave up his ministerial status once he started teaching history, but he never turned away from his active commitment to religious liberalism.

In 1970 Cassara was appointed Professor of History at George Mason University in Virginia. Then a part of the University of Virginia, with a student enrollment of 1,500, George Mason grew during the 20 years he taught there, into an independent university with 20,000 students. He served several years as Chair of the History Department, and designed the required class for history majors “Interpretations of History” which surveyed historiography from Herodotus to the present day. Beverly took a position as Professor of Adult Education with the Federal City College in Washington, D.C.

His Universalism in America: A Documentary History of a Liberal Faith was published in 1971. A careful selection of historic documents covering Universalism from 1741 to 1961, it was prepared at the request of the UUA for the 200th anniversary of the founding of American Universalism. It is a companion piece to the documentary history, Epic of Unitarianism (1957), by David B. Parke. Cassara also published “Reformer as Politician: Horace Mann and the Anti-Slavery Struggle in Congress, 1848-1853,” in the Journal of American Studies (1971) and “The Rehabilitation of Uncle Tom: Significant Themes in Mrs. Stowe’s Antislavery Novel,” in the College Language Association Journal (1973).

His next book was The Enlightenment in America (1975) which clearly grew out of his earlier studies of the emergence of religious liberalism in the eighteenth century. He viewed it as “a modest effort” to summarize the various facets that made up the Enlightenment in this country. Reviewers also saw it as a modest effort; one said it was a “. . . summary of familiar and not always up-to date knowledge,” while a second said it merely, “rearranged what is already known.” He followed this with the annotated bibliography, History of the United States of America: A Guide to Information Sources (1977).

The Cassaras were in Germany for the 1975-76 academic year, each had been awarded a Fulbright Fellowship, he to teach American History at the University of Munich, and she to lecture at the Pädagogische Hochschule in Berlin. While there he started researching the German American, Carl Schurz, with the idea of writing his life. Returning home, he examined the Schurz holdings at the Library of Congress. He never wrote the biography but he did republish Schurz’s life of Abraham Lincoln (1999) for which he wrote “Carl Schurz: from German Revolutionary to American Statesman.”

As George Mason grew, his teaching duties expanded, limiting his time for research and publication. He wrote no more books until retirement, but he did continue writing articles and book reviews including, “The Development of America’s Sense of Mission,” for The Apocalyptic Vision in America: Interdisciplinary Essays on Myth and Culture (1982) and “The Student as Detective: An Undergraduate Exercise in Historiographical Research,” for The History Teacher (1985). He also edited a new version of Hosea Ballou’s 1805 book, A Treatise on Atonement (1986).

Cassara continued his work with historical and civic organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union, American Society of Church History, American Association of University Professors, and American Historical Society. And, after a thirty-year hiatus, he started to play the piano again, usually to relax after a full day of teaching, but really “for the sheer enjoyment of music.”

The Cassaras retired in 1990, moving first to Bethel, Maine then to Cambridge, Massachusetts. Beverly wrote a number of books in retirement. He kept busy with occasional lecturing and preaching at Unitarian Universalist churches and for the Ethical Society of Boston. He also sent argumentative letters “to the editor” of various newspapers, and wrote two period mystery books starring Hosea Ballou.

Cassara contributed three entries for the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography (Hosea Ballou, Lucius Paige, and Thomas Whittemore) and wrote “John Murray and the Origins of Universalism in New England: A Commentary on Peter Hughes’s ‘Religion Without a Founder,’” (1999) for the Journal of Unitarian Universalist History. Along with a colleague from his Goddard days, Cassara founded and edited a liberal blog for several years, titled Harvard Square Commentary. One subject he often covered was justice and fairness for the Palestinians. He and Beverly had visited Palestine and Israel to better understand the situation.

Travel was a priority and the Cassaras did so well into their 80s. Some places they visited, often in connection with her ongoing international work for Adult Education, were Brazil and Egypt. When their daughter Catherine was married in Tunisia, they were there, and always when they could they visited Great Britain, especially London.

In 2003 Beverly Cassara was inducted into the International Adult and Continuing Education Hall of Fame. She also founded the Cambridge Senior Volunteer Clearing House. In 2010 Chicago’s Meadville Lombard Theological School honored his “faithful service of contributing significantly to the creation of better people, more learned works, and a nobler world,” with the degree of Doctor of Humane Letters, in absentia. He died on April 10, 2015 and a Memorial Service was held on May 30 at the First Parish in Cambridge, Unitarian Universalist. Beverly died on September 20, 2016.

Sources

The Andover-Harvard Theological Library at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts has Cassara’s personal papers and UUA Ministerial File. Additional materials can be found in Special Collections & Archives, George Mason University Library, Fairfax, Virginia. The papers of Beverly Benner Cassara are at the Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries, Syracuse, New York. For biographical data see: Catherine Cassara, “For Papa’s Service,” First Parish in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Unitarian Universalist, (May, 2015); Ernest Cassara, The Road to Unitarianism and Universalism; A Personal Journey (2002); “Ernest Cassara Ordained at First Parish Church,” The Billerica News (May 13, 1954); Richard A. Kellaway, “Ernest Cassara: A Tribute” (May 2015); John Reosti, “Cassara to call it quits after two decades,” in the George Mason University Broadside (1990); “Ernest Cassara: Carl Schurz, German-American Political Leader,” in The Mason Gazette (May 10, 1985); and Ernest Cassara, “Play It Again! Confessions of a Prodigal Pianist,” Forecast (May, 1980).

In addition to the books mentioned in the text above, Cassara wrote two period mysteries featuring Hosea Ballou and his dog Spot: Murder on Beacon Hill (1996) and Murder on Boston Common (1998). Other writings not mentioned in the text include “The Intellectual Background of the American Revolution,” Revue Internationale de Philosophie (1977); “The New World of John Murray,” in Charles A. Howe, Ed., “Not Hell, But Hope”: The John Murray Distinguished Lectures, 1987-1991 (1991); “Concurrence and Contention: George Mason at the Philadelphia Constitution Convention,” in To the Western Ocean: The Anne Miniver Reader (2008); and “John Murray and the Origins of Universalism in New England: A Commentary on Peter Hughes’s ‘Religion Without a Founder’,” The Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (1999).

For a history of Crane Theological School consult Russell E. Miller, “A History of Universalist Theological Education,” The Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1984); for another view on Hosea Ballou see Mark W. Harris, “Hosea Ballou’s ‘Treatise’ at 200” (2006), and for Lee Harvey Oswald and Albert Schweitzer College look at, but use with care, George Michael Evica, A Certain Arrogance: The Sacrificing of Lee Harvey Oswald and the Cold War Manipulation of Religious Groups by US Intelligence (2011). Further details on Albert Schweitzer College can be found in Wayne Arnason and Rebecca Scott, We Would Be One: A History of Unitarian Universalist Youth Movements (2005). Obituaries are in The Boston Globe, April 17, 2015, Tufts Magazine, Fall 2015; and The Cambridge Chronicle, April 25, 2015.

Beverly Cassara published three books; American Women: The Changing Image (1967), Adult Education in a Multicultural Society (1994), and Adult Education through World Collaboration (1995). The Boston Globe, September 28, 2016 has an obituary for Beverly Benner Cassara.

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted October 21, 2015