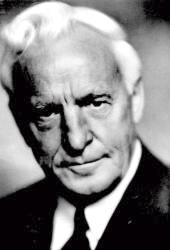

A. Eustace Haydon

A. Eustace Haydon (1880-1975), a pioneer in the study of world religions, was a leader of the Humanist movement. Born in Canada, he was ordained to the Baptist ministry and served a Baptist church in Dresden, Ontario 1903-04. After earning his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, Haydon was made Professor and Chair of the Department of Comparative Religion at the University’s Divinity School, a post he filled 1919-45.

Although he did not have Unitarian ministerial credentials, for five years (1918-23) Haydon commuted from Chicago to minister to the First Unitarian Society of Madison, Wisconsin. After retirement from the University, he served as Leader of the Chicago Ethical Society 1945-55. He was among the thirty-four authors and amenders of the 1933 Humanist Manifesto, first drafted by Roy Wood Sellars. Late in life Haydon also contributed to the 1973 Humanist Manifesto II. In 1956 he was recipient of the American Humanist Association’s Humanist of the Year award.

In his theoretical work Haydon described the “many and manifold” forms of religion as “the search for the good life,” a continuing quest for realization of the highest human ideals. “More needful than faith in God,” he wrote, “is faith that man can give love, justice, peace and all his beloved moral values embodiment in human relations.”

Haydon’s University lectures charmed and challenged his students. He wrote and spoke with a poetic quality. Among the many students drawn to his classes were future Unitarian ministers James Hart, Kenneth Patton, and Randall Hilton. Hilton, later Dean of Lincoln Center in Chicago and Secretary of the Western Unitarian Conference, recalled a seminar in which Haydon exercised his magic to open the minds of skeptical graduate students.

“We had been discussing for several days the role of meditation in various cultures. This particular day he came in, sat down, and said, ‘Today I am going to discuss prayer.’ The class laughed. He came in front of the table and said, ‘Let us pray.’ The laughter was even louder. He started talking. After the second phrase you could have heard a pin drop. At the conclusion he said ‘Amen.’ The class sat silent. Then he said, ‘That, gentlemen, is prayer.’

“Finally a cynic in the back row said, ‘No, Dr. Haydon, that is not prayer. It is hypnotism.’ To which Haydon replied, ‘Hypnotism, maybe, yes. What is hypnotism? The unification of a single mind around a single object. Prayer is the unification of the group mind around a single purpose.'”

Among humanists Haydon was a candidate for recognition as a latter day St. Francis. Outside the Divinity School he fed, nearly every day, a congregation of squirrels and pigeons. The squirrels climbed up his legs while pigeons perched on both shoulders. University of Chicago students called him “The Pigeon Man.”

Soon after his retirement Haydon’s approach to the study of world religions was superseded. The influence of his great heart and intellect survived in the ministry and work of his students.

Information on Haydon can be found at the University of Chicago, the First Unitarian Society in Madison, Wisconsin, and the Chicago Ethical Humanist Society. Obituaries appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times (April 2, 1975) and the Chicago Tribune (April 3, 1975). Haydon wrote The Quest of the Ages (1929), Man’s Search for the Good Life (1937), and Biography of the Gods (1941). He also edited Modern Trends in World-Religion (1934).

Article by Maryell Cleary

Posted January 27, 2014