Florence Ellen Kollock Crooker (Jan. 18, 1848 to April 21, 1925) was a Universalist minister and advocate of temperance and women’s suffrage. A capable organizer who combined intellect and passion in her work she was one of the first ministers to serve both Universalist and Unitarian congregations.

Florence was born in a log house, in the Wisconsin Territory (near Waukesha), to William and Ann Hunter Kollock. Florence was the fourth of seven children, the third daughter. Her mother came from Newcastle, England while her father’s family had emigrated from New Brunswick, Canada to the Detroit area in 1836. Four years later they moved to the Wisconsin frontier. Her great grandfather, a loyalist during the Revolutionary War, had emigrated from Lewes, Delaware to New Brunswick at the end of the war.

Her mother, raised in the Church of England, was spiritual and devout while her father, a Universalist, was more systematic and scholarly. Each respected the other’s beliefs. Her father read the Bible and enjoyed pitting his logical and rational views against his neighbors more dogmatic and superstitious beliefs. He read widely including Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune and Daniel and Mary Livermore’s New Covenant. Living on the frontier with few churches, the family often entertained itinerant ministers. Florence later recalled being inspired by Mrs. Griffith, a Methodist who was the community’s Sunday school superintendent.

After George, their last child was born in 1854 the Kollocks moved to Montrose, about 20 miles southwest of Madison, Wisconsin, so their children would be closer to the new state university. When Florence’s father learned that the University of Wisconsin president wanted to prevent the admission of women, he responded with a strongly worded letter. All of the children went to college. Mary and Harriet became doctors; Jennie and George dentists; Frank a lawyer; William a high school principal; and Florence a minister. Mary was the first woman to graduate from the University of Michigan (U of M) Medical School while Jennie was the first woman to enroll (second to graduate) in the U of M dental department.

For five years, Florence alternated between teaching public school and attending the University of Wisconsin (UW) in order to pay for tuition. At that time, male school teachers regularly received higher salaries. When she requested a raise, the school trustees replaced her with her younger brother William, at an increase of ten dollars a month. “That experience startled me;” she said, “when I realized what it all meant, I decided to advocate to the best of my ability that women receive equal wages for equal services.” Florence’s favorite UW teacher was classics professor William F. Allen. A member of the Free Religious Association, he often invited Jenkin Lloyd Jones to speak in Madison. It was Allen who called for the formation of the First Unitarian Society of Madison in 1879.

Before completing her course of study at Wisconsin, Florence determined that she wanted to be a Universalist minister. She wrote for advice to Mary Livermore, the editor of the New Covenant. Livermore encouraged her to enroll at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. Livermore assured her that, “women are admitted as freely as men, receive the same advantages, graduate with the same honors, and are ordained to the work of the ministry.” Florence enrolled in the three year divinity program where she studied under John S. Lee, Ebenezer Fisher, and Orello Cone. She received her divinity degree from St. Lawrence University in 1875; and an honorary master’s (MA) degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1883.

While a student at St. Lawrence University, Kollock preached at Universalist churches, including a three-month stint as pastor of Grace Church in Rochester, New York, in 1873. The following year she preached for three months in Rochester, Minnesota. After receiving her license in 1875, she accepted a position at Waverly, Iowa. She was ordained in Waverly the following year with Augusta Jane Chapin delivering the ordination sermon.

In 1878, Kollock was called by the Universalist congregation in Blue Island, Illinois, a railroad hub and brick-making town about 20 miles south of Chicago’s Loop. The Blue Island congregation, established in the 1840s, had its own church building. A short time later she started preaching on Sunday evenings at the “Unitarian Universalist Christian Union Society of Englewood.” This group, started in 1874, met in a Masonic Temple in Englewood, Illinois. Augusta Jane Chapin and Jabez T. Sunderland had previously shared pulpit duties there. Englewood, about ten-miles south of the Chicago Loop, was at the junction of the Rock Island and Michigan Southern Railroads. It was a new commuter suburb that had grown rapidly after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. Popular with professional and white collar workers it was the home of a new normal school and so many new churches it was called the “cradle of churches.”

In 1880, the Christian Union Society organized as the First Universalist Church of Englewood and built a small wood frame building at 63rd Street near Princeton Avenue. Kollock resigned from Blue Island and moved to Englewood. In addition to Unitarians and Universalists, the congregation attracted Independent, Swedenborgian, Quaker, Catholic and Jewish members. Unusual for the time, there were as many men as women in the pews, something that bothered some of Kollock’s female parishioners.

While vacationing in California in 1886, Kollock did some preaching in Pasadena under Amos Throop’s auspices. Caroline Soule, a Universalist, had held occasional services in Pasadena the year before. Under Kollock’s leadership the initial group of seven soon grew to 30 members and organized into the First Universalist Parish of Pasadena. Amos Throop was a wealthy Chicago businessman who had recently retired to California. A Universalist benefactor he supported mission efforts in California, served as mayor of Pasadena, and established what is now called the California Institute of Technology in 1891.

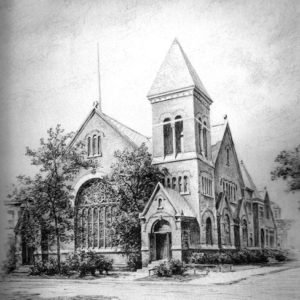

Membership at Englewood continued to grow. A larger building was finished in 1889 and the name was changed to the Stewart Avenue Universalist Church. Kollock presented Sunday sermons twice: There were evening services for young people, a women’s group, charitable club, literary club, and classes in world religions. The congregation grew to 400 parishioners and 300 Sunday school children. Kollock established the State Street Mission which helped poor families and children and she attracted prominent people to the church. Col. Francis W. Parker, America’s preeminent educator and principal of the Cook County Normal School taught a Sunday School Bible class there.

Kollock belonged to the Congress of Liberal Religious Societies, worked with Unity Magazine and the Western Unitarian Conference, and shared pulpits with the ministers of the Iowa Sisterhood. Kollock was close to Jenkin Lloyd Jones and liberal Chicago ministers, David Swing, H. W. Thomas, and Rabbi Hirsch. Preaching tolerance for the beliefs of others, she was considered too liberal by many Universalists. In an 1893 sermon, Kollock said, “We need to get out of this idea of the supernatural; we need to realize that it is all God’s natural law; we need to learn to read the Bible with this thought, that it is a record of the natural, that is, of the natural and spiritual in man. To do this we must get away from some of our teaching and preaching, must learn to be ourselves, to be individual, to reason out our own line of thought and belief.”

Kollock was also active in the suffrage movement. She testified before a congressional committee on suffrage in 1884 and was secretary of the Illinois State Suffrage Association, 1885. Julia Ward Howe, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony all spoke at her Englewood church. In 1890 it hosted the Illinois Equal Suffrage Convention. The word “obey” was not a part of Kollock’s wedding service.

In an 1890 sermon, Kollock supported the enforcement of Wisconsin’s Bennett Law that required the use of English in all public and private schools. At the time, many children of Catholic and Lutheran German emigrants were in bilingual classes at parochial schools. In another sermon she chided fellow Christian ministers for wasting time trying to close the World’s Fair on Sundays while “saloons, gambling dens, beer gardens, and like institutions are left undisturbed.”

It is not clear why Kollock resigned her ministry in 1892, one year before the World’s Fair. She had assisted with pre-fair preparations and her church was only a mile from the site of the 1893 fair which attracted 26 million people. One newspaper reported that she wanted to study social reforms in Europe and see the Holy Land while another reported that, “It was her intention to accompany an excavation party to Egypt in preparation for subsequent service as extension lecturer for the University of Chicago.” The congregation asked her to choose her own successor. She chose Rufus A. White, who would serve the congregation for the next 44 years.

Kollock spent her first year abroad visiting galleries and museums and touring historic sites in England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany. In London, she visited Toynbee Hall and the East End where she studied the work of the Salvation Army. As she was about to leave on the Egyptian expedition she received word from Amos Throop that she was needed in Pasadena, California. Kollock returned to the United States just in time to participate in the closing session of the World’s Congress of Representative Women, part of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

In Pasadena, E. L. Conger, who had ministered to the congregation since 1887 was ill. The church called Kollock to serve as his associate. After he resigned she served as full-time minister of the Pasadena church, 1893-95. Throop died in 1894. Kollock left the church in Pasadena, suddenly, in the spring of 1895 after learning her brother Frank had died.

After mourning the death of her brother, Kollock took a temporary assignment as General Organizer at the Shawmut Universalist Society (also known as the Every-Day Church) in Boston where she did social work and organized neighborhood activities. She raised funds for the Every-Day Church by speaking at New England churches. In Boston she spent more time with her old friends, Mary A. Livermore and Julia Ward Howe.

Kollock was active in denominational affairs serving on the Committee of Fellowship for the California State Universalist Convention and as president of the national Women’s Centenary Association (WCA). At the WCA, Kollock set up a fund that made interest-free loans to churches. She also was president of the Women’s Ministerial Conference that had been established by her friend, Julia Ward Howe and she served as president of the Association of Women Ministers.

Kollock married Joseph Henry Crooker in 1896 at the home of her sister in Freeport, Illinois. Her brother-in-law, John Hilton, a retired Universalist minister performed the ceremony. Joseph Crooker had been the Unitarian minister in Madison, Wisconsin, 1882-91, before moving to Helena, Montana, where he served, 1891-97. Joseph Crooker had a 22-year old son, Orin Edson Crooker, from a previous marriage. In 1898, Orin entered St. Lawrence University to study for the Universalist ministry.

In July 1898, Florence and Joseph Crooker were vacationing in Amherst, Massachusetts when they noticed that First Universalist Parish was closing. The Massachusetts Universalist Convention had withdrawn financial support. The Crookers contacted Samuel Atkins Eliot, the new secretary of the American Unitarian Association (AUA), and he arranged to purchase the Universalist meetinghouse. Eliot dispatched William A. Ballou to minister to the new congregation, which was renamed Unity Church.

Shortly thereafter, Joseph Crooker was called to the Unitarian church in Ann Arbor, Michigan where he replaced Jabez T. Sunderland who was leaving for India to visit the Khasi Hills Unitarians. Florence was appointed state missionary in Michigan for both the Unitarians and the Universalists.

In 1903, Florence and Joseph traveled to London where he addressed the British and Foreign Unitarian Association Convention in London and the triennial International Congress of Religious Liberals in Amsterdam. They also filled guest pulpits in England and Scotland.

In 1904, Florence was called to the ministry at St. Paul’s Church in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. Once again she helped revive a failing church using her preaching and managerial talents. Then in 1910 the board asked her to resign. According to her husband, this was the result of, “a sudden, thoughtless impulse instigated by one family whose only objection was their dislike of a woman preacher!” While Florence was at Jamaica Plain, Joseph had served in Roslindale, Massachussetts, three miles to the south, a position he kept until 1912.

Over the next ten years Florence and Joseph held interim positions with a number of congregations. He preached at the Unitarian Church in Redland, California while she worked with the Universalist congregation in Riverside, California, 1913; they provided religious education and leadership at Christ Church in Dorchester, Massachusetts, 1914-15; returned to Unity Church in Amherst, Massachusetts, 1917-18; assisted with “congregational repairs” at the Unitarian Church in Long Beach, California, 1918; substituted for the minister in Richmond, Virginia for three-months, 1919; preached at Highland Springs, Virginia, 1919; and served the First Parish in Carlisle, Massachusetts, 1920-21. In the spring of 1921 the Crookers were in Knoxville, Tennessee organizing a new society.

During this decade of temporary assignments they had more time for travel. They returned to England, 1914; visited Henry N. Couden in Washington, D.C., 1917; took six-months off to write in Oberlin, Ohio, 1917; and vacationed in Pasadena, California, 1919. In 1923 and 1924 they spent part of each winter in Berea, Kentucky, at Berea College.

In 1920, the Crookers moved to Lexington, Massachusetts while they worked together at First Parish Carlisle, about ten miles away. Florence and Joseph were disillusioned by the nation’s growing opposition to liberal ideas. They thought it would be difficult to find a publisher for their writings and that they would probably never make a difference anyway, so before leaving Lexington, they burned all their manuscripts and journals, while “still confident that God is in all and over all.”

Death

Florence died in Elgin, Illinois, in 1925. Orin Edson Crooker was the minister at Elgin’s First Universalist Society.

Sources

A detailed view of Florence Ellen Kollock Crooker’s life is found in the 14-part biography written by her husband, “The Romance of a Pioneer,” in The Christian Leader (1926). Her ministerial file is in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. A few clipping and a copy of “The Romance of a Pioneer” are in the Joseph Henry Crooker papers in the Oberlin College archives. The Beverly Unitarian Church (BUC) archive holds a number of relevant documents including: Eugenie F. Morgan’s scrapbook (abt. 1906); copies of the Universalist Messenger, Illinois Universalist Convention; The Messenger, People’s Liberal Church; and a collection of handwritten notes, letters, and drafts by Vincent B. Silliman for a sermon, The Present and the Days that Were: A Sermon Reviewing and Interpreting the History of More than Eighty Years of The Beverly Unitarian Church (1958).

Florence Ellen Kollock, “Woman in the Pulpit” in The World’s Congress of Representative Women, ed., May Wright Sewall (1894) can also be found in Standing Before Us: Unitarian Universalist Women and Social Reform, 1776 – 1936, ed. Dorothy May Emerson (2000). For information on the Congress of Liberal Religions and the Western Unitarian Conference see Cynthia Grant Tucker Prophetic Sisterhood: Liberal Women Ministers of the Frontier, 1880-1930 (1990); and Charles H. Lyttle, Freedom Moves West (1952). Documents about specific congregations that are useful include; Asa Mayo Bradley, “Pacific Coast Universalism” (1937); Claudia Elferdink, “This is The Ride You Came For” (2004); Joseph A. Leonard, History of Olmsted County Minnesota (1910); Norma Palmer, “Throop Memorial Church: Our First One Hundred Years” (1986); and Paul Sawyer, “A Brief History of Throop Church.”

Florence was adept at public relations. Stories, interviews, and photographs appear in many U.S. and foreign newspapers including; The Racine Argus (1879), the San Antonio Evening Light (1882), The Decatur Daily Dispatch (1889 & 1891), Chicago Daily Tribune (1890-92), Chicago Evening Post (1892), the New York Illustrated American (1891), Australia’s Brisbane Courier (1912); England’s Gentlewoman magazine (1892), the Englewood Southtown Suburbanite, The New York Times (1893), The Washington Post (1910 & 1914); and The Boston Post.

Article by Errol Magidson

Posted August 25, 2011