Henry Whitney Bellows (June 11, 1814-January 30, 1882) was minister of the First Congregational Church of New York City (now the Unitarian Church of All Souls), 1838-82. During the Civil War he was president of the United States Sanitary Commission. In the course of traveling for the Sanitary Commission he visited a great many Unitarian churches and recognized that Unitarian congregations’ traditionally informal modes of cooperation no longer met the needs of a fast-changing American society. Bellows was the Unitarian leader most responsible for the formation, in 1865, of the National Conference of Unitarian Churches, the first American Unitarian organization to have as members, not individuals but congregations committed to the growth and expansion of their movement. The National Conference, much more than the 19th-century American Unitarian Association (AUA), set the organizational pattern for the twentieth century AUA and the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Henry and his identical twin brother Edward were the sixth-and-seventh-born children of Unitarians Betsey Eames and John Bellows of Boston. John Bellows was a merchant active in city politics. Betsey died of consumption two years after the twins’ birth. A paternal Aunt, Louisa, helped care for the children. Three years later, John married Anne Hurd Langdon and had five more children. The twins were close as children. From 1824-28 both boys attended the Unitarian-run Round Hill School in Northampton, Massachusetts, one of whose principals was George Bancroft. Upon completing Round Hill, Edward went into business and Henry to Harvard College.

Bellows later wrote that he had first felt called to ministry at age 7. At 16, while at Harvard, he experienced a crisis of faith. Concerned that his spiritual devotion was not sufficiently vital, he engaged in diligent practice of prayer. The intensity of his religious crisis was increased by the death of his younger half-sister, Mary Anne Louisa.

After graduation from Harvard, Bellows taught languages and mathematics for a year at his brother John’s school for girls in Cooperstown, New York. He worked briefly as a tutor on a Louisiana plantation where he had his first direct encounter with the harsh realities of slavery. At Harvard Divinity School, 1834-37, he tutored in the mornings to pay his expenses, attended afternoon classes, and studied in the evenings. In his third year of Divinity School, Edward died in Michigan. Each year on their birthday Bellows mourned the death of his twin.

As a Divinity school student Bellows formed important relationships. For a time he and Orville Dewey, then assistant to William Ellery Channing at Boston’s Federal Street Church, lived in the same boarding house. He got to know Cyrus Augustus Bartol, his closest lifelong friend. Other friends were Samuel Osgood, Abiel Abbot Livermore, Charles Timothy Brooks and William Silsbee. Bellows respected the brilliant and radical Theodore Parker, in the class a year ahead of his, but the two were never intimately acquainted.

In 1837-38 Bellows preached for six months at the Unitarian church in Mobile, Alabama. Although offered the pulpit, he declined and returned north, concerned that, settling there, he might be seduced by the easy life made possible for the white upper class by the immoral institution of slavery. He subsequently became an anti-slavery moderate, urging emancipation by constitutional means. Having himself experienced the temptations of the South, he thought it both dangerous and wrong to label Southern slave-holders as evil.

William Ware had been the first-not notably successful-minister of the First Congregational Church (Unitarian) in New York City. William’s brother was the much loved and greatly respected Harvard Divinity School professor, Henry Ware, Jr. When William resigned, Henry Ware, Jr. and William Ellery Channing recommended Bellows as a possible successor. He candidated, in late 1838, for the ministry of the church. Called, he was ordained and installed as the church’s second minister on January 2, 1839. He served the church for 43 years, until his death.

Shortly after his ordination Bellows courted and wed Eliza Nevins Townsend, daughter of a wealthy church family. Eliza’s inheritance and Henry’s salary together provided ample resources for a comfortable life. Even so, because they felt their household, entertainments, etc. should match that of the New York elite, their finances were often tight. Henry possibly reflected on his own domestic situation when he later preached of “the strain of social emulation-which makes elegant fortresses of men’s homes.” Two of the Bellows’s five children, Russell Nevins Townsend Bellows and Anna Langdon Bellows, survived to adulthood. Russell entered the Unitarian ministry and served churches in Walpole, New Hampshire, and Harlem, New York. Eliza died in 1869; five years later Henry married 36 year-old Anna Huidekoper Peabody, Ephraim Peabody‘s daughter. They had three children.

Many children of distinguished Boston Unitarians had come to New York to make their fortunes and raise families. Their success helped to support developing Unitarian churches, and provided Bellows entry into New York society. Because of New York’s distance from Boston he developed his vision of the future role of liberal church away from the influence of his more parochial Eastern Massachusetts colleagues. Gregarious, genial, energetic, a fine orator and a distinguished public servant, he helped to integrate other Unitarians into society and civic affairs. As a member of the Sketch Club, and later the Century Club, Bellows met and mingled with the city’s leading men.

Bellows took his ministerial duties seriously and took great satisfaction in pastoral work. He valued education and worked hard to ensure that Unitarians would continue to have a learned ministry. Yet he saw the preacher as more a spiritual guide than a teacher. He said, “[The preacher’s] object is not so much to form the Christian character, as to beget the Christian nature. His aim is the regeneration of man, not his development.”

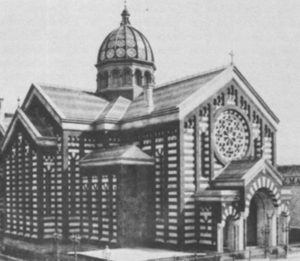

During Bellows’s ministry the church operated a free school for poor children and a Sunday school (still something of a novelty at that time), and completed two major building projects. Bellows encouraged or collaborated with several of the congregation’s prominent citizens on innovative social projects. Among them were Peter Cooper, founder of Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a free college for the education of the working class; Calvin Vaux, a designer of Central Park (with Frederick Law Olmstead); and Henry Bergh, who started the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Authors William Cullen Bryant and Herman Melville were also congregants.

In 1847 Bellows founded a Unitarian newspaper, the Christian Inquirer. As an editor and writer for this and its successor publication, the Liberal Christian, over a period of three decades, he exercised a broad influence upon the Unitarian movement. He later purchased scholarly journal, the Christian Examiner, which he edited, 1865-69.

Bellows agreed with Theodore Parker on the features of “essential Christianity,” and acknowledged that “a pious heathen, might be [as] acceptable in the sight of God as a Christian.” He appreciated and welcomed the advances of science. Not expecting to abolish religious differences, he thought in terms that encompassed religion in general. Yet he felt that a Unitarianism divorced from Christian historical roots was not sustainable. He wrote, “I am a Christian in faith & theory, an accepter & teacher of historic Christianity; & altho I am free to cancel all the misgrowths & accretions & monstrosities of the Christian Church system-yet beneath all, I feel that the most saving truth[s] have been & continue to be in action. I wish no break of continuity; no rejection or denial of Christian faith & symbols-but only such enlargement of view & purification of feeling-as will enable the world to profit by the more spiritual conception of Christ’s teachings, we are able to form & entertain.”

Above all, Bellow’s theology was driven by his sociological analysis of how religions change over time. Successful religions, he believed, continue to transform lives they touch, though the manner in which they do so may have to change with the times. In 1859 Bellows delivered an address, The Suspense of Faith, before the Harvard Divinity School Alumni Association. He questioned the capacity of 19th-century Protestantism to meet deep human needs, because of its unbalanced focus on the individual’s direct connection with God. The assumption that anyone can understand ancient Scriptures, with no help from the church as an interpretive community of discourse, “vacates the church.” He contended that Unitarian churches, having carried an emphasis on the capacities of the individual to its furthest extreme, had “shown the world the finest fruits and the rankest weeds of the Protestant soil.”

It seemed to him the Unitarian pendulum must soon reverse its swing. He wrote, “There are two motions of the spirit in relation to God, his Creator and upholder, [both] essential to the very existence of generic or individual Man-a centrifugal and a centripetal motion-the motion that sends man away from God, to learn his freedom, to develop his personal powers and faculties,

relieved of the over-awing and predominating presence of his Author; and the motion that draws him back to God, to receive the inspiration, nurture, and endowment, which he has become strong enough to hold.”

He went on to set forth his theology of the church as an institution. “I am convinced,” he said, “that, in accordance with the whole of Providence, every radically important relationship of humanity is, and must be, embodied in an external institution.” Institutions are “the only constant and adequate teachers of the masses.” He also believed that some divine blessings are inherently social, that the Holy Spirit communicates with “Humanity, and not with private persons,” through communally celebrated “commemorative days” and communal use of “holy symbols.” He urged Unitarian churches to reclaim the importance of public worship and of sacramental acknowledgment of human dependence on gifts not made by human hands.

Initially, the address was hotly criticized by those who heard it as a retreat from reason, science, free will, and respect for the individual. By way of clarification, Bellows preached and published A Sequel to the “Suspense of Faith” later in the year. He called for no retreat from modernity but rather a broadening of Unitarian focus to include the arts, the spirit, and the excellence of effective public worship. And his apparent retrieval of features of Roman Catholic religion was based less upon admiration for Catholics than concern for Protestantism. To combat what he considered a threat, he thought “we must take immediate steps to organize Protestantism more efficiently and on less sectarian ground.”

Before the Civil War Bellows served on the Board of Meadville Theological School, raised major funds for Antioch College, of which Horace Mann was the founding president, and was active in movements for the reform of prisons and civil service. But his greatest public service was occasioned by the camp conditions suffered by the soldiers who fought to preserve the Union.

Even before the terrible toll of battlefield deaths began, alarming reports indicated that great numbers of Northern soldiers were dying in the camps from bad food, inattention to sanitation, and grossly inadequate medical care of the wounded. In 1861 Bellows helped Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell and those she had gathered in New York City to establish the Women’s Central Organization of Relief. But unresponsive Army officers made no move to receive the material aid or to deploy volunteer nurses such citizen organizations offered to send, until the Women’s Central sent Bellows, along with a committee of distinguished and civic-minded men, to lobby for official recognition and military cooperation.

The committee was successful. Government officials chartered the U.S. Sanitary Commission to organize the collection of donated medical supplies and to advise both the civilian government and the Army regarding required public health and medical measures. Bellows was made president of an organization empowered to address a desperate and vast situation: trains filled with corpses left the filthy camps around Washington, D.C. daily. After the Commission’s extensive investigation and long, patient lobbying, the Army generals at last began to respond and camp conditions improved. As the fighting intensified and continued, the Commission virtually took charge of evacuation and treatment of tens of thousands of the wounded.

The Sanitary Commission was the first health and social welfare project in the world organized on such a large scale. It pooled and coordinated the efforts of tens of thousands of volunteers spread over thousands of miles. Its policy of treating captured, wounded Rebels as well as the North’s injured inspired the Geneva Convention on War. When the International Red Cross was formed, its organizational design was modeled after that of the Sanitary Commission.

Bellows encouraged the young minister of the First Unitarian Church of San Francisco, Thomas Starr King, to put his stunning oratorical gifts to use in service to his country. Starr King did, raising over a million dollars for the Sanitary Commission in countless mining camps and towns all over the State and keeping California in the Union. Bellows also recruited Mary Livermore and Frederick Law Olmstead for the Commission.

Meanwhile, in Unitarian church circles Bellows had become something of an unofficial, informally acknowledged ministerial settlement officer. Both his extensive travels on behalf of the Sanitary Commission-which often involved Unitarian church members-and his work in support of Antioch College and the Meadville Theological School brought him into close association with a wide range of Unitarian churches and ministers. Both lay leaders and ministers consulted him about suitable matches. He went to San Francisco upon Starr King’s death, helped to hold the grieving church together, and arranged Horatio Stebbins’s call as the church’s next minister.

Since 1825 the American Unitarian Association (AUA) had been the only Unitarian organization promoting expansion of the Unitarian faith. (The Sunday School Society was organized in 1827 to produce educational materials, and the Benevolent Fraternity in 1834 to serve Boston’s waterfront poor.) Members of the AUA were individuals, mostly ministers. They paid a small annual membership fee, raised some modest funds from non-members, and annually elected a board which oversaw the work of a part-time Secretary and his staff. Congregations were not AUA members. The average annual income of the AUA from 1825-65 was $8,000.00. The organization did send a few mission “agents” from time to time to explore the possibility of church “planting” in the West. But, for lack of funds, the AUA did little more that publish and distribute tracts and books.

Bellows believed that Unitarians needed a new organization for several reasons. Church membership had been stagnant for two decades, but any ability to raise funds for support of missionaries was stymied, in part, by still unresolved differences stirred up in the Transcendentalist controversy. Bellows believed that if the Unitarian movement were to survive and grow, the churches would have to find new institutional means of accommodating varying theological positions. He thought himself theologically and politically equipped to lead efforts to create such an accommodation. He wrote, “I am I believe on both sides of all great questions because truth rides a-horse-back; her limbs are invisible to each other & in opposite stirrups, but her trunk is one.”

His work on the Sanitary Commission had brought Bellows face to face with the fact that American society was changing rapidly. The time was ripe for significant Unitarian expansion, if only its churches could be unified and the scope of their concerns broadened. Time spent with young soldiers and volunteers had convinced him that many Americans were “thoroughly undermined in the foundation of the faith of their parents” and were “trying to find some substitute in ethics or pseudo or real science, for a religion in which they cannot longer believe.”

At the same time he had also seen the great work that could be done by devoted and well-coordinated volunteers. The old informal patterns of cooperation among churches of the New England Way-in which all the Unitarian churches had been formed-were no longer adequate. The times demanded equally devoted and well-coordinated work on behalf of all those who should find a home in liberal churches.

In 1864 Bellows reported to a special meeting of the AUA on a recent trip to California. He pictured the Unitarian movement welcoming religious seekers across the land, and thus serving as a unifying force a in a war-torn country. He urged the formation of a national organization much larger than the AUA, at whose meetings each church would be represented by its minister and two lay delegates. The gathering voted to increase its current fund-raising target from $8,000 to $100,000 and appointed a committee, with Bellows as chair, to call an organizing conference in New York City.

At this point Bellows even hoped the embrace of the conference might extend beyond the significant theological diversities among Unitarians. He obtained from a New York Universalist minister a list of Universalist ministers who might accept an invitation to join, should the conference open its membership to all liberal Christian congregations.

As broad as he cast his organizational net theologically, Bellows was determined to have the new denominational organization directed by wealthy men of the established business class. The conference meeting notice asked churches to send “the strongest, wisest, and most prudent men of our body.” His views were echoed in a prominent article in the Christian Register just prior to the conference. “Our parishes have wisely chosen some of their best men to represent them,” it boasted. “They are, preeminently, men of affairs. They have been accustomed to deal with life and things in their practical aspects, and judge of opinions and men on their bearings on direct and immediate results.”

The new body convened in New York City April 5-6, 1865. Some 600 ministers and lay delegates attended. More than three-fourths of the Unitarian churches were represented. James Freeman Clarke gave the opening address. Two resolutions were adopted early on, clearly stating that the conference’s purpose was to organize the Unitarian faith in a comprehensive fashion, “but always on principles accordant with its Congregational or independent character.” Actions and resolutions were to be understood as expressing the views of the majority those present, in no way presuming agreement or obliging action in the churches, and without excluding from fellowship either delegates present or member congregations who held opposing views. This affirmation of congregational self-governance, even in the act of forming an association of congregations for purposes of voluntary cooperation, established the basic model for all subsequent North American associations of Unitarian (and now also Universalist) congregations.

Bellows felt that if the new body was to be effective in mobilizing the congregations to work toward bringing in new people and building new churches, it was essential that delegates adopt a statement clearly identifying the Unitarian movement as Christian. “I am persuaded that history shows no progress in any sect not built upon dogma,” he wrote privately to Edward Everett Hale, “& that, inconvenient as it is, we must find & enunciate our creed.” In a letter to James Freeman Clarke, he emphasized how flexible his idea of a creed could be: “We want to describe a large eno’ circle to take in all who really belong with us-and provided one, & the fixed leg of the compasses is in the heart of Jesus Christ I care very little how wide & far the other wanders.”

Delegates at the 1865 conference chose to limit membership to Unitarian churches and to name the new body the National Conference of Unitarian Churches, but in 1866 the name was changed to the National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches. The National Conference institutionalized the strong role of lay leaders in its deliberations, just as its member congregations had done since Colonial times. The preamble to it earliest bylaws described member congregations as “disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ, dedicated to the advancement of his Kingdom,” though nowhere did the document imply any creedal test for membership either in the Conference or in member churches. A small number of Transcendentalist radicals, who objected to the Christian language, departed from the Conference and formed, in 1867, the Free Religious Association (FRA). Members of the FRA, however, were not congregations, but only individuals whom the “broad church” leaders of the National Conference never ceased urging to return.

Death

Bellows served as president of the National Conference, with short breaks, until 1880. He actively served his congregation, his community and the Unitarian movement until his death. He died in New York City after a brief illness. Edward Everett Hale read the eulogy at his well-attended funeral. His remains were transported by train to Walpole, New Hampshire, for a second service and burial in the family plot. At the May 1882, meeting of the AUA, a time was set aside to honor Bellows for his many contributions. Frederic Henry Hedge gave an address, in which he called him “our Bishop, our Metropolitan.”

Henry Whitney Bellows was 19th century American Unitarians’ great institutionalist. It is difficult to imagine the movement’s survival without the continuing fruits of his creative work. Yet he has been underappreciated. His Transcendentalist opponents broadcast in many published writings their rejection of both his theology and his churchmanship, and they were far better writers than he. Their estimates of him misrepresented his both his thought and his aims. Conrad Wright and other Unitarian historians have investigated the vast wealth of information available in Bellows’s papers and have begun to restore him to the forefront of 19th-century Unitarian history.

Sources

The Bellows Papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. His autobiographical writings are two sermons called “First Congregational Church in the City of New York” (1899) and “The Sanitary Commission,” North American Review (1864). His book-length publications are Re-Statements of Christian Doctrine, in Twenty-Five (1860), The Old World in Its New Faces: Impressions of Europe in 1867-1868 (1868-69), Twenty-Four Sermons Preached in All Souls Church New York, 1865-1881 (1886). Early memoirs of Bellows include John White Chadwick, Henry W. Bellows: His Life and Character (1882); Anna Langdon Bellows, Recollections of Henry Whitney Bellows (1897); and Thomas Bellows Peck, Henry Whitney Bellows: A Biographical Sketch with Portrait (189-). The standard biography, which includes an extensive bibliography of Bellows’s sermons and other writings is Walter Donald Kring, Henry Whitney Bellows (1979). Among short biographical articles are Edward Everett Hale, “The Fallen Cedar,” an obituary in The Christian Register (February 2, 1882); David Robinson’s entry in his The Unitarians and the Universalists (1985); Robert D. Cross’s, entry for American National Biography (1999); and Mark Harris’s entry in his Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism (2004). Conrad Wright wrote an important article, “Henry W. Bellows and the Organization of the National Conference,” reprinted in The Liberal Christians (1970). See also George Willis Cooke, Unitarianism in America (1902), Charles William Wendte, The Wider Fellowship, volume 2 (1927) and Conrad Wright, A Stream of Light (1975).

Article by Mark Evens

Posted June 4, 2004