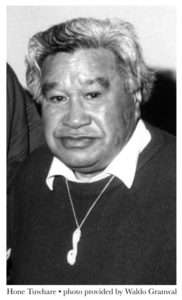

Hone Tuwhare (October, 1922-January 16, 2008) was one of the leading poets of the twentieth-century. Building on his Māori and Scottish background, his poetry reflected, critiqued, and celebrated New Zealand culture and its people. He was a social justice advocate, a defender of the working class, and an advocate for the Māori. Coming from a humble background with a limited education he went on to win numerous awards and fellowships and gain an international reputation. Tuwhare was closely associated with New Zealand Unitarians for many years; in the 1950s he was active in the Workers Educational Association housed in the Auckland Unitarian Church, in the 1960s he attended the Auckland church with his family, and he regularly published poetry in the journal Motive, a publication of the New Zealand Society of Unitarians.

Born at Kokewai, Mangakahia a country district a few kilometers from the town of Kaikohe in the far north, Tuwhare was of Ngapuhi and Scottish descent. Life was hard for the family, of five children he was the only one to survive childhood. His parents moved to Auckland when he was four, but returned north when his mother, Mihipaea, became ill. She died of consumption when he was five years old. Hone and his father returned to Auckland where he attended primary schools in Avondale, Mangere and Freeman’s Bay. He had a keen interest in English and finished Beresford Street school in standard six, top in his class in that subject. Speaking Māori until he was nine years old, he was encouraged by his father, Pene (also known as Ben), an accomplished orator and storyteller in Māori, to develop his abilities in the written and spoken word. He was raised in the Māori way of life but he also read the King James Bible and Shakespeare with his father and they on occasion would attend St. Matthew’s Anglican Church in Auckland.

As the Depression began to take hold in New Zealand there was no money in the Tuwhare household for Hone to go on to secondary school. At the Beresford Street School, the last he attended, the headmaster had suggested Te Aute Māori Boy’s College for his further education. He was without a job for a year until his father arranged an apprenticeship for him at New Zealand Railways. Starting in January 1939, he trained to be a boilermaker at the Otahuhu workshops. There he was introduced to Marxism and in 1942 joined the Communist Party.

An avid reader, Tuwhare was mostly self-educated. He was a union representative to the Workers Educational Association (WEA) where he had access to the library, attended drama club productions, and met members of the Auckland Unitarian Church working in the WEA. In 1948 the first post war Auckland Unitarian Minister, Ellis Morris, was tutoring at the WEA, as had his predecessors before him. WEA was housed in the Old Grammar School building in Symonds Street until fire destroyed the building and library in 1949. For the next eighteen years the Auckland Unitarian Church would provide free use of the downstairs rooms in its building. In 1977 when a new Adult Education Centre was opened near Auckland University the WEA was finally re-housed.

The Left Book Club and the co-operative Progressive Bookshop, in Darby Street, Auckland, gave Tuwhare access to a range of Russian, American, and English literature by Marxist and anti-fascist writers. It was there that Tuwhare met Jean McCormack, a bookshop worker. Soon they were going out together.

Tuwhare also met and became friends with R.A.K. Mason, the editor of the Communist Party newspaper In Print and later co-editor of the Peoples Voice. Tuwhare helped with distribution. Both were active in the trade union movement but Tuwhare didn’t realize that Mason was also a poet, until Jean McCormack told him. Mason encouraged Tuwhare to write freely without regard for formal structure. Mason’s biographer later observed that it was not just their politics and poetry that brought them together: “It was their likeness of character- Tuwhare’s humility, modesty and earthy sense of humour… that cemented an enduring bond between them.”

It was through R.A.K. Mason’s urging that Tuwhare became involved with the struggle over Māori land issues. In June 1943 Tuwhare joined 200 trade union members to help the Ngati Whatua people build a 300 foot palisade with stakes set in concrete around their marae; to prevent the local government evicting them from the last of their land on the Auckland waterfront. The workers built the fence in one day and the land was saved.

By the last year of the war, Tuwhare was in military camp training as a soldier, having previously been rejected, probably because he was color blind. Peace arrived before his unit could be sent overseas. With the formation of the J-Force for the occupation of Japan in 1946 he saw the chance of overseas service and re-enlisted. In Japan he went to Hiroshima where he witnessed devastation on a scale he had not imagined was possible. The effect of his visit to Hiroshima would emerge years later in his poetry.

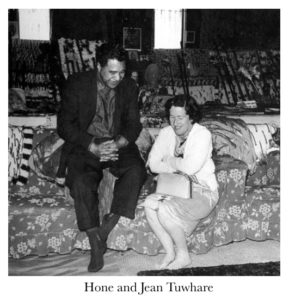

Tuwhare and Jean Agnes McCormack were married in 1949 at the Auckland Registry Office. It was through Jean that he came to the Auckland Unitarian Church, although he was already familiar with it through his involvement with the WEA. Jean described herself as: “Having been brought up a third generation agnostic… However, for many years my mother attended the Unitarian Church, where she received much benefit and stimulation of thought from the services heard there, and where she made many life-long friends. If we lived in Auckland, it would please us very much (and my parents also) to take our children to the Unitarian Church.” In the 1960s they attended the Auckland Unitarian Church with their three sons. Jean’s mother, Edith, passed her love of poetry on to her daughter while her father Duncan, who had been imprisoned as a conscientious objector during the Great War, supported Hone in his various causes.

After working in Wellington for a few years following their marriage, Tuwhare was employed as a boilermaker on the large Waikato River dam-building projects. Between 1953 and 1961 he and the family lived in the worker’s village in the lake Taupo district. The Hungarian uprising of 1956 was something of a watershed for him, he found he could not support the Russian intervention and along with many others left the Communist Party. He remained a committed trade unionist. After leaving the party he found he had more time for reading and writing and he corresponded with Ron Mason, who commented on his poems and encouraged him to think about publication.

Tuwhare found a friend in Phoebe Meikle who was an editor with the Blackwood and Janet Paul firm from 1960 to 1965. She “very much wanted a Māori voice to be widely heard.” Phoebe had taught English at Takapuna Grammar School for many years and Jean McCormack had been one of her students. Tuwhare told Phoebe: “You taught me my grammar because you taught it to Jean and she taught it to me.”

The Auckland Unitarian Church connection provided an introduction to the wider Unitarian community where Tuwhare met people with literary interests similar to his own. In particular, the quarterly journal Motive published in conjunction with the New Zealand Society of Unitarians, proved to be an enthusiastic outlet for his poetry. The Society and Motive were the initiative of Maurice Wilsie, an American psychologist who was the lay minister at the Auckland Unitarian Church at the time. His wife Diana was the Motive circulation manager.

Tuwhare continued working with Motive after Nancy Fox took over the editorship in 1960. Nancy Fox also wrote poetry so they soon were also close friends. She moved to Whakatane in 1961 the same year Jean and Hone Tuwhare moved to Te Mahoe; both towns located in the Bay of Plenty region on New Zealand’s North Island. On one occasion Joan Walsh, Nancy Fox’s close friend and the President of the New Zealand Unitarian Society came to see her and found the Tuwhare family already visiting. Joan recalled that it was difficult to get a word in as “Hone did most of the talking with Nancy.”

Tuwhare had another friend active in the New Zealand Society of Unitarians, Lincoln Gribble, the associate editor of Motive. Trained as a Unitarian minister, Lincoln was teaching at Te Aute College where he resided as a House Master with his wife Dolores and their children. Within handy driving distance of Lincoln, Tuwhare would often visit to discuss poetry, literature, and life.

In the spring 1962 edition of Motive, Nancy Fox wrote: “A good deal of [this issue] was written by New Zealanders; most of it was written especially for us (we mention especially Hone Tuwhare’s poem) or was sent to us to print for the first time.” Readers were told that the poem in question, entitled “Mauri,” referred to the “material symbol of the hidden principle protecting vitality; talisman, life principle…”

Tuwhare’s first book No Ordinary Sun came out in September 1964, from the publisher Blackman and Janet Paul. The key poem “No Ordinary Sun” expressed his horror with what he had seen at Hiroshima after World War II. The book was dedicated to his father Pene. Ron Mason wrote the forward: “… it is with more than individual pleasure” he said, “that I welcome this book from my old and close friend, fellow poet and fellow worker… Here—and I think this is for the first time—is a member of the Māori race qualifying as a poet in English and in the idiom of his own generation, but still drawing his main strength from his own people.”

In 1965 Motive reported that following successful readings in the Bay of Plenty, Tuwhare was giving poetry readings in Auckland and that a third edition of No Ordinary Sun was in preparation. The book would be reprinted 10 times over 30 years and was the most widely read single poetry collection in New Zealand’s literary history.

Jean meanwhile was having a successful year at Auckland Teacher’s College undertaking an intensive teacher training course. Her lecturer in English, Augusta Ford, encouraged her to also write poetry. Motive published two more of Hone Tuwhare’s poems, “Who Is Testing Tonight” and the “Prodigal City,” which were read in the Family Services conducted at the Auckland Unitarian Church by Noel and Thelma Blyth. After reading the poems Noel said: “Hone Tuwhare is our poet. I think he nicely sets a mood of this big sprawling city in which our problems, our children’s problems and our Church problems are set.”

The Blyth’s had begun a very successful revitalization of the Auckland Unitarian Church in 1965 with their Family Services, a programme they were to continue for the next two and a half years. Attendances grew rapidly in response to their humanist presentation invigorated with Thelma’s musical repertoire, especially her folk singing. Noel Blyth remembers Jean and Hone Tuwhare and their children attending a number of the services at this time. On one occasion when Thelma sang We Shall Overcome, Tuwhare came up to them afterwards and said how Thelma’s singing of that song “very nearly had me in tears.”

In 1968 Hone Tuwhare appeared with Pete Seeger in a joint performance in St. Matthew’s Anglican Church in Auckland; at a packed anti-Vietnam war rally. This was the church his father had taken him to as a child. The December 1968 issue of Motive contained a further poem from Hone, “In October, Mary,” one of his few religiously themed poems:

Today, with the sun friendly

by her side

she takes her delight

in casting a bulbous shadow

on the hard track: her

breasts weep a greedy mouth.Now is she pummelled

And elbowed

to a shifting surface

of floating bumps: belly-skin

stretched to fine veins

criss-crossing.Obsequiously

the wind retreats

before the polka-dotted

belly-full that is her

spinnaker dress: her facequirks a mona lisa

for tomorrow she

plump majesty

shall wear a crown of pain

for His coming.

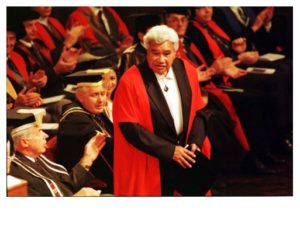

In 1969 Hone was awarded a Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago. After Jean and Hone separated in 1972, Jean later included both family names in her surname, which became McCormack-Tuwhare. She taught in various Auckland primary schools for the next 20 years and wrote short stories and poems, a number of which were published in the New Zealand Listener and ka mate ka ora, a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics. Jean and Hone kept in touch over the years and she wrote poems about him. Neither of them remarried.

The 1970s saw the publication of four new poetry collections and the award of a second Burns Fellowship in 1974. Tuwhare was a Hocken Research Fellow at the University of Otago in 1983 and a Berlin (Germany) writer in residence in 1985. Two further poetry collections were published and a play was produced during the 1980s. In 1991 he was awarded a University of Auckland Literary Fellowship.

Until 1992, Tuwhare had lived in the city of Auckland on New Zealand’s North Island. In 1992 he bought a beach-front crib (a small holiday cottage) at Kaka point, Otago on New Zealand’s South Island. Far from the bustle of the city and close to nature, he hoped to spend more time writing. Dunedin, the nearest city, had been settled by Scottish immigrants who brought their Presbyterian beliefs and a strong educational tradition, founding Otago University, the first in the country. At Kaka point, Tuwhare befriended local shopkeepers and neighbors and participated in the Kaka Point Writers Group. He increasingly depended on friends for assistance as he aged.

In 1999 Tuwhare was the second person to be appointed as a Te Mata Poet Laureate for New Zealand. Three further poetry collections were published and he received honorary Doctorates of Literature from Otago and Auckland Universities. Tuwhare was among ten of New Zealand’s greatest living artists named as Arts Foundation of New Zealand Icon Artists in 2003. In the same year he was awarded one of three inaugural Prime Minister’s Awards for Literary Achievement.

Hone had definite views on death; believing death was something he had a right to control; he was a member of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society, as was Jean. He did not want to lie on a marae when he died as was Māori custom, but wanted to be cremated and have his ashes scattered on four harbors. When the time came this wish was to be denied him. His body was laid on the te Kotahitanga Marae for two days and he was buried at the Wharepaepae Cemetery, near Kaikohe. Jean attended the funeral as a respected member of the family with their three sons. In 2008, after his death, Jean published the poem “Sand” in ka mate ka ora, a New Zealand journal of poetry and poetics:

I walked on this beach

with the Māori father of my sons

fifty years ago and more…

He didn’t tell me the grains of sand

on the beach were his.

We crossed the creek

and wrote our names on a rock

encircled with a heart.We danced at the Pirate Shippe

waltzes and foxtrots

and the Levita.

We moved in different times and spaces now.

I walk the same beach in the winter.

And still no word from him about the sand.

The memorial service for Hone Tuwhare at the Auckland Unitarian Church, held a few months after he died, featured the song We Shall Overcome which Hone loved hearing Thelma Blyth sing. The church was filled for the service which included readings from his poetry.

Sources

Letters, artwork, sound recordings, and other items are held in the Hocken Library Heritage Collections at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. The beach-front crib (holiday cottage) near Kaka Point occupied by Hone Tuwhare from 1992 to 2008 was purchased by the Takutai Trust with the intention that it would be gifted to the Hone Tuwhare Charitable Trust on completion of restoration. Consult the Hone Tuwhare Charitable Trust website (honetuwhare.org.nz) for more information. The National Library of New Zealand (natlib.govt.nz) has an extensive Hone Tuwhare collection including copies of Motive, the quarterly journal of the New Zealand Society of Unitarians. Poetry collections by Hone Tuwhare include; No Ordinary Sun (1964), Come Rain Hail (1970), Sapwood and Milk (1972), Something Nothing (1973), Making a Fist of It (1978), Selected Poems (1980), Year of the Dog (1982), Was wirklicher ist als Sterben (1985), Mihi: Collected Poems (1987), Short Back & Sideways (1992), Deep River Talk: Collected Poems (1994), Shape-Shifter (1997), Piggy-back Moon (2001), and Oooooo……!!! (2005).

The primary biographical work is Janet Hunt, Hone Tuwhare A Biography (1998). Unfortunately Hunt overlooked Hone’s Unitarian connections. A ten-minute video documentary is available (nzonscreen.com) while an illustrated biography is available on-line in The Encyclopedia of New Zealand (teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/6t1/tuwhare-hone). For more on Tuwhare’s relationship with R.A.K. Mason see Rachel Barrowman, Mason: The Life of R.A.K. Mason (2003). Also useful are Rachel Barrowman, A Popular Vision: The Arts and the Left in New Zealand, (1991) and Cybele Locke, Workers in the Margins: Union Radicals in Post-War New Zealand, (2012). A profile of Hone Tuwhare is available on the website of the New Zealand Book Council (bookcouncil.org.nz). A short biography can be found in The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature (2013).

Thanks to Noel Blyth, Dolores Gribble, Joan Walsh, and Jean McCormack-Tuwhare for additional information and assistance. Thanks also to Waldo Granwal and Shalom Del’Monte who are credited in photo captions.

Article by Wayne Facer

Posted June 15, 2016