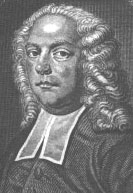

John Abernethy (October 19, 1680-December 1, 1740), called “the father of non-subscription”, was a prominent Irish Presbyterian minister who led many ministers and congregations out of the Synod of Ulster into a separate liberal-minded denomination, known today as the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland.

John was born in Brigh, county Tyrone. His father, also called John Abernethy, was a Presbyterian minister from Scotland who ministered at Brigh until 1684 when he moved to the congregation of Moneymore in county Londonderry. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 Abernethy’s father travelled to London to present a loyal address to the new King, William of Orange. In the turmoil that took place in Ireland at this time young John was sent to stay with his mother’s family in Scotland. His mother and the rest of the family took refuge in the city of Londonderry. Though his mother survived, all his siblings perished in the siege of the city.

At the age of thirteen Abernethy followed the well-trodden path of Irish Presbyterians to the University of Glasgow. He graduated MA in 1696 and then transferred to Edinburgh to pursue the study of theology. In 1702, passing the first step to ordination, he was licensed by the Presbytery of Route. Within the next year he was admitted as a probationer in the Presbytery of Antrim. He spent a short period in Dublin at the time of the controversy surrounding Thomas Emlyn, ultimately imprisoned for denial of the Trinity.

At the end of his training Abernethy received calls from two congregations, from Coleraine where his father, now in poor health, had ministered since 1691, and from Antrim which in 1701 had built a new meeting house. Abernethy chose to go to Antrim and ministered there, 1703-30. He was moderator of the General Synod of Ulster, 1715-16.

Abernethy was a man of intense spiritual discipline and a conscientious pastor. He preached two or three sermons every week displaying both a thorough knowledge of the scriptures and an active interest in current trends in theology and philosophy. In 1705 he founded a meeting, subsequently known as the Belfast Society, of ministers and lay people who gathered to discuss the Bible and recent theological scholarship. Members pooled their resources to buy new books and prepared papers on the latest publications. They trained themselves to engage in theological disputation and gradually began to challenge accepted religious notions of their day. A nineteenth-century Presbyterian historian described the Belfast Society as a “seed-plot of error”.

An unusual feature of Abernethy’s Antrim pastorate was his ministry to the Catholic, Irish-speaking population who lived nearby, along the shores of Lough Neagh. Doubtless his main aim was to win converts. After the death of his first wife in 1712, he devoted an increasing amount of his time to visiting and preaching amongst the Catholics. So he must have had some knowledge of the Irish language, though he was never included in any list of Irish speakers drawn up by the Presbyterian synod. His ministrations brought few conversions, but the community appreciated his pastoral concern. In 1718, when he was resisting pressure from the General Synod to move to a charge in Dublin, a delegation of Irish speakers arrived at the Synod meetings. Through an interpreter they told the assembled delegates of “Mr Abernethy’s usefulness among them, praying for his continuance in the Congregation of Antrim, that they might still enjoy the advantages of his labours”.

On two occasions the congregation of Usher’s Quay in Dublin issued a call to Abernethy. Eventually, the Synod of Ulster ordered him to leave Antrim and take up the charge in Dublin. After much heart-searching and even a trial visit to Dublin of three months, Abernethy defied the Synod and refused to move. He felt he was of greater usefulness in Antrim than he would be in the capital.

In 1719 Abernethy preached a sermon before the Belfast Society, Religious Obedience founded on Personal Persuasion, taking Romans 14:5 as his text. He had been influenced by the ideas of Benjamin Hoadly, a Church of England bishop who declared two years earlier, preaching before King George I, that Christ sanctioned no visible Church authority. Abernethy took his own stand on the right of private judgement and the individual’s responsibility to employ the God-given faculty of reason in interpreting scripture. He said that “to do anything under the notion of service to [God] without the approbation of our understandings is not to serve him at all, but indeed to affront him, and to debase ourselves beneath the dignity of our nature by neglecting to improve our Reason which is our greatest excellency.”

Publication of his Religious Obedience the following year engulfed Irish Presbyterianism in a storm of controversy. Abernethy was answered in print by the Revd John Malcome who accused him of trying to bring a “New Light” into the church. A sustained pamphlet war followed. Much of the debate came to focus on the use of creedal formularies and the authority of churches to enforce them. Within Irish Presbyterianism the issue became whether or not to subscribe to the Westminster Confession. Hence the term, Non-Subscribers, applied to Abernethy and his supporters.

Abernethy had left behind the Calvinism of his forebears. He propounded an Arminian theology underpinned by a belief in the freedom of the individual conscience. Although Non-Subscribers were frequently accused by their opponents of unorthodoxy on the question of the Trinity, they did not at this stage explicitly develop unitarian views. In 1725, after years of heated disagreement, the Non-Subscribing ministers and their congregations were placed together in the Presbytery of Antrim. The following year they were formally excluded from the Synod of Ulster.

Abernethy did at last move to Dublin in 1730, though not to the congregation the Synod had originally ordered. He succeeded Joseph Boyse as the minister of the Wood Street congregation, perhaps the most influential in the city, eager to acquire the services of a scholarly minister of proven abilities and liberal outlook.

Throughout his ministry Abernethy was concerned for the protection of the civil rights of religious dissenters. He published a number of works opposing the Test Act, which excluded non-Anglicans from public office. In these he crossed swords with Jonathan Swift who had earlier attacked the Presbyterians in his Letter concerning the Sacramental Test, 1708, and who later returned to the offensive with works such as The Advantages Proposed by Repealing the Sacramental Test, 1732, and The Presbyterian Plea of Merit, 1733. Abernethy also published Discourses concerning the being and natural perfections of God, 1740, which became a standard textbook in Scottish universities and English dissenting academies.

Death

Abernethy died in 1740 and was succeeded as minister at Wood Street by James Duchal.

Sources

Abernethy’s diaries, which were available to James Duchal have been lost for some time. The most important contemporary source for his life is Duchal’s A Sermon on Occasion of the much Lamented death of the Late Reverend Mr. John Abernethy (1741). Other sources include

Records of General Synod of Ulster, vols.1 & 2 (1890 & 1897); Munimenta Alme Universitatis Glasguensis, 3, (1854); and Manuscript Minutes of the Presbytery of Route. Abernethy’s defence of the right of dissenters to hold civil office was published in The nature and consequences of the Sacramental Test considered (1731), and Reasons for the repeal of the Sacramental Test (1733).

There are a number of biographies of Abernethy: anonymous, ‘The Father of Non-Subscription in Ireland’, The Disciple (1882); F. J. Bigger, The Two Abernethys (1919); Richard B. Barlow, ‘The Career of John Abernethy (1680-1740), Father of Nonsubscription in Ireland and Defender of Religious Liberty’, Harvard Theological Review (1985); A. W. Godfrey Brown, ‘John Abernethy’ in G. O’Brien and P. Roebuck, ed., Nine Ulster Lives (1992); R. Finlay Holmes, ‘The Reverend John Abernethy: The Challenge of New Light Theology to Traditional Irish Presbyterian Calvinism’ in Kevin Herlihy, ed., The Religion of Irish Dissent (1996); and an entry by M. A. Stewart in the forthcoming New Dictionary of National Biography (due for publication in 2004). Witherow, T., Historical and Literary Memorials (1623-1731) (1879) is a very useful biographical study of eighteenth century clergy. See also J. S. Reid, History of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, 3 vols, (1867) and J. McConnell, ed., Fasti of the Irish Presbyterian Church 1613-1840, (1951).

Article by David Steers

Posted January 22, 2002