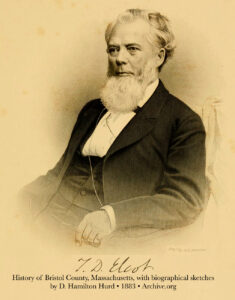

Thomas Dawes Eliot (March 20, 1808-June 14, 1870) was a renowned Massachusetts attorney and a passionate progressive politician in the years leading up to and following the Civil War. A dedicated and capable Unitarian church leader, he served as president of both the National Conference of Unitarian Churches and the American Unitarian Association. Born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the first child of William Greenleaf Eliot (1781-1858) and Margaret Greenleaf Dawes Eliot (1789-1879), he was named for his grandfather Thomas Dawes, Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. His great-grandfather Colonel Thomas Dawes had been a Revolutionary War patriot. His brother William Greenleaf Eliot, Jr. born three years later would become a distinguished Unitarian clergyman. His brother Frank was killed in action at Chancellorsville, Virginia in May 1862.

Thomas Dawes Eliot (March 20, 1808-June 14, 1870) was a renowned Massachusetts attorney and a passionate progressive politician in the years leading up to and following the Civil War. A dedicated and capable Unitarian church leader, he served as president of both the National Conference of Unitarian Churches and the American Unitarian Association. Born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the first child of William Greenleaf Eliot (1781-1858) and Margaret Greenleaf Dawes Eliot (1789-1879), he was named for his grandfather Thomas Dawes, Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. His great-grandfather Colonel Thomas Dawes had been a Revolutionary War patriot. His brother William Greenleaf Eliot, Jr. born three years later would become a distinguished Unitarian clergyman. His brother Frank was killed in action at Chancellorsville, Virginia in May 1862.

At the beginning of the Nineteenth century, his father moved from Boston to New Bedford, Massachusetts in hopes of making his fortune in the rapidly expanding whaling industry. Soon thereafter, the war of 1812 crippled maritime commerce, and the family moved first to Baltimore, Maryland and then, in 1818, to Washington, D. C., where—probably through family connections—the senior Eliot obtained a position as a chief examiner in the Post Office Department.

Washington D.C. at that time was a rough community, so the two boys were sent back to New Bedford to receive their secondary education at Friends Academy, an excellent school established by the town’s large Quaker community, but by that date open to all. Eliot returned to Washington, D. C. to attend the new Columbian College where he studied the classics, calculus, astronomy, contemporary philosophy, and political thought. Graduating with honors in 1825, he was chosen to speak at the college’s first Commencement in the presence of President Monroe, General Lafayette, and other public officials. In 1829 he was awarded the degree of Master of Arts. During this period he also began reading the law in the office of William Wallach (1788-1835) and with an uncle, Chief Justice William Cranch of the U.S. Circuit court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Moving back to New Bedford in 1830, Eliot continued his legal studies with Charles H. Warren, soon they entered into a partnership. When Warren was elevated to the bench, Eliot inherited a lively practice that extended over three counties. Eliot married Frances Lincoln Brock of Nantucket in 1834; they would have eight children. New Bedford, the center of the booming whaling industry was home to more than 400 vessels, and much of Eliot’s law practice involved insurance claims related to that industry. Not only was he deeply learned in the law, he attended court sessions regularly, even when he was not involved in a case. As a result, he was widely known for his depth of knowledge, understanding of precedent, and ability to present cases skillfully and eloquently.

The case that established Eliot’s public reputation involved a dispute between two sects of Quakers over who owned the Friends Meeting properties in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. The case that made him nationally famous involved the estate of Sylvia Ann Howland. A maiden woman, she left her estate of several million dollars to charities, with a modest bequest to her niece, Hetty Howland Robinson. Hetty produced another will which essentially left the entire fortune to her, but the attorneys for the estate, including Eliot, insisted that Howland’s signature was a forgery (probably by Hetty). The case was national news. In the end, the estate prevailed, and Hetty’s claim to her aunt’s fortune was rejected. Even so, when Hetty died at the beginning of the twentieth-century, she was reputed to be the world’s richest women, thanks to her miserly habits and a number of other inheritances.

Eliot’s most unusual victory related to the estate of another significant local woman, Mary Rotch, one of the great New Light Quakers. As the local Quaker meeting became increasingly rigid in the early 1820s, she withdrew and moved to New Bedford’s Unitarian congregation. Ralph Waldo Emerson was a frequent preacher there during the 1830’s, and the two became firm friends. Emerson credited Mary Rotch with having influenced the development of his own thought. Eliot was Rotch’s attorney. Never married, when Rotch died in 1848, she ignored her relatives and divided her substantial estate between her companion, Mary Gifford and her attorney–Eliot.

In the mid nineteenth-century, participation in public life was expected for an ambitious lawyer. Eliot served in both the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate. He twice declined offers of appointments to the Massachusetts bench. When a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives became vacant in mid-term 1854, he accepted the Whig nomination and was elected. New Bedford was a center of the Abolitionist movement, and he was committed to that cause. On May 10, 1854, shortly after arriving in Washington, he delivered an impassioned speech denouncing the Kansas-Nebraska Act because it would allow the residents of those territories to vote to allow slavery. The speech was widely circulated, and the Massachusetts Whig party tried to use it to show its sympathy with the anti-slavery movement. That same year he introduced a bill to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, the first Member of Congress to do so.

In the mid nineteenth-century, participation in public life was expected for an ambitious lawyer. Eliot served in both the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate. He twice declined offers of appointments to the Massachusetts bench. When a seat in the U. S. House of Representatives became vacant in mid-term 1854, he accepted the Whig nomination and was elected. New Bedford was a center of the Abolitionist movement, and he was committed to that cause. On May 10, 1854, shortly after arriving in Washington, he delivered an impassioned speech denouncing the Kansas-Nebraska Act because it would allow the residents of those territories to vote to allow slavery. The speech was widely circulated, and the Massachusetts Whig party tried to use it to show its sympathy with the anti-slavery movement. That same year he introduced a bill to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, the first Member of Congress to do so.

Eliot grew skeptical of the Whig party’s intentions and declined their invitation to run again. Instead, he became a leader in organizing the Free Soil party, and in the following years he was a major force in moving it into the new Republican party. He organized the first Republican meeting in Bristol County. Despite a unanimous vote, he declined the state Republican party’s invitation to be nominated for the office of state attorney general, but consented to preside over the next year’s state convention.

Perhaps because of his awareness of the impending war and his strong commitment to the Union cause, he accepted the Republican nomination to the House of Representatives in 1858, and was easily elected. He quickly became a leader of the anti-slavery forces in Congress. In this work, he was closely allied with his younger brother, William Greenleaf Eliot who was minister of the Unitarian congregation in St. Louis, Missouri. William Greenleaf Eliot was a major public figure in that contentious border state. It is probable that Eliot’s anti-slavery efforts were developed in close collaboration with his brother William. For example, the anti-slavery group in St. Louis would have been acutely aware of the potential consequences of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

As the Civil War began, the loyalty of Missouri to the Union was in serious doubt. On December 2, 1862, Eliot introduced in Congress one of the first emancipation bills. It authorized the President to “emancipate all persons held as slaves in any military district in a state of insurrection against the national government.” The military district most likely to be affected by the passage of the resolution was Missouri. It seems likely that the resolution was actually drafted by his brother William as a means of encouraging Missouri’s loyalty, and introduced at Willam’s request. It was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary where it died, but his brother William continued his political efforts to ensure Missouri’s loyalty. Another bill was introduced in 1862 calling for funds for compensated emancipation in Missouri. William, noting the strategic importance of the state, urged Eliot as Chairman of the Select Committee on Confiscation to do everything possible to secure its passage. His brother William even went to Washington to lobby for the bill. While that effort failed, a bill Eliot introduced calling for the confiscation of rebel property was enacted.

Eliot’s concern for the oppressed extended to the plight of American Indians and Chinese coolies. Coolies were recruited in China as contract laborers but treated like slaves once they arrived in California. He authored a bill, introduced in December 1861, passed by the Thirty-seventh Congress, and signed by President Lincoln in February 1862, which prohibited American vessels from engaging in the trade that brought coolies to the United States. In Congress, Eliot praised Haitian leader Toussaint L’Overture as a “remarkable man” and “a military genius.” He supported diplomatic recognition for Haiti saying, “. . . we have suffered this half century to pass away without consenting to perform an act of simple national justice.”

Eliot’s concern for the oppressed extended to the plight of American Indians and Chinese coolies. Coolies were recruited in China as contract laborers but treated like slaves once they arrived in California. He authored a bill, introduced in December 1861, passed by the Thirty-seventh Congress, and signed by President Lincoln in February 1862, which prohibited American vessels from engaging in the trade that brought coolies to the United States. In Congress, Eliot praised Haitian leader Toussaint L’Overture as a “remarkable man” and “a military genius.” He supported diplomatic recognition for Haiti saying, “. . . we have suffered this half century to pass away without consenting to perform an act of simple national justice.”

By 1864, Eliot was the Chairman of the House Committee on Emancipation. In that role, he introduced the pioneering bill to establish a Bureau of Freedmen’s Affairs. Its purpose was to determine all questions relating to persons of African descent and to make regulations for their employment and proper treatment on abandoned plantations. The bill passed March 3, 1865 by a majority of only two votes, and the Bureau was opened on December 6 following. Throughout his Congressional career, Eliot maintained a strong interest in the work of the Bureau and worked to give it the greatest support possible in its mission of feeding, clothing, and offering shelter and education. Originally authorized for only one year and plagued by a shortage of funds and corruption, it managed to survive for several years of service. At the end of the Civil War, Elliot expressed an eagerness to retire from the Congress, but in spite of his failing health he was prevailed upon to remain until 1869 when he refused to run again.

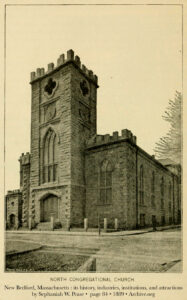

His extended family was deeply religious. His father, William Greenleaf Eliot, Sr. (1781-1858) was one of the founding members of the Unitarian congregation in Washington, D.C. and an active leader throughout his life. His younger brother, William Greenleaf Eliot, Jr. (1811-1877) was one of the most important clergy leaders in the entire Unitarian movement, especially among the conservatives. Eliot himself was active in the New Bedford congregation during his early years as a child and student. During his later years when he was active as a lawyer and politician, he assumed leadership roles in the work of the larger denomination. When the New Bedford congregation decided in 1833 to build a new church building, the young lawyer was one of the subscribers. For many years he served as Superintendent of the Sunday School, relinquishing the post only when he was elected to his first full term in Congress.

Eliot was one of the delegates that gathered in New York City when Henry Whitney Bellows called a national meeting in April 1865 to establish a more formal Unitarian denominational structure—one that would complement the older American Unitarian Association which consisted only of individual members. When his own New Bedford minister,William J. Potter, also a delegate, revealed his theologically radical convictions, Eliot aligned himself with the more conservative Christian wing of the movement led by his brother William, the Unitarian minister in St. Louis. Eliot used his strong parliamentary skills to assist the conservatives in creating a Christian preamble to the plan of organization in spite of the urgings of the Liberals to adopt a more inclusive formulation. A year later, it was Eliot who presided over the first annual meeting of the new National Conference of Unitarian Churches. Perhaps uniquely, at various times he served as President of both the National Conference and the American Unitarian Association. And in spite of his differing views from those of Potter, he always remained a loyal member of the New Bedford congregation.

Eliot died on June 14, 1870, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford. His wife Frances died in 1900.

Archival materials for Thomas Dawes Eliot are scarce. The Journal of Thomas Dawes Eliot: 1823-1824, discovered in 2001 is held by the Special Collections Research Center of Gelman Library at The George Washington University (Columbian College until 1904) in Washington, D.C. Gelman Library also hold Eliot’s notes on botany lectures given by William Staughton, the first president of Columbian College. Correspondence with General O. O. Howard, head of the Freedmen’s Bureau can be found in the Lincoln Memorial University library in Harrogate, Tennessee. An 1863 letter from W. H. Channing to Eliot about the death of his brother Frank can be found on-line at the Missouri History Museum website. Eliot’s congressional speeches, “The Territorial Slave Policy; The Republican Party; What the North Has To Do With Slavery” (1861), “Independence of Hayti” (1862), and “Freedmen’s Bureau” (1866) are available in print and on-line. Also available are the “New Orleans Riot Committee Report” (1867), and an “Anniversary Address” (1845) delivered to the American Institute of the City of New-York.

Brief biographies are found in Zephaniah Walter Pease, History of New Bedford (1861); Leonard Bolles Ellis, History of New Bedford and Its Vicinity, 1602-1892 (1892); Conrad Reno, “Thomas Dawes Eliot” in Memoirs of the judiciary and the bar of New England for the nineteenth century (1883); Duane Hamilton Hurd, ed., History of Bristol County, Massachusetts, with biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men (1883); and in the Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress. Information on the extended Eliot family can be found in Earl K. Holt, William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical (2011) and Cynthia Grant Tucker No Silent Witness: The Eliot Parsonage Women and Their Unitarian World (2010). Also of interest, the U. S. Supreme Court trial record, Hetty H. Greene & Edward H. Greene vs. Thomas Mandell (1868).

Article by Richard Kellaway

Posted January 1, 2016