Thomas Gibson (September 5, 1777-July 1, 1863) and his only surviving son Thomas Field Gibson (March 3, 1803-December 12, 1889) were prominent silk manufacturers in Spitalfields, in London’s East End, during the industrial revolution. Developing keen interest and influence in political, economic, industrial, and social reform they developed programs to support working people through useful education, improved living conditions, and pastoral care. Some are still in operation in 2017. As Unitarian lay leaders for over half a century, they were instrumental in expanding religious liberty in England. An avid fossil-hunter and geologist, Gibson Jr. is also remembered for his work in palaeontology.

Thomas Gibson (September 5, 1777-July 1, 1863) and his only surviving son Thomas Field Gibson (March 3, 1803-December 12, 1889) were prominent silk manufacturers in Spitalfields, in London’s East End, during the industrial revolution. Developing keen interest and influence in political, economic, industrial, and social reform they developed programs to support working people through useful education, improved living conditions, and pastoral care. Some are still in operation in 2017. As Unitarian lay leaders for over half a century, they were instrumental in expanding religious liberty in England. An avid fossil-hunter and geologist, Gibson Jr. is also remembered for his work in palaeontology.

His forebears having come south from Scotland via the Lake District, Thomas Sr. was born near London to another Thomas, a laceman, and Bithiah née Mico. He became a linen draper and, like his father, a freeman of the Clothworkers’ Company. After his marriage at age 22 to Charlotte Field (who was Sir Francis Ronalds’ aunt), he entered into partnership with her brother-in-law William Venning as silk manufacturers. All were living in Islington, a little north of the City, when Thomas Jr. was born at 2 Canonbury Place.

Thomas Jr. attended the schools of Unitarian ministers John Potticary in Blackheath and probably James Tayler in Nottingham before being admitted to the Weavers’ Company in 1827. His first wife Mary Anne, daughter of physician Samuel Pett, died a week after giving birth to his only child in 1837. The next year he married Eliza Cogan, a close family friend who had assisted the delivery of her new step-daughter Mary Anne. Late in life she printed a short book Recollections of my Youth, Written at the Request of my Daughter. It described her father Eliezer Cogan’s renowned school.

The lives of father and son were always intertwined. Unitarian diarist Henry Crabb Robinson denoted them as “the Gibsons”. Having the same interests, they not only conducted business together, but also shared community activities and social engagements. Home life was similar. The whole family moved from Hanger Lane, Tottenham, to Elm House, Walthamstow – close to the Cogans – after Gibson Jr.’s second marriage. By 1850 they were back in London, living between Hyde Park and Regent’s Park: Gibson Sr. in Clarence Terrace and Gibson Jr. in Westbourne Terrace. Their silk house was initially in the City and later in Spital Square.

There were some differences. Both were “studious”, “logical”, “independent and consequential thinkers”, but the father more “philosophical” and the son more “prudent”. Contributing to public bodies, Gibson Jr. was “actively useful” but “unobtrusive” – “doing that real business without which nothing effective could have been accomplished” but avoiding the limelight. His father, in contrast, combined “a commanding form” with “vivid” “power of narrative”, and his “strongly-marked character” exhibited “manly force and fearlessness”. They would have complemented each other well at work and play.

Their trade – silk – was the fabric of the rich and British silk was woven in Spitalfields. Yet the high-profile industry was already suffering volatility and periods of distress when Gibson Sr. entered it. The market fluctuated with the caprice of fashion, international supply challenges and changing economic factors. High import duties and prohibition helped to protect the sector but also encouraged smuggling into Britain of the much-admired French silks. Manufacturing began to move to country areas where labour was cheaper and soon steam power and the factory system would threaten the traditional cottage industry in Spitalfields. Suffering cycles of poverty, weavers employed collective action and occasional violence in their appeals for better conditions. An 1851 article “Spitalfields” in Household Words, Charles Dickens’ weekly journal, provided readers with an overview of the silk trade and its problems.

It was a large and geographically dispersed business. Silk was imported either raw or thrown (twisted and combined to form the warp and weft). After preparation including cleaning, dying and making the pattern, a selected fabric was woven for sale in domestic or international markets. Gibson Jr. spent time in Lombardy studying how raw silk was produced and in 1822 they partnered in building the Depot Mill in Derby and employed up to 300 throwsters. Their prepared silk was put out to several hundred weaving families with handlooms in their homes in London and also in Halstead, Essex, and they retained this approach despite increasing mechanisation of the weaving sector.

Gibson Sr., according to the editor of the London Morning Chronicle, was “one of the most liberal, intelligent and respectable” of the silk manufacturers and, despite some early financial problems with Venning, he grew to become one of the largest. He and his son were industrialists, first and foremost, but like numerous other Unitarians of the period, the personal satisfaction and financial achievement they worked towards was mirrored in aid to those less fortunate. While Gibson Jr. (and his father before him) was “liberal… with his time, his ripe experience, and his purse” across various worthy causes, the business itself was run on a purely commercial basis – in Gibson Sr.’s words: “I never had a Weaver who earned a large Sum of Money but that my Profit was always commensurate to his”. They maximised profit (and wages) by influencing government thinking, optimising operations and adjusting nimbly to new commercial realities.

Their close friendships with Whig politicians helped them shape public policy, as illustrated in surviving letters. Gibson Sr. had a “profound” understanding of economics and was an early believer in laissez-faire capitalism. When he entered business, details of how different pieces were to be woven and corresponding pay rates were regulated in Spitalfields, which in his view jeopardised quality and precluded flexibility and innovation. As he argued at a Government select committee in 1818, the legislation “is destructive of ingenuity”; “the weaver is paid by the quantity of work which he performs, but the master is paid by the ingenuity with which the weaver puts the work together, and… the law… prevents that remuneration”.

He played an active role in the repeal of the Spitalfields Acts in 1824 and the result for their firm was recorded by the 1840 Commission on Hand-loom Weavers: artisans agreed that Gibson Jr. gave them “a price above many of the Spitalfields manufacturers” and “so arranged his business, that they had but very little play [waiting for materials and]… consequently… would earn more”. It also described how his weavers had “all formed into a… benefit society” for mutual support and that any potential new member was vetted by them. This was of as much value to Gibson Jr. as the artisans, as he suffered negligible loss of valuable silk and cash advanced to the workers and they “made goods of the best description”.

The Gibsons supported the complete removal of commercial protectionism over time through the reduction of import duties on raw materials and even on finished silk – as long as tariffs on other goods were also lowered to make the cost of living cheaper. This would increase the market for luxury items through great affordability. It would also bring strong foreign competition as France was the acknowledged leader in silk manufacture and fashion, but Gibson Jr. explained to the Government that this would encourage improvements in the local industry.

In common with other Unitarians, the Gibsons saw the key to a better society as being education. For their trade, practical education was also central to improved product quality, which was now imperative to compete with the cheaper provincial silks and more beautiful French ones. In an early effort to promote enhancements in equipment and skills, Gibson Sr. was the founding President of the Spitalfields Mechanics’ Institution, which was opened when the restrictive Spitalfields Acts were repealed (and just a year after the main institution in central London was launched). Managed by a committee of which two-thirds were artisans, there were regular lectures and a library and reading room. Gibson Sr. hoped that it would “have the effect of uniting two classes hitherto separated, viz. the employers and the employed” but it was not a success. Large numbers of weavers joined up but attendance petered off before long as the 8 p.m. lectures curtailed their working day. The final straw was apparently a talk on the steam engine that aroused “a fear of their trade being injured by machinery”. The organisation morphed into the Eastern Literary and Scientific Institution of which Gibson Jr. was still patron 20 years later.

This was an era when it was virtually unknown to have public displays of recent innovations. To address this, in 1828 the “National Repository for the Exhibition of Specimens of New & Improved Productions of the Artisans and Manufacturers of the United Kingdom” was established. Its goal in modern language was to stimulate best practice and ideas-sharing through an annual showcase of the latest wares. Gibson Sr. took responsibility in the important area of textiles and liaised with regional manufacturing centres to select specimens. Spitalfields also featured, with silk looms at work and their products on view. Unfortunately, with the concept being new, there were numerous detractors in the press and the repository closed after about five years.

A specific concern for the Gibsons was that London weavers held a less prominent position in their industry than their counterparts in France. French craftsmen had “taste and skill” which, together with their newer tools of trade, enabled them to bring more artistry to their work and “produce the pattern to the manufacturer”. It was the other way round in Spitalfields, where the manufacturer first engaged a designer (on good pay) to create the pattern to be woven. More generally, British manufacturing was seen to lead in efficiency but lag in style.

The Government appointed a select committee in 1835 to explore “the best means of extending a knowledge of the arts and of the principles of design” in “the manufacturing population”. Like other industrialists, Gibson Jr. called for training, “coupled with the protection of patterns”. Copyright law for registered designs was passed in 1839. The Government School of Design began operations in 1837 and Gibson Jr. served on its council through the decade of its existence in that form. The new school struggled to find its feet, there being much confusion as to how its goal should be achieved, but it survives today as the Royal College of Art (RCA).

Very soon, Gibson Jr. proposed to the council that a branch be opened in Spitalfields. He served on its committee of management too and participated in the annual prize-giving ceremonies of both schools. Numerous weavers sent their children to the evening classes at the Spitalfields School of Design and there were quickly positive reports of their progress. Further affiliated schools followed in the manufacturing towns to create a national system and many still exist as higher education institutes.

Another aspect of protectionism, the inflated cost of food, could be addressed by rescinding the Corn Laws, which stipulated taxes on imported grains to shield British landholders. Gibson Jr. was on the founding committee of the Anti-Corn Law Association in London in 1836 and was one of a small deputation representing London interests that met in early 1839 with Richard Cobden in Manchester at the formation of the national Anti-Corn Law League. After extensive campaigning, the laws were repealed in 1846. Gibson Jr. also apparently assisted Cobden in Paris in 1860 when he was finalising negotiations for a commercial treaty with France that reduced import duties still further. Their friendship had continued, and another of their shared interests was religious education in schools.

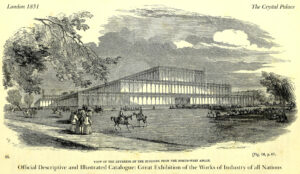

To further foster the continuous improvement required in the new era of global trade, Prince Albert conceived a “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations”. It was staged in 1851 at the Crystal Palace and Gibson Jr. was invited to be one of his Royal Commissioners. Discussing how to overcome an objection raised in Parliament concerning the event, Gibson Jr. recorded former Prime Minister Robert Peel’s advice: “Depend upon it, the House of Commons is a timid body”. Peel died three days later.

To further foster the continuous improvement required in the new era of global trade, Prince Albert conceived a “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations”. It was staged in 1851 at the Crystal Palace and Gibson Jr. was invited to be one of his Royal Commissioners. Discussing how to overcome an objection raised in Parliament concerning the event, Gibson Jr. recorded former Prime Minister Robert Peel’s advice: “Depend upon it, the House of Commons is a timid body”. Peel died three days later.

The Spitalfields weavers, although reluctant initially to be compared publically with their long-standing French rivals, agreed to participate and provided a very credible display. A specimen designed and woven by students at the Spitalfields School of Design was awarded a prize medal. Other samples they entered are still held at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A).

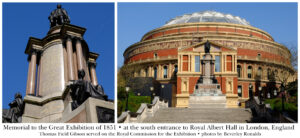

The Commissioners’ role was perpetuated after the event. An early priority was to establish a large precinct in South Kensington to “extend the influence of Science and Art upon Productive Industry” through two vehicles: practical education and display. The approaches that were so novel when Gibson Sr. first attempted them were now in the mainstream. Institutions built there include the aforementioned RCA and V&A. There is also a monument to Prince Albert and the Great Exhibition, the unveiling of which was attended by Gibson Jr. in 1863.

Not surprisingly, Gibson Jr.’s first concern with the new precinct was for the industrial districts and he had immediately advised Earl Granville that “it is scarcely possible to overestimate the importance of securing the active and hearty cooperation of the great manufacturing towns as a main element in the successful prosecution of the plan” which “may in many cases be best effected in the localities where these operations are carried on… [I]n the establishment of the School of Design… no sooner did we proceed to the establishment of Provincial Schools than a new life was infused”. Gibson Jr. remained a Royal Commissioner for the rest of his life and participated as an organiser and juror in subsequent international exhibitions in Paris and London until he was in his seventies. He was reportedly awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur for his contributions to the 1855 Exposition Universelle.

The Gibsons’ care for local communities extended to other issues. In 1832, when Unitarians established a mission in London, they chose Spicer Street in Spitalfields for its location. In addition to a chapel, Sunday school and pastoral visits to those in need, the mission was soon running day and evening schools, adult education, a library, savings bank and benevolent fund. The local Church of England minister described it in 1858 as “rather influential, I am sorry to say”. The year Gibson Jr. died, the mission moved to nearby Mansford Street where it survives today in modern form. He had served as treasurer of other charity schools in the area as well.

The Gibsons’ care for local communities extended to other issues. In 1832, when Unitarians established a mission in London, they chose Spicer Street in Spitalfields for its location. In addition to a chapel, Sunday school and pastoral visits to those in need, the mission was soon running day and evening schools, adult education, a library, savings bank and benevolent fund. The local Church of England minister described it in 1858 as “rather influential, I am sorry to say”. The year Gibson Jr. died, the mission moved to nearby Mansford Street where it survives today in modern form. He had served as treasurer of other charity schools in the area as well.

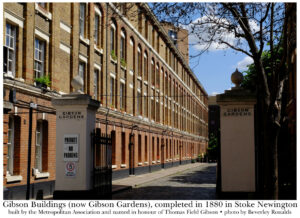

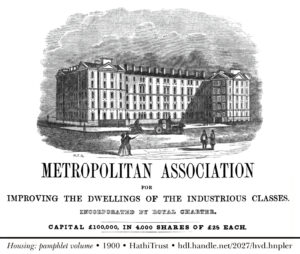

Gibson Jr. was also a founding director of the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes, having joined the provisional committee in 1843. This was perhaps the first housing association, established to build affordable rental accommodation while earning (limited) interest for the financiers, thereby encouraging ongoing investment for further schemes. The Metropolitan Association’s second project was at Spicer Street, Spitalfields. It was open for viewing as part of the Great Exhibition and the Association was awarded a gold medal at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Several of the Spitalfields buildings are now listed by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for their special interest. Gibson Buildings (now Gibson Gardens), which was completed by the Association in 1880 in Stoke Newington and named in honour of Gibson Jr.’s extended contributions, also continues today.

Gibson Jr. was also a founding director of the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes, having joined the provisional committee in 1843. This was perhaps the first housing association, established to build affordable rental accommodation while earning (limited) interest for the financiers, thereby encouraging ongoing investment for further schemes. The Metropolitan Association’s second project was at Spicer Street, Spitalfields. It was open for viewing as part of the Great Exhibition and the Association was awarded a gold medal at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Several of the Spitalfields buildings are now listed by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for their special interest. Gibson Buildings (now Gibson Gardens), which was completed by the Association in 1880 in Stoke Newington and named in honour of Gibson Jr.’s extended contributions, also continues today.

Amenities in the original developments included a reading room and library, modern plumbing, good light and ventilation, and clean linen. Subsequent studies showed the mortality rate for tenants to be much below London’s average. The Gibsons’ friend Thomas Southwood Smith, a Unitarian physician remembered for his pioneering work in public health, spearheaded this emphasis. Smith had been one of Gibson Sr.’s vice-presidents at the Spitalfields Mechanics’ Institution and he and Gibson Jr. also both served on the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers that oversaw the early work of engineer Joseph Bazalgette towards an integrated sewerage and drainage system across London.

Gibson Sr., in turn, was chairman in Tottenham of the new Poor Law Union established to administer relief to the needy poor, which he conducted with much “delicacy of feeling”. He was also a magistrate.

Gibson Sr. was born into a Calvinist family, but found Unitarianism as a teenager through the sermons and lectures of Joseph Priestley at the Gravel Pit chapel, and later studied the religious writings of Andrews Norton amongst many others. He strongly upheld his faith – often considered “the obnoxious part of the Dissenters” in his words – having been born early enough to experience the Unitarian persecution of the eighteenth century. He and his son were inclined “to the Broad Church views”, advocating “perfect freedom of conscience” and a personal, benevolent God. Discussing the pardoning of sins with Congregational theologian John Pye-Smith in the 1825 Monthly Repository, he wrote of the “most delightful feelings… towards the great and bountiful Creator… I feel the highest moral certainty that every thing is from God and of God, and that God is Love… ultimately, all will be well with every creature he has destined for immortality”.

Through much of their lives, the Gibsons actively shaped Unitarian matters in Britain, supporting various ministers as close friends and presiding over several noteworthy meetings. Gibson Sr. served on the committee that successfully lobbied parliament in 1828 for the abolition of the Sacramental Test that prevented Dissenters from holding public office. Speaking on its success, he urged all “to persevere in their exertions in favour of religious liberty, and never submit… Every man… had the opportunity to do something… in aid of this great cause”. He was also on the Committee of Dissenting Deputies (established to protect the civil rights of Nonconformists) in 1832 when it assisted in the Reform Act that made the electoral system more representative of the people. He was a founding member of the Reform Club established not long afterwards to promote further change.

In 1834, when there was talk of removing the requirement for marriages to be performed by the Church of England and some Dissenters were contemplating the controversial idea of calling publically for the separation of Church and State in Britain, he was clear in his views for the Unitarian body: “Formerly this Association… acted on principle, and never on expediency… He would insure the Treasurer’s purse from any injury… What! should it be said of them that they were afraid to declare their purposes?… Was it not that alliance which enabled a Trinitarian Episcopalian Church continually to rob them of their property, and to expose them to the degraded situation of a tolerated sect?” Civil marriage became legal two years later. Still active in his late seventies, he had witnessed further religious toleration and was pleased to be able to remind others that “sixty years ago… there was no anticipation whatever… of the success which we have seen”.

As the joint executors for Thomas Belsham, minister of the Essex Street chapel, the Gibsons rescued valuable correspondence between Joseph Priestley and Theophilus Lindsey that informed a biography of the former. Gibson Sr. also gave “zealous support” to Robert Aspland of the Gravel Pit chapel in his initiatives. For some years he aided the popular minister William Johnson Fox at South Place but, being treasurer, was the recipient of Fox’s letter of resignation on July 26, 1834 after they met at his home. Gibson Sr. also chaired the chapel committee’s meeting that accepted the resignation, precipitating Fox’s removal from the Presbyterian body of ministers. It was about to become public that Fox had separated from his wife and developed a close relationship with his ward Eliza Flower. The Gibsons were one of the families who chose to leave South Place at this time.

Other committee work included being a prime mover at the Unitarian Book Society which printed gospel texts, Gibson Sr. having joined the Society in 1802, and he was an original committeeman of the Christian Tract Society formed in 1809 to distribute books with a moral message to the poor. He was also a trustee of the Unitarian Fund that supported missionary work, and a foundation committee member of the Association for the Protection of the Civil Rights of Unitarians established in 1819.

He then chaired the milestone meeting on May 26, 1825 at which the British and Foreign Unitarian Association (BFUA) was formed – there was now national coordination across Unitarian matters for the first time through the merging of the earlier entities. Gibson Sr. was an early treasurer of the new Association and he and his son both presided at the annual meeting at various times.

From 1813, Gibson Sr. had supported Aspland as secretary of his new Unitarian Academy at Hackney. It had the goal of training popular preachers for missionary work, but was short lived. He later chaired the foundation meeting on January 14, 1835 of the London Domestic Mission Society, which was established with the expectation that a local entity distinct from the BFUA would be better able to support the new Spitalfields mission and others to follow. Both father and son became life members, Gibson Jr. served on the committee for many years, and a century later his family was still “the most devoted supporters, both financially and by personal service” of the missions.

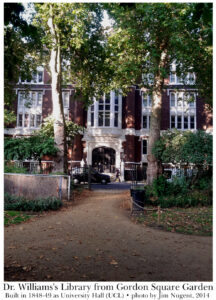

Gibson Jr. was also prominent at University College (now UCL), the first secular University in England. Sitting on the council for nearly 20 years, he and others tried – unsuccessfully – to appoint James Martineau to the Chair of Mental Philosophy and Logic. He also served on the University College Hospital committee, to which his final donation was a £500 bequest in his will. He was a founding member of the committee that built University Hall as a memorial to the passing of the Dissenters’ Chapels Act in 1844 (which gave Unitarians future security over their long-held places of worship) and is now the home of Dr Williams’s Library. The Gibsons additionally helped lead various charities with Unitarian links, including the Hibbert Trust that supported Nonconformist scholarship and the New England Company that funded missionary work in the Americas.

Gibson Jr. was also prominent at University College (now UCL), the first secular University in England. Sitting on the council for nearly 20 years, he and others tried – unsuccessfully – to appoint James Martineau to the Chair of Mental Philosophy and Logic. He also served on the University College Hospital committee, to which his final donation was a £500 bequest in his will. He was a founding member of the committee that built University Hall as a memorial to the passing of the Dissenters’ Chapels Act in 1844 (which gave Unitarians future security over their long-held places of worship) and is now the home of Dr Williams’s Library. The Gibsons additionally helped lead various charities with Unitarian links, including the Hibbert Trust that supported Nonconformist scholarship and the New England Company that funded missionary work in the Americas.

From the early 1840s, the Gibsons invested significantly on the Isle of Wight, including a seaside home at Sandown. There Gibson Jr. was able to indulge his love of fossil-hunting and his house became “a frequent meeting-place of geologists”. He was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society of London in 1847 and served on its council.

In 1856-7 he found the type specimen of an extinct plant species that had worldwide distribution in the Mesozoic period. He arranged for it to be examined with Dr Joseph Dalton Hooker, director of the Kew Gardens, and John Morris, professor of geology at University College, who split it apart for closer scrutiny. Pods with seeds were found attached to the trunk. He later donated one of the blocks to Kew and other parts to what is now the Natural History Museum, where it was first categorised by William Carruthers and named Bennettites Gibsonianus after the finder. Thin sections made through the sample also survive in the Manchester Museum and elsewhere. A number of detailed drawings have been published. Gibson Jr. later admitted to Carruthers his regret “that I did not have the whole fossil divided and polished, and that I allowed it to be broken up”. In the 21st century the specimen has been reiterated to be “really of enormous historical significance”.

He also published a paper in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London (1858) describing his discovery of a fossilised femur of the Iguanodon dinosaur near Sandown. It was believed to be the largest yet recorded, being nearly 1.5 m long and 35 cm in diameter at its narrowest point.

Once his parents had passed away, both at age 85, Thomas Jr. and Eliza left London for Royal Tunbridge Wells and their newly-built residence at 10 Broadwater Down. Again he threw himself into community affairs, supporting various societies and serving on the town’s Local Board responsible for roads, water supply, drainage and the like. Not long before they both died – seven months apart – the couple moved once more to Hampstead, north London, to be close to daughter Mary Anne and her family. There they attended their friend Thomas Sadler’s service at Rosslyn Hill chapel in the twilight of their long lives.

The Gibsons’ words are found in government reports, Unitarian periodicals, newspapers and magazines. Their letters survive at Conway Hall Ethical Society; the Archive of the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 at Imperial College (ref. RC/A/1851/781); the British Library; the Institution of Engineering and Technology; and the Natural History Museum (ref. DF BOT/404/1/3/65), all in London; as well as Manchester Central Library, Archives & Local History; and the East and West Sussex Record Offices. Minutes of meeting and annual reports relating to their community activities are in Conway Hall, the London Metropolitan Archives, Dr Williams’s Library, Royal Society of Arts (RSA), and UCL, and others have been printed.

There are obituaries in The Inquirer (1863 and 1889), Christian Reformer (1863), Christian Life and Unitarian Herald (1889), Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London (1891), Records of the Manor, Parish, and Borough of Hampstead (1890) and several national newspapers. Further information is given in parish histories and the family appears in the published memoirs of Sir Henry Cole, Thomas Belsham, Edwin Wilkins Field (a distant cousin), Samuel Sharpe, Henry Solly, Robert Aspland and Henry Crabb Robinson. Gibson Jr. is listed on the memorial to the Great Exhibition in South Kensington. His only known image is in Henry Courtenay Selous’ painting of the Exhibition’s opening ceremony, where the quite indistinct depiction suggests that he was one of the Royal Commissioners who did not attend a sitting with the artist. The Whig view of the Spitalfields weaving trade in the period is illustrated in Harriet Martineau’s The Loom and the Lugger (1833), while Fighting Words: Working-Class Formation, Collective Action, and Discourse in Early Nineteenth-Century England (1999) by Marc Steinberg gives a more modern take on the workers’ perspective.

Article by Beverley F. Ronalds

Posted November 12, 2017