Owen Glenbrook Hansen (September 24, 1923-August 30, 2006) was born into a family with a strong tradition of independent thought: Pacifism and freethought on his father’s side; Unitarianism and vegetarianism on his mother’s. Raised on a farm in rural New Zealand during the Great Depression, he became proficient in a broad range of agricultural and mechanical pursuits. His elder brothers started a commune on one of the family farms; as avid apiarists they called their intentional community Beeville. After Hansen refused military service during World War II, he was confined in internment camps and prison for the duration of the war. The radical Hansen mellowed in the last half of his life to become a regular fixture at gatherings of New Zealand Unitarians, a group that still numbered less than 500 people in a country of 3.8 million in 2001.

Owen Glenbrook Hansen (September 24, 1923-August 30, 2006) was born into a family with a strong tradition of independent thought: Pacifism and freethought on his father’s side; Unitarianism and vegetarianism on his mother’s. Raised on a farm in rural New Zealand during the Great Depression, he became proficient in a broad range of agricultural and mechanical pursuits. His elder brothers started a commune on one of the family farms; as avid apiarists they called their intentional community Beeville. After Hansen refused military service during World War II, he was confined in internment camps and prison for the duration of the war. The radical Hansen mellowed in the last half of his life to become a regular fixture at gatherings of New Zealand Unitarians, a group that still numbered less than 500 people in a country of 3.8 million in 2001.

Hansen’s mother, Amy Mildred Causley Hansen had grown up in Auckland, New Zealand where she was active in the Auckland Unitarian Church, the first one in the country. She attended when William Jellie (1865-1963), the first minister arrived in 1900. The next year she left Auckland and moved to Thames but remained involved in church activities through her extensive correspondence with Unitarian women.

Owen Hansen’s father, Waldemar Hansen was a free thinker and pacifist. His paternal grandfather Johnan had left Denmark, with his brother Lars, in 1857 to avoid military conscription. At the time, they thought war with Prussia was imminent. They arrived from Australia in 1861 and went to Thames, New Zealand where they were successful general merchants. The Thames area was growing rapidly after gold was discovered in 1867. It was in Thames where William Jellie, the minister at the Auckland Unitarian Church officiated at the 1904 marriage of Amy Mildred Causley and Waldemar Hansen. As a youngster Owen was well aware of his mother’s Unitarianism. In his Diary he recorded a family visit to the Auckland Unitarian Church in 1931, and how they met the husband and wife co-ministers Wilna and William Constable. Later that year he records listening on the radio to an evening service from the Unitarian Church.

Owen Hansen was the youngest of nine children; he had eight brothers and one sister. When he was born the family was living in the Waikato region on a farm near Orini, New Zealand. Following his primary school education, he attended Hamilton Technical High School for one year, taking the builders course. He had a natural aptitude for mechanical work—he repaired trucks and cars on the farm—which he attributed to watching his father and brothers. When he was 15, he developed an interest in radio. Studying books, he soon learned how to build and repair them. He took a correspondence course in radio and electrical theory from Druleigh College in Auckland and later learned television servicing through night classes at the Waikato Technical Institute. He also was proficient at mechanical design, mechanical repairs, welding, plumbing, home design, and building construction. But these skills came later; first Owen was to work on the family farms.

From the age of 15 Hansen worked with a brother who was a beekeeper; he then returned home and managed the small home farm singlehanded, and also worked for another brother with a farm contracting business; cultivating, hay-mowing, and baling. This work experience within the family produced a competent agriculturalist, orchardist, horticulturalist and market gardener at a relatively young age.

His family was vegetarian; his mother from her early days and his father after an illness. While their vegetarianism had sometimes resulted in ridicule at school, the animal rights aspect as well as the personal health aspect of this philosophy was increasingly recognised and accepted in New Zealand. Hansen thought that, “. . . vegetarianism is the belief that you shouldn’t kill animals unnecessarily. In a way this consideration for others is similar with Christian values of life.” In the 1930s, during the inter-war period, pacifism and vegetarianism were closely allied; both philosophies recognizing the unity of life, be it human or animal.

In 1942 Hansen was called up for military service. After passing the medical examination, he decided to not report for duty at Hamilton, New Zealand. He applied for exemption from military service on the grounds that he was a conscientious objector, but it was denied, and he was ordered to report for non-combatant service in the medical corp. When he failed to report for non-combatant medical duty, he was sentenced to confinement in a detention camp for the remainder of the war.

In 1942 Hansen was called up for military service. After passing the medical examination, he decided to not report for duty at Hamilton, New Zealand. He applied for exemption from military service on the grounds that he was a conscientious objector, but it was denied, and he was ordered to report for non-combatant service in the medical corp. When he failed to report for non-combatant medical duty, he was sentenced to confinement in a detention camp for the remainder of the war.

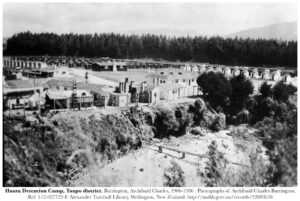

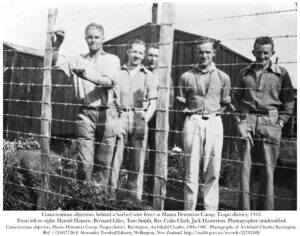

During World War II there were 13 detention camps in New Zealand containing 803 men. Books were censored, visitors limited (even if they could get to the isolated locations), mail was censored; there were checks, roll calls, and rules to stop men from congregating. The inmates wore borstal grey uniforms and blue denim for work. Penalties could be inflicted at the discretion of the guards (unlike regular prisons), and boundaries and barbed wire surrounded the camps. Hansen spent time at the Strathmore, Piaka, Ohio, and Hautu camps.

The Strathmore Camp, south of Rotorua was the largest detention camp with 300 detainees. While there he wrote to the Secretary of the Armed Forces Appeal Board in 1942 explaining his position as a pacifist:

From an early age it has been my belief that the solution to the problem of settling our differences could not be found in the use of physical force. At school I avoided becoming involved in fights. We were also taught there that the highest aim of a man was to live in a true and conscientious manner.

I myself do not belong to any set religion, but my mother belongs to the Unitarian Church whose religion is based on free thought. As a result we were brought up to think for ourselves. This I have done and am strong in my convictions that war is against the principles of Truth and cannot bring Peace.

My sympathies lie with the people of the world as a whole rather than with any one nation. I consider that we are all God’s people and He is in each and every one of us and therefore I could not take it upon myself to harm or in any way assist in doing so to one or any of our Human Brotherhood. This also confirms with my understanding of the teachings of all the Great World Teachers including Jesus the Christ.

Conditions at the detention camps varied. Inmates were usually given four blankets with an extra blanket in winter; there were no mattresses. Men worked in gangs digging drains, cutting scrub, farming, and producing food for themselves. For the vegetarian prisoners, it was a struggle to obtain sufficient food to eat. Workers Educational Association courses could be taken, and they had access to books; Hansen estimated that he read about 150 books during his detention. Five of his seven brothers were also deemed fit for military service, and they also ended up spending time in detention camps.

For the young Hansen it was hard not seeing his older brothers. When the opportunity occurred to see Harold who was held in a nearby compound, Owen broke the rules trying to see him. For that he was sentenced to three months jail for refusing to obey when ordered to return to his compound. During 1944 he was sent to Rangipo Prison with other defaulters who refused to work until they were given a rehearing of their appeals. He was held in solitary confinement for four months, during which time he lost two stone (28 pounds) and his sight failed from poor food, lack of light, and lack of exercise. “The blankets were hard and thin. Some had holes in them,” he later recalled. “To try and stay warm, I doubled them up, but there was a monstrous gap under the door, and when a freezing southerly whistled straight in [I] somehow shivered my way to sleep about five o’clock…we had to be up at six.”

For the young Hansen it was hard not seeing his older brothers. When the opportunity occurred to see Harold who was held in a nearby compound, Owen broke the rules trying to see him. For that he was sentenced to three months jail for refusing to obey when ordered to return to his compound. During 1944 he was sent to Rangipo Prison with other defaulters who refused to work until they were given a rehearing of their appeals. He was held in solitary confinement for four months, during which time he lost two stone (28 pounds) and his sight failed from poor food, lack of light, and lack of exercise. “The blankets were hard and thin. Some had holes in them,” he later recalled. “To try and stay warm, I doubled them up, but there was a monstrous gap under the door, and when a freezing southerly whistled straight in [I] somehow shivered my way to sleep about five o’clock…we had to be up at six.”

Hansen was released in May 1946, a year after the war in Europe ended and nine months after the Pacific war ended. He had served three and a half years, including four months solitary confinement with 52 days on bread and water punishment. His brother Harold had been in for almost four years.

After his release, he spent 18 months living at Beeville, the New Zealand utopian community that had been established by his brothers Ray and Dan in 1933. The 50 acre property, originally part of a dairy farm had been transformed into a rural haven with the planting of hedges, orchards, trees, and gardens. In addition to harvesting and selling honey, the commune grew corn, potatoes, watermelons, pumpkins and other crops. The houses, workshop buildings, and swimming pool were built by community members. Beeville had been founded on utopian principles during the Great Depression and was intended to provide a beacon of hope in a world that needed–in the eyes of its founders–to build a new co-operative society. It has been said that at times, “Beeville seems more like the story of one remarkable family than the story of an unusual experiment in communal living, but it is clearly both.” During the 1940’s and 1950’s Ray sent reports about Beeville’s support for pacifism to The Word, a publication of the United Socialist Movement in Glasgow, Scotland. This brought Beeville to the attention of a much wider audience.

People were free to stay at Beeville and were expected to work in return. There was no hierarchy of power or authority, it was expected that decisions would be reached by broad consent. The orchards and gardens provided food for the members while honey production, roadside sales of produce, and the farm contracting and machinery repair businesses provided cash income.

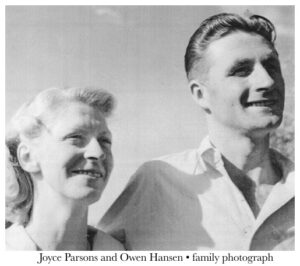

In 1950 Hansen met Joyce Parsons, who became his partner for life. Joyce had three girls from a previous marriage and would have six children with him, two daughters and four sons, including twin boys. They lived in Orini, in the same house where he had been raised. Over the years, he redesigned and rebuilt it. He ran his rural electrical and mechanical repair business from the family farmstead. He was active in the Labour Party, and he wrote letters for the correspondence columns of local newspapers to spread his views on economic and political issues. He also joined his older brothers in poetry writing, although in his case the poems were always political with the then Prime Minister of New Zealand as the preferred target. He joined the World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms (WWOOF) movement, which allowed people, especially overseas visitors, to stay and work on organic farms. His farm comprised five hectares of garden, orchard, grapes, and kiwifruit with some cattle. Visitors were advised to “accept responsibility for their actions, accept advice and gentle criticism… contribute towards the upkeep and income of the place… [or] contribute towards the running expenses or leave… Only nutritious vegetarian food provided. No smoking or drugs.”

It was in the 1960’s that Hansen began taking a deeper interest in the Auckland Unitarian Church, making the long drive from Orini to Auckland on a Sunday morning. He would be seen three or four times a year and formed friendships with a number of its members and enjoyed the fellowship. Hansen continued his visits to the Auckland church over the next forty years, frequently in the company of one or more of the visitors staying on his farm. He continued to enjoy good health and an active and energetic life, fitting in a busy work day with his literary and political interests. He died following a very short illness in 2006. Joyce had died in 2000. His family arranged for his life to be celebrated in a civil service at the Gordonton Hall in a pleasant village not far from his home. The chairman of the Auckland Unitarian Church attended.

It was in the 1960’s that Hansen began taking a deeper interest in the Auckland Unitarian Church, making the long drive from Orini to Auckland on a Sunday morning. He would be seen three or four times a year and formed friendships with a number of its members and enjoyed the fellowship. Hansen continued his visits to the Auckland church over the next forty years, frequently in the company of one or more of the visitors staying on his farm. He continued to enjoy good health and an active and energetic life, fitting in a busy work day with his literary and political interests. He died following a very short illness in 2006. Joyce had died in 2000. His family arranged for his life to be celebrated in a civil service at the Gordonton Hall in a pleasant village not far from his home. The chairman of the Auckland Unitarian Church attended.

Owen Hansen’s Diary for 1931 is held by his son Paul Hansen. Archives New Zealand in Wellington, New Zealand holds correspondence by the Hansen brothers regarding the “Beeville Community” while the Auckland War Memorial Museum in Auckland, New Zealand has a collection of his mother’s letters to Unitarian women. Two manuscripts by Owen Hansen, Cause of New Zealand’s Present Economic Plight (undated) and Statements, Candidates Speeches, etc. for the Waikato Branch of the N.Z. Values Party (abt. 1972) can be found in the Hamilton City Libraries in Hamilton, New Zealand. The Hamilton Library also has a copy of a book by Owen Hansen, Political Poems and Comment (undated). An audio interview with his brother Ray Hansen is available on-line at TEARA: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

Judith Simpson and Katherine Knight, The Hastie Hansen Story: Irish and Danish Family Links, (1995) has chapters on the Hansen family in Denmark and the Hansen brother’s time in Thames while Lucy Sargisson and Lyman Tower Sargent, Living in Utopia: New Zealand’s Intentional Communities (2004) has a chapter on Beeville. Catherine Amey, The Compassionate Contrarians A history of vegetarians in Aotearoa New Zealand, (2014), has a chapter on Beeville and the Hansen brother’s incarceration as conscientious objectors, and provides an extensive history of New Zealand vegetarianism (pdf). The lives of the Hansen brothers are also covered in David Grant, Out in the Cold: Pacifists and Conscientious Objectors in New Zealand during World War II (1986).

A short article based on an extensive interview with Owen about his experience as a vegetarian and a pacifist is found in Keith Lyons article, “Daring to be Oneself” in Vegetarian Lifestyle (1990). Also useful are the November 1946 and July 1959 issues of The Word, published in Glasgow, Scotland by Guy Aldred. They contain letters from Ray Hansen. In the 1940s, The Word, which carried Methodist, Baptist, Quaker, Unitarian, Secular, and Socialist items from around the world, invited its readers to “. . . a feast of thought, truth, and discussion: a world of free Thought and free gathering of humanity in the spirit of Truth, Fellowship and Understanding.”

Article by Wayne Facer

Posted June, 2015