Mary Ashton Rice Livermore (December 19, 1820-May 23, 1905) was a key organizer for the United States Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. Afterwards, she became a leader of the woman suffrage and temperance movements, and a popular lecturer on social reform. Her husband, Daniel Parker Livermore (1818-1899) was a Universalist minister, a social activist, an editor, and a writer. Their lives and careers were inextricably linked from the time of their first meeting in 1843 until Daniel’s death.

Mary Ashton Rice Livermore (December 19, 1820-May 23, 1905) was a key organizer for the United States Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. Afterwards, she became a leader of the woman suffrage and temperance movements, and a popular lecturer on social reform. Her husband, Daniel Parker Livermore (1818-1899) was a Universalist minister, a social activist, an editor, and a writer. Their lives and careers were inextricably linked from the time of their first meeting in 1843 until Daniel’s death.

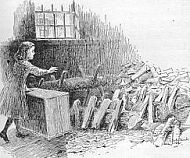

Mary Rice, born in Boston into a strict Calvinist Baptist family, took religious questions seriously as a child. She liked to pretend to be a preacher, using the kitchen table as her pulpit, and if she could find no live audience, would “go alone to the wood shed, arrange the unsplit logs in rows as pews, and the split sticks as an audience occupying them, and then mount a box, which served for a pulpit, and preach, and pray, and sing by the hour.”

Well catechized in Calvinist beliefs at an early age, she was troubled by the doctrine of predestination and became haunted by fear of death and the hereafter. At age seven or eight, she urged her parents to send her newborn sister back to God before it was too late, fearing the baby might not be among those destined for salvation. Later, as a young woman, she was plunged into deep depression by the death of another sister whom she feared might not have been among the elect. Her minister and her father, though both kind men, were unable, as committed Calvinists, to provide her any real comfort. “I had now reached a crisis in my life,” she wrote. “Happiness and I had parted company forever, unless in some certain and assured manner I could be convinced that my sister Rachel was not among the lost.”

Well catechized in Calvinist beliefs at an early age, she was troubled by the doctrine of predestination and became haunted by fear of death and the hereafter. At age seven or eight, she urged her parents to send her newborn sister back to God before it was too late, fearing the baby might not be among those destined for salvation. Later, as a young woman, she was plunged into deep depression by the death of another sister whom she feared might not have been among the elect. Her minister and her father, though both kind men, were unable, as committed Calvinists, to provide her any real comfort. “I had now reached a crisis in my life,” she wrote. “Happiness and I had parted company forever, unless in some certain and assured manner I could be convinced that my sister Rachel was not among the lost.”

Mary reexamined the Bible, even studying Greek so that she could read the New Testament in its original language, and while she found no convincing evidence to support the doctrine of eternal punishment, she lacked confidence in her findings. Finally, she sought escape from the painful associations of her surroundings by accepting a position as tutor on a slaveowner’s plantation in Virginia, where she lived for three years, c.1839-42.

Living in the South she learned that slavery was as “demoralizing and debasing” to white slaveowners as it was hard and painful for blacks. One experience in particular, witnessing the brutal whipping of a cooper named Matt, rendered her ill for days afterward. By the time she returned to New England, Mary was an ardent abolitionist.

Daniel Livermore was the youngest of nine children born to a prosperous farm family in Leicester, Massachusetts. Since his sisters were grown, Daniel grew up helping his mother in the dairy and in the kitchen. He grew up knowing more about cooking and housekeeping than most young men of his time. Daniel studied for the Universalist ministry under William S. Balch in Providence, Rhode Island. Newly admitted into fellowship, he began his career in ministry in Georgetown, Massachusetts, 1841-43, then received a call to Duxbury, Massachusetts.

On Christmas Eve in 1843, Mary Rice took a walk around Duxbury, where she served as headmistress of a school. In the midst of another theological crisis, she pondered whether life had meaning. As she passed the Universalist church she was attracted by the cheerful singing coming from within. Mary had never attended either a Christmas service or a Universalist service, the Baptists considering the former to be popish and the latter to be outside the Christian pale. Nevertheless, she entered and found herself surprised and uplifted by the message she heard. After the service she introduced herself to the church’s young minister, Daniel Livermore, and inquired where she might find some Universalist literature. With books borrowed from Daniel’s library, Mary “was soon deep in a course of theological reading and study.” William Ellery Channing‘s “Moral Argument against Calvinism” proved especially convincing to her. She met with Daniel frequently. As a result, Mary embraced Universalism and Daniel and Mary fell in love. Although friends and some members of her family disapproved, they were wed in 1845. Their strong marriage lasted for over half a century. They had three daughters, Mary, Henrietta, and Marcia Elizabeth. Mary died in childhood.

On Christmas Eve in 1843, Mary Rice took a walk around Duxbury, where she served as headmistress of a school. In the midst of another theological crisis, she pondered whether life had meaning. As she passed the Universalist church she was attracted by the cheerful singing coming from within. Mary had never attended either a Christmas service or a Universalist service, the Baptists considering the former to be popish and the latter to be outside the Christian pale. Nevertheless, she entered and found herself surprised and uplifted by the message she heard. After the service she introduced herself to the church’s young minister, Daniel Livermore, and inquired where she might find some Universalist literature. With books borrowed from Daniel’s library, Mary “was soon deep in a course of theological reading and study.” William Ellery Channing‘s “Moral Argument against Calvinism” proved especially convincing to her. She met with Daniel frequently. As a result, Mary embraced Universalism and Daniel and Mary fell in love. Although friends and some members of her family disapproved, they were wed in 1845. Their strong marriage lasted for over half a century. They had three daughters, Mary, Henrietta, and Marcia Elizabeth. Mary died in childhood.

The Livermores moved frequently during the early years of their marriage as Daniel served a succession of churches: Fall River, Massachusetts, 1845-46; Stafford Centre, Connecticut, 1846-51; Weymouth, Massachusetts, 1851-53; Malden, Massachusetts, 1853-55; and Auburn, New York, 1855-57. Daniel’s stands on slavery, women’s rights and temperance often caused tension with his parishioners. Mary, while strongly supporting her husband’s views, was unhappy with her role of minister’s wife. She found an outlet in writing and won two prizes for her stories—Thirty Years too Late, 1845, on temperance, and A Mental Transformation, 1848, about “changes wrought in one’s life and character by a vital change of religious belief.”

The Livermores moved frequently during the early years of their marriage as Daniel served a succession of churches: Fall River, Massachusetts, 1845-46; Stafford Centre, Connecticut, 1846-51; Weymouth, Massachusetts, 1851-53; Malden, Massachusetts, 1853-55; and Auburn, New York, 1855-57. Daniel’s stands on slavery, women’s rights and temperance often caused tension with his parishioners. Mary, while strongly supporting her husband’s views, was unhappy with her role of minister’s wife. She found an outlet in writing and won two prizes for her stories—Thirty Years too Late, 1845, on temperance, and A Mental Transformation, 1848, about “changes wrought in one’s life and character by a vital change of religious belief.”

In 1857, frustrated with parish life, the couple moved with their two surviving daughters to Chicago while Daniel explored the possibility of moving to Kansas to help establish an anti-slavery colony. However, the serious illness of their younger daughter, Marcia Elizabeth, caused them to abandon the plan, and they made Chicago their home for the next thirteen years. During this period Daniel bought and edited a reform-centered Universalist newspaper, the New Covenant, wrote several books on Universalist theology, helped organize the Northwestern Conference of Universalists, went on numerous preaching missions, and held several brief part-time pastorates in the area.

It was during this period that Mary, with Daniel’s help and encouragement, came into her own as a competent, self-confident woman with an important role to play in the reshaping of society. A turning point came when, during a cholera epidemic in the city, she determined to stay and volunteer her help rather than leaving Daniel and fleeing with her daughters. She quickly developed organizational skills, and when the Civil War broke out she was recruited by Henry Whitney Bellows, head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, to become co-ordinator of the Northwestern branch. During the next four years she organized a far-flung volunteer support network for the Union hospitals, visited the hospitals, wrote letters “by the thousands” for soldiers, escorted wounded soldiers from hospitals to their homes, and raised large sums of money in support of the Commission’s work.

It was during this period that Mary, with Daniel’s help and encouragement, came into her own as a competent, self-confident woman with an important role to play in the reshaping of society. A turning point came when, during a cholera epidemic in the city, she determined to stay and volunteer her help rather than leaving Daniel and fleeing with her daughters. She quickly developed organizational skills, and when the Civil War broke out she was recruited by Henry Whitney Bellows, head of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, to become co-ordinator of the Northwestern branch. During the next four years she organized a far-flung volunteer support network for the Union hospitals, visited the hospitals, wrote letters “by the thousands” for soldiers, escorted wounded soldiers from hospitals to their homes, and raised large sums of money in support of the Commission’s work.

During the war, Mary became “aware that a large portion of the nation’s work was badly done, or not done at all, because woman was not recognized as a factor in the political world. . . . [M]en and women should stand shoulder to shoulder, equal before the law.” Women, she concluded, needed the right to vote. When the war ended, Mary rose to leadership in the woman suffrage movement, writing and traveling widely as she lectured and chaired meetings. In 1868 she organized the first woman suffrage convention held in Chicago.

After the New Covenant, at which she had worked with Daniel as co-editor, had been sold, in 1869 Mary served as editor of the woman’s rights periodical, the Agitator. Later that year the Agitator was merged with the Woman’s Journal, published in Boston. In 1870 the couple moved to Melrose, Massachusetts, in order for Mary to continue her editorial work.

It was not long, however, before James Redpath, head of the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, urged her to devote full-time to lecturing. Daniel urged her to accept the invitation. “It is preposterous,” Mary remembered him as saying, “for you to continue baking and brewing, making and mending, sweeping, dusting, and laundering, when work of a better and higher order seeks you. By entering upon it, you can advance your views, make converts to the reforms with which you are identified, and openings for two or three women who can do this housework as well as you. You need not forsake your home, nor your family; only take occasional absences from them, returning fresher and more interesting because of your varied experiences.” “There was force in his manner of stating it,” she reported, “and the matter was settled.” For almost a quarter of a century, until her retirement in 1895, Mary devoted herself to this new career, speaking on women’s rights and other reform topics “in every part of the country from Maine to Santa Barbara.”

Mary Livermore’s lectures, delivered without manuscript or notes, addressed a wide variety of topics, ranging from women’s rights and temperance to immortality. While reflecting her Universalist convictions, all were crafted for broad appeal to a general audience. In “Concerning Husbands and Wives” she held up a model of marriage between equal, complementary partners. In “The Battle of Life” she shared her vision of the better world that was to come and encouraged her listeners to move in its direction. In “Does the Liquor Traffic Pay?” she described the huge social cost of alcohol and called on her audience to join her in winning the temperance battle. In “Has the Night of Death no Morning” she affirmed her belief in the soul’s immortality, a belief to be fostered by noble living. In “What shall we do with our Daughters?” she called on her listeners to prepare the next generation of women to take their rightful place in the affairs of the world. The last was her most popular lecture, revised annually and delivered more than eight hundred times.

The couple planned their lives carefully, with Daniel doing library research for Mary’s lectures and joining her at regular intervals when she was traveling on the circuit. In addition, they took several trips abroad together. Immensely popular as a public speaker, Mary became known as “the Queen of the American Platform.” She was the author of two substantial books: My Story of the War, published in 1887, an account of her work with the Sanitary Commission, and The Story of My Life, published in 1897. Of particular interest in the latter are accounts of her experiences as tutor on the Virginia plantation and as a young minister’s wife.

Both Mary and Daniel retained their commitment to Universalism throughout their lives, regarding its principles as central to their work. During their Melrose years, Daniel wrote in support of women’s rights while regularly supplying pulpits in the Boston area. He preached at Hingham for ten years. Meanwhile, in 1873, Mary was chosen as the first president of the Association for Advancement of Women. In 1875 she became president of the American Woman Suffrage Association and began her twenty-year presidency of the Massachusetts Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

Mary often spoke from Universalist pulpits and at denominational and interdenominational meetings. As a major speaker at the Murray Centennial celebration at Gloucester in 1870, she shared her expectation that “through the doctrines of Universalism” sin will be overcome. She held up her vision of “the great, grand time . . . [when] we shall have but one worship, that of the Universal Father, who embraces in His nature every form of love known to us . . . ; when we shall recognize the great tie of brotherhood the world over; when we shall be done with wars and battles; when we shall come together as one people, with the Lord God our Father and our Leader.”

Like many other Universalists, Mary was interested in spiritualism. Following Daniel’s death she became convinced that he had communicated with her through a medium. Thus their relationship continued for the remaining few years of her life.

Only one letter survives of long correspondence between Mary and Daniel Livermore. The manuscript letter is in the Firestone Library at Princeton University. Other correspondence and papers of Mary Livermore are in the Kate Field Collection at the Boston Public Library; the Mary Livermore Collection at the Melrose Public Library, Melrose, Massachusetts; the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts; the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Stowe-Day Foundation Library, Hartford, Connecticut; the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Massachusetts; and the Library of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts. Some of Mary Livermore’s lectures are collected in What Shall We Do with Our Our Daughters? Superfluous Women, and Other Lectures (1883). With Frances E. Willard, she edited A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (1893). In addition to books mentioned in the article above, she wrote Nineteen Pen Pictures (1863). For more on the work of the U. S. Sanitary Commission see Mary A. Livermore “Massachusetts Women in the Civil War,” in Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Massachusetts in the Army and Navy During the War of 1861-65, Volume II (1895).

Daniel Livermore wrote a number of Universalist theological and pastoral works, including Orthodoxy as it is; or, Its Mental Influence and Practical Inefficiency and Effects Illustrated by Philosophy and Facts (1845), with R. Tomlinson; Bible Doctrine of Hell: Or a Brief Examination of Four Original Words, Sheol, Hades, Gehenna, and Tartarus, Rendered Hell in the Scriptures (1861); Guide to Universalist Theology, Being a Succinct Statement and Brief Defence of the Doctrine of Universalism (1862); Proof-Texts of Endless Punishment Examined and Explained (1862; enlarged edition, 1864); and Comfort in Sorrow: A Token for the Bereaved (1866). Some of his many writings on women’s suffrage were The Arguments against Woman Suffrage by Mrs. Clara T. Leonard, Hon. George C. Crocker, Francis Parkman, Esq., and Mrs. Kate Gannett Wells, Carefully Examined and Completely Refuted (1884); Woman Suffrage Defended by Irrefutable Arguments (1885); and Business Capacity of Women (n.d).

Aside from Mary Livermore’s autobiographical works there is only one full-length biography: Wendy Venet, A Strong-Minded Woman (2005). Charles A. Howe has written a couple of articles on the Livermores: “Daniel and Mary Livermore: The Biography of a Marriage,” Proceedings of the UU Historical Society, (1982-83); and “Mary and Daniel Livermore: The Chicago Years,” Kairos (Spring, 1982). Other information on Mary Livermore can be found in George Hunston Williams, American Universalism (1971); and Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, vols 1 and 2 (1979, 1985). An early biography of Mary can be found in the Ladies’ Repository (1868). Obituaries for Daniel Livermore are in the Universalist Leader (July 15, 1899) and the Universalist Register (1900).

Article by Charles A. Howe

Posted February 26, 2001