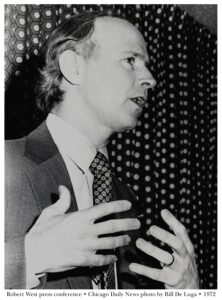

Robert Nelson West (January 28, 1929-September 27, 2017) was a Unitarian Universalist minister and the second president of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). During his presidency (1969-1977) he rescued the Association from bankruptcy, and then reshaped it’s internal structure. Through careful stewardship and increased outside funding he assured that it had a reliable economic base. In 1971 he authorized the denomination’s Beacon Press to publish The Pentagon Papers which detailed the American government’s role in the Vietnam War. After serving eight years as UUA President, West moved on to a forty-year career in corporate and legal consulting.

Robert Nelson West (January 28, 1929-September 27, 2017) was a Unitarian Universalist minister and the second president of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). During his presidency (1969-1977) he rescued the Association from bankruptcy, and then reshaped it’s internal structure. Through careful stewardship and increased outside funding he assured that it had a reliable economic base. In 1971 he authorized the denomination’s Beacon Press to publish The Pentagon Papers which detailed the American government’s role in the Vietnam War. After serving eight years as UUA President, West moved on to a forty-year career in corporate and legal consulting.

He was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, the eighth of ten children in the family of Mary Evelyn (Wells) and Samuel Washington West. His father worked for the United States Post Office. West was Raised in the Methodist faith and throughout his life he enjoyed “belting” out the hymns he had learned in childhood. Educated in Lynchburg’s segregated public schools, he graduated from its “white” High School in 1946.

West spent the next two years in the United States Navy as an aviation control tower operator. In 1948, after discharge, he enrolled at Lynchburg College using his GI Bill benefits. The college, founded in his birth city in 1903 as Virginia Christian College would be renamed the University of Lynchburg in 2018. The school had been coeducational from the start but was not integrated during his years there. He elected English as his major, and in 1950 the college awarded him the Bachelor of Arts degree.

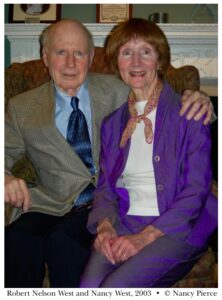

When West was a senior at Lynchburg College he met and fell in love with Nancy Kathryn Smith. She had just started her musical studies at the college and she planned to pursue a career as a professional pianist. They both loved the piano, particularly the blues and boogie-woogie, so they often teamed up to play at campus parties and on local radio stations.

After graduation, West took courses about the insurance business at the Law School of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., 1950-51. He then went to work selling insurance for W. R. Smith, the father of the girl he had fallen in love with at college. They were married on May 5, 1951 by the Rev. Richard H. Lee, a local Episcopalian minister. With marriage, the owner of the firm he worked for also became his father-in-law.

After Nancy Kathryn graduated in 1953, they lived in her hometown of Altavista, Virginia where the family business was located. By then West was its manager and Nancy Kathryn was a secretary. In the decades following college she was regularly engaged by hotels to play in their cocktail lounges. Throughout their marriage they would delight in playing four-handed piano. That marriage lasted sixty-five years and produced four children, three sons and a daughter. One of the eulogists at West’s memorial service said: “Their love shone through every time he talked about her.”

West undertook an examination of his religious beliefs during the early 1950s, hoping to find something more compatible than the Methodist church of his childhood. His wife had been raised in a liberal household, her parents, “a rarity—southern Unitarians,” attended the First Unitarian Church of Richmond, Virginia. The West’s soon became members; indeed, Nancy joined before he did.

Discovering liberal religion furthered West’s interest in the ministry. He often discussed it with their minister, Dilworth Lupton. Finally, with Nancy’s encouragement and backing, he decided to go back to school. The family moved to Berkeley, California in 1954 and he enrolled at the Starr King School for the Ministry. Three years later, in 1957, he had earned his M.Div., and had accepted an invitation from the congregation of the Tennessee Valley Unitarian Church, Knoxville, Tennessee to be their minister.

He was minister in Knoxville from 1957 until 1963. The three hundred members of the congregation and the minister proved to be a good match. West was also active in the life of the larger community, which at the time was still quite segregated. An example was his support in 1961 of the Knoxville College black student sit-in to desegregate the city’s “whites-only” lunch counters. At first West advised his congregation to take no part in the sit-ins for he believed that the stores had the right to serve just whom they wished. Other “liberals” took the same position, believing that “time” would solve the city’s racial problem. Soon, however, West and his congregation became actively engaged in helping to solve the crisis. Michael Proudfoot, who participated in the sit-ins, wrote that besides supporting the counter sit-ins, West also urged the students to cancel the credit cards that they used at the city’s other department stores, which also discriminated against blacks. After a month of protests the storeowners agreed to the students’ demand, and the civil action concluded peacefully and successfully.

In 1963 he became minister of the nine hundred-member First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York. He told his new congregation that he and his family anticipated that their time together would be “one of fruitfulness and meaning . . . . mutual growth and understanding.”

Once again he became a community leader, especially for civil rights. Soon after his arrival West took part in the August 1963 March on Washington, D. C. for Jobs and Freedom. There he heard Martin Luther King, Jr. deliver his prophetic “I have a Dream” speech. The following year, after a three day race riot in Rochester, New York, West, and members of his congregation, led a fund raising drive among the Rochester Area Council of Churches. The drive collected $100,000 to bring Saul Alinsky, the founder of modern community organizing, to Rochester to augment the African-American community’s pressure on Kodak, Xerox, and the local government to initiate job training programs, improve hiring practices, and secure affordable housing.

Once again he became a community leader, especially for civil rights. Soon after his arrival West took part in the August 1963 March on Washington, D. C. for Jobs and Freedom. There he heard Martin Luther King, Jr. deliver his prophetic “I have a Dream” speech. The following year, after a three day race riot in Rochester, New York, West, and members of his congregation, led a fund raising drive among the Rochester Area Council of Churches. The drive collected $100,000 to bring Saul Alinsky, the founder of modern community organizing, to Rochester to augment the African-American community’s pressure on Kodak, Xerox, and the local government to initiate job training programs, improve hiring practices, and secure affordable housing.

In 1965 West responded to Martin Luther King’s nationwide call for volunteers to join in a second Selma to Montgomery civil rights protest march in Alabama. The first march had ended in violence: The second would end in death for two of West’s Unitarian Universalist colleagues, the Rev. James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo.

Besides ministering to his two congregations, West actively worked to promote the larger goals of the denomination. His contributions ranged from being President of the Starr King Theological School Alumni Association and a member of the schools’ Board of Trustees, to various committee positions supporting the UUA’s work on such matters as dealing with curriculum and certification for professional Directors of Religious Education, and the formation of regional districts. He was also an advisor for Liberal Religious Youth conferences and a member of the Business Committee of the UUA’s General Assembly (GA). In addition to his UU activity, West supported the work of many other organizations; including the Mental Health Association, the New York State Civil Liberties Union, Family Service, and the Human Relations Council.

In 1969 the UUA was seeking a new president because its bylaws prevented Dana Greeley, UUA president at the time, from running for a third term. Many thought Paul Carnes, the minister in Buffalo, New York, would be a good choice for the position. Carnes was interested, but decided not to run at that time because of health problems with cancer. But Carnes did urge West to run, and he volunteered to be West’s campaign manager. There were already two officially announced candidates: Rev. Harry Scholefield, minister in San Francisco and Robert Hohler, a lay man and the executive director of the UU Laymen’s League. The chief issues addressed in the campaign, and they were to cause much bitterness, centered on the association’s financial condition, the turmoil around Black empowerment and self-determination, and disagreements about America’s Vietnam War.

West thought the matter over, and then in August 1968 he sent Carnes, who was traveling in Europe, a telegram, which said that he would not run. This led to further discussion. In the end West decided to seek the presidency with the caveat that if Schofield was seen to be the choice he would withdraw and support him out of respect for his “impressive” qualities of leadership. What happened, however, was that after West entered the race. Hohler and Schofield withdrew. This left West alone, but eventually six other men became candidates. As Conrad Wright later noted the total campaign cost of the contest amounted to $32,353.77.

When the votes were counted at the General Assembly (GA), West received 1,025 out of the nearly 2,000 votes cast. West felt the vote was an endorsement of the platform he had run on; that the UUA is “a family of congregations and is the continental expression of our free religious movement [whose] primary purpose is to serve local congregations” with “programs and services our members need and want.”

The election of a president was not the only contentious GA debate that year, for the matter of Black empowerment, as expressed by the Black Affairs Council (BAC) and Black and White Action (BAWA), resulted in many African-American Unitarian Universalists, and others, especially the Rev. Jack Mendelsohn, minister of Boston’s Arlington Street Church, getting up and walking out. After much debate, marked by hostility among people of basic goodwill, the GA funded BAC for that UUA financial year, but did not fund BAWA; it also increased financial support for theological schools, Chicano programs, religious education, the United Nations Office, and the Canadian Unitarian Council. The GA also instructed the new president and Board of Trustees to move to balanced the budget as quickly as possible.

Increased spending furthered the UUA’s financial crisis and threatened the existence of the association. In addition, West soon learned that the previous administration had exhausted the UUA’s unrestricted capital funds, and that just two weeks before GA, the UUA had borrowed another $50,000 from a bank already holding an open demand note for $400,000. After a few months of negotiations, West and the UUA treasurer were able to satisfy the bank’s concern by assuring them they “. . . would apply the full amount of every unrestricted bequest the Association received until the note was retired.”

As for the operating budget, it called for spending $2.6 million with an income of just $1.6 million. This meant that West, the UUA Moderator Joseph Fisher, and the UUA Trustees, would have to make dramatic cuts in order for the UUA to continue serving even the minimum needs of congregations. The Greeley administration had already started this process, but it was left to the new administration to really deal with the situation.

Staff and services were quickly cut to close the million dollar budget shortfall. The UUA staff was cut from 108 people to 55, departments such as those for Social Responsibility and Overseas and Interfaith Work were consolidated, the number of national district officers was reduced from 21 to 7, the flashy UUA Now monthly magazine with about 7,000 subscribers was replaced with a free newspaper, the UU World, which went to more than 110 thousand families, and support for Liberal Religious Youth, Student Religious Youth, and other affiliated organizations was trimmed. The most controversial cuts though, were those to the funding promised to the Black Affairs Council. That fight went on for several years, ending up in the courts. These unresolved funding controversies would fade away and then resurface in the coming decades.

In 1970, the Meadville Lombard Theological School in Chicago awarded West an honorary D. D. degree. Many Unitarian Universalists, congregations, ministers, and affiliated organizations were deeply unhappy with the actions the Meadville Lombard Trustees had taken, and reacted with anger and antagonism, especially toward West. It was so violent and vicious that it took decades before the denomination would understand that West and the board of trustees had acted in a manner, which allowed the UUA to again become a positive part of the movement.

In 2004 when West received the denomination’s highest honor, its Distinguished Service to Unitarian Universalist Award, the then president, William G. Sinkford, clearly remembering the personal pain the presidential years had caused West, said, “He always had the best interests of the Association in mind, and we handled the differences of opinion badly.” And he, on behalf of the denomination, then apologized to West “for the treatment he had received in the past.”

Throughout West’s two terms, UUA budgets were based on realistic expectations of annual income from all sources. Balance was reached by 1973 but two years later further staff cuts were necessary to insure that the organization remained financially sound. This was partly due to the costly publication by Beacon Press of the Pentagon Papers, but West was able to keep the UUA financially healthful in part because of generous funding gifts regularly made by the Veatch Program of the UU Church of Plandome, New York, and by the Jonathan Holdeen trusts.

Throughout West’s two terms, UUA budgets were based on realistic expectations of annual income from all sources. Balance was reached by 1973 but two years later further staff cuts were necessary to insure that the organization remained financially sound. This was partly due to the costly publication by Beacon Press of the Pentagon Papers, but West was able to keep the UUA financially healthful in part because of generous funding gifts regularly made by the Veatch Program of the UU Church of Plandome, New York, and by the Jonathan Holdeen trusts.

West held many meetings with the Plandome congregation and its Veatch Committee to convince them that the UUA had changed its spending habits and now operated on sound financial principles. “It would be difficult.” West wrote in his memoir, “to exaggerate the contribution of the Plandome church in enabling our Association to continue as an effective liberal religious continental denomination.” The Holdeen trusts were complicated charitable trusts that had been established by Jonathan Holdeen, an eccentric businessman and lawyer, and never a UU. The UUA received some income from some of these trusts but when West examined the matter he felt that the Association was not receiving its fair share from the trusts’ trustees. Therefore, even though the matter would not be resolved during his administration, he authorized legal action. The case was not finally concluded until 1977, and the decision granted the UUA proper “past and future” income from the trusts applicable to them. This has amounted to millions of dollars, which the UUA has used in several ways, largely as directed by Holdeen, “to benefit Asian Indians,” but also to support the work of the International Association for Religious Freedom, the International Council of Unitarian and Universalists, the Liberal Religious Charitable Society, the World Conference on Religion and Peace, and the Partner Church Council.

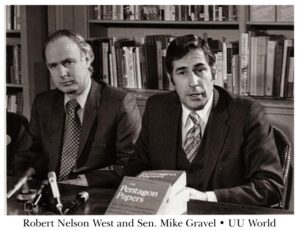

On July 26, 1971 Beacon Press was “approached” to publish a complete edition of the Pentagon Papers: the Defense Department History of the United States Decisionmaking on Viet Nam. This “secret” 1969 study of America military involvement had been commissioned by Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense. In time its contents were “leaked” by Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo to the New York Times, which published parts of the report. Soon others did the same, but no one had yet published the complete study. Indeed, thirty-five publishers had refused to do so. After considering the project, the editor of Beacon Press, Gobin Stair, asked West for permission for Beacon to publish in full “the Senator Gravel edition” of the text. Mike Gravel, a Democrat, was then one of Senators from Alaska in the U.S. Congress. He was also a Unitarian Universalist. The publishing cost was estimated to be $50,000. West approved it and on August 17, 1971, 20,000 copies of the four-volume set were printed.

The government’s response was immediate. The Defense Department released its “version” of the study, two of its agents visited Stair at his office, which was followed by a call from President Nixon. The visit and call were threatening events. The intimidation continued with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), under orders from a federal grand jury, going to the UUA’s bank and examining its financial records, including checks from all of its contributors. Senator Gravel then brought the matter to the Appeal’s Court, which declared that as a Senator he had immunity in this matter, but that the UUA did not.

At that point, the UUA filed a suit to halt the government’s investigation. Eventually the Supreme Court reviewed the matter. By a vote of five to four that court rejected the appeal made by the UUA. The government now moved to continue its investigation by subpoenaing Beacon Press Editor Gobin Stair as a witness in its case again Ellsberg and Russo, and ordered him to bring all of Beacon Press’ data about the matter to the Los Angeles court hearing. West was also prepared by the UUA lawyers to expect a subpoena, but then, due to various illegal White House actions against Ellsberg’s constitutional rights, the judge declared a mistrial. In February 1974 the government told the Boston federal court that it was not planning any immediate further action, and so the thirty-one month case was finally “dismissed without prejudice.” Publishing the Pentagon Papers was an expensive, but necessary undertaking, for as West had told the court, “At the core of the Unitarian and Universalist religion are freedom of conscience, individual freedom of belief, and the application of one’s religion in daily actions of public and private nature.”

As their term as President and Moderator was approaching its end, West and Fisher discussed the question of whether they should run for re-election. Their decision was they should for they felt that not to do so might precipitate a divisive election based on the old wounds of 1969-1971. Fortunately for the UUA they ran unopposed.

This enabled West to further improve the organization’s structure and programs. These accomplishments included opening meetings of the Board of Trustees to observers; keeping more accurate church membership records; establishing at the request of the UUA staff organization objective and fair “human service” standards; appointing in 1975 Doris Pullen as the first female member of the UUA executive staff (she was the director and editor-in-chief of the Department of Communications and Development); setting up a “sharing in Growth” experiment to promote both individual church growth and religious depth; appointing a Ministerial Education Commission charged with making recommendations concerning theological school funding and improving the education of religious professionals; guiding to publication the UUA’s course, About Your Sexuality; and establishing its first Office for Gay and Lesbian Concerns.

During his first two years as president, West made no overseas trips to international religious liberal meetings. But that changed in 1972 when he started to attend the Council meetings of the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF), and was during the next few years instrumental in helping to arrange through the Veatch committee financial funding for IARF staff and programming.

Robert West left the presidency of the UUA in 1977. For the next forty years he had very little contact with the movement he had served so conscientiously. He and Nancy, however, continued to live in Boston where he worked as a senior consultant for the Arthur D. Little Corporation until 1981, and then as the executive director for the Boston law firms of Parker, Coulter, Daley and White until his retirement in 1993.

Until 2000 he had made only two visits to the denomination’s headquarters, and those were to honor—on their retirement—two members of the staff who he had closely worked with during his presidency. And although he and Nancy had regular monthly lunches with Martha and David Pohl, and Gene and Helen Pickett, essentially an entire UU generation passed before he felt comfortable in renewing, in a limited way, his engagement with the general denomination. It was Warren Ross, when he was writing his history of the UUA in 2000, The Premise and the Promise, who asked West if he would consent to be interviewed about his presidential days, and fortunately West agreed to do so. Ross’s account of those years was carefully and honestly done, and that allowed for the West administration to be appreciated, probably for the first time, by many in the denomination.

In 2001 West took part in a gathering about Beacon Press and the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which was soon followed by his attending the next session of the GA, the first he had gone to since leaving UUA headquarters. There he shared his UU story, and found that the denomination had begun to recognized the accomplishments of those days. In 2002 he took part with Gobin Stair in an event at Arlington Street Church about the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

In 2001 West took part in a gathering about Beacon Press and the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which was soon followed by his attending the next session of the GA, the first he had gone to since leaving UUA headquarters. There he shared his UU story, and found that the denomination had begun to recognized the accomplishments of those days. In 2002 he took part with Gobin Stair in an event at Arlington Street Church about the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

This led to his receiving the UUA’s Distinguished Service Award in 2004, and to his formally researching and writing over three years his 2007 memoir, Crisis and Change, My Years as President of the Unitarian Universalist Association, 1969-1977. His final national honor came from Lynchburg College where he had earned his undergraduate degree. They awarded him an honorary D.D. in 2014 for his “outstanding contribution to the Unitarian Universalist Association.”

Nancy died on September 18, 2016, which left him, he said, “so empty.” He died a year later, on September 27, 2017. The family held a Memorial Service for him at First Church in Boston on Saturday, October 11, 2017. David Pohl, one of the eulogists, said, “Bob was, as we know, a very private person and kept the door to his president’s office closed most of the time. But away from his work, his kindness and mirth would enliven countless social occasions.” Another, John Hurley, said, “Bob West was a good and decent man who served the Unitarian Universalist movement and the causes of civil liberties and equality well.”

West’s papers as President of the Unitarian Universalist Association, his minister file, and his personal papers are in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Biographical data can be found in his memoir, Crisis and Change, My Years as President of the Unitarian Universalist Association, 1969-1977 (2007); Warren R. Ross, The Premise and the Promise The Story of the Unitarian Universalist Association (2001); and in Mark W. Harris, Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism (2004). Also useful are the remarks given by John Hurley, Carl Scovel, and David C. Pohl at the November 11, 2017 Memorial Service at First Church in Boston, Massachusetts. Gene Picket and David C. Pohl also provided useful remembrances of Nancy West at an October 13, 2016 First Church memorial gathering.

For information about his ministry in Knoxville see Merrill Proudfoot, Diary of a Sit-in, (1962) and Cynthia Griggs Fleming, “White Lunch Counters and Black Consciousness: the Story of the Knoxville Sit-ins,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly (1990). For discussions of West’s presidency and the crucial denominational issues of the time see: Warren R. Ross, The Premise and the Promise: The Story of the Unitarian Universalist Association, (2001); Raymond C. Hopkins, “Recollections, 1944-1974: The Creation of the Unitarian Universalist Association and the Administrations of Dana Greeley and Robert West,” Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2006-2007); Conrad Wright, Congregational Polity A Historical Survey of Unitarian and Universalist Practice (1997); “The Empowerment Saga” in Mark Morrison-Reed, ed., Darkening the Doorways: Black Trailblazers and Missed Opportunities in Unitarian Universalism (2011); Victor H. Carpenter’s 1983 Minns Lecture published as, Long Challenge: The Empowerment Controversy (1967-1977) (2003); Victor H. Carpenter, Unitarian Universalism and the Quest for Racial Justice (1993); Mark Morrison-Reed, The Selma Awakening: How the Civil Rights Movement Tested and Changed Unitarian Universalism (2014); Mark Morrison-Reed, Ménage a Trois: the UUA, GAUFCC and the IARF and the Birth of the ICUU (2017), available on-line as a PDF download at www.ICUU.net; and Mark Morrison-Reed, Revisiting the Empowerment Controversy: Black Power and Unitarian Universalism (2018).

Obituaries are in the UU World (October 30, 2017) and the Boston Globe (November 7, 2017). West is listed in Who’s Who in the East (some dates are wrong), Who’s Who in Religion, and Warren Allen Smith, Who’s Who in Hell: A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalist, Rationalists and Non-Theists (2000).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted July 26, 2018