Von Ogden Vogt (February 25, 1879-August 2, 1964), or V. Ogden Vogt as he preferred, was minister at the First Unitarian Church of Chicago for two decades, a lecturer on Religion and Fine Art at the Chicago Theological Seminary, and the author of books and articles on church art, architecture, liturgy, and worship.

He was born in Altamont, Illinois to Mary “Mollie” Elizabeth (Stair) and Ezra W. Vogt. His father had graduated from Heidelberg University in Baden-Württemberg, Germany but worked as a shoe merchant in Illinois. The family moved frequently due to his father’s poor health. Vogt was educated in the public schools of Redfield, South Dakota until 1889, the Salt Lake Academy in Salt Lake City until 1891, and then Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois. He was always an excellent student. When he was sixteen, he had to leave high school for a year to help support the family, but was able to return, become class president in his senior year, and graduate in 1897.

He was born in Altamont, Illinois to Mary “Mollie” Elizabeth (Stair) and Ezra W. Vogt. His father had graduated from Heidelberg University in Baden-Württemberg, Germany but worked as a shoe merchant in Illinois. The family moved frequently due to his father’s poor health. Vogt was educated in the public schools of Redfield, South Dakota until 1889, the Salt Lake Academy in Salt Lake City until 1891, and then Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois. He was always an excellent student. When he was sixteen, he had to leave high school for a year to help support the family, but was able to return, become class president in his senior year, and graduate in 1897.

As a child, his parents had him baptized in the Reformed Church and raised him in that faith. Later he declared, “much of my feeling in things ecclesiastical” was due to this heritage. Growing up he also attended the Congregational Church in Redfield, South Dakota and Woodlawn Presbyterian Church in Chicago, which he joined when he was fourteen.

His undergraduate college education was at Beloit College, Wisconsin where he earned an A B degree in 1901. While there he worked in the library, sang in the college choir and glee club, and was chair of the college’s prayer meeting committee. After graduation he remained at Beloit and worked as secretary to the college’s president, 1901-03. His chief duty was representing the college at regional church and school meetings.

Then in March 1903 he was offered and accepted the position of General Secretary of the United Society of Christian Endeavor at their headquarters in Boston, Massachusetts. Its mission was to provide programs, events, and publications appropriate to the needs of evangelistic young people. The position required extensive travel and public speaking. Vogt left Christian Endeavor in 1905 when he was appointed secretary in the Young People’s Missionary Department of the Presbyterian Church in New York City. This job introduced him to writing and publishing books; among these were Ba-he and the Shaman: The Story of a Navajo Rite between Sunset and Dawn (1908) and Desert, Mountain and Island: two studies on the Indians of Arizona, two studies of New Mexican Life, two studies of Porto Rico (1908). His work with religious organizations led Vogt to decide to train for the ministry. He entered Yale University where he earned a Master of Arts degree in 1909, and then enrolled at Harvard Divinity School. He stayed at Harvard just one term before transferring back to Yale Divinity School from which he graduated with the B D, magna cum laude, in 1911. In addition he won the Mersick Prize in preaching and gave a lecture on “Art and religion,” a harbinger of what would become the central theme of his ministry.

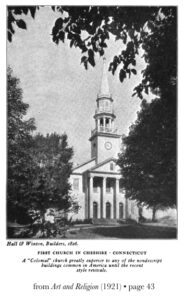

In July 1911 he accepted a call to the First Congregational Church of Cheshire, Connecticut. It was a small rural congregation with about one hundred members. On February 1, 1912 his flock ordained him to the Congregational ministry. They also built a neo-Federal parsonage facing the town green that year and named it in his honor.

In July 1911 he accepted a call to the First Congregational Church of Cheshire, Connecticut. It was a small rural congregation with about one hundred members. On February 1, 1912 his flock ordained him to the Congregational ministry. They also built a neo-Federal parsonage facing the town green that year and named it in his honor.

It was here that he met his future wife Ellen “Nellie” Baldwin Walter. They married in 1913 and had two sons, Philip and Walter. She was a physical education teacher, and when they lived in Chicago, Illinois she directed one of it’s YWCAs.

When Vogt was thirty-seven, in 1916, the larger and wealthier Wellington Avenue Congregational Church in Chicago called him as their minister. His eight years here were successful allowing him to write his influential book Art and Religion, which Yale University Press published in 1921. Well received, he revised and republished it in 1948 and again in 1960. Its theme defined his contribution to American Protestantism.

His basic thesis was that “beauty is desirable and good” and “that the religion of Protestantism stands profoundly in need of realizing” this truth. This is so because both art and religion need each other: art “to universalize its concept, to supply moral content” and religion “to be impressive, to get a hearing, to be enjoyable, to assist reverence, to symbolize old truths, to heighten the imagination, to fire resolves.” Religion achieves this through symbols, sacraments, rituals, music, aesthetics, and architecture. That is the substance of Christian worship and comes to fruition in its Order of Worship. “Vision, Humility, Vitality, Illumination, Enlistment—these constitute the experience of worship, and these may all be kindled in the experience of beauty.”

After discussing the various elements of worship services Vogt concluded that the future church, whose style for him would be of Gothic derivation, “will value and enjoy beauty” and teach concepts that promote and express “ideas in form of beauty” through music, art and liturgy. In other words, “it will set forth the oneness of life not only theologically and ethically but also aesthetically.”

A year later he wrote Syllabus of Proposals: A Free Cathedral or Collegiate Church for Chicago (1922), a short description of what a church would be like if it followed the ideas he had set down in Art and Religion.

The Syllabus appeared first in his church newsletter, next in The Christian Century as “A Free Cathedral” and finally in pamphlet form. It called for “a cathedral system” to serve “religion in the big American city.” Such an institution would not be “the idea in its medieval aspects, but its comprehending, catholic, community aspects.” Such a church would require several denominations to federate and share a “common system of public worship, as well as a common school for the religious education of the young.” There would further be a “wider union of the cathedral organization” that would “be administered by a chapter of cathedral clergy.” Obviously the city he had in mind to start the process would be Chicago and one of the first churches to be in the federation would be his.

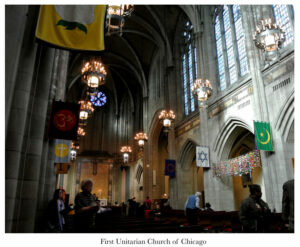

The Wellington Avenue Church had just been built, 1910, so it would be hard to create his new cathedral there. Fortunately, however, the First Unitarian Church of Chicago, located in Hyde Park, was soon seeking a new minister and had hopes of enlarging its present small structure. Through the intervention of a wealthy member, Morton Denison Hull, Vogt was invited to become their minister in 1925. Further, Hull was so inspired by Vogt’s liberal Christian beliefs and artistic ideas that he provided the parish with the funds to build its stone English Gothic (or Perpendicular Gothic) edifice. Vogt applied for dual fellowship with the Unitarians and was easily granted it by the American Unitarian Association (AUA). So started his nearly twenty-year ministry at First Unitarian Church and as its historian declared, “the modern era of our Society began.”

The Wellington Avenue Church had just been built, 1910, so it would be hard to create his new cathedral there. Fortunately, however, the First Unitarian Church of Chicago, located in Hyde Park, was soon seeking a new minister and had hopes of enlarging its present small structure. Through the intervention of a wealthy member, Morton Denison Hull, Vogt was invited to become their minister in 1925. Further, Hull was so inspired by Vogt’s liberal Christian beliefs and artistic ideas that he provided the parish with the funds to build its stone English Gothic (or Perpendicular Gothic) edifice. Vogt applied for dual fellowship with the Unitarians and was easily granted it by the American Unitarian Association (AUA). So started his nearly twenty-year ministry at First Unitarian Church and as its historian declared, “the modern era of our Society began.”

Hull’s son, Denison B. Hull, a graduate of Harvard and an architect, who was also to draw the plan for the nearby Meadville Theological School, was chosen to design the Church. He and Vogt worked closely together on the project, which was completed in 1929. The older church was incorporated into the new structure as a transept called Hull Chapel. The church itself combined “Gothic vocabularies in form and style” with a “liberal Protestant iconography of Unity.” It featured a stone-vaulted nave, chancel, rose window, crypt, and symbols that represented various Christian traditions, shields from older and current world religions, and roundels that signified humanity’s everyday activities and artistic accomplishments. The completed edifice has been called majestic and magnificent and as John Haywood, Vogt’s student, Unitarian philosopher, and friend wrote, “his greatest work.”

While the plans for the church were taking shape, Vogt started teaching as a lecturer on Christian art, architecture, and liturgies at the nearby Chicago Divinity School, a post he held from 1925 until his retirement in 1944. He also taught that subject at Beloit College,1927-28, and briefly at Meadville Theological School and the University of Chicago.

During this busy period he wrote his second book, Modern Worship (1927). Based on a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Massachusetts earlier that year. In it he spelled out his theory of worship. Each service he maintained should start with “praise” for life and all that supports it. Next should be an act of contribution for the “divine benefit” which is ours, followed by the ways that our life with others can help and sustain our religious community. Then, once again, the worshiper should be filled with and express “praise.” He came to call worship “a celebration of life,” a definition which touched a responsive chord for many, it was the chosen as the title for the first hymnbook put out in 1964 by the newly formed Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).

While his ideas and practices received limited acceptance among Unitarians and Universalists, they were favorably received by many other American Protestant denominations. James F. White, of the Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, writing in the 1970s about the “Gothic Revival” in architecture and worship in Protestant America termed the period 1920-1945 as “when worship came to be understood as largely an aesthetic experience by many ministers and lay people.” For them, Vogt’s Art and Religion was “probably the most representative book” on worship to read and study. White concluded that for Vogt “his earlier writings exhibit the Gothic Revival becoming domesticated among liberal Protestants; his later writings reflect the subsequent rejection of Gothic and the search for a contemporary style with few historic roots.” This broad period of experimentation in worship, then, enabled his ideas to have a wide relevance.

Beloit College gave him the honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree, 1929 and four years later the Meadville Lombard Theological School awarded him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

In addition to parish duties at First Unitarian Church of Chicago, Vogt was active in the Unitarian and Congregational denominations at the national level. He served as President of the Religious Art Guild, Unitarian, 1935-42, and was on the Unitarian and Universalist Commission that produced Hymns of the Spirit (1937), the hymnbook used by both denominations until they consolidated into the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) in 1961. In 1937 he was chosen to deliver the annual Berry Street Essay at the May Meeting of the AUA Ministerial Conference. Entitled “The Church and the Academy” it was published in the summer issue of Christendom and then as a pamphlet by the Unitarian Student Commission. In 1940 the Unitarian Young People’s Religious Union published his Manual of Worship for Young People’s Groups. From 1942 through 1946, he was a Master Craftsman in Liturgics for the Congregational Christian Church Arts Guild and in 1948 was given a citation from the Unitarian Religious Art Guild for his “distinguished” service.

In addition to parish duties at First Unitarian Church of Chicago, Vogt was active in the Unitarian and Congregational denominations at the national level. He served as President of the Religious Art Guild, Unitarian, 1935-42, and was on the Unitarian and Universalist Commission that produced Hymns of the Spirit (1937), the hymnbook used by both denominations until they consolidated into the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) in 1961. In 1937 he was chosen to deliver the annual Berry Street Essay at the May Meeting of the AUA Ministerial Conference. Entitled “The Church and the Academy” it was published in the summer issue of Christendom and then as a pamphlet by the Unitarian Student Commission. In 1940 the Unitarian Young People’s Religious Union published his Manual of Worship for Young People’s Groups. From 1942 through 1946, he was a Master Craftsman in Liturgics for the Congregational Christian Church Arts Guild and in 1948 was given a citation from the Unitarian Religious Art Guild for his “distinguished” service.

When Vogt, who had been in poor health for some time, retired in 1944, the congregation made him Minister Emeritus. He and Nellie moved to Vero Beach, Florida but regularly visited Chicago, often preaching there. He also spoke at the newly formed First Unitarian Society of Palm Beach County about once a month, 1956-58, and he was active in the Vero Beach community supporting and promoting the work of the town’s public library.

In 1951 on the fiftieth anniversary of his graduation from Beloit, its Alumni Association gave him a Distinguished Service Citation, which honored his “inspiring” ministry, his excellent teaching at Beloit and the Chicago Theological Seminary, and his books and articles “on ecclesiastical form in service and structures.”

Although retired he continued writing books and articles and reviewing volumes dealing with worship and the religious arts. In 1948 he gave the Minns Lecture on “Religion and American Culture.” Macmillan published his Cult and Culture, A Study of Religion and American Culture in 1951. “His thesis,” wrote one reviewer, was “that the only possible unifying force” for a divided America is a religion that is “broadly liberal” and that “expresses itself on the one hand in rich and artistic liturgy and on the other in social action aimed at the solution of our national problems.” Beacon Press issued his final two books: The Primacy of Worship (1958) where his premise was “derived from the mergence of the Platonic ideas of truth, goodness and beauty, the most religious value in our classic heritage” and a final revision of his popular Art and Religion (1960).

In addition to these activities, Vogt kept abreast of denominational events and was especially interested in the work of Kenneth L. Patton at the Charles Street Meeting House in Boston. He said Patton’s Readings for the Celebration of Life was “a collection of the most original and stimulating new materials for common worship now available. Here is gusto and reverence. Here is rich imagery, pungent phrase and challenging thrust.”

Vogt died at Vero Beach in August 2, 1964, a memorial service was held in Chicago that September, and his ashes were placed in the crypt of his beloved First Unitarian Church of Chicago. A plaque reads in part: His wisdom and artistry inspired the building of this house and fashioned its order of worship. His memory endures with these stones and lives anew in the voice of praise.

Vogt’s papers are at the First Unitarian Church in Chicago, Illinois. His Unitarian Universalist Association minister files are in the Andover-Harvard Theological Library at Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In addition to the books and articles mentioned above, his Minns lectures were published as Cult and culture, a study of religion and American culture (1951).

Biographical information can be found in Edward D. Eaton, “Von Ogden Vogt,” The Home Missionary (1903); General Catalogue of the Divinity School of Harvard University (1915); and John F. Hayward, “Von Ogden Vogt: Exemplar of Religion and Art,” Notable American Unitarians, 1936-1991 (2007) ed. Herbert F. Vetter.

Discussions of Vogt’s work include, James F. White, “Worship and Culture: Mirror or Beacon?” Theological Studies 34 (1973); James F. White, “Theology and Architecture in America: A Study of Three Leaders,” A Miscellany of American Christianity Essays in Honor of H. Shelton Smith (1963) Stuart C. Henry, ed.; Andrea Greenwood and Mark W. Harris, An Introduction to The Unitarian and Universalist Traditions (2011); Lester Mondale, “Von Ogden Vogt’s Art and Religion, UU Prairie Group Papers (1951); Frederick Swanson, The Experience of Worship: Von Ogden Vogt’s First Unitarian Church of Chicago (1979); and the Congregation of Abraxas, Worship Reader: Essays in Worship Theory from Von Ogden Vogt to the UUA Commission on Common Worship (1980). Vogt is also mentioned in congregational histories including Herman A. Newman, A History of the First Unitarian Society of Chicago: 1830-1933 (1933); Donald A. Thompson, The First Unitarian Society of Chicago: Its’ Relation to a Changing Community (1933); Esther Hornor, History of the First Unitarian Society of Chicago, 1836-1936 (1936); and Wallace P. Rusterholtz, The First Unitarian Society of Chicago: A Brief History (1979).

Vogt is listed in Who Was Who In America and American National Biography. Obituaries can be found in the Unitarian Universalist Register-Leader (1964), the United Church of Christ Year Book (1965); the Chicago Daily News, and the Vero Beach Press Journal. “The Contribution of Von Ogden Vogt” is on the Unitarian Universalist Association website while harvardsquarelibrary.org hosts the Vogt tribute by John F. Hayward, “Exemplar of Religion and Art.”

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted November 17, 2012