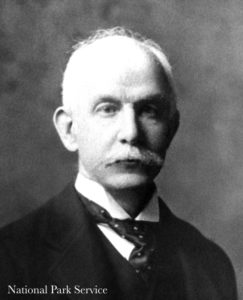

Peter Charadon Brooks Adams (June 24, 1848-February 14,1927) was a lawyer, historian, and writer, who served as an informal adviser to President Theodore Roosevelt. Although reared Unitarian, he was agnostic for many years. Late in life he returned to the Unitarian fold at the family church in Quincy, Massachusetts. Named for his grandfather Peter Charadon Brooks, he was called Brooks at his grandfather’s suggestion.

He was the youngest son of Abigail Brooks Adams and Charles Francis Adams, Sr. His mother was the youngest daughter of wealthy Unitarian Peter Charadon Brooks and Anna Gorham Brooks. President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848) was his grandfather and President John Adams (1735-1826) a great grandfather. His father, a diplomat, legislator, and writer was nominated for Vice President on the Free Soil ticket the year Brooks was born.

Brooks Adams was baptized by Nathaniel Frothingham, the Unitarian minister at First Church of Boston, Massachusetts. His mother and father, conscientious parents, took him to the new Sunday school at First Church where his father sometimes taught. Later his father was the Sunday school superintendent at their summer church in Quincy, Massachusetts. His parents worried about Brooks during his childhood; he seemed too active, was often inattentive, and sometimes made scenes in public. He collected stamps with a single-minded zeal that often interrupted family life, and he had reading and spelling problems that made his mother despair. In spite of these difficulties, his parents took young Brooks to places like the Smithsonian. He attended Columbia College in New York City, as did his sister Mary.

When his father went to England to represent the United States during the Civil War, Brooks went along, attending Wellesley House, a British public school. Although Brooks won prizes at Wellesley House in most subjects and acquired an English accent, he wasn’t ready for Harvard which required Greek and Latin. Returning home in 1865, he was tutored by Professor Ephraim Whitman Gurney. By the fall of 1866, he passed the Harvard entrance examination and enrolled. The curriculum had changed little in the ten years since his brother Henry Adams had attended. Brooks did not enjoy his studies, except for Ephraim Gurney’s course on Rome, nor did he apply himself. In time though, he matured overcoming most of his childhood problems. His brothers John and Charles disliked him while Henry treated him well. Brooks did nothing to improve his relationship with Charles when he charged a wine bill to his older brother. At Harvard, Brooks went out for rowing, and was the first Adams to get an invitation to join the prestigious Porcellian club. Following a trip west after graduation, Brooks decided to study law at Harvard Law School. He roomed with his brother Henry in Wadsworth House.

His father, Charles Francis Adams, Sr. returned to the diplomatic service in 1871 to negotiate Civil War damage claims against Great Britain over the building of the Confederate warship Alabama. President Grant opposed the appointment, but Secretary of State Hamilton Fish wanted Adams. When his father went to Geneva, Switzerland to take his place on the arbitration commission, Brooks, interrupting law school, went with him. His mother Abigail could not go. In 1870, his sister Louisa Catherine Adams, also in Europe, died in an Italian carriage accident. His father returned home when his mother became ill, but Brooks remained in Paris, not coming back to the United States until 1872. Once home, he studied law on his own, passed the bar, and opened a practice. In his free time he pursued his interest in reform including corresponding with journalist and poet William Cullen Bryant and other movement leaders. He wrote articles for the North American Review – which his brother Henry Adams edited – and The Atlantic Monthly. He ran for the General Court in 1877 but lost by two votes. In 1880 he had a breakdown that may have been caused by overwork. After recuperating in Florida he visited Henry who was living in Washington, D.C. In better health, Brooks returned to Quincy to care for his aging parents.

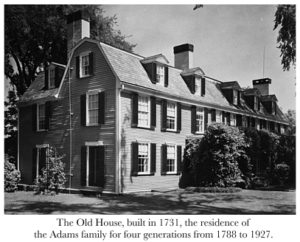

After his recovery he gave up law and turned to history. His ambition was to write a philosophy of history. His Emancipation of Massachusetts (1886), written during this period, told the story of the commonwealth, as a struggle against clerical domination. He told Henry Cabot Lodge; “It is not really a history of Massachusetts but a metaphysical and philosophical inquiry as to the actions of the human mind in the progress of civilization…” He strongly criticized the Cambridge Platform believing it furthered the aims of the Standing Order and limited religious liberty. This critique of the clergy and ancestor-venerating histories created much controversy. Influential, it would eventually change the historical interpretation of that period. His father died during the writing, but Brooks continued to live at the Old House and care for his mother. Following publication, William James and Thomas Wentworth Higginson corresponded with him about the book.

After their father’s death, his brother Henry alternated between staying in the Old House in Quincy with Brooks and living in Washington, D.C. with a niece for company. In 1888, as Henry Adams was finishing the ninth and final volume of his History of the United States, Henry decided to leave the Old House in Quincy because Brooks was growing too quarrelsome. Brooks said frankly; “I am a crank; few human beings can endure to have me near them…” After their mother’s 1889 death, Brooks decided it was time to get married. Henry Cabot Lodge’s wife suggested her sister Evelyn Davis. During their first carriage ride, Adams proposed, calling himself “eccentric almost to the point of madness” and warning her that she would marry him “at her own risk.” Nevertheless, the Admiral’s daughter accepted the challenge. Brooks and Evelyn were married at the Nahant Union Church with Episcopal Bishop Frederick Dan Huntington and Reverend W.A. Munsell presiding.

After their father’s death, his brother Henry alternated between staying in the Old House in Quincy with Brooks and living in Washington, D.C. with a niece for company. In 1888, as Henry Adams was finishing the ninth and final volume of his History of the United States, Henry decided to leave the Old House in Quincy because Brooks was growing too quarrelsome. Brooks said frankly; “I am a crank; few human beings can endure to have me near them…” After their mother’s 1889 death, Brooks decided it was time to get married. Henry Cabot Lodge’s wife suggested her sister Evelyn Davis. During their first carriage ride, Adams proposed, calling himself “eccentric almost to the point of madness” and warning her that she would marry him “at her own risk.” Nevertheless, the Admiral’s daughter accepted the challenge. Brooks and Evelyn were married at the Nahant Union Church with Episcopal Bishop Frederick Dan Huntington and Reverend W.A. Munsell presiding.

In 1893 the Adams brothers met in Quincy to deal with the financial panic that threatened the family trust. Brooks now became manager. In the hot August of that year, at the Old House in Quincy, Brooks discussed his manuscript for The Law of Civilization and Decay (1896) with Henry. Its arguments foreshadowed those of Spengler and Toynbee and influenced Henry’s thinking. In a later edition, it predicted that inexpensive labor from the Orient would some day compete with American labor. The United States, according to Brooks, was in a Darwinian struggle for survival. The book attracted the attention of then New York police commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt, who would remember Brooks ideas when he became President.

During the 1890’s, Brooks echoed the Populist anti-Semitic rhetoric prevalent at the time. An Anti-Dreyfusard, he engaged his brother Henry in protracted discussions. Brooks hated hereditary bankers including Armenians and Indian Marwari. However, he did not believe in racial purity, since he thought civilized societies should intermarry with aborigines.

In America’s Economic Supremacy (1900), Brooks predicted that in fifty years the United States and Russia would be the major powers. In the book, he also forecast the Russo-Japanese War and the Russian Revolution. Brooks had faith in trusts and empire. While Brooks’ brother Henry disagreed with the arguments and conclusions in America’s Economic Supremacy, he did agree that the reviews were too harsh. Unlike Brooks, brother Henry opposed imperialism, leaned toward socialism, and was against the Boer War.

Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt also disagreed with much of what Brooks had written. He once accused Brooks of being “touched in the head.” Nevertheless, Brooks became Roosevelt’s unofficial “Square Deal” adviser. Brooks, whose brother Charles Francis Adams, Jr. had been president of the Union Pacific Rail Road, was deeply involved with the Roosevelt administration’s interpretation of railroad law. Roosevelt met regularly with Brooks, who helped him shape the government’s Panama Canal and Manchurian policy, and to define the U.S. role in the Russo-Japanese peace agreement. Brooks abrasive personality relegated him to the role of an éminence grise, a behind the scenes political adviser. Theodore Roosevelt wanted to appoint him to a more visible position, but reluctantly concluded that he was “an unusable man.” Brooks believed “Teddy” was the best alternative for the country, while brother Henry – an anti-Imperialist and anti-militarist —thought “Teddy almost insane at times.

Brooks taught at Boston University, 1904-1911 as a lecturer of Constitutional Law. He explored the legal underpinnings of his economic theories on trusts and railroads. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was a close friend and intellectual influence whom Brooks was happy to see elevated to the Supreme Court.

Brooks voted Progressive in 1912, for his friend “Teddy” Roosevelt, even though it led to woman’s suffrage, which he opposed, the income tax, and inheritance taxes. Brooks had novel views about government; for example, he thought workers were entitled to stock or land, but that corporate boards should determine wages. His administrative ideas resembled those later held by Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR). A number of his shorter articles eventually were collected to form the 1913 book, Theory of Social Revolutions. He claimed that labor and capital were both monopolies. Like FDR, he was conservative, in the sense that he hoped reform could preserve the financial system. Another theme of the book was legal equality. He also forecast FDR’s Supreme Court battle. Brooks’ desire to write a platform for the defeated Theodore Roosevelt was, unfortunately, blemished by his gratuitous anti-Catholicism and authoritarian tendencies. Reviewing his brother’s book, Henry did his best to emphasize its strengths.

When the Great War broke out, Brooks was in Europe at Bad Kissingen, Bavaria, taking the water cure. He thought the war could go on for thirty years. Naturally, the Quincy parish turned to an Adams for leadership in crisis. However, Brooks was unchurched. When he returned to Quincy in the fall, his minister at First Parish asked him to join the church and declare his faith before the congregation. He did so with great hesitation, having been agnostic for so long. Standing at his inherited pew, he made ethics his religious standard. Like Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood, he endorsed America’s early preparation for war.

In 1917, Brooks and his nephew Charles were delegates to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. Curiously, the patrician Brooks argued for state socialism similar to Germany’s. He usually stood alone in his views, the other delegates often misunderstood him. Commenting on the convention, Henry wrote, “My solemn brother Brooks” is sitting with some five hundred other men in the State House trying to frame a new fabric for the Society of the next Century which shall satisfy some one [sic] although thus far he had got only to the point of dissatisfying every one [sic] more than ever.”

In his sixties, Brooks often claimed he was dying. A life-long curmudgeon, friends and relatives tended to ignore him. He lived for another decade, and continued to go his own way. After World War I, he opposed Wilson’s peace negotiations, he was discontented with most politicians; and he especially disliked Lloyd George, the Liberal Prime Minister (1916-22) of the United Kingdom. Morbidly thinking himself the last Adams, Brooks restored the Old House in Quincy and prepared it as a museum. In the 1920s, he retreated to Catholic monasteries, but he never converted. He grew ever more temperamental as his health failed. His wife was admitted to a sanitarium where she died in 1927. His death followed shortly thereafter. The Reverend Fred Alban, conducted the funeral at First Parish, Quincy – his great grandfather’s church – where Brooks had spoken at the 275th Anniversary celebration. Flags in Quincy flew at half-mast.

Brooks Adams’ grave is in Mt. Wollaston Cemetery, in Quincy, Massachusetts, near where he swam as a boy. Brooks was not as fierce as he sounded, and in the end provided generously for his caretakers and animals.

Sources

The principal archival repository for the Adams family is the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. The papers of Brooks Adams are also available in the microfilm edition of the Henry Adams letters. Additional material can be found in the Harvard University Archives, Boston University Archives, Library of Congress, New York Public Library, and at the Old House, Quincy, Massachusetts.

The best biographies of Brooks Adams are in journal form; Wilhelmina S. Harris, “The Brooks Adams I Knew” Yale Review, (1969) and Marc Friedlander, “Brooks Adams en Famille,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, (1968). Older biographies in book form that are useful include; Anderson Thornton, Brooks Adams: Constructive Conservative (1951); Arthur F. Beringause, Brooks Adams: A Biography (1955); and Timothy P. Donovan, Henry and Brooks Adams: The Education of Two American Historians (1961). For Brooks relationship with other family members see Francis Russell, Adams, an American Dynasty (1976).

Article by Wesley Hromatko

Posted August 18, 2012