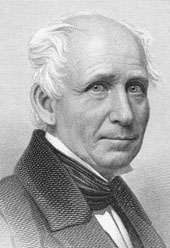

Hosea Ballou 2d (October 18, 1796-May 27, 1861), Universalist minister, scholar, educator, and journalist, was the grandnephew of the theologian and denominational leader Hosea Ballou. Ballou 2d played a crucial role defending the elder Ballou in the Restorationist controversy. He made the first substantial contribution to Universalist history, the monumental The Ancient History of Universalism, and worked to elevate the standard of Biblical criticism among Universalists. A mentor to many aspiring ministers, he was an early proponent of more formal theological education. He was a founder, and the first president, of Tufts College.

Hosea 2d was born in Guilford, Vermont, the son of a farming couple, Martha Starr and Asahel Ballou. Asahel was the son of Benjamin Ballou, Hosea Ballou’s oldest brother. Born three months before his uncle Hosea, Asahel was Hosea’s childhood companion and a friend throughout life. Both Martha and Asahel had originally been Baptists. They converted to Universalism in the early 1790s, before Hosea 2d was born.

Young Hosea’s early education at the public district school was supplemented with Latin lessons from local Congregationalist minister Thomas H. Wood. After the age of 14, he was largely self-educated. He was especially attracted to languages, eventually learning Latin, Greek, French, German, and some Hebrew. He spent three years teaching in public schools in Vermont. In 1812 his family briefly considered sending him to college, but decided not to do so, worried that he might be recruited there by the Congregationalists.

In 1813 Ballou 2d became an assistant to his great-uncle Hosea Ballou, who at that time was supplementing his ministerial income by operating a private school in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. For the next two years Ballou 2d taught at the school and was at the same time the elder Ballou’s first ministerial student. He adopted the theology his great-uncle held at that time, retaining belief in probationary punishment in the afterlife after his mentor had ceased to believe in it. Like other Ballou students, Ballou 2d was encouraged to write sermons and to begin preaching at an early date. By the end of 1816 he had delivered nearly fifty sermons in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts. In 1816 he was welcomed into fellowship by the New England General Convention.

Ballou 2d’s first settlement was at the Universalist church in Stafford, Connecticut, 1817-21. Based in Stafford, he traveled in a circuit embracing northeast Connecticut and adjoining areas of southern Massachusetts. In 1820 he married Clarissa Hatch, whom he had known from childhood.

On the advice of his great-uncle, Ballou 2d accepted a call from the new Universalist church in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Hosea Ballou and Paul Dean, Universalist ministers in Boston, had stirred up interest in Universalism in this Boston suburb by regularly lecturing there in 1820. Ballou 2d served the Roxbury society, 1821-38. At the same time he continued his language studies and, from 1826, ran a private school for boys. He served the church in Medford, Massachusetts, 1838-54.

Ballou 2d first wrote for the Universalist Magazine in 1819, the first year of its publication. He made more frequent contributions after his move to Roxbury, often using the pseudonym “Marcus.” From 1822-26 he was co-editor with Hosea Ballou and Ballou’s fiery young disciple, Thomas Whittemore.

During the 1820s and 30s Universalists were engaged in a bitter controversy between the “ultra” or “death and glory” Universalists, led by the elder Hosea Ballou, and the “Restorationists,” who believed in limited future punishment. Although Ballou 2d agreed theologically with the Restorationists, he condemned them—notably, Paul Dean, Edward Turner, and Jacob Wood—for the harshness of their attacks on his great-uncle. After the Restorationists in late 1822 had published two articles in the Christian Repository, “An Appeal to the Public” and a declaration “To the World,” Ballou 2d was assigned the job of making a formal reply on behalf of the editors of the Universalist Magazine. As he was known to be open and reliable, and a believer in future punishment, amongst the three editors he would be the one perceived to be most even-handed. His editorial, accusing Dean and Turner of professional envy of his great-uncle, was devastating to the Restorationist cause and put the ministers who had authorized the “Appeal and Declaration,” on the defensive. As they elected not to make a public reply, Ballou 2d’s verdict was allowed to stand.

Throughout the controversy Ballou 2d attempted to mediate the differences between the two sides, believing that the conflict was based more on personalities than on theologies. When in 1831 a group of Restorationists left the Universalist fold and formed the Massachusetts Association of Universal Restorationists (MAUR), he commented that the New England Universalist General Convention “now counts among its members, as it ever has done, more Restorationists than belong to that party that seems to identify all its movements with that appellation.”

Ballou 2d was at heart no theological controversialist. Basically an educator and historian, he participated in the Restorationist controversy only when he felt it necessary to set the record straight. When he did write theologically, it was in a scholarly manner and in the spirit of teaching rather than debate. His Biblical criticism, such as “The New Testament Doctrine of Salvation,” in the Expositor, 1840, helped Universalists return to the theology repudiated by his great-uncle during the Restorationist controversy.

Ballou 2d was an active participant in Universalist conventions and associations. At the New England General Convention, which he attended most years from 1816 on, he served as moderator and clerk, on the Seminary Committee, and on various fellowship, disciplinary, and constitutional committees. He was chosen Standing Clerk in 1824 and served the New England General Convention and its successor, the United States General Convention, until 1839. He was also, beginning in 1824, Standing Secretary of the Southern Association.

In 1829, after four and a half years of research, Ballou 2d published The Ancient History of Universalism, from the Time of the Apostles to the Fifth General Council, a comprehensive study that gave Universalists some scholarly recognition and helped to demonstrate that their heresy, if such it was, had a venerable lineage. There was an appendix which in outline fashion brought the story of belief in universal salvation to just before the Reformation. The scholarship held up a long time; new editions appeared in 1842 and 1871.

In the earliest days of the Christian Church, Ballou 2d argued, there was little that could be described as a system of doctrine. Nothing was asked of early converts, except acknowledgment of the mission of Christ and a life that reflected their simple profession. According to Ballou’s narration, during the first century little was said about the afterlife and for centuries after that time diverse opinions were openly held. It was only around AD 400 that Universalism began to be censured. According to Ballou 2d, church and civil politics—not the divine ordinance or early Christian teaching—established the heresy of belief in universal salvation.

During his years in Roxbury and Medford Ballou taught and advised a number of students preparing for the ministry, among them two of his brothers, Levi and William Starr Ballou, and a distant cousin Russell A. Ballou. Other students included Thomas Starr King, Edwin Hubbell Chapin, Charles Spear, John Murray Spear, Matthew Hale Smith, and George Bradburn. He recruited Adin Ballou to the Universalist ministry. To broaden the education of self-taught ministers Ballou developed a three-year home study curriculum, Course of Biblical and Theological Study, 1839. By 1840 so many students hoped to study under him that he began to teach them in groups at specified class times, rather than individually.

Ballou 2d was long interested in establishing Universalist academies, colleges, and theological schools. Many established ministers, including the elder Hosea Ballou, were opposed to the institutions for the training of clergy, convinced that a good knowledge of the Bible and a good mentor were all that were needed for the preparation of a minister. Moreover they suspected that a seminary education would expose the students to undue orthodox influence. In “Review of the Denomination of Universalists in the United States,” Universalist Expositor, 1839, Ballou 2d tried to assuage these fears. He compared the beliefs and behavior of the clergy in sects that had recently founded theological schools and discovered that “they have grown more liberal in doctrine, and less aristocratic and domineering, less confined to one form of words and one manner of speaking and thinking.” The report was much reprinted and influenced the institution-building of the new generation of Universalists.

Feeling the need of more scholarly Universalist journals than were then available, Ballou 2d founded and edited the Universalist Expositor, 1830-40, a bi-monthly with 6 volumes over 10 years. As it had a smaller circulation than general periodicals it generally lost money. Several times discontinued, it was twice revived by Ballou 2d, and continued to be a financial drain until the publisher in 1840 protested, “The Expositor must stop!” Later Ballou 2d edited the Universalist Quarterly and General Review, 1844-56. This magazine contained scholarly articles mixed with pieces of more general interest. He wrote many articles on Biblical, theological, historical, literary critical, philological, and biographical topics. He was the first president of the Universalist Historical Society, serving 1834-35 and in 1846. The Universalist leader and historian Elbridge G. Brooks termed him “probably the most learned theologian in the ranks of self-educated men in the country.”

In 1843, to fill the vacancy created by the death of William Ellery Channing, Ballou 2d was appointed to the Harvard Board of Overseers, a position he held until 1858. In 1845 he received a D.D. degree from Harvard, the first Universalist so recognized.

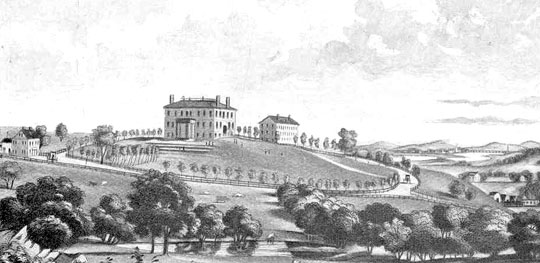

Beginning in 1841 Ballou 2d worked tirelessly in an effort to establish a Universalist college. In that year Charles Tufts, a Charlestown, Massachusetts Universalist, donated ten acres on a hill in Medford upon which to build a seminary. Ballou 2d helped to raise funds, but, partly due to the opposition of the elder Hosea Ballou, the effort fell considerably short of what was needed. Ballou 2d’s Occassional Sermon before the General Convention of 1847, “The Responsibilities of Universalists in the Position They Now Hold before God and the World,” inspired the educational convention held two days later to initiate a new fund-raising campaign for a Universalist college. After four years sufficient funds had been raised to proceed. To Ballou 2d’s disappointment, Medford was selected as the site; he feared that its location so near to Cambridge would mean that it would always be overshadowed by Harvard.

In 1853 Ballou reluctantly agreed to serve as president of the new school and in 1855 Tufts College officially opened. Ballou himself carried a heavy load, teaching history and intellectual philosophy in addition to his presidential duties and conducting the majority of chapel and Sunday services. According to College records, he “gave instruction in history remarkable alike for its quantity and quality, at a time when the study was hardly recognized in American colleges.”

Death

Four years later Ballou’s health began to fail, necessitating a reduction in his responsibilities. By the time Ballou died quietly at his College home in 1861, Tufts College had been well established. The importance of his work there was increasingly appreciated after his death. A history of the college, published in 1896, included this tribute: “Modest and unassuming in his manners, the influence of his character was felt by all who knew him. He was worthy to be called by that most honorable of titles,—a cultured Christian gentleman.”

Hosea and Clarissa Ballou had seven children, two of whom died young. At least four were Universalists. The eldest, Giddings Hyde Ballou (1820-1886), was a painter, writer of illustrated articles for Harper’s, and an editor of the Gospel Banner. Harriet Eliza (1830-1859) married Universalist minister Russell A. Ballou. Two unmarried daughters, Julia Crehore (1828-1883) and Mary Jane (1833-1885) were longtime members their father’s church in Medford.

Sources

Hosea Ballou 2d’s sermons and correspondence are in the Universalist Special Collections at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts and in the Tufts University Archives in the Wessell Library, Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts. Among his works not mentioned above are a number of printed sermons and tracts, A Collection of Psalms and Hymns for the Use of Universalist Societies and Families (1837), and Counsel and Encouragement: Discourses on the Conduct of Life (1866). The most substantial source of information on Ballou 2d is Hosea Starr Ballou, Hosea Ballou 2d, D.D., First President of Tufts College: His Origin, Life, and Letters (1896), which contains excerpts from his correspondence and a catalogue of his scholarly journal articles.

Among the biographical essays on Ballou 2d are Elbridge Gerry Brooks, “Hosea Ballou 2d,” Universalist Quarterly and General Review (July 1878) and Russell Miller, “Hosea Ballou 2d: Scholar and Educator,” Annual Journal Universalist Historical Society (1959). There is a substantial entry on Ballou 2d and entries on his grandfather, his father, and his children in Adin Ballou, An Elaborate History and Genealogy of the Ballous in America (1888) and an entry by Alan Seaburg in American National Biography (1999). There is also biographical information in Richard Eddy, Universalism in America, vol. 2 (1886); Alaric B. Start, ed., History of Tufts College (1896); Inventory of Universalist Archives in Massachusetts (1942); Russell Miller, Light on the Hill, A History of Tufts College, 1852-1952 (1966); Edith Fox McDonald, Rebellion in the Mountains: The Story of Universalism and Unitarianism in Vermont (1976); and Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, vol. 1 (1979).

Article by Charles A. Howe and Peter Hughes

Posted October 5, 2003