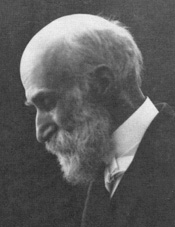

William Sullivan Barnes (June 16, 1841-April 2, 1912), an outstanding preacher, was for thirty years minister of the Church of the Messiah (Unitarian) in Montreal. A liberal Christian, his sermons reflected the most advanced thinking of his day. Yet his distinctive reputation is best conveyed by the word “saintly”. His friends had to rescue him from his impractically saintly behaviour, such as repeatedly giving away his overcoats to people he thought needed them more than he did in a Montreal winter. His successor in the pulpit, Frederick Griffin, said, “There was that about Dr Barnes’s bodily presence which was ethereal. I understand that as a young man he gave the same impression of being almost incorporeal.”

William Sullivan Barnes (June 16, 1841-April 2, 1912), an outstanding preacher, was for thirty years minister of the Church of the Messiah (Unitarian) in Montreal. A liberal Christian, his sermons reflected the most advanced thinking of his day. Yet his distinctive reputation is best conveyed by the word “saintly”. His friends had to rescue him from his impractically saintly behaviour, such as repeatedly giving away his overcoats to people he thought needed them more than he did in a Montreal winter. His successor in the pulpit, Frederick Griffin, said, “There was that about Dr Barnes’s bodily presence which was ethereal. I understand that as a young man he gave the same impression of being almost incorporeal.”

William Barnes was born in Boston, the son of Lydia Ann Yetton and Baptist minister William H. Barnes. In 1864 he married Mary Alice Turner and in the same year was ordained to the Baptist ministry in Melrose, Massachusetts. His increasingly liberal theology and invitations to open communion led him in 1868 to leave the Melrose church and withdraw from Baptist fellowship. He preached to Unitarians, Baptists and others in a rented hall for a few weeks, and then accepted a call to the local Unitarian parish church, renamed the Liberal Christian Congregational Society. Although popular in his new church, Barnes felt so uncomfortable living in such proximity to his aggrieved former parishioners that he left after five months. He then served the Unitarian church in Woburn, Massachusetts, 1869-79. In 1879 he went to Montreal as a short-term interim minister and made such a positive impression that he was promptly invited to settle.

Barnes was handicapped by shyness and by physical frailty. He suffered from asthma, and on a number of occasions the congregation had to find a pulpit replacement on short notice. Yet a personal magnetism drew people to his preaching services. He was much in demand as well in other settings of the city for the lectures he readily gave on modern thought, art and literature. Barnes accepted Darwinian evolution, other new scientific theories, and higher criticism of the Bible. His positions on such matters would have made a more confrontational personality a storm-centre of controversy, but Barnes could present ideas in a way that disarmed hostility. The congregation gratefully noted in its annual report for 1885, “Whilst speaking the truth as he sees it boldly and clearly, not a word has ever escaped his lips that would . . . hurt the feelings of any who might differ from us in belief.”

Barnes’s favourite theologian was James Martineau. “The supreme authority is the voice of God within us,” Barnes wrote. “But we are not always ready to hear that voice; . . . hence the value of outward examples who reveal to us the facts of spirit and by their fervour raise us from what is low, helping us to listen to the inward calls which they have heard. . . . It is as the example, outwardly presented as the story, inwardly perceived as the enthroned ideal, that the Unitarian loves and honours Christ. . . . We imitate the Master when we do that which falls to us in the spirit and by the principles in which he fulfilled his trust.”

In its annual report for 1886 the congregation acknowledged, “[W]e recognize more and more in the uprightness and unselfishness of his life the illustration and interpretation of that pattern life he so eloquently sets before us in his words.”

Beyond his focus upon spirituality in one’s personal living, Barnes’s successive interests were actualized in the careers of his sons. Howard Turner Barnes (1873-1950), a physicist, specialized in the study of the properties of ice. He sought practical techniques for preventing and breaking up river ice jams. A fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and of the British Royal Society, he delivered the 1912 Tyndall Lectures at the Royal Institute in London, “Ice Formation in Canada: Physical and Economic Aspects.” He succeeded Ernest Rutherford as Macdonald Professor of Physics at McGill University, 1908-33. Wilfred Molson Barnes (1882-1955) was equally distinguished as a landscape painter and an art teacher. He studied in Montreal and New York and was a member of the Royal Canadian Academy. Three of his paintings are in the National Gallery of Canada. Howard practised for years private morning devotions written for him by his father; he published these in 1925.

As time went by, William S. Barnes was in ever-greater demand as an interpreter of poetry and the visual arts. Upon his retirement in 1909, McGill University awarded him an honorary LL.D. The citation spoke of “his attainments in arts and letters, his active interest in the diffusion of culture and his devoted services to all that concerns the spiritual life of the community.”

When Barnes died, a Montreal newspaper noted, “Of the propagandist he had not a particle in his methods or nature.” But, though esteemed by many, his work in the arts did not build membership in his church. Few of those who flocked to hear him joined the congregation, which during his pastorate diminished to little more than a third its size when he arrived. In the last few years of his ministry, he successfully oversaw construction of a beautiful new church building. It was everything he thought a place of worship should be. His obituary concluded, “The name of Dr Barnes will long be remembered in Montreal as worn by a scholar, an artist and poet in one; a really great preacher . . . and chiefly perhaps as a considerate, noble Christian gentleman.”

The minute-books of the Church of the Messiah, Montreal, a scrapbook containing newspaper clippings about Barnes, transcriptions of several Barnes sermons, and manuscript histories of the congregation are in the archives of the Unitarian Church of Montreal, Quebec. There are a very few letters in the Unitarian Universalist Association Archives in Boston, Massachusetts. Barnes wrote the article on Unitarianism in Canada in An Encyclopedia of the Country (1898). Howard Turner Barnes wrote a number of books on water and ice, including On Some Measurements of the Temperature of the Lachine Rapids (1898), Ice Formation (1906), Icebergs and Their Location in Navigation (1913), Thermit and Icebergs (1927), and Ice Engineering (1928).

Published sources of information on Barnes include George H. Dearborn, Historical Sketch of the Unitarian Church of Melrose, Mass. (1900); Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith, Vol. 4 (1952); Charles W. Eddis, ed.: A Century and a Half (1992); E.A. Collard et al, Montreal’s Unitarians, 1832-2000 (2001); and Phillip Hewett, “William Sullivan Barnes”, in The Dictionary of Canadian Biography (1998). Material on Barnes’s sons is found in the Canadian Encyclopedia, the Dictionary of Canadian Artists, and Obituary Notices of Fellows of The Royal Society (November 1952).

Article by Phillip Hewett

Posted January 8, 2003