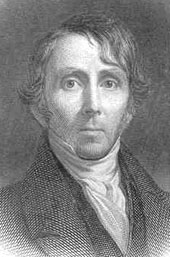

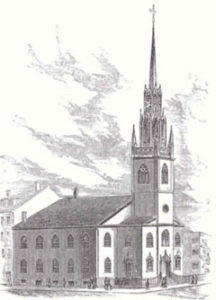

William Ellery Channing (April 7, 1780-October 2, 1842), minister of the Federal Street Church in Boston, Massachusetts, 1803-42, was a spokesman during the Unitarian controversy for those liberal—or Unitarian—churches within Massachusetts’ Standing Order of churches. His published sermons, lighting a path between orthodoxy and infidelity, were widely influential abroad as well as throughout the United States. His Christian humanism inspired both religious and literary features of the Transcendentalist movement. An exemplar of Christian piety and a champion of human rights and dignity, he effectively fostered social reform in areas of free speech, education, peace, relief for the poor, and anti-slavery. His pulpit orations made him, according to Emerson, “a kind of public Conscience.”

William was born to a prosperous and distinguished family in Newport, Rhode Island, the third child of William and Lucy Ellery Channing. His mother’s father, William Ellery, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, as Newport’s Federal Customs Collector commanded the search and seizure of suspected slave trade vessels after the United States Congress in 1794 passed the Act prohibiting the trade. His father, Rhode Island Attorney General and a United States District Attorney, defended the first slaver to be convicted in an American court. One of his brothers, Walter Channing, became a prominent physician and another, Edward Tyrrell Channing, Boylston Professor of Rhetoric at Harvard.

When William was growing up, Newport, founded by Baptists on the principle of religious freedom, had Baptist, Congregationalist, Quaker, Independent and Jewish houses of worship. Newport’s large African population attended their masters’ churches, but practiced their own funeral traditions. Slaves of Channing family households were leaders in the African community. Duchess Quamino, William’s black nanny, and Newport Gardner, owned by an uncle, taught him that integrity is the essence of religion.

Before William’s birth the Channing family had attended Newport’s Second Congregational Church, whose minister, Ezra Stiles, was a close friend of William’s grandparents, John and Mary Channing. Along with John Channing, Stiles was among the Newport Sons of Liberty. As many Congregationalist ministers did during the revolutionary period, Stiles advocated republican values without fully considering their consistency with orthodoxy. Channing once said he owed to Ezra Stiles the indignation he felt “at every invasion of human rights.”

Following the British occupation Stiles assumed the presidency of Yale College. For a time, while it was the only Congregational church open, William’s family attended First Congregational whose minister, Samuel Hopkins, was a disciple of Jonathan Edwards. Although he was a divine of some stature, Hopkins’s preaching did not appeal to young Channing. As an adult he described Hopkins’ harsh theology as “stern and appalling.” Yet he never forgot that it was Hopkins who brought slavery to his attention when he was 12.

One Sunday William’s father took him to hear an itinerant preacher. Overwhelmed by the fiery sermon, William felt “a curse seemed to rest on the earth and darkness and horror to veil the face of nature.” His father’s remark at the sermon’s end—”Sound doctrine that!”—led the boy to expect that upon reaching home they must fall on their knees and pray for deliverance from impending doom. Instead, the family ate their usual meal, and then his father sat by the fire, puffed his pipe and read the newspaper. The boy concluded he should not take so seriously what people said, but study their behavior to know what they meant. But it would take him many years to be rid of his “early gloom” regarding religion.

In 1792 William was sent to study with his uncle, Henry Channing, a liberal minister in New London, Connecticut. At age 15 he entered Harvard College. His college reading of Francis Hutcheson, a Scottish common sense philosopher, was transforming. The Calvinist doctrine of original sin divided humanity into the “redeemed,” within whom God’s grace had planted a “new sense” that enabled the heart to know true virtue, and the “unredeemed” whose virtues could be no better than self-serving. Hutcheson asserted a universal human capacity for unselfish benevolence. Reading Hutcheson, Channing apprehended, with the force of an epiphany, the dignity of human nature, the vital principle of human rights.

Channing graduated from Harvard at the head of the class of 1798. Needing an income to continue his studies, he served as tutor for the children of David Meade Randolph of Richmond, Virginia. In Richmond the young man was appalled by much of what he learned of Southern slavery and society, and he permanently weakened his health with ascetic practices. At some point in Richmond, he also experienced a “change of heart” and wrote to his uncle, “I have now solemnly given myself up to God.”

Channing returned to Newport in 1800 and had a series of conversations with Hopkins. Although he still found repugnant much of Hopkins’ avowed theology, Channing was much taken by his “theory of disinterestedness.” It seemed to him that Hopkins actually lived these generous principles. He later recalled, “I had studied with great delight during my college life the philosophy of Hutcheson, and the Stoic morality, and these had prepared me for the noble, self-sacrificing doctrines of Dr. Hopkins.”

For Channing contemplation of God’s mighty works at Newport beach made hime feel exhilarated to be part of nature. In 1836 he told the Newport Unitarian congregation, “No spot on earth has helped to form me so much as that beach. There I lifted up my voice in praise amidst the tempest. . . . There, in reverential sympathy with the mighty power around me, I became conscious of power within.”

In 1801 his appointment as a regent, or student supervisor, at Harvard allowed Channing to study for the ministry under Prof. David Tappan. During this period Channing wrote down some thoughts which guided him in his studies throughout his life, defining his liberal bent: “It is always best to think first for ourselves on any subject, and then to have recourse to others for the correction or improvement of our own sentiments. . . . The quantity of knowledge thus gained may be less, but the quality will be superior. Truth received on authority, or acquired without labor, makes but a feeble impression.”

In 1802 Channing was licensed to preach by the Cambridge Association. The following year Boston’s Federal Street Church called and ordained him. Tappan preached the ordination sermon, his uncle Henry Channing gave the charge, and his Harvard classmate and friend Joseph Tuckerman extended the right hand of fellowship. Channing served on the board of the Harvard Corporation, 1813-26, and worked toward the 1816 establishment of the Harvard Divinity School.

In 1814 Channing married a first cousin, Ruth Gibbs, one of the wealthiest women in the country. He upheld a woman’s right to own property and never claimed his wife’s money, as the law of the time allowed him to do. They had four children. His son, William Francis Channing, designed Boston’s citywide fire alarm system, the nation’s first.

For some time dissension had been brewing among New England Congregationalists. The Unitarian controversy had begun in 1805 with a struggle—which the liberals won—over the appointment of a successor to Channing’s Harvard mentor, David Tappan. Always reluctant to be divisive, Channing did not speak publicly about the controversy until 1815. The Rev. Jedediah Morse, looking to call attention to liberal tendencies in Congregationalism, had reprinted a chapter on American Unitarianism from the British Unitarian Thomas Belsham’s Life of Theophilus Lindsey. A review of Morse’s reprint in an orthodox magazine, The Panoplist, charged New England’s liberal ministers with secretly sharing Lindsey’s Socinian views, although they hid them from church members. Channing wrote a reply, addressed to a liberal colleague and titled, A Letter to the Rev. Samuel C. Thacher on the Aspersions Contained in a Late Number of the Panoplist, on the Ministers of Boston and the Vicinity, 1815. He denied that liberal ministers were Socinian, but went on to describe the subtleties of Trinitarian doctrine as of little use in the minister’s work of inspiring people to lives of Christian love. Channing’s Letter immediately and publicly identified him as a spokesperson for liberal congregations and their ministry.

A few years after Channing’s Letter it was clear that Unitarians would be a separate communion. To his and many Unitarians’ sorrow, the broad fellowship—shared among churches of the Standing Order since Colonial times—was rent asunder by the refusal of orthodox ministers to exchange pulpits with Unitarian Christian ministers. In 1819, to make clear the liberals’ theology in a time of conflicting reports, Channing delivered a landmark sermon, Unitarian Christianity, at the ordination by the new First Independent Church in Baltimore of Jared Sparks. Tens of thousands of copies were sold.

In Unitarian Christianity Channing described the Bible as “a book written for men, in the language of men” whose “meaning is to be sought in the same manner as that of other books.” He defended the use of reason in religion. “If reason be so dreadfully darkened by the fall, that its most decisive judgments on religion are unworthy of trust, then Christianity, and even natural theology must be abandoned; for the existence and veracity of God, and the divine original of Christianity, are conclusions of reason, and must stand or fall with it.”

Channing then lifted up conclusions from a reasoned study of the scriptures. He said that nowhere does the New Testament’s word for God mean three persons; that so confusing a doctrine as the Trinity distracts the mind from communion with God; and that in effect the doctrine of predestination “makes of men machines.” The whole purpose of Christ, he preached, was “to call forth and strengthen piety in the human breast.” He expanded on this topic in a sermon titled “Unitarian Christianity Most Favorable to Piety,” 1826. There, criticizing the Trinitarian doctrine of vicarious atonement, he said, “It does not make the promotion of piety [Christ’s] chief end. It teaches, that the highest purpose of his mission was to reconcile God to man, not man to God.”

Channing fervently believed God had made human nature, with its capacity for moral choice and ever increasing understanding, akin to the divine. He confidently preached the possibility of unending moral and spiritual progress for all who would shape their lives in accordance with its demands. He said in his 1830 Election Day sermon, “Spiritual Freedom,” “I call that mind free which masters the senses, which protects itself against animal appetites, which contemns pleasure and pain in comparison with its own energy, which penetrates beneath the body and recognizes its own reality and greatness. . . . I call that mind free which escapes the bondage of matter, which, instead of stopping at the material universe and making it a prison wall, passes beyond it to its Author.”

Thus far in his sermon he had expressed sentiments as much appreciated by the orthodox as by liberals in his audience. But Channing went on to pronounce a spiritual and intellectual manifesto which voiced the germ of Emerson’s 1838 Divinity School Address and, indeed, the Transcendental movement. “I call that mind free which jealously guards its intellectual rights and powers, which calls no man master, which does not content itself with a passive or hereditary faith, which opens itself to light whencesoever it may come, which receives new truth as an angel from heaven, which, while consulting others, inquires still more of the oracle within itself.”

Channing many times urged that we begin to understand God by looking inside ourselves. He wrote in “Likeness to God,” 1828, “Our own moral nature” leads us to comprehend God through its “approving and condemning voice. . . . The soul, by its sense of right, or its perception of moral distinctions, is clothed with sovereignty over itself, and through this alone, it understands and recognizes the Sovereign of the Universe.”

Channing’s synthesis of piety and human rights, a middle way between Enlightenment discourse and Christian orthodoxy, is woven about this point of the supreme worth of human personality. The warp and woof of this fabric are not without tension. For Channing, the tensions were existential. “God’s sovereignty is limitless; still man has rights.” If these are antagonistic ideas, yet both are true. “The worst error in religion” arises from neglect of one or the other. The power of Channing’s eloquence was greatly enhanced by his presence, in the pulpit and elsewhere. It was as though people could feel directly his benign sincerity. Frederic Henry Hedge said Channing could “send his word into the soul with more searching force than all the orators of his time.” Theodore Parker spoke, with reference to Channing, of a “moral power that spoke in him; which spoke through him.”

From his earliest days in ministry, Channing was concerned for the education and spiritual progress of children. One of the earliest innovations of his ministry was to invite the children about him after worship. This was one of a number of examples of his creating small discussion groups for church members which emerged as part of the Sunday School movement. In 1813 he worked with Samuel Cooper Thacher of the New South Church to produce a catechism for the use of the children in the two churches. His first published sermon was “The Duties of Children,” 1807. He worked with educational reformers Elizabeth Peabody, Bronson Alcott, Dorothea Dix and Horace Mann. He wrote in his “Remarks on Education,” “There is no office higher than that of a teacher of youth, for there is nothing on earth so precious as the mind, soul, character of the child.”

Like many in New England, whose economy depended on maritime trade, Channing opposed the War of 1812. He vigorously defended the right to criticize the war, saying a republican government secures its citizens’ right to vote and to discuss their rulers. “Freedom of opinion, of speech, and of the press is our most valuable privilege, the very soul of republican institutions, the safeguard of all other rights.” If the cry of war meant “all opposition should therefore be hushed,” there would be no impediment to “war without end.”

In 1815, at Channing’s invitation, Noah Worcester held a meeting at the Federal Street parsonage. Those attending formed the Peace Society of Massachusetts, the first of numerous “societies” founded in Channing’s study.

For nearly twenty years Channing was the Federal Street Church’s active parish minister. In 1824 he took a young associate, Ezra Stiles Gannett. From the first Channing extended trust and pulpit freedom to his associate. In 1825 Channing wrote Gannett that his health would “oblige me to throw on you this next year & probably afterwards a large part of the care of our parish.” Wishing to benefit Gannett, Channing periodically arranged for his own salary to be reduced.

In 1822-23 Channing had traveled to England and continental Europe for the sake of his frail health. The trip did little by way of improving his health, but it stimulated his literary interests. Returned from Europe, he penned several essays, all highly acclaimed, on Milton, 1825; Fenelon, 1829; and Napoleon Bonaparte, 1828-29. These, the first American essays written in the grand tradition of judicial criticism, caught the attention of British reviewers and established Channing’s literary work as worthy to be discussed along with Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas Carlyle.

In 1823 he delivered, before the American Philosophical Society, “Remarks on National Literature.” Here Channing expressed disappointment with the literary culture of democratic America. “The great distinction of a country,” he wrote, “is that it produces superior men.” Great institutions he described as having no value, except as a medium for inward growth. “The great hope of society is individual character.” Unfettered by tradition, Americans had a unique opportunity to add to humanity’s self-knowledge through the creation of a new literature.

Channing was ambivalent about money. He owed his financial independence and some of his social standing to his wife’s fortune, yet was frequently driven by his faith and conscience to make social and political stands that offended both the Gibbs and the Channings. In 1835 he wrote to Lucy Aiken of the house he was building next to the Gibbs mansion. He said he spent nothing on amusements and little on clothing, but that he must have a good house, “open to the sun and air, with apartments large enough for breathing freely.” On thinking of the millions living in “outward and inward destitution,” he acknowledged it was “hard to realize our conceptions of disinterested virtue!” In 1842 he wrote a friend deploring “the spirit of rapid accumulation” which he considered in opposition to “the spirit of Christianity.” He did not think revolution likely, however, but trusted in the liberal principles of the emerging middle class.

Although his family exploited the free labor market, Channing was deeply concerned about the destiny of displaced and low wage workers. In 1826 he proposed to the Wednesday Evening Association, a charitable society he had helped found, a ministry to the poor of Boston’s docks. Joseph Tuckerman took up the call. In 1834 the Benevolent Fraternity of Churches in Boston was formed to support Tuckerman’s and others’ ministries.

Channing conceived spiritual awakening to be required for economic development in the circumstances of a free labor market. His lecture, Self-Culture, 1838, was addressed to working artisans. He tried to inspire them with his vision of their potential. He told them politics, education, art and literature could all be means of their development and prosperity. Self-culture is the practice of likeness to God. Any notion that the majority of human beings, all with a moral nature, were created only to “minister to the luxury and elevation of the few,” violates the universality of human rights.

Among those critical of Channing’s concept of self-culture was Orestes Brownson, who had converted to Unitarianism upon reading Channing’s “Likeness to God.” But he had come to see Channing’s constant emphasis on the individual as inadequate to the need for social reform. He wrote in The Laboring Classes, 1840, “Self-culture is a good thing, but it cannot abolish inequality, nor restore men to their rights. As a means it is well, as an end it is nothing.”

Even so, Channing had a hand in starting many ongoing organizations, among them the Berry Street Conference, a meeting of liberal ministers he summoned in 1820, and which has convened annually ever since. He feared large organizations and was unwilling in 1825 to take any part in forming of the American Unitarian Association, a missionary organization which would seek support from the liberal churches. He said there is “no moral worth in being swept away by a crowd, even towards the best objects.” He labored, not to generate institutions, but earnestness. In his “Remarks on Associations,” 1829, Channing described the church, the family and the state as natural institutions; others worked unneeded mischief. He formulated the Iron Law of Oligarchy: the “tendency of great institutions to accumulate power in a few hands.” He believed large associations “tend to produce dependence, and to destroy self-originated action in the vast multitudes who compose them.”

The Transcendental Club, which included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, Orestes Brownson and others, was organized by George Ripley on a suggestion by Channing. But Channing attended few meetings because he felt those in attendance might defer to him rather than speak their own minds. He did nevertheless participate in another discussion group which included Alcott, Hedge, and Ripley.

Channing feared for the often fiery young men of the Unitarians’ second generation of ministers, who—following Emerson—would discard wholesale their own churches’ liberal Christian tradition. In its place they embraced an “absolute” religion whose moral demands they intuitively perceived to “transcend” all history. These younger ministers and other “Transcendentalists” called for the radical restructuring of society, and also publicly subjected Unitarians any less passionately committed to social reform than themselves to withering criticism. Ever one to avoid conflict if possible, Channing did not publicly criticize the Transcendentalists. In fact he had “far more sympathy with them,” according to James Freeman Clarke‘s account of an 1841 conversation, than with self-satisfied and apathetic “technical Unitarians.” At least men like Emerson and Theodore Parker had the moral earnestness the times called for.

Emerson, though not uncritical of Channing’s caution, told Peabody, “In our wantonness we often flout Dr. Channing, and say he is getting old; but as soon as he is ill we remember he is our Bishop and we have not done with him yet.”

Channing spoke against slavery as early as 1825. An 1830 trip to the West Indies, in search of health, again provided him with a vivid view of the injustice and cruelty of slavery. He was impressed by Lydia Maria Child‘s Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans, 1833, and immediately engaged her in a series of long conversations. “I owe him thanks,” she later wrote, “for preserving me from the one-sidedness into which zealous reformers are so apt to run. He never sought to undervalue the importance of Antislavery, but he said many things to prevent my looking upon it as the only question interesting to humanity.”

A number of his protégées worked with William Lloyd Garrison’s anti-slavery movement, among them Samuel J. May. When Channing lamented the abolitionists’ unhelpful inflammatory language, May asked, “Why sir, have you not taken this matter in hand yourself?” Channing acknowledged the justice of May’s reproach and, in 1835, published Slavery. In this he claimed, as he had many times, that human rights derive from our moral nature, created by God, not society. Slavery, he thought, calls for an examination of “the foundation, nature, and extent of human rights.” He went on to say that to enslave a person is an insult to God. He said the sin of slavery thwarts the spiritual progress of slaves and slave owners, but he condemned the sin, not sinners. Garrison was disappointed by such moderate anti-slavery. He denounced Channing’s book as “utterly destitute of any redeeming, reforming power.”

The Massachusetts Attorney General, James T. Austin, and the Boston industrialists who sat in pews of the Federal Street Church, disapproved his book on opposite grounds. Austin said Channing was encouraging slave insurrection. In 1840, Channing’s dear friend, Unitarian and abolitionist minister Charles Follen, died in a maritime disaster. Channing preached one of his finest sermons on his death. Soon after, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society asked, with Channing’s support, if a memorial service for Follen might be held at the Federal Street Church. The Standing Committee said no, it could not be. Thereupon Channing wrote to the Standing Committee, “If it should be thought best that there should be a formal dissolution of the relation, I desire that this may immediately take place.” No dissolution transpired, but thereafter Channing preached only once from the Federal Street pulpit.

Channing had more than twenty years earlier closed Unitarian Christianity with a petition envisioning Christ as a messianic Son of Liberty, “that He will overturn, and overturn, and overturn the strongholds of spiritual usurpation, until He shall come whose right it is to rule the minds of men.” In his later thinking Channing mediated on usurpations that went beyond those of churches. His most impassioned antislavery publication, The Duty of the Free States, 1842, refutates Daniel Webster’s legalistic rhetoric about necessity of obeying the slave laws of the United States. “No decision of the state absolves us from the moral law,” Channing argued. “It is no excuse for our wrong-doing that the artificial organization called society has done wrong.”

Channing’s last public address, in Lenox, Massachusetts, on August 1, 1842, celebrated the anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies and called for an end to slavery in the United States using similarly peaceful means. His moderate and considered support gave anti-slavery a respectability it had not previously possessed.

When Channing died in 1842 many paid tribute to his ministry. May said Channing sacrificed his serenity and reputation “by espousing the cause of the oppressed.” Gannett mourned that “the Age has lost one of its brightest lights, the world one of its true benefactors.” Parker said, “No man, of our century, who writes the English tongue, had so much weight with the wise and pious men who speak it.”

In his lifetime and long after it, Channing was the most influential American religious leader whose works were known beyond America. His books, translated into many languages, traveled the world and were read attentively by Alexis de Tocqueville, Ernest Renan, Hajom Kissor Singh, John Stuart Mill, Max Weber, Krizna Janos, and Queen Victoria. Among Unitarians Channing was claimed by Transcendentalist radicals as well as by their critics, who often styled themselves “Channing” Unitarians.

Keen interest in Channing continued throughout the 19th century. He was neglected during the tumultuous first half of 20th century. Students of American religion have since shown a renewed appreciation of him. Pioneering a middle way between spirituality and secularity, Channing was a subtle and key figure in American religious and literary history. As David Robinson put it, he “reconceived the model of the religious life which he inherited from New England theology, and did it so completely that [he] changed the intellectual landscape of early nineteenth-century America.”

Channing papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, Massachusetts; the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts (including Federal Street/ Arlington Street Church records); the Houghton Library of Harvard University; and the Meadville/Lombard Theological School Library in Chicago, Illinois. Channing’s Works, published in 1843 in 6 volumes were issued, beginning in 1875, in one large volume. Other sermons were printed by William Henry Channing in The Perfect Life (1873). David Robinson, William Ellery Channing: Selected Writings (1985) is a modern anthology. Charles Lyttle’s The Liberal Gospel (1925) is a thematic arrangement of short excerpts from Channing’s writings.

Memoirs and biographies of Channing include William Henry Channing, Memoir of William Ellery Channing (1848); Anna Letitia LeBreton, ed., Correspondence of William Ellery Channing and Lucy Aikin, from 1826 to 1842 (1874); Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Reminiscences of Rev. William Ellery Channing (1880); Charles Timothy Brooks, William Ellery Channing: A Centennial Memory (1880); Russell Nevins Bellows, ed., The Channing Centenary in America, Great Britain, and Ireland: A Report of Meetings Held in Honor of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of William Ellery Channing (1881); John White Chadwick, William Ellery Channing, Minister of Religion (1903); Jabez T. Sunderland, The Story of Channing (1921); Arthur W. Brown, Always Young for Liberty: A Biography of William Ellery Channing (1956); Madeleine Hooke Rice, Federal Street Pastor (1961); and Jack Mendelsohn, Channing: The Reluctant Radical (1971). Among the many biographical articles and entries on Channing are those by William B. Sprague in Annals of the American Unitarian Pulpit (1865); Samuel A. Eliot in Heralds of a Liberal Faith, vol. 2 (1910); David Robinson in Joel Myerson, ed., The Transcendentalists: A Review of Research and Criticism (1984); Daniel Walker Howe in American National Biography (1999); and David Robinson, in Dictionary of Literary Biography Volume 235 (2001). The latter has a list of all of Channing’s works.

Studies of Channing include Robert Leet Patterson, The Philosophy of William Ellery Channing (1952); David P. Edgell, William Ellery Channing: An Intellectual Portrait (1955); Andrew Delbanco, William Ellery Channing: An Essay on the Liberal Spirit in America (1981); and Frank Carpenter, “He Stood Alone,” The Unitarian Universalist Christian (1994). Channing is a central figure in Daniel Walker Howe, The Unitarian Conscience, Harvard Moral Philosophy, 1805-1861 (1970). Sydney E. Ahlstrom, “The Interpretation of Channing,” The New England Quarterly (March 1957) and Conrad Wright, “The Channing We Don’t Know,” in his The Unitarian Controversy (1994) are important reevaluations of Channing’s reputation.

For information on Channing’s Rhode Island background see Edwards A. Parks, Memoir of the Life and Character of Samuel Hopkins, D.D. (1854); George Gibbs Channing, Early Recollections of Newport, RI (1868); William M. Fowler, Jr., William Ellery: A Rhode Island Politico and Lord of Admiralty (1973); Jay Coughtry, The Notorious Triangle: Rhode Island and the African Slave Trade, 1700-1807 (1981); and Frank Carpenter, “Paradise Held: W. E. Channing and the Legacy of Oakland,” Newport History (1994). For information on the state of theology in America up to Channing’s generation, see Mark A. Noll, America’s God (2002).

Article by Frank Carpenter

Posted January 22, 2004