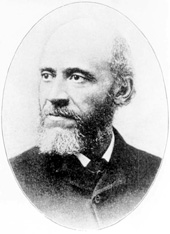

Peter Humphries Clark (March 29, 1829-June 21, 1925), an associate of Frederick Douglass, was one of Ohio’s most effective black abolitionist writers and speakers. The first teacher engaged by the Cincinnati black public schools and founder and principal of Ohio’s first public high school for black students, he was recognized as the nation’s foremost black public school educator. He was a path-breaking political activist who empowered black voters in Ohio electoral politics, a feat for which he was widely recognized, but which ultimately cost him his job.

Peter Humphries Clark (March 29, 1829-June 21, 1925), an associate of Frederick Douglass, was one of Ohio’s most effective black abolitionist writers and speakers. The first teacher engaged by the Cincinnati black public schools and founder and principal of Ohio’s first public high school for black students, he was recognized as the nation’s foremost black public school educator. He was a path-breaking political activist who empowered black voters in Ohio electoral politics, a feat for which he was widely recognized, but which ultimately cost him his job.

Peter was born in Cincinnati, his father Michael Clark a manumitted slave and his mother the mulatto daughter of an indentured servant from Ireland. His large extended family was active in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. In the absence of black public schools, his father—a successful barber—sent him to private schools. A brilliant student, he served as assistant teacher in the two lower grades of high school while he completed the remaining two. His father paid $200 to apprentice him to a white abolitionist maker of stereotype printing plates. Unfortunately this employer moved to California after two years, leaving Clark unable to find further work at this trade because of the color bar. After his father died in 1849, he briefly ran the barber shop, but hated serving white customers and quit.

Later that same year, largely due to the efforts of his uncle, John I. Gaines, “colored” schools were authorized by the Ohio legislature. Clark was hired as the first teacher. In 1853 he was fired by the white Board of Education as an “infidel” for having publicly praised the political and religious thought of Thomas Paine. African-Americans almost unanimously objected to the Board’s action.

During the next four years Clark was an abolitionist writer, speaker, editor and publisher. Along with his uncle, he participated in the Ohio Conventions of Colored Men. He edited and published his own weekly abolitionist paper, the Herald of Freedom. Despite being favorably reviewed by Frederick Douglass and other leading black abolitionists, the Herald went out of business after four months. Douglass appointed Clark secretary of the 1853 National Convention of Colored Men, and in 1856 he moved to Rochester, New York to serve as Douglass’s assistant on Frederick Douglass’ Paper (formerly the North Star). Clark, his wife—née Francis Ann Williams, an Oberlin graduate, whom he married in 1854—and their infant daughter lived with the Douglass family while Clark performed his editorial duties, gave abolitionist speeches throughout the midwest, and, as one of Douglass’ assistants, attended national abolitionist meetings. (The other was William James Watkins, cousin of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, the noted poet.) The Clark family returned to Cincinnati in 1857 when Clark was re-hired by the newly-empowered black trustees of the colored schools and made principal of the Western District School. Although he continued his abolitionist activities, and kept up his close relationship with Douglass until the latter’s death in 1895, his work as an educator quickly became his major preoccupation.

Clark was a strong supporter of his uncle, John I. Gaines, the secretary of the Board of Trustees of the colored schools and the major driving force for excellence in these schools. Both of them recognized the need for a high school to prepare the students for better jobs. In 1866 Clark convinced the board to establish a high school, comprising grades 7-12, with himself as principal. The school was named for the greatly beloved Gaines, who had died in 1859 at the age of 38.

For several years Clark had tutored promising students to prepare them to be teachers. He speedily established a normal department in the new John I. Gaines High School. Over the next twenty years virtually all the teachers hired by the colored schools of southwestern Ohio were trained at Gaines High. So well were they prepared that their marks on the Cincinnati Board of Education’s qualifying exams were equal to those of white applicants who took the same test. During the period 1868-89 a total of 158 students were graduated from Gaines High, a majority of them teachers. This does not count the many students who, before they had graduated, were hired by schools out of the area. More than half of the Gaines graduates (including all three of Clark’s children) stayed in Cincinnati, providing the city with a nascent black middle class which had a strong interest in equality of political and economic opportunity.

When Clark returned to Cincinnati in 1857, he became active in the new Republican Party. The local Republicans were led by Alphonso Taft and George Hoadly, both prominent attorneys and abolitionists who were members of First Congregational Church (Unitarian) of Cincinnati. The minister of the Unitarian Church was Moncure D. Conway, who had been fired from his Washington, D.C. pulpit for preaching abolitionist sermons. His well publicized liberal and abolitionist lectures and sermons, including a lecture in praise of Thomas Paine, must have appealed greatly to Clark. He joined the Unitarian Church in 1868, attracted by the Deist theological position espoused by its new minister, Thomas Vickers, and the access it gave him to powerful establishment leaders who were sympathetic to black aspirations.

Clark also maintained his ties to Allen Temple AME Church. From 1867-85 more than a score of articles in the Christian Recorder (the national weekly of the AME Church) mentioned or discussed Clark’s educational, political and charitable activities. He was a featured participant in the Allen Temple AME Church Semi-Centennial Celebration in 1874, speaking on “The Developing Power of African Methodism.” Articles by him were published in A.M.E. Church Review, the denomination’s national magazine of history and opinion. Neither of Clark’s two churches took note of the other. Apparently, each recognized that he needed both.

In 1871 Rev. Vickers, Clark, and another Unitarian layman represented the congregation at the National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches in New York City. Clark may have been the first black to represent a member church at a national Unitarian meeting. Clark joined the church’s Unity Club, speaking to its members frequently and raising substantial support for the Colored Orphan Asylum, a charity his father and other family members helped found in 1845 and which he served as treasurer or secretary for more than twenty years. In 1882 Clark introduced the noted abolitionist Wendell Phillips when Phillips, under the auspices of the Unity Club, spoke to an audience of 3,000 people.

Clark concentrated his postbellum political efforts on securing national legislation to enforce the rights guaranteed black citizens by the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. He was the most prominent black Republican speaker in the Ohio Valley during the presidential campaigns of 1868 and 1872. The Republicans, who promised a national civil rights law and more federal jobs for black workers, won both times with nearly 100% of the black vote. They failed to deliver on either promise, however. In 1873 Clark organized a meeting in Chillicothe of Ohio’s black leaders. They issued a statement asking black voters to vote for candidates, irrespective of party, who would respond to their needs. Although Clark remained a Republican, he insisted that black voters make the two major parties compete for their votes. After he supported the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876 he joined the Workingmen’s (Socialist) Party, and ran respectably for Ohio Commissioner of Education on its ticket an 1877. He was welcomed back by the Republicans in 1879 and supported James Garfield for President the next year.

In 1882 Clark joined the Democratic Party and supported his friend and fellow parishioner George Hoadly’s 1883 campaign for governor on the Democratic ticket. Hoadly promised to repeal Ohio’s remaining racially oppressive Black Laws and to appoint African-Americans to posts of responsibility. Clark was credited by both parties with swinging enough black votes to the Democrats to ensure Hoadly’s victory over Republican Joseph Foraker. Hoadly kept his promises. He secured the repeal of most of the Black Laws early in his term and he appointed prominent black citizens to a number of positions, including Clark as the first black trustee of Ohio State University. The major unresolved issue was a proposal for mixed race schools.

Ohio’s colored and white schools had been placed under all-white boards in 1874 as a prelude to enacting a mixed race schools law. Hoadly introduced such a law in 1884. Clark was in favor of it provided the teachers, as well as the students, were of both races. But white parents were not willing to have their children taught by black teachers. Clark accurately predicted that black children were not ready to compete with white children without the support of black teachers and that the black students would be victimized. Thus he fought against passage of the law, although most black voters were for it. The law failed to pass that year or in 1885. In the gubernatorial race that fall, Republican Joseph Foraker, who had learned from his previous defeat, promised to pass the mixed race school law, to appoint more African Americans to state jobs, and to give needed financial aid to the AME-affiliated Wilberforce University. Foraker ensured that three black politicians were nominated for the state assembly on the Republican ticket. After winning handily with a huge majority of the black votes, Foraker kept all of his promises. Clark’s policy of having the parties compete for black votes had been proven correct.

In the 1886 Cincinnati municipal elections the Republicans recaptured control of the Board of Education. Clark was soon fired from his job. Gaines High was closed in 1889. No one doubted—least of all Clark—that this was punishment for his apostasy, and a warning to black political aspirants that the right to wield power was reserved exclusively for white citizens. Neither of his two churches supported him, or even took notice when he left town.

Ten years after Clark left Cincinnati, his dire prediction about the mixed race school system was borne out. In 1897 more than 700 black parents signed a petition condemning the school board, the superintendent, the principals, and the teachers for the indignities and insults to which their children were subjected in the mixed schools. Further, in 1908 it was revealed that only 89 black children had graduated from the two Cincinnati High Schools in the 20 years since mixed schools were initiated, although the population of school age blacks children had doubled in that interval.

Clark served as principal of the State Normal School in Huntsville, Alabama for one year. He then moved to St. Louis, Missouri where he was a greatly beloved teacher in the segregated Sumner High School until he retired in 1908.

Clark remained unchurched from the time he left Cincinnati until his death. His will specified that no religious rites be performed at his funeral and that Unitarian layman William Cullen Bryant’s poem, “Thanatopsis,” be read. His Unitarianism was shared by one other member of his family, his younger daughter Consuelo, a graduate of Boston University Medical School, who practiced in Youngstown, Ohio and was an early and active member of the Youngstown Unitarian Church.

Governor Hoadly gave what could have been Clark’s epitaph in an 1885 letter to President Grover Cleveland: “His color has kept him in the shadows; had he been a white man, there is no position in the state to which he might not have aspired.”

There is information on Clark in the published records of both the Colored School Board and the Cincinnati Board of Education, and in the minutes of Cincinnati Board of Education meetings. There are scores of articles about Clark, and speeches and letters by him, in the Cincinnati, national, and abolitionist newspapers. Only a tiny fraction of the hundreds—or more probably thousands—of letters written by and sent to Clark have been located. His personal papers have never been found, and relatively few letters from him have been collected. While there are gaps in The Records of First Unitarian Church of Cincinnati, in the Cincinnati Historical Society Library, this collection does provide much useful data about Clark’s activity in the congregation.

Although out of date, the best-referenced survey of Clark’s life and career remains Lawrence Grossman, “In His Veins Coursed No Bootlicking Blood: The Career of Peter H. Clark”, Ohio History (Spring 1977). Other short biographies, written by those who knew Clark, are T. Thomas Fortune, “Peter Humphries Clark of Ohio”, The New York Freeman (January 3, 1885) and Rev. William Simmons, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising (1887, rep. 1968). There is an entry on Clark in American National Biography (1999). See also Phillip S. Foner, “Peter H. Clark: Pioneer Black Socialist”, in The Journal of Ethnic Studies, Vol.5, No.3; Isaac M. Martin, History of the Schools of Cincinnati (1900); David A. Gerber, Black Ohio and the Color Line 1860-1915 (1976); E. S. Lutton, First Unitarian Church of Cincinnati: Sesquicentennial History (1982); and Charles W. Wendte, The Wider Fellowship (1927).

Article by Walter Herz

Posted January 6, 2006