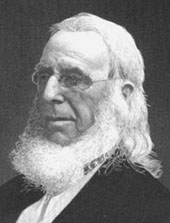

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791-April 4, 1883), Unitarian inventor, entrepreneur, and college founder, was a real-life “rags to riches” hero whose love for humanity and deep religious convictions led him to establish the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, the first postsecondary institution in the United States to provide free education to the poor and to adults, including women.

Peter Cooper (February 12, 1791-April 4, 1883), Unitarian inventor, entrepreneur, and college founder, was a real-life “rags to riches” hero whose love for humanity and deep religious convictions led him to establish the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, the first postsecondary institution in the United States to provide free education to the poor and to adults, including women.

Peter was born in New York City to Methodists Margaret Campbell and John Cooper. Their home was opened to traveling clergy. Peter later recalled that his “father’s religion was of that kind that he feared everybody would go tumbling into hell.” Although he abandoned his father’s doctrine, he never strayed from the work ethic his father instilled in him from an early age.

John Cooper attempted several craft and merchandising occupations, with little success. Among other tasks, Peter had to “boil the hair out of the rabbit skins to be used in the manufacture of hats.” This experience may well have inspired his later invention of gelatin, made by boiling animal skin and connective tissue. He began inventing early in adolescence. He devised a machine for washing clothes, which aided his mother greatly. He helped his family by finding new ways to net wild pigeons, construct shoes, make bricks, and brew beer. So occupied, he had little opportunity for schooling. “My only recollection of being at school,” Cooper explained in his autobiography, “was at Peekskill [New York] about some three or four quarters and a part of the time it was half-day school.” As he began to hone his entrepreneurial skills, his lively curiosity nevertheless helped him to acquire an informal education.

In 1808 Cooper was apprenticed to a New York coachmaker. Although he showed promise in this trade, he declined to take the loan necessary to set himself up in the business. Instead he took a job in Hempstead, Long Island with a manufacturer of cloth-shearing machines. There he obtained a license to make and sell the machines in New York. He then designed, patented, and manufactured an improved version of the machine. He recalled that “the first money I received for the sale of my machines was from Mr. [Matthew] Vassar, of Poughkeepsie, who afterwards founded that noble institution for female education, called Vassar College.”

In 1813 Cooper married Sarah Raynor Bedell. Only two of their six children, Edward and Sarah Amelia, survived childhood. For a time he operated a grocery store in partnership with his brother-in-law. A jack-of-all-trades, he also ran factories to make furniture, glue, and isinglass. In 1828 he founded the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore, Maryland. This made his fortune. He set up other foundries in New Jersey and Pennsylvania and a rolling mill in New York (which he later moved to Trenton, New Jersey).

In addition to the washing machine, Cooper invented a cutting device for lawn mowers, a torpedo boat, and the first American steam locomotive (named “Tom Thumb”). With his brother Thomas, in 1854 he manufactured the first iron structural beams. He also invented the first blast furnace, a compressed air engine for ferry boats, a water-powered device to move barges down the newly-constructed Erie Canal, a machine to grind and polish plate glass, and a musical cradle.

Cooper was the founding president of the New York, Newfoundland & London Telegraph Company, 1854, and of the North American Telegraph Company, 1857. He oversaw the project, directed by Cyrus Field, which in 1866 laid the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

A compulsive builder of social institutions, in 1851 Cooper helped found the Demilt Dispensary. He was one of the incorporators of the New York Juvenile Asylum, 1851. He was as a founding board member of the New York Gallery of Fine Arts, 1844, and the New York Citizens’ Association, 1863.

Cooper’s pursuits were deeply influenced by his Unitarian beliefs, which emerged when he heard Orville Dewey preach at Second Church (now The Community Church of New York) in 1838. He immediately joined Second Church and stayed there until 1855, when he joined the First Congregational Church in the City of New York (now the Unitarian Church of All Souls). He worked closely with the minister, Henry Whitney Bellows, on the United States Sanitary Commission and to promote New York educational reform. While serving as the Assistant Alderman for the New York Common Council, he led the Croton project to improve the city’s water supply by damming the Croton River in Westchester County, New York. When the Common Council merged with the education board, he served as a trustee for over twenty years and led the campaign of the Free Schools Society, organized to give free instruction to New York’s children. He opposed public subsidization of Roman Catholic schooling, saying that no public funds should be used for schools promulgating a religious doctrine.

“Longing to find something that would satisfy the cravings of a rational and moral mind,” Cooper absorbed the teachings of William Ellery Channing, who opposed revelation and original sin, and Elias Hicks, a Foxite Quaker. In his own writing he expressed his Universalist, as well as Unitarian, beliefs. He professed a “God of love-love in action” where all flesh shall see the salvation provided by God. Like many Unitarians he believed that a great union of all Christian sects would share in Jesus as a “great and noble teacher of humanity.”

Unitarianism provided Cooper with a language through which to explore a “rational conception of a Supreme Being.” This led Cooper to couple science and theology. He considered knowledge as “the rule or law of God.” He asked himself what he would do if he, as an inventor, had the power to move matter. He thought that he would “move matter to accomplish the greatest and best thing possible to the imagination . . . [and therefore] would organize, individualize, and immortalize all intelligent minds that have lived or can live.”

Cooper’s religious beliefs also informed his understanding of wealth, which was revolutionary in his time. He wrote, “The production of wealth is not the work of any one man, and the acquisition of great fortunes is not possible without the co-operation of multitudes of men.” He believed it to be the responsibility of the wealthy to exercise Christian charity because “a good human intelligence,” he explained, “feels bound to use all its powers to accomplish the greatest good [for] the greatest number.” This may have been his intention when he founded The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

The cornerstone was laid in 1854 and in 1859 the Cooper Union was chartered with a mission unlike that of any institution of its time. It was founded on the belief that education should be, as Cooper expressed it, “free as water and air.” As a result, it has remained tuition-free to this day, and has allowed working-class people access to what had formerly been reserved for the elite. In its founding deed Cooper articulated the vision of training men and women in practical and vocational arts so they could “earn their daily bread.” He modeled the Union upon several polytechnic schools in Paris, the Birkbeck Institute in London, and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. The Cooper Union offered its first course at night, to students ages sixteen to fifty-nine. The free Reading Room and Library was kept open until ten at night, admitting both women and men.

The Cooper Union also provided free public lectures and was home to the offices of many celebrated Unitarians and Universalists, including Susan B. Anthony, Clara Barton, and Elizabeth Blackwell. After Cooper’s death, Mary White Ovington and John Hayes Holmes worked from Cooper Union to organize the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). William Cullen Bryant and Horace Greeley spoke in the great hall. It was the setting for a celebrated 1860 speech by presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln. In 1876 Cooper, as candidate for the Greenback party, ran for president of the United States, but received less than one percent of the vote.

The Cooper Union was not the only institution of higher education Cooper subsidized. At 87 he traveled south to help fund the Cooper-Limestone Institute. (This was eventually governed by the Spartanburg Baptist Association. Fifteen years after his death, renamed Limestone College, it broke all ties with his heirs.) After receiving generous support from the National Conference of Unitarian Churches for the founding of Antioch College, Horace Mann nominated Cooper as a trustee. Although he did not accept because preoccupied with the Cooper Union, he did provide funding. He spoke at the opening of Vassar Female College in 1865.

Cooper did not escape criticism. Some deemed his vision for Cooper Union “amorphous, preposterous, and impractical.” A few thought him a “snake in the grass” for using shops on the ground floor of Cooper Union as a way to skirt taxes. Cooper charmed his critics with the vision of a truly tuition-free institution, and some of them eventually became donors. Others remained convinced that his inventive and creative mind was hampered by uncritical idealism and stubbornness.

Following Cooper’s death, twelve thousand citizens passed by his coffin at All Souls Church. Robert Collyer, a Unitarian minister, gave the funeral address to a full house, while thousands more flooded the streets. Flags were lowered to half-mast and bells rang as Cooper’s coffin was escorted to Brooklyn. The New York Herald recorded that no funeral in the memory of any living person could compare. One of the most beloved citizens of New York City in his time, Cooper inspired the charitable acts and civic responsibility of other tycoons such as Andrew Carnegie, George Peabody, Matthew Vassar, and Ezra Cornell.

Primary documents pertaining to Cooper are found in the Archives at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Arts and Sciences. Peter Cooper’s Letter to the Trustees [of Cooper Union] (1859, published 1956), Thoughts Presented to the Pupils of the Cooper Union (1859), Mr. Peter Cooper’s Address (1860), Letter of Peter Cooper on Slave Emancipation (1863), Letter from Peter Cooper to the Delegates of the Evangelical Alliance (1873), Letter to the Episcopal Church Congress, with an Address to the Delegates of the Evangelical Alliance (1874), The Science of Religion as Explained by Peter Cooper to the Bishop (1874), “Peter Cooper’s Religious Views: As Expressed in a Speech Delivered at the Ninety-First Anniversary of the Forsyth Street Methodist Church. Christianity the Science of a True Life – Charity the Greatest of All Virtues,” National Journal (March 26, 1881), A Sketch of the Early Days and Business Life of Peter Cooper: an Autobiography (1887). A secretary assisted Cooper in his political, poetic, and theological writings. The Autobiography of Peter Cooper (1882), dictated by Cooper and transcribed from the original shorthand notes, is not often referenced in other works. John Celivergos Zachos, A Sketch of the Life and Opinions of Mr. Peter Cooper (1876), a collection of original sources composed by Peter Cooper, was put together to support Cooper’s presidential nomination. Charles Sumner Spalding, Peter Cooper: A Critical Bibliography of His Life and Works (1941) contains an annotated list of Cooper’s letters and works.

Additional publications, and several photographs of Peter Cooper, can be found in the archives of All Souls Church, New York City. Edward C. Mack, Peter Cooper, Citizen of New York (1949) is the most comprehensive and thorough biography. Other biographies include Allan Nevins, Selected Writings of Abram S. Hewitt: With Some Account of Peter Cooper (1935) and P. Lyon, “Peter Cooper, the Honest Man,” American Heritage (February 1959). See also Orville and M. E. Dewey, Autobiography and Letters of Orville Dewey, D. D. (1883) and R. Q. Topper, “Making Millions and Making a Difference: What We Can Learn from Peter Cooper,” Henry Whitney Bellows Lecture, Historical Society of the All Souls Unitarian Church, New York City (1999).

Article by Nathan C. Walker

Posted November 28, 2005