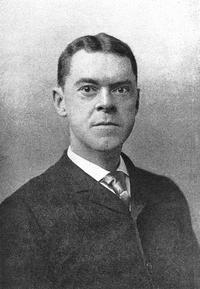

Arthur Foote (March 5, 1853-April 4, 1937), Unitarian church musician and influential music teacher, was a leading member of a group of composers known as the Boston Six or the Second New England School. Together, the Six-John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, George Chadwick, Edward MacDowell, Amy Beach, and Arthur Foote-wrote the first substantial body of indigenous concert hall, or “classical,” music in America. Foote was especially known for chamber music, art songs, and music for choirs. He was considered the “Dean of American Composers” during the first two decades of the twentieth century. He has influenced subsequent generations of musicians through his didactic writings.

Foote’s mother, Mary Wilder Foote, a devout Unitarian, was a friend of the Emersons, Peabodys, Hoars, and Hawthornes. His father, Caleb Foote, was owner and editor of the Salem Gazette. The two had met while teaching Sunday school in Salem’s North Church, then had sung together in meetings of local Unitarian church choirs. Arthur had two older siblings, Henry Wilder Foote, Unitarian minister at King’s Chapel, and Mary Wilder Foote Tileston, editor of inspirational anthologies. After their mother died when he was four, Arthur was raised by his sister, then a teenager.

Henry Wilder Foote married Frances Anne Eliot, daughter of Boston mayor Samuel Atkins Eliot and sister of Charles W. Eliot, president of Harvard. The couple compiled a hymnal for King’s Chapel. Their son,Henry Foote II, and grandson,Arthur Foote II, both Unitarian ministers, continued the family tradition of creative work on new hymnals.

At Harvard, Arthur Foote studied composition and music history under John Knowles Paine. In 1875, a year after graduation, Foote earned the first master’s degree in music ever granted by an American university. Until this time Foote had considered music a hobby, thinking that he would probably join his father on the Salem Gazette. His post-graduate studies with organist B. J. Lang, however, oriented him toward his life’s work in music.

Foote largely supported himself by taking students in piano and organ. In 1876 he began to appear as a piano recitalist, often as a participant in chamber music ensembles. He began working as a church organist in 1876 at the Church of the Disciples in Boston, a “free church” founded by the prominent Unitarian minister, James Freeman Clarke. Foote found that he enjoyed playing in church more than in the concert hall. Two years later he was engaged as organist and choirmaster by First Church, Unitarian, in Boston, a post he held for thirty-two years. “The service of the church was practically the modified one of King’s Chapel,” Foote later wrote. “But by degrees one minister after another made amputations and changes in it, so that finally the Te Deum, etc., was dropped, and the present form came to be used.” He noted with pleasure that, in 1925, the responses he wrote for the church in 1905 were still in regular use.

Foote wrote many anthems and a number of organ pieces for church services. These pieces were intentionally short, highly accessible to the congregation hearing them, and easy for the choir and musicians. He thought it odd that the most popular of his anthems, “Still, Still with Thee,” was one of his most difficult. He wrote secular vocal quartets and choral pieces as well. Among the most ambitious of the latter were three cantatas for choir and orchestra using as texts poems by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—The Farewell of Hiawatha, The Wreck of the Hesperus, and The Skeleton in Armor. Foote also wrote more than a hundred art songs. Although some of his early efforts, like “An Irish Folk-Song,” were popular and often published, he preferred his later songs, such as the settings of First World War poetry which he made in 1919.

The music for which Foote is best remembered today is exclusively instrumental. Almost all of his chamber ensemble compositions have been recorded. In his own time the Four Character Pieces after the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was his most popular orchestral work. His works most often programmed by orchestras since that time are the Night Piece for Flute and Strings and the Suite in E major. The Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Serge Koussevitsky once teased Foote that his Suite in E major, written in 1908 in a style meant to evoke the Baroque era of Bach and Handel, two hundred years before, actually contained a foretaste of jazz rhythm. The composer was astounded.

In the wake of a later generation of American composers-including Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, William Schuman, and Virgil Thomson-who developed a musical idiom recognizably American, the music of Foote and his contemporaries sounds derivative of 19th-century European styles. Actually Foote had a subtle lyrical style all his own. It can be discerned upon listening to a large body of his work. In listening to his violin sonata one is reminded of Brahms, not surprising in that Foote and all the Boston Six, at least in their formative years, were contemporary with Brahms. Foote wrote his violin sonata in 1889, the same year Brahms published his third composition in that form. Into his first piano trio, from 1884, Foote introduced a suggestion of American hymnody.

Three decades later, in a piece for flute, cello and harp called At Dusk, Foote demonstrated that he had adapted his style to include the harmonic innovations of the impressionist French composer Claude Debussy. Foote’s Night Piece, also a late composition, has an exotic charm and freshness which has kept it in the American classical repertoire. His second piano trio and a number of his other mature works have this same quality and deserve to be better known.

Although he later found himself a musical conservative, in his early days Foote was considered a radical for promoting performances of Brahms and Wagner, whom the musical establishment considered too advanced. He later wrote that “These were the days when St. Saëns’ music came to us as a stunning novelty . . . when the new Grieg concerto fascinated every one, and when some of us went over to Bayreuth in 1876 to the first performances of the ‘Niebelungen Ring.'”

Foote adored his older brother in the ministry, Henry Wilder Foote, and, like him was a Unitarian Christian. He helped edit his brother’s Hymns of the Church Universal in 1890, and collaborated with his sister, Mary, in Hymns for Church and Home, prepared for the American Unitarian Association in 1896. Foote, like his mother before him, valued religious tolerance. He rejected contemporary expressions of ethnic pride, nativism, and anti-Semitism. Although he made no explicit verbal statement of his religious opinions, he expressed what lay deepest within himself in music. He wrote that “the object of the artist should be to tell us in music . . . the truths of life and the beauty and sublimity of life.”

Foote and Kate Grant Knowlton were married in 1880. Their one daughter, Katharine Foote Raffy, was responsible for talking her father into writing his autobiography late in life. Foote died in Boston and is buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery.

There is an Arthur Foote Collection at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. There are personal scrapbooks at the Boston Public Library and at the Widener Library at Harvard University. Family papers are in the Harvard archives and at the library of the Essex Institute in Salem, Massachusetts. Music manuscripts can be found at the New England Conservatory of Music Library, the Harvard Musical Association Library, the Boston Public Library, the Library of Congress, and the archives of the Arthur P. Schmidt Company of Boston. Most of Foote’s music was first published by Arthur P. Schmidt.

The Night Piece for Flute and Strings is the most frequently recorded of Foote’s works, often performed in its alternative chamber form, Nocturne and Scherzo for flute and string quartet. Other works that are, or have been available as recordings are the Suite in E major, the Symphonic Prologue Francesca da Rimini, the three string quartets, the two piano trios, the piano quartet, the piano quintet, the violin sonata, the cello sonata, short pieces for violin and piano, chamber works with flute, Five Poems after Omar Khayyam for piano, two songs, and a number of short organ works.

One of the most important of Foote’s pedagogical publications is Modern Harmony in Its Theory and Practice (1905), written with Walter R. Spalding. It was republished as Harmony (1969). He also wrote Some Practical Things in Piano-Playing (1909) and Modulation and Related Harmonic Questions (1919). He contributed many articles to music journals, including “Then and Now, Thirty Years of Musical Advance in America” in Etude (1913) and “A Bostonian Remembers” in Musical Quarterly (1937).

The only full-length biography is Nicholas E. Tawa, Arthur Foote: A Musician in the Frame of Time and Place (1997). Tawa also wrote “Why American Art Music First Arrived in New England,” in Michael Saffle, ed., Music and Culture in America, 1861-1918 (1998), which places Foote in the context of the Second New England School. Foote’s An Autobiography was published posthumously in 1946. It was reissued in 1979 with an introduction and notes by Wilma Reid Cipolla. Cipolla also wrote A Catalog of the Works of Arthur Foote (1980) and the Foote entry in American National Biography. John Tasker Howard, Our American Music (1929, revised ed. 1954) contains a short biography and an appreciation of Foote from the point of view of the early 20th century. Other short biographical essays can be found in the compact disc booklets of recordings devoted to him and in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

Article by Peter Hughes

Posted September 26, 2000