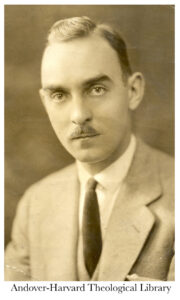

Stephen Fritchman (May 12, 1902-May 30, 1981) was a Unitarian minister. During the 1940s, he was Director of Youth Work and editor of The Christian Register for the American Unitarian Association (AUA). After being ousted as editor in 1947 in a dispute over editorial supervision of the Register (The Fritchman Affair), he returned to the pulpit as minister at the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles.

He was born in Cleveland, Ohio to Addison and Esther Eliza (Hole) Fritchman. His father was of Pennsylvania German stock while his mother came from an English Quaker background. His mother, at age 27, died the day after he was born. Upon completion of high school, he read gas meters in the slums of Cleveland. This experience introduced him to the wretched lives of the underclass and made him the lifelong radical he became.

He was born in Cleveland, Ohio to Addison and Esther Eliza (Hole) Fritchman. His father was of Pennsylvania German stock while his mother came from an English Quaker background. His mother, at age 27, died the day after he was born. Upon completion of high school, he read gas meters in the slums of Cleveland. This experience introduced him to the wretched lives of the underclass and made him the lifelong radical he became.

He studied for a year at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Finance and then transferred to Ohio Weslayan University in 1922 to study for the Methodist ministry. After receiving his B.A. from Ohio Weslayan in 1924, he stayed on for a year as a graduate assistant in the English Bible Department.

Fritchman moved to New York City after this. Here he attended Union Theological School where he received the B.D. in 1927, and New York University, where he received an M.A. in 1929. His graduate thesis was titled “The Inner Light in the Society of Friends.” During this time he supported himself by teaching English at Washington Square College and by working as a religious news editor for the New York Herald Tribune.

In 1928 he moved to Boston, Massachusetts to teach English literature at Boston University. That fall he married Frances Putnam, a Unitarian. He was ordained a Methodist minister in 1929, but soon applied for Unitarian fellowship.

He was called by the Petersham, Massachusetts Unitarian Church in 1930. During his Petersham ministry he continued his studies at Harvard Graduate School. Two years later he moved to Bangor, Maine where he served for six years. He became more outspoken in Bangor, and members of the congregation began to criticize him for his pacifism, his opposition to compulsory high school ROTC, and his support for the New Deal. Fritchman and his wife Frances found that they enjoyed working with the youth of the church, who were more open minded. They never had children of their own. Years later Fritchman recalled that in 1936, “The Spanish Civil War did more to destroy my Christian presuppositions than any other single event in my life.”

In 1938 he was hired as Director of Youth Work by the American Unitarian Association (AUA) to coordinate activities and programs for high school and college age youth. The Fritchmans moved back to Boston, Massachusetts, where he was an energetic and eloquent leader and administrator.

Fritchman encountered opposition to his political leanings in 1940 when Lawrence Davidow, an AUA Board member from Detroit, complained that the American Youth Congress (AYC), with which the Young Peoples Religious Union (YPRU) was affiliated, was a communist front. The Unitarian YPRU, under Fritchman, was one of the few groups that hadn’t withdrawn from the AYC when it came out in support of the 1939 German-Soviet nonaggression pact. Three board members including Davidow, who had been chief legal counsel for the United Automobile Workers and was a former Socialist, investigated the AYC. As a result of their investigation, the YPRU severed its ties with the American Youth Congress.

In 1941, with Fritchman’s support and advice, the YPRU reorganized itself as an independent, democratic, youth-run organization, now called American Unitarian Youth (AUY). Fritchman hired Martha Fletcher as Associate Director of Youth Work to help him work with the independent AUY.

In 1942, AUA President Frederick Eliot appointed Fritchman to serve as editor of The Christian Register in addition to performing his youth duties. The Register had been an independent bi-weekly magazine. When it ran out of money in 1940, the AUA board voted to assume the magazine’s liabilities, subsidize publication, and make The Christian Register an official house organ. Subscriptions increased but the deficits continued. Fritchman switched it to a monthly publication and raised the magazine’s profile. The theme of his first issue was race relations. It included an article by Ethelred Brown, the sole black Unitarian minister at the time. Fritchman built the Register into a lively, profitable and provocative magazine.

In addition to holding two positions with the AUA, Fritchman found time to work with a variety of progressive organizations, write two books and edit two more. He often spoke at meetings of Popular Front groups including the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC), Russian War Relief, National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, Jefferson School of Social Science, and American Youth for Democracy. Such groups were more prone to promote Stalinist interests and propaganda than many recognized at the time or since. Since The Christian Register didn’t pay its authors, Fritchman solicited articles from many of the speakers he met at political meetings. These included; Edgar Snow, Archibald MacLeish, I. F. Stone, W. E. B. DuBois, and Paul Robeson. Under Fritchman, The Christian Register grew in subscriptions and influence.

The books he wrote during his years at AUA headquarters were: Young People in the Liberal Church (1941), and Men of Liberty: Ten Unitarian Pioneers (1944). He also edited Prayers of the Free Spirit (1945), and Together We Advance (1946).

Starting in the early 1940s, Herbert Philbrick, an FBI undercover agent, kept track of suspected communists and their associates in the Boston area. Since Fritchman’s name appeared on Popular Front letterheads and mass meeting announcements, he was soon a subject of interest. The FBI also noted articles that Fritchman wrote that were published in The New Masses and The Daily Worker.

On May 14, 1946, Frank B. Frederick, a lawyer and a new AUA board member, reported to AUA President Frederick Eliot that Linscott Tyler, a Unitarian layman in Hingham, Massachusetts and former FBI agent, had told him that Fritchman was a member of the Communist Party. Tyler had further reported that the FBI had been tracking Fritchman’s activities, filming his meetings, and monitoring his telephone conversations. Over the next three months, the AUA executive committee held five hearings on the matter. They heard testimony from the complainants, Lawrence Davidow of Detroit, Donald Harrington the minister at the Community Church of New York, and Linscott Tyler. They also heard persons invited by Fritchman: Edwin B. Goodell, chair of the editorial board of The Christian Register; Ernest Kuebler, director of the AUA Division of Education; and members of the AUA Youth Work Committee.

That summer, heated discussion went on late into the night at the Midwest Lake Geneva Summer Assembly on the issue of whether liberals could work cooperatively with Communists. AUY was holding its continental convention concurrently with the annual summer meeting of the Western Unitarian Conference. One question was whether the AUY should affiliate with the World Federation of DemocraticYouth (WFDY). Homer Jack, a recent graduate of Meadville Lombard Theological School, brought in youth leaders from a nearby conference to support his claim that the WFDY was a communist front. In September, details of the AUA hearings leaked to the press, and the “Fritchman Controversy” became national news.

That fall, the AUA board’s executive committee agreed by a slim margin to retain Fritchman as youth director, and by a wider margin to retain him as Register editor. At the October 9, 1946 meeting of the full AUA board, Fritchman was exonerated by a vote of twenty-nine to two on the charge that he was “proselytizing on behalf of the Communist Party.” A vote to retain him as Director of Youth Work was twenty-four in favor and seven opposed. A few days after this, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) issued Fritchman a subpoena to appear at a hearing, along with representatives of the Unitarian Service Committee. He appeared on October 23, 1946 but provided scant testimony.

Fritchman submitted his resignation as AUY Executive Director effective February 15, 1947, but he stayed on as editor of the Register. Conservative Unitarians who opposed Fritchman and any idea of a connection between religion and social issues formed The National Committee of Free Unitarians. Liberal Unitarians on the other hand, headed by James Luther Adams, responded with a declaration of support for Unitarian freedom and diversity in religious outlook. They supported the application of religious and ethical insight to the practical issues of common life, as opposed to”pure spirituality.”

President Eliot wanted to retain Fritchman as editor of The Christian Register. On December 11, 1946, he announced the creation of a Register editorial advisory panel to “help Steve.” The following May, Fritchman declared he could not work under the new arrangements, which included making proof sheets of the Register available in advance to Eliot. He announced his resignation. Eliot asked him to put it in writing. Fritchman changed his mind, announcing he would bring the matter before the 1947 AUA annual meeting in mid-May. The executive committee suspended him immediately and the full board confirmed his termination. Two days later, after a full day of debate, delegates at the AUA annual meeting defeated a resolution requesting the board to reconsider its decision. The New York Times carried a front page story with the headline, “Unitarians Suspend Fritchman, Once Called a Pro-Red, as Editor.”

Stephen Fritchman was called to the First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles, starting in January 1948. Early on, he proposed to the church trustees that the church bylaws and publicity state that the church welcomed men and women of all races and national origins. Some members left. In Los Angeles, he continued with the radical activities and associations that had brought him under fire in the east. Times, however, had changed radically, with the near-collapse of the U.S. Communist Party and the end of its Stalinist control. Radicals became free to deal with social problems and human needs directly without adherence to Party line. From the pulpit, on occasion, Fritchman denounced Soviet imperialism as strongly as he had been criticizing its American counterpart. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was active in Hollywood, and Fritchman waded into the fray. He was summoned to appear and testify. His staunch defense of civil liberties and freedom of speech led to new relationships for him with liberals and leftists in California, including the motion picture artists labeled the “Hollywood Ten.” Continuing to support immigrant rights, he was active in the American Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born.

Under Fritchman’s ministry, the Los Angeles church grew in membership to 1,250, with weekly attendance at 443, and the church school at 327. The church youth group had 45 members. Up to 1,000 would gather for church forums on social and religious issues. His preaching covered the full range of topics for the time: religion, the Bible, Vatican II, capital punishment, violence, civil disobedience, the Middle East, mixed marriages, the human rights of women, etc. The congregation operated a little theatre, a writer’s group, a woman’s group, and a senior citizens’ community group. An arts festival flourished, which eventually sponsored appearances by Arthur Miller, Pete Seeger, and Paul Robeson. It hosted one of the first exhibits of work done exclusively by black artists.

In 1952 Fritchman was invited to Melbourne, Australia to address the 100th anniversary of the Melbourne Unitarian Church. When the U. S. State Department denied his request for a passport, he was forced to cancel the trip.

For ten years he hosted a weekly radio program on a succesion of radio stations, drawing ever larger audiences until the radio station took him off the air in response to complaints from advertisers that he ws too controversial. He worked his way up to the CBS network station in Los Angeles, KXNT. When he offended CBS management, his radio series ended.

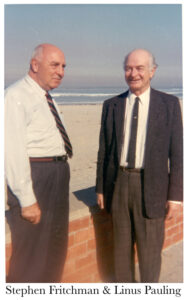

Television provided fresh opportunities. Fritchman appeared as a critic of life in the United States on the English television program We Dissent, and he was interviewed for a 90-minute CBS network special about American funeral practices based on Jessica Mitford’s book, The American Way of Death. Mitford spoke at the church as did Margaret Mead, W.E.B. DuBois, Edgar Snow, Steve Allen, Charles Collingwood, Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, Ashley Montagu, Corliss Lamont, Albert Kahn, Robert Hutchins, Harold Urey, Bishop James Pike, Karl Menninger and Linus Pauling. Early in Fritchman’s ministry, Pauling and his wife Ava became church members and family friends. They shared a passionate concern about world peace, often marching together in peace protests accompanied by many additional Unitarians.

In 1954, the California legislature passed the Levering Act requiring a signed loyalty oath for all people and organizations claiming local or state tax-exempt status. The Los Angeles Unitarian church, led by Fritchman, the Unitarian church of Berkeley, the Unitarian Universalist church of San Jose, the Methodist church of San Lendro, and others, contested the law. Refusing to sign any loyalty declarations, the churches paid taxes while contesting the legality of the California law. In 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Levering Act violated the First Amendment of the Constitution and instructed the California government to refund, with interest, all taxes paid by the churches.

In 1954, the California legislature passed the Levering Act requiring a signed loyalty oath for all people and organizations claiming local or state tax-exempt status. The Los Angeles Unitarian church, led by Fritchman, the Unitarian church of Berkeley, the Unitarian Universalist church of San Jose, the Methodist church of San Lendro, and others, contested the law. Refusing to sign any loyalty declarations, the churches paid taxes while contesting the legality of the California law. In 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Levering Act violated the First Amendment of the Constitution and instructed the California government to refund, with interest, all taxes paid by the churches.

Finally, in 1958, the U.S. government granted Fritchman a passport so he could attend the Tenth Congress of the World Council of Peace in Stockholm the following year. In 1960 he participated in the Japan Conference on Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in Tokyo. In 1963 he attended a Peace Congress in London and went on to international peace meetings in Warsaw. In 1967 he visited the Soviet Union and in 1973 the People’s Republic of China. In China, he placed a pot of bright red poinsettias on the tombstone marking the grave of Anna Louise Strong, a journalist and long-time friend banished from the Soviet Union by Stalin in 1949.

Fritchman opposed the Vietnam War, advocating unilateral American withdrawal. He counseled young men about military service, and encouraged conscientious objection and draft resistance, while respecting the commitment of those who chose military service. He supported the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The choir of the Los Angeles church joined with black choirs from several churches when Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and Fred Shuttlesworth spoke before thousands in Los Angeles on May 26, 1963. The church heard civil rights speakers, and sent money and young members east to join the Freedom Riders and work in voter registration projects. In March 1965, after the slaying of Unitarian minister James Reeb in Selma, Alabama, Fritchman traveled to Selma to attend the memorial service and to participate in the third Selma to Mongomery March. That August, he and his congregation were deeply involved in the aftermath of the six-day-long Watts Riots. Over the following months the congregation worked to respond to the needs of the surrounding community.

The Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) also responded to the riots in cities across America. Homer Jack, director of the UUA Department of Social Responsibility, called an Emergency Conference on the Unitarian Universalist Response to the Black Rebellion in 1967. A group from the Los Angeles First Unitarian Church, Black Unitarians for Radical Reform (BURR), played a key role in articulating the concerns of black Unitarian Universalists at the conference when it met in New York City. The BURR group suggested a blacks-only meeting. Out of that came the Black Unitarian Universalist Caucus (BUUC) which asked the UUA Board of Trustees to create a Black Affairs Council (BAC) with a quarter million dollar annual budget.

In 1963, Fritchman delivered the Berry Street lecture to the Unitarian Universalist Ministers Association. He received an honorary L.H.D. from the Starr King School for the Ministry in 1967. The Unitarian Universalist Association presented Fritchman with the Holmes-Weatherly Award for lifelong commitment to social justice in 1969 and the Award for Distinguished Service to the Cause of Liberal Religion in 1976.

Fritchman was under FBI scrutiny for over 30 years. The government never initiated a legal case against him, and no evidence of illegal activity was ever found. He was asked to testify at hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee held in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles. “I detest name-calling,” he said when called to testify by HUAC. He denied being a communist and he denied having any secret allegiances, saying, “As a liberal American citizen, I serve in many organizations with whose purposes of service to mankind I approve. My religion, ‘love of God and service to man,’ means participation as an individual in many causes assisting our American tradition of democratic advance.”

Fritchman denied he was a Communist. In California, asked by his colleagues if he was a communist, meaning that he believed that communism was pointing the way to a better future for humanity, he readily replied that he did. This was a perfectly acceptable, if questionable, reply in the 1950s after the virtual breakup of the American Communist Party, when communists were free to pursue a variety of strategies. The Fritchman controversy, however, occured in the 1940s, when the U.S. Communist Party controlled most communist activity and was itself under the control of the Soviet Union, and ultimately Joseph Stalin. A close scrutiny of the record for those days indicates the high probability that Stephen Fritchman was a valued insider in the Community Party, whether or not he carried a membership card. What he did is clear. Just what he thought he was doing is not.

Analyses of the contents of The Christian Register by both Leon Milton Birkhead, National Director of Friends of Democracy, and Warren B. Walsh, Professor of Russian Studies, Syracuse University, New York, show a political bias in the Register that favoured Communist, pro-Communist and fellow traveler authors, many of whom were not Unitarians, and excluded other political perspectives almost completely in its articles, book reviews, and letters to the editor. It was Fritchman’s irrepressible drive that the whole magazine, not just the editorial columns, reflect his political perspective that led to his dismissal as editor.

His youth work showed a similar propensity. Martha Fletcher, his associate director, resigned her position in 1945 to take over youth work for the Communist Party. In this capacity she took charge of American Youth for Democracy, a makeover of the Young Communist League, and American Youth for a Free World, created to involve American youth in international communist youth fronts. Fritchman promoted AUY participation in these organizations, with AUYers attending their founding conventions and subsequent events. In 1947, Martha Fletcher was heading a Communist Party cell that met in Boston. Fritchman promoted his cause at youth conferences. He involved the AUY in communist fronts. He himself belonged, by one count, to 24 such fronts and 11 other activities “not calculated to diminish his reputation as a fellow traveler.” High School Week at (Unitarian) Star Island, New Hampshire in June 1946 featured three speakers, Martha Fletcher, Dirk Struik, a self-proclaimed Marxist and member of Fletcher’s cell group, and Herta Tempi, a member of the German Communist Party later removed, by Raymond Bragg, from her post as Director of the Unitarian Service Committee in Paris, France for misuse of her position to promote communist interests.

In 1977, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request, the FBI sent Fritchman 767 pages of photocopies from his FBI files.

He was a warm, friendly person with a sense of humor and a quick wit. He was a dedicated, competent, and effective minister, and a tireless worker for social justice. His writings show a strong, persuasive sense of churchmanship, and a care for the liberal church as a religious institution.

He retired as minister of the Los Angeles church in 1969, and served the Unitarian Church of Palm Springs from 1969 to 1977. He died in Glendale, California.

Ministerial files for Fritchman are in the archives of the Andover Harvard Theological School Library in Cambridge, Massachussetts. They also have files on the “Fritchman Controversy,” The Christian Register, and the Unitarian Service Committee. Two document cases of First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles records are in the Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research. In addition to books mentioned in the text, Fritchman wrote, Unitarianism Today (1950). A bibliography of books, sermons, and addresses is in For the Sake of Clarity: Selected sermons and Addresses of Stephen H. Fritchman, ed. Betty Rottger and John Schaffer (1992). A Collection of documents on the “Fritchman Controversy” are found in Charles W. Eddis, Stephen Fritchman: The American Unitarians and Communism (2011). Fritchman’s book, Heretic: a partisan autobiography (1977) and Philip Zwerling, Rituals of Repression: Anti-Communism and the Liberals, (1985) are also useful sources.

Ralph Lord Roy, Communism and the Churches (1960), and Edward B. Wilcox, The Strange Case of Stephen H. Fritchman (1947), provide contemporary views of Fritchman and the “Fritchman Controversy” while Dan McKanan, Prophetic Encounters: Religion and the American Radical Tradition (2011) offers a useful exploration of the longer term relationship between radicals and religion in America. Extensive reporting about the “Fritchman Controversy” can be found in newspaper archives including over 30 articles in the New York Times. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) records can be searched on the Internet at vault.fbi.gov.

Article by Charles Eddis

Posted June 20, 2012