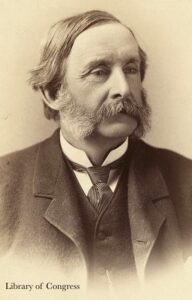

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823-May 9, 1911) was one of the most distinguished and multi-talented Unitarians of the nineteenth-century, yet few people today are aware of his prominence or the extent of his interests and achievements. Minister, author, activist, lecturer, soldier, naturalist, physical fitness enthusiast—he was all of these things and more.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson (December 22, 1823-May 9, 1911) was one of the most distinguished and multi-talented Unitarians of the nineteenth-century, yet few people today are aware of his prominence or the extent of his interests and achievements. Minister, author, activist, lecturer, soldier, naturalist, physical fitness enthusiast—he was all of these things and more.

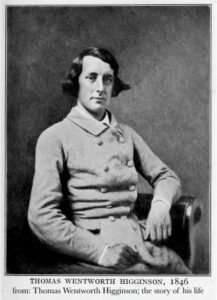

Higginson was born in Cambridge, Massachussetts. His father had been successful in the shipping trade, but was bankrupted by the embargo preceding the War of 1812. He died when Wentworth, as he preferred to be called, was eleven. Raised in an all-female household, he was well-educated and entered Harvard at the age of 13, the youngest of his class. He was an excellent student, but due to his youth and unusual height—well over six feet—he felt ungainly and socially awkward. Upon graduation he was undecided as to a career and for the next year and a half tutored the children of a wealthy cousin.

During his college years and in the period immediately following, Higginson was drawn to the spiritual vision and social activism of the Transcendentalist movement which was in full swing during the 1840s. As a second-generation Transcendentalist he attended his first Emerson lecture at the age of 12, purchased books of the German and British Romantics at Elizabeth Peabody’s Foreign Book Shop in Boston, and was an occasional visitor at Brook Farm in West Roxbury. His closest friends, including Margaret Fuller and William Henry Channing, were key figures in the Transcendentalist circle. Caught up in the enthusiasm of “the period of the Newness,” as the movement was then termed, he wondered in his journal, “whether my radicalisms will be the ruin of me or not.”

As he noted in his memoir, Cheerful Yesterdays, “Under the potent influences of Parker and Clarke I found myself gravitating toward what was then called the ‘liberal’ ministry.” Accordingly, in 1844, he entered the Harvard Divinity School. His graduation speech, “The Clergy and Reform,” set the tone of his ministry. “There are social evils against which we know that Christ if alive would have protested with the whole strength of his soul,” he argued; “and yet those who fill the office of ministers of Christ…have not only left them untouched and even unmentioned but actually have lent their influence by threatening, by slander, and even by satire, against those who would touch them.” His eloquence caught the attention of the Unitarian congregation in Newburyport, who offered him his first settlement in 1847. It also allowed him to wed his cousin, Mary Channing, daughter of Walter Channing, physician and brother of William Ellery Channing.

He was committed to the antislavery cause well before going to Newburyport, having vigorously opposed the US war of aggression against Mexico, which was widely seen as a pretext for the extension of slavery. Settled in Newburyport, he took up local causes as well, including the plight of female factory workers who worked long hours for pitiful wages. He also established an evening school for the adult education of working people. His antislavery views and support of factory workers aroused the ire of leading members of his congregation. When, in a Thanksgiving sermon, Higginson reproached church members for their materialism, their tolerance of slavery and for having helped elect a slave-owner as president, opposition grew, leading to his resignation in 1849.

Forced to seek other means of earning an income, Higginson turned to free-lance writing and lecturing on the Lyceum circuit. And now that he was relieved of ministerial duties, he found time for nature studies and cultivating friendships with Emerson, Thoreau, and others similarly in pursuit of literary careers. He was an enthusiastic admirer of Thoreau’s writing, especially his Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, a book he claimed to reread every year.

He found it difficult to strike a balance between his writing and his social activism. Twice, in 1848 and 1850, he ran for Congress on the Free Soil ticket. He lost, but felt it was worth the effort to advance the antislavery cause. Temperance was another reform that drew his attention. But it was the “woman question” that—along with ending slavery and “colorphobia”—consumed most of his time and energies. He signed the call for the first National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850 and frequently spoke at women’s rights meetings. He advocated equal pay for women, female representation on committees and boards, college education for young women, equality of men and women in marriage, as well as woman suffrage. In 1853 he addressed the topic of “Woman and Her Wishes” before the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. “The protest of women,” he argued, “is not against a special abuse, but against a whole system of injustice; and the peculiar importance of political suffrage to woman is only because it seems to be the most available point to begin with. Once recognize the political equality of the sexes, and all the questions of legal, social, educational and professional equality will soon settle themselves.”

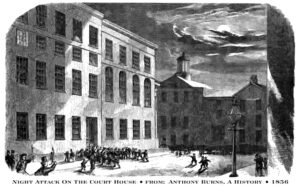

Initially, Higginson declared himself a disunion abolitionist, convinced that the Constitution could never be amended to abolish slavery as long as the slave states remained in the Union. But with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, followed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, he moved toward a more radical position. Citing “the higher law,” he helped establish the Boston Vigilance Committee, vowing to resist the rendition of fugitive slaves. In 1851 he participated in the failed attempt to rescue Thomas Simms from a Boston courthouse. He took an even more active role in the effort to free Anthony Burns in 1854. With a small group of men he stormed the Federal Courthouse, breaking down the door with a battering ram. As he rushed inside, shots rang out and fighting ensued, leaving one of the deputies mortally wounded. He was indicted for his part in the affair, but was never arrested or brought to trial.

Initially, Higginson declared himself a disunion abolitionist, convinced that the Constitution could never be amended to abolish slavery as long as the slave states remained in the Union. But with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, followed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, he moved toward a more radical position. Citing “the higher law,” he helped establish the Boston Vigilance Committee, vowing to resist the rendition of fugitive slaves. In 1851 he participated in the failed attempt to rescue Thomas Simms from a Boston courthouse. He took an even more active role in the effort to free Anthony Burns in 1854. With a small group of men he stormed the Federal Courthouse, breaking down the door with a battering ram. As he rushed inside, shots rang out and fighting ensued, leaving one of the deputies mortally wounded. He was indicted for his part in the affair, but was never arrested or brought to trial.

In 1852 he received a call to serve the the Free Church in Worcester, Massachussetts, a congregation organized along the lines of Theodore Parker’s in Boston. Worcester was a hot-bed of antislavery activity and, unlike Newburyport, the church fully supported Higginson’s involvement. Amidst his reformist activities, he was also becoming a widely-known speaker, lecturing in the East and the Midwest on literature, history and nature, as well as abolition and women’s rights. However, as his own prominence grew, his wife’s health declined. Suffering from crippling rheumatism, they thought wintering in the Azores might offer her some relief. It was a welcome break for Higginson too, leading him to reflect on the limitations of the ministry, the shortcomings of the church and, at the same time, to broaden his views of religion. Unfortunately, the trip did little to improve Mary’s health.

While living in Worcester Higginson joined the school committee, integrating classrooms and raising teacher salaries; led a campaign for building a free public library; formed a local natural history society; and organized a boating club for young men and women. An early proponent of physical culture, he engaged in gymnastics, a variety of sports, and outdoor activities. “Physical health is a necessary condition of all permanent success,” he insisted in “Saints, and their Bodies,” an essay for The Atlantic magazine. “To the American people it has a stupendous importance, because it is the only attribute of power in which they are losing ground.”

With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill in 1854 residents were to determine whether or not slavery would be allowed in the newly formed territories. New Englanders were encouraged to move to Kansas to settle and vote against slavery. These settlers were attacked by “Border Ruffians” from Missouri determined to drive them out. After the sacking of Lawrence by the Missourians in 1856, Higginson, as an agent of the Kansas Aid Committee, purchased guns and ammunition and took these to Kansas in order to arm the settlers. “I enjoy danger,” he wrote in his journal; “while I know that I have incurred the death penalty for treason under U.S. laws and for arming fugitives to Kansas.”

Higginson first met John Brown a year and a half later, and joined with five others, including Theodore Parker and Samuel Howe, to form the “Secret Six” to raise money for Brown and support him in his effort to raise a slave insurrection in the South. Following Brown’s failed raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, Higginson hatched a plot to free him, though Brown preferred a martyr’s death instead. He was the only member of the Secret Six who remained in the country during the trial and subsequent congressional investigation of the Harpers Ferry affair.

By this time, he had resigned from the Free Church, devoting his energies increasingly to writing, abolition, women’s rights and the care of his invalid wife. He became a regular contributor to The Atlantic, with articles on nature, culture, and current affairs, and a series on slave revolts. In an essay, “Ought Women to learn the Alphabet?,” he argued that “woman must be either a subject or an equal; there is no middle ground. Every concession to a supposed principle only involves the necessity of the next concession for which that principle calls. Once yield the alphabet, and we abandon the whole long theory of subjection and coverture.”

By this time, he had resigned from the Free Church, devoting his energies increasingly to writing, abolition, women’s rights and the care of his invalid wife. He became a regular contributor to The Atlantic, with articles on nature, culture, and current affairs, and a series on slave revolts. In an essay, “Ought Women to learn the Alphabet?,” he argued that “woman must be either a subject or an equal; there is no middle ground. Every concession to a supposed principle only involves the necessity of the next concession for which that principle calls. Once yield the alphabet, and we abandon the whole long theory of subjection and coverture.”

In April 1861, he received a reply to another of his articles, “Letter to a Young Contributor.” It consisted of a small packet of poems from an admirer in Amherst, Massachussetts, along with the note, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” These four enigmatic poems written on scraps of paper gave him “the impression of a wholly new and original poetic genius.” He quickly answered this letter from Emily Dickinson, offering a few words of advice and inviting further correspondence. They continued to exchange letters until she died in 1886, but they met only twice. Following her death he assisted in editing her poems for publication, unaware that they had been revised by Mabel Loomis Todd, who had come into possession of them. Higginson has been unjustly criticized for having made the changes himself.

The same month Higginson received the letter from Dickinson, Confederate forces fired on Ft. Sumter. He had been devoting long hours to walking, solitude, and nature study, but by March of the following year he petitioned to raise a regiment of troops. He would have preferred that the South secede, but when the Congress passed an act emancipating all slaves used in rebellion he decided that as “no prominent anti-slavery man has yet taken a marked share in the war,…I have made up my mind to take part in the affair, hoping to aid in settling it the quicker.” In November 1862 he received an offer to command the first black regiment of the Civil War, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, which he readily accepted. (The 54th Massachusetts Infantry, led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, was authorized in March 1863. It was the first black regiment recruited in the North.)

The regiment was recruited, trained, and stationed at Beaufort, South Carolina. Many doubted the bravery and fighting ability of freed slaves, but Higginson had confidence in his troops. The regiment made successful raids along St. Mary’s River and participated in the occupation of Jacksonville. While in camp, Colonel Higginson socialized with his men and took note of the songs they sang, resulting in the first account in print of African-American spirituals. Injured in another upriver raid, Higginson resigned in October 1863, but continued to fight for equal treatment of African-American troops, especially in regard to pay. “Till the blacks were armed, there was no guaranty of their freedom,” he concluded in his account of the experience, Army Life in a Black Regiment. “It was their demeanor under arms that shamed the nation into recognizing them as men.”

The regiment was recruited, trained, and stationed at Beaufort, South Carolina. Many doubted the bravery and fighting ability of freed slaves, but Higginson had confidence in his troops. The regiment made successful raids along St. Mary’s River and participated in the occupation of Jacksonville. While in camp, Colonel Higginson socialized with his men and took note of the songs they sang, resulting in the first account in print of African-American spirituals. Injured in another upriver raid, Higginson resigned in October 1863, but continued to fight for equal treatment of African-American troops, especially in regard to pay. “Till the blacks were armed, there was no guaranty of their freedom,” he concluded in his account of the experience, Army Life in a Black Regiment. “It was their demeanor under arms that shamed the nation into recognizing them as men.”

While he was away, his wife, Mary, moved to Newport, Rhode Island, where she felt she would be better cared for. Wentworth joined her there after he was discharged. He resumed his writing career, publishing articles on his army experience, book reviews, and a translation of the works of Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Asked to serve on the Newport School Committee, he succeeded in integrating the public schools and introducing a physical fitness program. He also mentored Helen Hunt and Julia Ward Howe, two women prominent in Newport literary circles.

Following the assassination of Lincoln, Higginson denounced the treatment of African-Americans under Johnson’s plan of Reconstruction, which, in his view, legitimized the continued oppression of black people in the South. “It is simply that we are forgiving our enemies,” he wrote, “and torturing only our friends.” It was largely for this reason that Higginson supported the Fifteenth Amendment as an exclusively Negro suffrage law, to the dismay of Susan B. Anthony and others who wished to enfranchise both blacks and women. This led to a split in the woman suffrage movement between the National Association, led by Anthony and Stanton, and the American Association, led by Lucy Stone. Committed to the American Association, Higginson served for fourteen years as co-editor and frequent contributor to the Woman’s Journal, an organ of the A.W.S.A. He tried but failed to reconcile the two groups.

Higginson was actively involved in many clubs and organizations. He was a member of Julia Ward Howe’s Town and Country Club and the Radical Club. In 1867, he helped to found the Free Religious Association of which he was a vice-president. As a Transcendentalist Unitarian minister he had stressed the ethical application of religion and embraced an increasingly universal and inclusive definition of faith. His religious cosmopolitanism was reflected in positive assessments of Buddhism and Islam and in a widely circulated essay originally published in The Radical magazine, “The Sympathy of Religions.” “There is a sympathy in religions, and this sympathy is shown alike in their origin, their records, and their career,” he wrote. “Each of these, in short, is Natural Religion plus an individual name. It is by insisting on that plus that each religion stops short of being universal.”

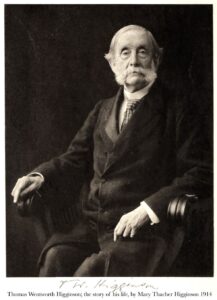

His years in Newport were quite unsatisfactory. He continued to write and lecture, but the care of his invalid wife became increasingly difficult and, aside from his visits to Boston, he felt removed from the thick of things culturally and politically. His financial circumstances, which had always been quite modest, were dramatically improved with the publication of the Young Folks’ History of the United States, by far his most lucrative publishing venture. It was translated into several languages and adopted for use by public schools. Following the death of his wife in 1877, he took his first trip abroad and, upon his return, moved back to Cambridge. In 1879 he married Mary Thacher, who was more than twenty years younger. In 1881 he became a father for the first time, at the age of 57.

The Young Folks’ History was followed, in 1885, with A Larger History of the United States, written for adults. Higginson’s work as a historian and biographer has not been sufficiently appreciated. The Larger History was the first to take account of the substantial role of women in American history. His biography of Margaret Fuller was written to correct the distortions of the Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, edited by Emerson, Channing, and Clarke. His autobiographies, Army Life in a Black Regiment, Cheerful Yesterdays, and Part of a Man’s Life, are detailed accounts of his life and times spanning the greater part of the nineteenth-century. Having outlived many of his contemporaries, he wrote biographical sketches of most of them. In all, he published more than 25 books and hundreds of essays, columns, and reviews.

Though he might have settled at last into a life of letters, Higginson continued to be involved in reform and public affairs. He served in the state House of Representatives, on the state Board of Education, and even did a stint as the governor’s chief of staff. In the course of these engagements he promoted the enfranchisement of women, beneficial treatment of the poor and homeless, and religious freedom. He was outspoken in opposition to anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism. He rejected the notion of a social melting-pot, advocating the goal of cultural pluralism instead. Although his record on organized labor is mixed, he was an advocate of state socialism as a remedy for monopoly capitalism.

Though he might have settled at last into a life of letters, Higginson continued to be involved in reform and public affairs. He served in the state House of Representatives, on the state Board of Education, and even did a stint as the governor’s chief of staff. In the course of these engagements he promoted the enfranchisement of women, beneficial treatment of the poor and homeless, and religious freedom. He was outspoken in opposition to anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism. He rejected the notion of a social melting-pot, advocating the goal of cultural pluralism instead. Although his record on organized labor is mixed, he was an advocate of state socialism as a remedy for monopoly capitalism.

During the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth-century, Higginson decried Negro lynchings and Jim Crow legislation in the South. He led a campaign to rid the Civil Service of corruption. And he joined in the formation of the Anti-Imperialist League hoping to marshal public opinion against U.S. imperialism in the Philippines. As a noted essayist, reformer, historian, literary critic, and public servant he achieved national stature. Among forty candidates in a public poll conducted by the Literary Life magazine, Higginson placed fourth in prominence of living Americans, behind Edison, Twain, and Carnegie.

Although he remained a reformer, he became, in his later years, less radical. The fervent militancy of the antebellum period shaded towards moderation in the decades following the war. But it would be wrong to claim that he ever relented in his quest for justice and human rights. His perennial optimism, reflected in the title of his memoir, Cheerful Yesterdays, placed him, unfairly I believe, in the context of the “genteel tradition” of effete and sentimental writing. He died at the age of 87, active until the end. He was buried out of the Unitarian Church in Cambridge, accompanied by an honor guard of black Army soldiers. He once described himself as a horse that never won a race but “was prized as having gained a second place in more races than any other horse in America.”

Major collections of Higginson’s manuscripts are held at the Houghton Library of Harvard University and the Boston Public Library. Bibliographical material will be found in The Transcendentalists: A Review of Research and Criticism, edited by Joel Myerson. Many of his works are available in digital versions on-line. A selection of his articles and essays will be found in The Magnificent Activist: The Writings of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, edited by Howard N. Meyer (2000). Valuable autobiographical resources include Out-door Papers (1863); Army Life in a Black Regiment (1870); Cheerful Yesterdays (1898); Part of a Man’s Life (1905), and Letters and Journals of Thomas Wentworth Higginson 1846-1906, edited by Mary Thacher Higginson (1921). His article “Negro Spirituals” in The Atlantic Monthly (June 1867) ia available online at theatlantic.com. For more information see William Francis Allen, Slave Songs of the United States (1867). As Massachusetts State Military Historian, Higginson compiled the two volume Massachusetts in the Army and Navy During the War of 1861-65 (1896).

Major biographies include Thomas Wentworth Higginson: The Story of His Life, by Mary Thacher Higginson (1914), Dear Preceptor: The Life and Times of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, by Anna Mary Wells (1963), Colonel of the Black Regiment: The Life of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, by Howard N. Meyer (1967), Strange Enthusiasm: A Life of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, by Tilden G. Edelstein (1968), and White Heat, by Brenda Wineapple (2008).

Critical literature is scarce, owing to the fact that Higginson has largely been ignored since his death. A positive assessment by Van Wyck Brooks in New England: Indian Summer (1940) stimulated the writing of several biographies, noted above. James W. Tuttleton in Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1978) traces the Transcendentalist influence. Stow Persons in Free Religion (1947) discusses his role in the Free Religious Association. Leigh Eric Schmidt examines the influence of Higginson’s “The Sympathy of Religions,” in Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality (2005). Sandra Harbert Petrulionis in To Set This World Right: The Antislavery Movement in Thoreau’s Concord (2006) frequently mentions his abolitionist activities.

Article by Barry Andrews

Posted March 24, 2015