William Phillip Jenkins (October 28, 1911-December 13, 1985) was a Unitarian minister active in denominational leadership. He was influencial in the development of Unitarianism in Canada after World War II and active in the 1961 consolidation of the Unitarians and the Universalists. His forceful views on religion and social issues were a staple of Canadian newspapers, radio, and television in the 1950s.

Born in Columbus, Ohio to Alma and Clifford Jenkins he was the elder of two sons. His father, who worked as a collector and superintendent at a freight transfer company, came from a Welsh background while his mother’s parents were from central Europe, either Austria or Hungary. The family attended a Columbus church affiliated with the German Evangelical Synod.

Jenkins went to Ohio State University (OSU) and graduated in 1932 with a B.A. in political science. The following year he attended the OSU law school but withdrew during the Great Depression. Returning to school, he attended Eden Theological Seminary in Webster Grove, Missouri 1935-38, where he obtained his B.D.

Eden had been a German Evangelical seminary until 1934 when the German Evangelical Synod of North America consolidated with the German Reformed church to form the Evangelical and Reformed Church (E&R). After graduation, Jenkins returned to Columbus, Ohio as associate minister at St. John’s E&R church where he was ordained on June 19, 1938. That fall he transferred to a missionary church in Jacksonville, Florida. In 1938 during his ministry in Jacksonville, he married Marie Norman. When missionary funds were withdrawn, they moved to Milbury, Ohio where he was pastor at St. Peter’s E&R church, 1939-41. Their first child, Karen was born during their time in Milbury. Two more children, David and Anne followed a few years later.

During his ministry in Milbury, Jenkins met with Lon Ray Call, secretary of the Western Unitarian Conference to discuss entering into Unitarian fellowship. He applied in March, 1941 and was granted preliminary fellowship. Jenkins was soon called by the Unitarian church in Walpole, New Hampshire where he started on December 7, 1941.

Jenkins was called by the First Unitarian Congregation of Toronto, Ontario in 1943. He found a congregation of 123 members in a 100-year-old building located in a deteriorating neighborhood near the center of downtown Toronto. Under Jenkins’ leadership the congregation grew to more than 800 members over the next 15 years. The church relocated to a better neighborhood and built a new building. Often quoted in the media, Jenkins became the best known Unitarian in the country. He also rekindled the Canadian Unitarian movement and was active in national, provincial, and local civic groups.

An outspoken religious humanist with little patience for myth and allegory, Jenkins placed provocative ads in the Toronto daily newspapers and broadcast weekly Let’s Think Together radio programs. His forceful views on religion and social issues insured him media coverage. He was a frequent guest on television and radio shows including, Assignment, This Week, and Fighting Words.

He brought in ministers to found two successful suburban congregations in Mississauga and Scarborough, Ontario. He revived the Unitarian church in Hamilton which had closed its doors, and he founded the first Unitarian fellowship in Ontario in Saint Catharines. In 1954 and 1956 he traveled to Winnipeg, Manitoba to address the Western Canada Conference, and in 1957, he revived The Canadian Unitarian, a small newsletter circulated nationally to Canadian churches and fellowships. This contributed to the creation of the Canadian Unitarian Council in 1960. At his memorial service, he was characterized as “the Moses of Canadian Unitarianism.”

During his years in Toronto, Jenkins served a term as secretary of the Canadian Institute of International Affairs, as board member and several times program chair of the Canadian Institute of Public Affairs (bringing him into personal contact with such prominent Canadians as Lester B. Pearson), director and one-time treasurer of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, and as board member, and three years as president of the Neighborhood Workers Association of Toronto.

In the Unitarian denomination, he served as president of the Meadville Unitarian Conference, 1949-51, as a member of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) Extension Committee, 1953-54 and as its chair, 1954-61. He served as President of the Unitarian Ministers Association, 1956-58. He served on the AUA Board as vice president for Canada, 1955-56, and as a Board member, 1956-61. When the AUA consolidated with the Universalist Church of America in 1961, he became the first president of the Unitarian Universalist Ministers Association,1961-63; and served on the board of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, 1961-69. He also was a member of the UUA Merger Coordination Committee, 1961-62, and on the UUA Committee on Ministerial Education, 1961-62.

Jenkins looked back on the 1950s as “the most significant in my life as a minister.” Strong-willed and outspoken, by 1959, he had had one too many arguments with the Toronto congregation. He resigned when the church board reinstated the Director of Religious Education that he had dismissed. His parting comments about “Canadian-American relations,” were widely covered in the media. He said that Canadians were becoming more nation-conscious but that they had an “inferiority complex” and still tended to rely on U.S. periodicals and television. Not one to mince words, he compared the Quebec government to Huey Long’s, called Newfoundland’s Premier a “small-time dictator,” and said Canada was full of “self-righteous citizens whose only deep devotion was to the dollar.” In Toronto he left behind a thriving congregation of eight hundred housed in a large modern building at a visible crosstown location.

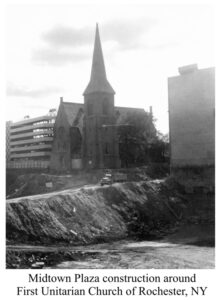

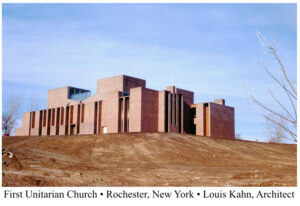

Jenkins moved to the pulpit of the First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York in May, 1959. David Rhys Williams, Rochester’s minister for 30 years, was elevated to minister emeritus but remained active in the church. When Jenkins arrived, the Rochester congregation was under pressure to sell their downtown property to the “Midtown Plaza Project,” a popular urban renewal scheme. As demolition crews surrounded the old church, David Rhys Williams staged a last minute prayer vigil hoping to save the historic Susan B. Anthony Memorial Chapel, but the developers prevailed, the church was torn down, and the congregation was forced into temporary quarters for the next three years. Evicted from downtown, the congregation hired architect Louis Kahn to design a new building in a suburban location. Jenkins helped shape its remarkable design through a series of discussions with the architect. In Rochester he was active in the peace movement, supported Planned Parenthood, and was one of the founders of Audiences Unlimited, an organization created to fight censorship. Once again, friction developed between the minister and lay leaders of the congregation. Church members wanted a minister who was a strong administrator but some lay leaders thought he was exercising too much power. Ministering to a congregation housed in temporary quarters, following a popular minister of 30 years, while designing and building a new church and wrangling with the board over his duties and his contract led Jenkins to tender his resignation once again.

He returned to Canada in 1962 as the minister at Hamilton, Ontario; a smaller congregation housed in a more modest new building. Since Hamilton was a half time ministry, there was an effort to work out a simultaneous appointment as Executive Director of the Canadian Unitarian Council (CUC). After that fell through in 1964, he accepted a call from the First Unitarian Church in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He dramatically demonstrated his forceful ways in Winnipeg. One Sunday morning the congregation arrived to find the new chancel front of the sanctuary removed, the old Victorian front and organ revealed, and the pews sold and replaced by movable chairs. Only a few members of the church board had been consulted. The congregation grew during Jenkins ministry.

He returned to Canada in 1962 as the minister at Hamilton, Ontario; a smaller congregation housed in a more modest new building. Since Hamilton was a half time ministry, there was an effort to work out a simultaneous appointment as Executive Director of the Canadian Unitarian Council (CUC). After that fell through in 1964, he accepted a call from the First Unitarian Church in Winnipeg, Manitoba. He dramatically demonstrated his forceful ways in Winnipeg. One Sunday morning the congregation arrived to find the new chancel front of the sanctuary removed, the old Victorian front and organ revealed, and the pews sold and replaced by movable chairs. Only a few members of the church board had been consulted. The congregation grew during Jenkins ministry.

Manitoba winters were too cold for his wife Marie, so in 1968 they moved to Chicago, Illinois. Preston Bradley had been the minister at The People’s Church of Chicago for 58 years, so Jenkins assumed he was being called to lead the congregation. Bradley, on the other hand, continued to exercise control as Senior Pastor. After eighteen months, Jenkins had had enough.

When he moved back to the Toronto area in 1970, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper welcomed him back to Canada with the headline, “Radical cleric back in Toronto.” When the reporter accused him of having a messianic complex, Jenkins replied, “Hell, I don’t want to ‘save’ anything. All I want to do here is the only thing I’ve ever been able to do. And that is to help people help themselves.”

Jenkins closed his career with a series of interim ministries; Madison, Wisconsin, 1973-74; Brookfield, Wisconsin, 1974-76; Wellesley Hills Massachusetts, 1976-77; and Franklin, New Hampshire, 1977-78. He divorced his first wife in 1975 while serving in Brookfield and subsequently married Marie House.

In retirement, he returned once again to Canada where Toronto’s First Unitarian Congregation made him Minister Emeritus in 1984. Toronto was the city he loved, and it was close to the Peterborough, Ontario summer cottage where there was fishing, boat rides to take, people to visit, paths to walk, and lifeless young saplings to uproot and fashion into canes.

Ministerial files for Jenkins are in the archives of the Andover Harvard Theological School Library in Cambridge, Massachussetts. They also have copies of pamphlets and sermons that he wrote including; A Fellowship of Seekers (1954), Black Muslim and White Birch (196-), The importance of being yourself (19–), Let’s think together (1955), The mold is always broken (1950), Unitarians Believe (1963), The Voice of the people and the voice of God (1944), and What Are You Giving for Christmas? (1961). Additional archive materials are held at the First Unitarian Church of Toronto, Ontario.

Phillip Hewett, Unitarians in Canada (1978) provides some details of Jenkins’ life and an overview of Unitarianism in Canada. Two conference presentations; Donna Morrison-Reed, The Tale of Two Bills and the Gospel According to St. John, (2000); and Richard Gilbert, Rochester’s Alert Conscience and Hospitable Roof (2002); along with a sermon by Charles Eddis, Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? (2007), are available on the Internet.

Article by Charles Eddis

Posted February 15, 2012