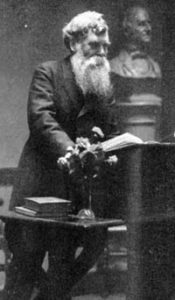

Jenkin Lloyd Jones (November 14, 1843-September 12, 1918), a pioneering Unitarian minister, missionary, educator, and journalist, expanded the ranks of midwestern Unitarians and built up much of the structure of the Western Unitarian Conference. He founded a major program church in Chicago, All Souls, together with its associated community outreach organization, the Abraham Lincoln Centre. A radical theist, he tried to move Unitarianism away from a Christian focus towards non-sectarian engagement with world religion. Later in life, during a time of popular enthusiasm for war, he was a prominent pacifist.

Jenkin, or “Jenk,” the seventh of ten children of Richard Lloyd Jones and Mary (Mallie) Thomas James was born near Llandysul, a farming town in Cardiganshire. This part of Wales, the “Black Spot of Unitarianism,” had a dozen Welsh Unitarian congregations within a thirty-mile area. The family attended the Unitarian church in Pantydefaid. Nine of Jenk’s uncles were Unitarian ministers. His father farmed, made hats, and occasionally conducted church services. In 1844, when Jenk was a year old, the Jones family emigrated to the United States, joining Richard’s brother, Jenkin, in Ixonia, Wisconsin. (The Jenkins were named after Jenkin Jones (1700-1742), the founder of the first Arminian church in Wales.) Uncle Jenkin, who worked at a sawmill to support his brother’s family while they cleared land for a farm, died of malaria in 1846. Many years later the younger Jenkin mourned: “There is a void in my heart for the uncle I cannot remember, whose bravery has been a lifelong inspiration and responsibility.”

Although they did not share all of its beliefs, the Jones family was invited to join the local Ixonia church. After visiting ministers complained about the Jones “heretics,” and Richard Lloyd Jones refused to resign his membership, a heresy trial was held. Jones won his case by pointing out that his family had been invited to join the congregation even after they had stipulated that they could not subscribe to the creed. When the frustrated judges began to discipline the minister who had admitted them, the Joneses resigned and held their own services. A churchgoing family, they nevertheless continued to attend the community worship.

After ten years in Ixonia, the Joneses moved to Spring Green in the Wisconsin River Valley, where, for lack of something more liberal, they attended the German Baptist church. Often critical of what they heard in church, and perceived by neighbors as high-handed, the family was known locally as “the God-Almighty Joneses.”

Jenkin was passionately interested in getting an education. He resented missing lessons at the Spring Green Academy to help on the farm. He avidly read all the newspapers and journals—including the New York Tribune and the Atlantic—that came into the household. In 1862 he joined the Union Army. He served as a private with the 6th Battery, Wisconsin Volunteer Artillery, fighting in eleven battles, including Vicksburg, Lookout Mountain, Chattanooga, Missionary Ridge, and the siege of Atlanta. Because his foot was broken at Missionary Ridge, he afterwards had to walk with a cane. Convinced by his experience in the army that people needed to find better ways than war to settle differences, he became a lifelong pacifist.

After being mustered out of the army, Jones helped on the farm and taught school until one day, inspired by “some sort of spiritual explosion,” he announced to his family his wish to become a minister. As his father had long regretted not sending him back to Wales to study for the ministry with his great-uncle, David Lloyd, this choice of vocation precluded any opposition to his leaving the farm to pursue higher education.

In 1866, ill-prepared academically and socially, and never having attended a Unitarian church, Jones entered Meadville Theological School in Meadville, Pennsylvania. He began his studies in their Preparatory Division, getting a basic arts education. His classmate Charles W. Wendte, described him as “a genuine Western boy, unspoiled, uneducated, poor but earnest, persevering and as bright and keen as you could desire.” By the time he graduated, he was an acknowledged leader in his class. He and his classmates, many of whom were also Civil War veterans, discussed the new European Biblical criticism, non-Christian religion, social reform, and evolution. His commencement paper, “Theological Bearings of Development Theory,” dealt with the implications of evolution for ideas about God. He developed his knowledge of science and of world religions more fully through private reading during the years following seminary.

At Meadville, Jones met Susan Charlotte Barber, private secretary to Professor Frederic Huidekoper. She guided and encouraged Jones’s interest in art and literature. They married in 1870, immediately after his graduation. They soon after had two children, Mary and Richard Lloyd Jones. Jenkin and Susan spent their honeymoon in Cleveland, Ohio at the annual meeting of the Western Unitarian Conference (WUC). That fall, soon after they arrived in Spring Green, Jones’s mother died. At a service after her funeral, at home, Jones began his ministry by presiding over his family’s first communion in America.

In 1870 Jones was ordained as the minister of the Liberal Christian Church in Winnetka, Illinois, just north of Chicago. As he felt the position limiting, he stayed less than a year. He returned to Wisconsin to work as a traveling missionary and also served the First Independent Society of Liberal Christians in Janesville, Wisconsin, 1871-80. As state missionary he developed Unitarian societies in Racine, Madison, Baraboo, and Whitewater.

Jones’s preaching gained power with practice. He also gradually shifted from giving sermons that were Biblical, exegetical, and self-consciously Christian, to giving educational and inspirational addresses based upon a variety of texts, events, or ideas.

During Jones’s years at Janesville, there was tension between the churches of the WUC and the conservative New England leaders of the American Unitarian Association (AUA), who didn’t want their missionary money to fund radical ministers and churches in the West. At the 1872 meeting of the WUC, Jones proposed that “It would be much better for the West if the Association dropped [sending money] entirely and we were obliged to raise our missionary funds ourselves!” In 1874, in a paper presented to the WUC, “Missionary Methods in the West,” he outlined a decentralized structure and proposed the position of Western Secretary to communicate and “incarnate cheer” in local western churches. In 1875 the WUC voted to have no doctrinal test, to collect its own missionary money, created the part-time position of Missionary Secretary, and hired Jones.

As Missionary Secretary, Jones was a leading promoter of Unitarianism in the West. Each year between 1875 and 1882 he traveled 10-25,000 miles, going as far away as California, at first drawing on his own resources to supplement his transportation money. He made an effort to attend all conferences, installations, ordinations, and dedications. He corresponded with candidates and churches, helping to get ministers to fill the vacant pulpits. Because of the authority he gained through his efforts, and his ubiquity, he was sometimes affectionately dubbed “Bishop,” or even “Archbishop.” Less grandly, in 1882 the Unitarian minister in Lawrence, Kansas, Clark G. Howland, called him “the Lord’s chore boy and the chore boy of the Western ministers and laymen.”

In 1876 Jones became Corresponding Secretary of the WUC, a position on the Executive Council and, effectively, the WUC liaison to the AUA. In 1878 he was elected to Board of Directors of the AUA. He attended a few of their meetings (in the east) and acted as the sole representative of western interests. He was frequently in conflict with AUA leadership and staff over mission policies. While the AUA targeted large cities and college towns and provided funds to congregations in those places to buy or construct church buildings, he hoped to “broadcast” the message of liberal religion as widely as possible and in any possible venue. He dreamed of creating a rural and small town groundswell for a religion that would transcend Christianity and other existing religions. To do this he proposed to use available funds, not for buildings, but to hire missionaries and to pay their travel expenses. Against received wisdom, he targeted as potential Unitarians not only migrating Yankees, but liberals from other immigrant groups. Accordingly he sponsored the work of the Norwegians Kristofer Janson and Hans Tambs Lyche, the Dutch Frederick Hugenholtz, and the Dane F. W. Blohm.

In 1878 Jones helped to found the liberal religious and reform weekly, Unity. The following year, he became editor, a job that he retained for the rest of his life. The masthead principles of Unity were “Freedom, Fellowship, and Character.” On the editorial board with him were William Channing Gannett (co-editor), James Vila Blake, Henry Martin Simmons, John Learned, and Frederick L. Hosmer. This group, known as the “Unity men,” guided the magazine until 1892, helped to clarify Jones’s thinking, and supported his missionary goals. Together, they opposed basing Unitarian fellowship upon any doctrine whatsoever, but defined it as the common effort to improve human life.

During his secretaryship Jones established a Chicago, Illinois headquarters for the WUC. He expanded it into a joint headquarters for the WUC, WWUC, the Western Unitarian Sunday School Society, and Unity. He hoped to develop the WUC into an organization the equal of the AUA, and having the same tools and resources.

At first Jones found his missionary labor, combined with his Janesville pastoral responsibilities, “a perfect joy, an intoxicating delight.” In 1880, after the strain had begun to tell on his health, he planned to resign as missionary. Forestalling this, the Conference voted to make the Mission Secretary a full-time position. Jones then resigned from the Janesville church and moved to Chicago, to be based at the new WUC headquarters. When they arrived, he told his wife, “We will build a church here in Chicago.”

In 1882, needing further rest from his physical labors, Jones was relieved of his traveling responsibilities and made part-time coordinator of missionary activity, working principally in the Chicago office (though he still attended ordinations etc. and preached in small towns upon request). At the same time he was given a gift to pay his expenses for a long vacation in Wales. He preached throughout Wales and made connections there with family and other Unitarians, which he afterwards maintained. He also toured elsewhere in Britain and continental Europe, looking at literary locations and art.

Returning to Chicago, Jones gathered in a rented hall the twelve remaining members of an almost extinct congregation, Fourth Unitarian Church. Attendance grew rapidly, at first exponentially. Soon after, in early 1883 he reorganized it as All Souls Church. In 1884 he resigned as secretary of the Western Unitarian Conference to serve, for the rest of his life, as the minister at All Souls.

When Jones started working for the WUC, it had 43 member societies which had a collective debt of $100,000. By 1884 there were 87 societies, which collectively owed only $7,000. There were seven state conferences, each of which had at least a part-time missionary. Jones recorded that in the nine years he had served the WUC he had traveled 122,370 miles and preached 1,370 times.

In 1886 the thriving All Souls congregation moved into a new building, combining church, parsonage, school, and clubhouse. Because of his dynamic preaching there was standing room only on Sunday, and often hundreds were turned away. To reach a wider audience, he gave a series of sermons on “Practical Piety” at the Central Music Hall on Saturday nights. Jones gave regular weekday lectures on philosophy, literature, science, and his war experiences. He also made March lecture tours in the South. His literary gospel was: “And now abideth these four: Emerson, Browning, George Eliot, Lowell; and the greatest of these is Emerson.”

In 1886 Jones became a charter member of the Chicago Peace Society and, with William Channing Gannett, published a book, The Faith that Makes Faithful. In 1887 he helped found the Chicago Institute for Instruction in Letters, Morals, and Religion and became a trustee of Antioch College. He helped begin the Post Office Mission, an early form of The Church of the Larger Fellowship, which mailed sermons and tracts to people living far from any Unitarian church.

Jones’s ties to family and the Wisconsin River Valley remained strong. There, on Tower Hill, with the help of his brothers, he founded a retreat center for city ministers and families. In 1890 this became the Tower Hill Summer School of Literature and Religion. For two months each summer, he vacationed in the country and used the Summer School as a channel for his energy. Worship was held in Unity Chapel, which the family had built near Tower Hill. He named himself its “Permanent Non-resident Minister.”

Beginning with Mary Safford, Jones promoted women in ministry and helped to make theological education easier for them. Women ministers, a number of whom where known as the “Iowa Sisterhood,” loyally supported his missionary policies. He gave lectures that addressed the role of women in the home and in society. Eleanor Elizabeth Gordon recalled his lecture on Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House as “a plea for recognition of womanhood as womanhood. Womanhood first, this being right, wifehood and motherhood would take care of themselves.” In his later years Jones campaigned for votes for women, billing himself as “America’s aboriginal suffragist.”

Jones was the general secretary of the group that planned the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, held in Chicago. To raise enthusiasm for the enterprise he preached a series of sermons, “Glory of the Parliament.” Many of its 4,000 attendees encountered non-Christian religions for the first time. Fannie Barrier Williams, a black member of Jones’s congregation, delivered an address entitled, “The Religious Mission of the Colored Race.” Participants came away from the Parliament feeling that the world was entering into a new era of cooperation between religious groups.

In the early 1890s the Unitarian National Conference sought reconciliation with the Western Conference. Although the preamble to its constitution declared that the churches “accept the religion of Jesus,” it also allowed that “nothing in this constitution is to be construed as an authoritative test.” This wording ended theological controversy for many. Jones, nevertheless, felt that it constricted the meaning of Unitarianism and precluded the fulfillment of his vision of a world-spanning religion. Although All Souls remained in the WUC, Jones shifted his attention away from the Unitarian organization and joined the organizing committee of the American Congress of Liberal Religion, an alliance of liberal Jews, Unitarians, Universalists, and Ethical Culturalists. Their goal was a “Church of Humanity, democratic in organization, progressive in thought, cherishing the spiritual traditions and experiences of the past but keeping itself open to all new light.” Jones served as its General Secretary, 1894-1906.

“Jesus wrote no creed, appointed no bishop, organized no church and taught no trinity,” wrote Jones. “Taking these away, you have instead of Christianity only a blessed humanity left.” He explained that “Jesus is unintelligible except to him who brings his human experience to the study of his character, and to such study, Jesus becomes a benignant spirit, a sustaining master, a reclaiming and redeeming spirit.” It is up to us, he thought, go try to go beyond what is given us: “Reverence lies not in the acceptance of dogma bequeathed to you, but in the receptive spirit, the truth-seeking attitude.” He found that “religion is a verity best understood when least defined.” What we will find in our search, he thought, is not creeds to protect, but deeds to accomplish. And, he discovered, “In ethics all religions meet.”

The many religions of the world have all something to offer us, and something for us to respect. Jones wrote, “nothing in this great world stands alone” and “the religions of the world are measured by their expanding sympathies, their widening alliances.” “Pitiable is the spirit that is afraid of contamination by contact with a spirit of a different creed from its own, a mind with a different philosophy from its own, a man or a woman who walks a different social round from his own. Most pitiable of all is the soul that is afraid of another soul encased in a skin more white, or black, or yellow than its own.”

Jones appealed to his Unitarian colleagues to join the Congress of Liberal Religion. Although many shared his ideals, they were not ready to invest their futures in this vaguely-defined nonsectarian Congress. Taking their hesitancy as a personal rejection, in 1898 he and All Souls church declared themselves “undenominational.” Relations between Jones and the WUC worsened when the Conference voted to replace Unity as its official publication with a monthly magazine, Old and New. In the pages of Unity Jones vented his anger at what he saw as the defection of his friends. Many of the women ministers he had supported were distressed at this break with their champion and sought reconciliation. They tried to demonstrate their solidarity with him by naming new churches either “All Souls” or “Unity.”

In 1891 Jones and All Souls purchased land for a new building, the Abraham Lincoln Centre, to house both the church and social services. The Centre was finished in 1905. It had a gymnasium, reading rooms, libraries, and rooms for manual training, domestic science classes, and other classes. Six thousand people a week passed through its doors. In sermons based on his experiences in the Civil War, Jones frequently used metaphors likening his congregation and the workers at the Abraham Lincoln Centre to an army.

Abraham Lincoln, for whom the Centre was named, remained throughout Jones’s life, one of his greatest heroes. “He is a prophet of religion and morals,” Jones proclaimed. “He belongs to humanity because his soul was profoundly religious, in league with justice, dedicated to that love which is not only human but humane.”

Between 1886 and 1915 Jones was active in more than 20 associations and reform movements. He was the founder and first president of the Illinois State Charities, vice president of the American Humane Society, a board member of the Poetry Society of America, honorary vice president of the Anti-Imperialist League, leader of the Anti-Saloon League of Chicago, director of the Non-Smokers Protective League, a charter member of the Civic Federation of Chicago, and founder of the Helen Heath Settlement House. He lectured in English at the University of Chicago and at Meadville, where he also served on the board. He was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society in 1895.

Susan died in 1911. In 1915, at 72, Jenkin remarried. His second wife, Mrs. Edith Lackersteen, had been a co-worker at the Abraham Lincoln Centre for many years.

Most of Jones’s Unitarian contemporaries were advocates of peace, but within limits. Churches held yearly patriotic and war memorial services, although ministers generally called war at best a necessary evil. Jones, and others, had voiced concern about the Spanish American War and America’s intervention in the Philippines. He believed in evolution, in progress, and saw war as a step backwards for humanity. “War is deplorable in any aspect,” he wrote, “and the existence of it is an arraignment of humanity and reproach to the religion that tolerates it.” After the First World War began, during the period of American neutrality, Jones hoped that peaceful means might yet end the hostilities and usher in an era of permanent peace. He traveled across the country speaking to legislative assemblies, university and church audiences, and at public meetings.

In 1915 industrialist Henry Ford sponsored an international conference in Stockholm to discuss ways to end the war, hiring a ship to transport a delegation of 150 Americans to Europe. He prevailed upon Jones to join the venture. Although Jones doubted the mission’s success, he felt called to act upon his belief that if people could start wars, then people, working hard enough, could end them. Without the participation of the nations that were part of the hostilities, no binding resolution was possible. The press did not report sympathetically on the voyage of the “Peace Ship.” One of the most widely circulated photos in American newspapers was of Jones playing leapfrog on deck. Back home in Chicago, Jones said, “So here I stand, as I stood before I went, confirmed and strengthened in my convictions by the experience of the last three months.”

Jones thought that people could be persuaded to embrace pacifism. In 1917, during the weeks preceding the entry of the United States into war, he went on a month-long lecture tour, speaking wherever people would listen. Reflecting upon the Civil War, in which he had participated, he said, “the thing done was worth the cost but it was the wrong way to do it.” As the United States entered the European conflict, Jones found himself increasingly alone in opposing the war. Disappointed in the Chicago Peace Society’s silence, he withdrew his membership. While others were caught up in the tide of patriotism or did not speak up for fear of reprisals, he stood openly against this or any future war.

Denominations throughout the country, including the American Unitarian Association, threatened congregations that didn’t support the war with loss of financial support. Although most ministers who opposed the war lost their positions, Jones remained at All Souls and in 1917 celebrated his 35th year with the congregation.

In the pages of Unity, Jones urged people to write open letters against the war, to circulate petitions, and to send telegrams to Congress. As he wrote to his wife, “The bands, bugles and shoulder straps have the hour, but peace has the century and we must work for that.” In 1918 Chicago’s postmaster, citing the Emergency Act of 1917, prohibited the distribution of Unity through the mail. Jones petitioned to have the suspension lifted. A few months later, at Tower Hill, and in rapidly failing health, he read the first issue of Unity printed after the suspension was lifted. Immediately afterwards he fell into a coma and died the same day.

Death

The Spring Green Post of the Grand Army of the Republic escorted his body to the churchyard of Unity Chapel. There he was laid to rest. “When the wheels of life bear me down for the last time,” Jones had written, “I ask for no higher compliment, I seek no truer statement of the work I have tried to do than the white-headed old negress gave the beardless boy [Jones] on the hot Corinth battlefield in 1862. Then if I deserve it, let someone who loves me say, ‘Here is a Linkum soldier who done got run over’—one who like his leader tried to pluck a thistle and plant a flower wherever a flower would grow.”

Sources

The Jenkin Lloyd Jones Papers are at Meadville/Lombard Theological School in Chicago, Illinois and in the archives at the University of Chicago Regenstein Library. Jones works include a debate with J. P. Bates, Liberal Religion: What It Means and What It Is Worth (1874); Practical Piety (1887); Religions of the World (1893); Tobacco, the Second Intoxicant (1893); The Word of the Spirit to the Nation, Church, City, Home and Individual (1894); Ten Noble Poems in English Literature (1897); Jess, Bits of Wayside Gospel (1899); Search for an Infidel (1901); Nuggets from a Welsh Mine (1902); The Reinforcements of Faith (1905); Love and Loyalty (1907); a sermon with John T. McCutcheon, What Does Christmas Really Mean? (1908); An Artilleryman’s Diary (1914); Love for Battle-Torn Peoples: Sermon-Studies for the Reinforcement of Faith (1916); Prayers (1927); and, of course, much in the journal Unity. From 1895 until his death, Jones worked on a collection of sermons on the lessons to be learned from the hardships and rewards of rural life. The unfinished work was edited and published long after his death by Thomas E. Graham as The Agricultural Social Gospel in America: The Gospel of the Farm (1986).

A bit of autobiography is “Jenk’s Story,” in Thomas E. Graham, ed., Trilogy: Through Their Eyes (1986). There is a biography, Richard Harlan Thomas, “Jenkin Lloyd Jones: Lincoln’s Soldier of Civil Righteousness” (Rutgers thesis, 1967), and biographical entries in David Robinson, The Unitarians and the Universalists (1985); American National Biography (1999); and Mark W. Harris, Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism (2004). There are obituaries in Unity (September-November 1918). Samuel A. Eliot’s Heralds of a Liberal Faith, volume 4, contains a chapter on him by Richard D. Jones. A biography of Jones is integrated in Charles H. Lyttle, Freedom Moves West (1952, reprinted 2006). More detail about his WUC years (and early life) can be found in Thomas E. Graham’s articles, “The Making of a Secretary: Jenkin Lloyd Jones at Thirty-one,” Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1982-83) and “Jenkin Lloyd Jones and the Western Unitarian Conference, 1880-1884,” Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1989). Graham’s Unity Chapel Sermons 1984-2000 (2002) and Maginel W. Barney, The Valley of the God-almighty Joneses (1986) deal with Jones and his family. For the Welsh background of the Jones family, see D. Elwyn Davies, “They Thought for Themselves,” A Brief Look at the History of Unitarianism in Wales and the Tradition of Liberal Religion (1982) and David Russell Barnes, People of Seion (1995). See also Arnold Crompton, Unitarianism on the Pacific Coast: The First Sixty Years (1957); Barbara S. Kraft, The Peace Ship: Henry Ford’s Pacifist Adventure in the First World War (1978); Mark D. Morrison-Reed, Black Pioneers in a White Denomination (1980); and Cynthia Grant Tucker, Prophetic Sisterhood (1990).

Article by Cathy Tauscher and Peter Hughes

Posted September 20, 2007