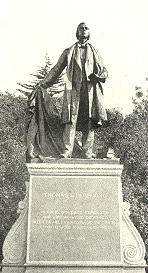

Thomas Starr King (December 17, 1824-March 4, 1864), a Universalist and a Unitarian minister, was a lecturer and orator whose role in preserving California within the Union during the Civil War is honored by statues in the United States Capitol and in Golden Gate Park in California. Two mountains are named for him, one in New Hampshire’s White Hills; another in the Sierra Nevada of California.

Thomas Starr King (December 17, 1824-March 4, 1864), a Universalist and a Unitarian minister, was a lecturer and orator whose role in preserving California within the Union during the Civil War is honored by statues in the United States Capitol and in Golden Gate Park in California. Two mountains are named for him, one in New Hampshire’s White Hills; another in the Sierra Nevada of California.

Barely five feet tall and physically fragile, King was undistinguished in appearance. Well into his thirties he appeared no older than a youth. His energy and magnetism as an organizer, minister, and preacher, however, quickly impressed any who had mistakenly judged him by appearance. “But, though I weigh only 120 pounds,” he remarked late in life, “when I am mad I weigh a ton!”

Starr King was born to Thomas Farrington King and Susan Starr King in New York City in December, 1824. He was named after his maternal grandfather Thomas Starr, an immigrant from the Rhineland. His family called him “Starr.” At the time of his birth, his father was an itinerant Universalist minister in based in Norwalk, Connecticut. An eloquent and outgoing preacher, Thomas F. King soon afterwards found a settlement in Hudson, New York. In 1828, King was called to the larger Universalist church in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and in 1835 he moved his ministry, and his family, to Charlestown, Massachusetts, just across the Charles River Bridge from Boston.

Starr was a precocious child. His parents encouraged him in habits of industrious study. They were delighted when he early proclaimed his desire to be a minister like his father. By the age of thirteen he already had a published sermon. The death of his father when Starr was only fifteen years old, however, made it impossible for him to attend college or divinity school. He took up the responsibility of providing for his mother and siblings and went to work.

One of his jobs, and the one he liked best, was as bookkeeper in the Charlestown Navy Yard. His wages were enough to support the family and the hours of work allowed him to attend lecture courses at Harvard College. He sought opportunities to hear good preaching and studied assiduously on his own. Among the Universalist ministers who helped and encouraged him during his period of unofficial study were Hosea Ballou 2d, a friend of his father whom Starr called his “theological father,” and Edwin H. Chapin, his father’s successor at Charlestown. During this time Theodore Parker promoted him and provided him with preaching opportunities. He never completed a degree program. Yet he qualified himself for the professional ministry by means of independent study. Many years later, when he received recognition for his preaching and public speaking abilities, he would refer to himself as “a graduate of the Charlestown Navy Yard.”

In 1846, the twenty-one year old Starr King accepted a call from the Charlestown Universalist Church. Though hesitant to serve the same congregation his father had so successfully served, King was eager for the challenge of parish ministry. In the event, he found the situation an uneasy one. “Preaching to aged men and women who have seen me as a boy in my father’s pew,” he admitted, “I necessarily cannot command the influence which a stranger would wield.”

The following year King met Henry Whitney Bellows, minister of the First Unitarian Church of New York, upon whom he made such an impression that Bellows immediately sought to have King called by New York’s Second Unitarian (Church of the Messiah). Although King’s preaching pleased the congregation, the trustees balked at calling a young minister without official educational qualifications. The church offered him only the probability of an offer, if he undertook a year of study at the theological school at Cambridge. King refused such terms. When he returned to Charlestown, however, he took with him letters of introduction from Bellows which provided him a wider access to Unitarian notables in Boston.

Another Unitarian opportunity was not long in coming. The Hollis Street Church, reduced in size after losing many members as the result of a controversy over the decided antislavery and temperance stand taken by the previous minister, John Pierpont, made King an offer in 1848. When King agreed to serve the Hollis Street Church, it seemed to many that he was changing denominations and deserting his old faith. But his embrace of a broad ecumenical religion included Unitarians without repudiation of his Universalism. Questioned about this, King responded with the blend of intelligence and humor which marked all his prophetic ministry. He said, “The one [Universalist] thinks God is too good to damn them forever, the other [Unitarian] thinks they are too good to be damned forever.” According to King, the only reason that Unitarians and Universalists had not already joined together was that they were “too near of kin to be married.”

Days after he was installed at Hollis Street, Starr King and Julia Wiggin of East Boston married. Their family eventually included daughter Edith and son Frederick. Starr also continued to support his widowed mother and a chronically ill brother. His $3000 yearly salary from the Hollis Street Church would not stretch far enough.

The popular lecture circuit was a natural choice to supplement King’s funds. He had begun lecturing in 1847. By the 1850s he had entered the ranks of the most respected and popular platform speakers of the time. His friend Henry Whitney Bellows compared him favorably to such well-known orators as Wendell Phillips and Henry Ward Beecher. “He is witty,” Bellows noted, “and just profound enough to be intelligible to people who cannot enjoy any thing that does not go beyond their own ideas.” One lecture, on the German poet Goethe, struck Harvard president James Walker as remarkable. Travelling a circuit that extended from Bangor, Maine to St. Louis, Missouri, King was successful in communicating to a mass audience the thought of such men as Socrates and Daniel Webster, and attracted large crowds to hear him on such topics as “Substance and Show” and “Existence and Life.”

Over eleven years King helped the Hollis Street Church recover from turmoil and factionalism and achieve financial health. During this time the congregation grew to five times its former size. He was both a beloved pastor and a brilliant preacher. Theodore Parker called him the best preacher in Boston. His sermons, read from manuscript in a deep and resonant voice, were philosophical and literary. The goodness of God, the beauty of creation, and the progress of humankind were the inspirations King evoked in his preaching to draw people to a life of goodness. Towards the end of his pastorate, King expressed his vision for the church “as the interpreter of Christianity,” using the metaphor of the building of a great organ. “The final justification of each sect is found when we can regard it as a new stop, or class of pipes, with an original constitution and quality, to pour out some essential sentiment with nobler volume, or richer melody, in response to the glory of God.”

Because of his manifest achievement as a scholar and minister, Harvard University awarded King an honorary Master of Arts in 1850.

Worn down by years of what he called “the detestable vagrancy of lecturing,” in 1859 King sought a new position which would pay him enough so that he would have less need to augment his income, and, as he wrote Bellows, one where his labor “would be of greater worth to the general cause than it can be in Boston.” Having received several offers, including Brooklyn, New York and Cincinnati, Ohio, King chose San Francisco, California as it was, in his estimation, “the more crying call.”

In California, beginning in April, 1860, King had several ministries, one to his congregation of Unitarians on Stockton Street, another to Christians in the San Francisco area, and yet another to the people of the entire state. He helped the Unitarian church to become financially solvent and led them to build a new church building. His preaching attracted new membership, a number of people regularly travelling from the interior of California to hear him preach. Despite the effort that he devoted to Unitarian institution building on the west coast, King believed that he had a role to play in the spiritual development of the community as a whole. In his sermon, “Spiritual Christianity,” he described Christianity not as a creed or an institution, but as a spirit, a “secret agency” or force underlying many specific outward expressions. He thought that God’s spirit was to be found both inside and outside the church, in works of secular art and in private lives. He found more unity and truth in shared public expression than in the speculation of dogma and theology. “Only those elements of the faith and life of every church . . . which can be set to music,—are worthy and enduring elements.” He had a millenial vision of the emergence of a unified, and liberal, Christianity: “Our mission is to hasten the time when the church in general shall modify her creeds and grant more freedom to thought and organize more charity, and receive again into fellowship the needful forces, which her narrowness has spurned.”

King was soon drawn into the politics of his new state and became an advocate for the preservation of the union. He campaigned for the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, preaching from his own pulpit and lecturing on a tour of the mining towns of the California interior. In 1861 launched a lecture campaign in San Francisco with his address, “Washington and the Union.” He followed this with a series that included “Webster and the Constitution” and “Lexington and the New Struggle for Liberty.” He delivered these speeches in San Francisco and repeated them throughout the state. After the capture of Fort Sumter, King announced that he would give all his energy to preserving the union. Following the news of the disastrous First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), he toured with a lecture aimed against defeatism, “Peace, What Would It Cost Us.” His campaign for Republican candidates at the state level in 1861 helped elect a Republican governor and a pro-Union coalition to the legislature. According to General Winfield Scott, the Union Army commander-in-chief, Starr King “saved California to the Union.”

King was soon drawn into the politics of his new state and became an advocate for the preservation of the union. He campaigned for the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, preaching from his own pulpit and lecturing on a tour of the mining towns of the California interior. In 1861 launched a lecture campaign in San Francisco with his address, “Washington and the Union.” He followed this with a series that included “Webster and the Constitution” and “Lexington and the New Struggle for Liberty.” He delivered these speeches in San Francisco and repeated them throughout the state. After the capture of Fort Sumter, King announced that he would give all his energy to preserving the union. Following the news of the disastrous First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), he toured with a lecture aimed against defeatism, “Peace, What Would It Cost Us.” His campaign for Republican candidates at the state level in 1861 helped elect a Republican governor and a pro-Union coalition to the legislature. According to General Winfield Scott, the Union Army commander-in-chief, Starr King “saved California to the Union.”

In addition King organized fund-raising for the United States Sanitary Commission, a civilian organization, headed by Henry Whitney Bellows, charged with overseeing the health and medical care of the United States army. By the end of the war California had donated one quarter of the money received by the Sanitary Commission. The first large donation, sent by King, arrived just in time to be of use at the battle of Antietam in 1862.

While living in Boston King had often vacationed in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and had sent accounts of the scenery to the Boston Evening Transcript. These were gathered in 1860 into a volume, The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry. As he traveled in California, lecturing and hiking, King sent back east more letters to be published in the Transcript. He was particularly struck by the mountainous scenery around the Yosemite Valley, which he thought the equivalent in natural scenery of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

While living in Boston King had often vacationed in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and had sent accounts of the scenery to the Boston Evening Transcript. These were gathered in 1860 into a volume, The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry. As he traveled in California, lecturing and hiking, King sent back east more letters to be published in the Transcript. He was particularly struck by the mountainous scenery around the Yosemite Valley, which he thought the equivalent in natural scenery of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Exhausted from his labors for church and country, King contracted diphtheria. He died of pneumonia on March 4, 1864.

The Thomas Starr King papers, including King’s lectures and journals, are at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Collections of Starr King papers and letters are at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California; the California Historical Society in San Francisco, California; and at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston (in the Henry Whitney Bellows papers and the Thomas Starr King letters). His sermons and speeches are on microfilm at the Stanford University Library. There are several posthumously published collections of King’s works: Patriotism, and Other Papers, with a Biographical Sketch by Richard Frothingham (1864); Christianity And Humanity: A Series Of Sermons, edited with a memoir, by Edwin P. Whipple (1877); Substance and Show, and Other Lectures. edited, with an introduction, by Edwin P. Whipple (1877); and A vacation among the Sierras; Yosemite in 1860, edited, with an introduction and notes, by John A. Hussey (1962).

Memoirs and biographies of King include Richard Frothingham, A Tribute to Thomas Starr King(1865); Charles W. Wendte, Thomas Starr King, Patriot and Preacher (1921); Arnold Crompton, Apostle of Liberty: Starr King in California (1950); and Robert Monzingo, Thomas Starr King: Eminent Californian, Civil War Statesman, Unitarian Minister (1991). Three chapters of Arnold Crompton, Unitarianism on the Pacific Coast: The First Sixty Years (1957) are devoted to King. Walter Donald Kring’s Henry Whitney Bellows (1979) sheds light on the important relationship between Bellows and King. There are biographical sketches of Thomas F. King by Lemuel Willis in The Universalist (27 June, 1874) and by John G. Adams in his Fifty Notable Years (1883).

Article by Celeste DeRoche and Peter Hughes

Posted November 11, 2000