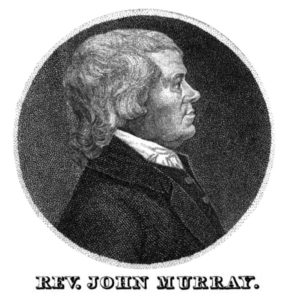

John Murray (December 10, 1741-September 3, 1815), a preacher from the British Isles, became the most widely-known and respected voice of American Universalism during the last three decades of the eighteenth century. The legal conflict surrounding his ministry was instrumental in undermining the monopoly of the established church in Massachusetts and in bringing about the legal organization of the first Universalist churches in New England. It was his vision that led to the first moves towards uniting the various independent American Universalist movements into a single denomination. While serving pulpits in Gloucester and Boston, he traveled frequently to Philadelphia and the mid-Atlantic states, being for a long time the only point of contact between Universalists there and those in New England. A friend of Generals George Washington and Nathanael Greene, and the husband of the literary pioneer Judith Sargent Murray, Murray moved in distinguished circles, which brought much-needed respectability, and a sense of self-respect, to a denomination comprised largely of shopkeepers and middling farmers. In his later years he was revered by many Universalists, including those with whom he disagreed, and regarded as primus inter pares among the generation of Universalist founders who treated him as if he were the denomination’s bishop.

The oldest of nine children, John was born in Alton in Hampshire, England. His detailed autobiography, the source of all information about his early years, does not disclose his parents’ Christian names. His mother’s maiden name was Rolt. She was affectionate, but his father, whom he described as the son of a French noblewoman and a Calvinistic Anglican, treated him strictly, even harshly. “I was studious to avoid his presence,” he wrote, “and I richly enjoyed his absence.” Fortunately his father traveled much on business.

The family moved to a place near Cork, Ireland in 1751. Here, John had an opportunity to enter an academy which would have prepared him for university education, but his father refused to let him enroll. Soon after, to supplement the family’s declining income, he was forced to take a job in business, the nature of which he never cared to mention. In Ireland the Murrays became Methodists. John became the class-leader of a group of boys.

While Murray was still in his teens, his father died, leaving him head of the household. He alleviated his family’s financial distress by winning a lawsuit over some property and taking a position as business manager to a wealthy couple, the Littles. Although he was practically adopted by his new patrons, he did not stay with them long. At this time he began preaching locally. Assured that his family could manage without him, and with some financial help from the Littles, he set out on his own to evangelize. In Cork he met the traveling revivalist George Whitefield, whose strict Calvinism pleased him more than did Methodism. He tried preaching in Whitefield’s Irish pulpit, but encountered such theological opposition that, after only a short time, he left for England.

Although his charm initially made him many friends amongst the Methodists in the west of England, his awareness of doctrinal differences and the feeling that he could not compromise his integrity kept him moving onwards to London and Whitefield’s Tabernacle. Frustrated at not finding the peripatetic Whitefield then in residence and held in suspicion by London Methodists, Murray set about making himself a success in society. After a year spent in amusement and without any gainful employment his money ran out and he began to pile up debt. To pay his creditors he took a series of disagreeable jobs in various business enterprises, including textile manufacturing. All the while he attended the Tabernacle, listened to Whitefield’s preaching, and absorbed his mentor’s non-denominational identification. He often led prayer amongst the Methodists, but feeling unprepared, he refused to preach. Around 1760 he married Eliza Neale, whose grandfather disinherited her due to his disrespect for young Murray.

Around this time James Relly, who had formerly been a preacher connected with the Tabernacle, published Union, a book which popularized his theology of universal salvation. According to Relly, every human being participated in a mystical union as part of the body of Christ, and, as part of this body, would on no account be lost. As the doctrine spread, attempts were made by the Calvinists to “rescue” those who had succumbed to this thinking. Murray was sent at the head of a delegation to bring one such young woman back into the fold. He was, however, bested in the debate. This was the beginning of a lengthy process in which Murray and his wife studied Relly’s arguments, attended his preaching, and read both Rellyan and anti-Rellyan literature, hoping to find the flaw in the optimistic Universalist reasoning. First Eliza, then John assented to the new theological idea. For this they were driven from membership in the Tabernacle.

There followed a period in which Murray experienced a series of personal losses that drove him to the brink of despair. His only son died in infancy. His wife also died and, soon after that, he learned of the deaths of four of his siblings. He was thrown into debtor’s prison. Although he was rescued by his brother-in-law and eventually paid his debts, he remained too depressed to engage in the preaching that Relly urged upon him. At that time he wished “to pass through life, unheard, unseen, unknown to all, as though I ne’er had been.” In 1770 he resolved to quit his life in the old world and start afresh in the new.

There followed an episode which has since passed into legend and become a foundational myth of American Universalism. Shortly after arriving in the American colonies, the ship on which Murray was traveling, the brig Hand-in-hand, was grounded on a sandbar and remained for a time becalmed off the coast of New Jersey, near Good-Luck Point. The captain sent Murray ashore on a foraging expedition. While gathering supplies he ran into Thomas Potter, who had built a chapel on his property to accommodate itinerant preachers. Finding out that Murray had been a preacher, and possibly learning something of the young man’s views, Potter invited him to preach from his pulpit. Murray had not intended to preach in America. That was one of the many aspects of his previous life that he sought to forget. He demurred, telling his host that he would have to leave as soon as there was a favourable wind. Nevertheless Potter extracted a promise from Murray that he would preach if his ship remained offshore on Sunday. The winds did not change, and Murray preached. Potter was greatly impressed and invited Murray to stay. Murray traveled with the ship to New York, but he soon returned to New Jersey and began a popular evangelical career.

On the basis of this dramatic story, American Universalists have marked the date of the beginning of their faith as 1770. In 1870 they celebrated their centennial, including a pilgrimage to Good-Luck Point. In fact neither Murray’s arrival nor the year 1770 was the beginning of Universalism in America. German immigrants who believed in universal salvation had already settled in the mid-Atlantic colonies. Thomas Potter himself was connected with the Rogerine Baptists, another universalist sect. Thus there was a receptive audience waiting for Murray when he arrived. This was something he would encounter again later in his career.

Another problem with 1770 as a foundational date is that Murray did not specifically preach universal salvation immediately thereafter. His evangelical success in New Jersey and Pennsylvania was based not on Universalist doctrine, which he did not emphasize, but on his general Christian message, which he delivered in a charismatic Whitefieldian manner. Often, when his more heretical convictions became known, he was driven out of town. Thus, he had little success in promoting universalism in this initial ministry.

In 1772 Murray began to extend his itinerant preaching into New England. In Rhode Island he made some influential friends, notably Nathanael Greene, who was later a General in the Continental Army. While preaching in Boston in 1774, he attracted the notice of the wealthy merchant Winthrop Sargent, who invited him to preach to a group in nearby Gloucester, Massachusetts. This group had been meeting to study John Relly’s Union, which they had obtained a few years earlier. Murray, who had earlier declined to give up his itinerant career to settle in Philadelphia, New York, Portsmouth, or elsewhere, was by this time considered anathema in most of the pulpits that had once been open to him. He was thus now more disposed to settle with a sympathetic congregation. In 1775 he served as a chaplain in the Rhode Island Brigade of the Continental Army defending Boston, having been sustained in this position by the intervention of George Washington when the other chaplains wished to have him expelled. After nine month’s service, invalided out with dysentery, Murray returned to Gloucester.

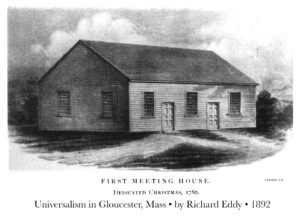

Sargent’s powerful patronage was needed, however, to prevent Murray being expelled from Gloucester as a vagrant. Then, despite his war service and patriotic fund-raising activities, Murray was labelled a seditious Englishman and brought before the Committee of Public Safety. In this matter his friendship with General Greene stood him in good stead. Finally, when direct pressure failed to force Murray to leave town, the Standing Order parish in Gloucester tried to discipline those who attended Murray’s services. A few months after Murray was suspended from the church, in early 1779 his patron, Winthrop Sargent, and fellow dissidents organized themselves as the Independent Church of Christ. The following year, they built themselves a meeting house.

An important legal challenge ensued. Taking their justification from the Bill of Rights in the 1780 Massachusetts constitution, the Gloucester Universalists withheld their parish taxes. In 1782 the parish seized and auctioned some of their personal property. This led the Universalists to sue the parish for their property and to appeal to the state for their rights. The trial, which took several years, 1783 to 1786, was ultimately settled in their favour. Murray himself did very little personally to forward the legal case, only reluctantly allowing the case to be brought in his name, and leaving it to the laity to conduct the prosecution.

Three factors embarrassed the Universalist case: 1) the society’s unincorporated status; 2) Murray’s refusal to accept a salary; and 3) the lack of an organized denominational body. The congregation ultimately remedied two of these deficiencies by voting Murray a salary in 1788, and becoming incorporated as “The Independent Christian Church in Gloucester” in 1792. Murray had set about addressing the third issue while the trial was still in progress. In 1783 he wrote to his Portsmouth, New Hampshire colleague Noah Parker of his idea for an association of Universalist churches: “Indeed it would gladden my heart, if every one who stands forth a public witness of the truth as it is in Jesus, could have an opportunity of seeing and conversing with one another, at least once every year.” Apparently unaware of the Universalist communities in such countryside places as Oxford, Milford, and Warwick, Massachusetts and Jaffrey, New Hampshire, Murray mentioned Boston, Portsmouth, and Norwich, Connecticut as possible meeting places.

During the next two years, the Oxford Universalists came to Murray’s attention. In 1785 he traveled to Oxford and, with the Philadelphia Universalist founder Elhanan Winchester, attempted to inaugurate a regular convention process for New England Universalists. Murray had reservations about Winchester’s theology and liked the Oxford area Universalists’ theology even less. Over the next two decades he visited the hill-country Universalists infrequently and sometimes avoided them even when he was traveling through their area. Thus, the 1785 Oxford convention proved something of a false start in developing an ongoing Universalist denominational organization. Nonetheless, it spurred the other Universalist communities to organize themselves more officially and encouraged them to think of themselves as part of a wider movement.

In 1790 Murray visited Philadelphia, where he helped inaugurate a more long-lived organization, the “Convention of the Universal Church, assembled in Philadelphia.” He found this group more congenial theologically than the New England Universalists, and frequently attended their annual meetings. He was often the only New England delegate to the convention, and was for a time the single thread that bound the two regions together. At the 1793 meeting of the Philadelphia Convention, “the representative from Boston—probably Murray—asked the convention for permission to form a Universalist convention in New England. Murray chaired the first meeting of the latter organization, which would later become the nucleus of the United States General Convention. He attended only two other meetings, but was on each occasion honoured as moderator.

In 1788 Murray had made a trip to England, where he was briefly reunited with his mother. After his return, later that year, he married Judith Sargent Stevens, the widowed daughter of his patron Winthrop Sargent. She was a celebrated literary figure, who was able to introduce her new husband into many distinguished social circles. Besides women’s rights she also promoted Universalism and her husband’s career. She became his literary executor and organized the publication of his works.

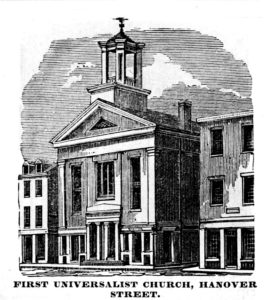

In 1794, following the death of Winthrop Sargent, the Murrays moved to Boston, where in 1785 a Universalist church had been organized with Murray as part-time preacher. In this prestigious location, as minister of a large urban church—an unusual thing in early New England Universalism—Murray assumed something of the role of a bishop in the eyes of his colleagues. For the rest of his life he was the public face of Universalism.

Since Murray was often away from his pulpit, a steady stream of country Universalist preachers tried themselves out on his Boston congregation. One such preacher was Hosea Ballou, recognized to be the leading light in the second generation of Universalist evangelists. Ballou preached for ten weeks in Murray’s absence in 1798. On the last of these Sundays, after Ballou’s sermon, Judith Murray instructed a choir member to stand up and declare, “The doctrine which has been preached here this afternoon is not the doctrine which is usually preached in this house.” Because of his respect for Murray and his knowledge of their theological incompatibility, Ballou did not attempt to settle in Boston while Murray was alive.

Murray was more pleased with another young preacher, Edward Turner, who was a friend and fellow-worker with Ballou in the central Massachusetts circuit. From 1801 to 1805 Murray tried to prepare Turner as a regular associate in Boston. Turner was at this time nearly as distant from Murray’s Rellyan theology as Ballou had been. Diplomatically preaching on neutral topics, Turner pleased Murray and caused him disappointment only when, for personal reasons, he declined to accept Murray’s invitations for co-ministry at the Boston church.

The search for an associate became more intense after 1809 when Murray suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed. For the last six years of his life he remained, as he expressed it, “God’s prisoner” and “a prisoner of hope.” The church accordingly required an associate to perform the duties that Murray could no longer manage. The great difficulty was that there were, by this time, hardly any Universalist ministers whose theology remotely resembled Murray’s. The best fit was Edward Mitchell, who was, like Murray, a former Methodist. Mitchell had started a congregation in New York City and lasted only a year in Murray’s pulpit before he was called back to his old church.

Paul Dean, a trinitarian though not a Rellyan, served as associate from 1813 until Murray’s death in 1815, and was then called to be Murray’s successor. Unfortunately a rivalry existed between Dean and Ballou, which sparked a bitter battle for the control of Universalism in Boston. This was a major factor in the genesis and development of the Restorationist controversy.

Both sides in the Restorationist controversy claimed Murray as a progenitor. He was in fact the theological father of neither party, though his Rellyan theology had some features in common with each. Murray was a Trinitarian, but not an orthodox one. Like the ancient Sabellian heretics, he portrayed God as having various modes or faces. Thus Christ is the human face of God. Christ is not, however, a mere human, but a double-natured being that contains the wholeness of God. Murray was fairly orthodox in his teaching on original sin and vicarious atonement. He believed that the sin of mankind against the majesty of God was infinite; therefore it could only be expiated by Christ, who, being God, could do so infinitely.

Murray believed that those who died impenitent would be punished in the afterlife until the Day of Judgment. At the Last Judgment, all human beings, as part of the mystical body of Christ, would be found to have their names inscribed in the Book of Life. Thus all humans would ultimately be saved, while bad angels, devils, and demons would be condemned. This demonology was an important part of Murray’s biblical theology, for according to Matthew 25, there must be a great separation of the sheep from the goats. Though he accounted all people as sheep, there had to be goats somewhere. These he found in the devil and his minions.

In a letter to a colleague (probably Edward Turner), Murray indicated how important his doctrine of evil was to his system and, in so doing, accounted for his theological estrangement from most other Universalists:

Do they really affirm there is no devil, and of course no works of the devil? What then did the Redeemer descend from the highest heavens to destroy? Doth not the sacred text declare that Christ Jesus was manifested to abolish death, and him who had the power of death, that is, the devil? But if there be no fallen angels, then all evil, moral and natural, originates from God! and there can be but one sinner in the creation, but one sinner in the universe; or there never was any sin, any transgression! What then becomes of the Bible? . . . Once more I pray you tell me whether all your associated preachers thus think, thus speak? or if happily there be exceptions, for the love of heaven, name them to me; I am pierced to the soul.

Though Murray’s theology had little influence on later generations of Universalists, he is honored today as a founder of American Universalism because of his leadership in establishing Universalism as a legitimate denomination with legal rights and a measure of social acceptability. He is also remembered as a preacher of great personal charm, appeal, and eloquence. Unfortunately, little of his eloquence has survived. His recorded preaching consists mainly of strings of biblical quotation with a minimum of original connecting material. His biographers Clarence Skinner and Alfred S. Cole lamented that it would be impossible to generate even a pamphlet made up of quotations from Murray’s writings. “Murray did not produce a single page of great literature,” they wrote, “and there is hardly a sentence of his that shows intellectual penetration of the highest order.”

The quotation most often associated with Murray, the speech containing the words, “Give them not hell, but hope,” was actually written in 1951 by one of Murray’s biographers, Alfred S. Cole. It was part of a rousing imaginary speech that Cole pictured as being delivered to Murray by “the Time-Spirit.” This bit of literary conceit was misused, or more likely misunderstood, by Henry Cheetham, director of the Department of Education of the Unitarian Universalist Association, who treated it as a quotation from Murray in a popular 1962 Sunday-school history. It has since been eagerly embraced because it offers a memorable and understandable way to characterize a figure who, for all of his importance in Universalist history, can seem somewhat remote from the concerns of modern Unitarian Universalists.

Despite the lack of memorable quotations, however, Murray is well-represented in Universalist literature in the form of stories, most of which derive from his substantial autobiography. The memoir, which takes him to the end of 1774 (it was finished by his wife Judith), concludes with an episode that portrays him as not only courageous, but ready with a bon mot. As Murray was giving a lecture in Boston, someone threw a rock through the window, intending to injure or intimidate him. Murray calmly stepped over to where the rock rested, picked it up and said, “This argument is solid, and weighty, but it is neither rational nor convincing.” Then, after his friends suggested that the situation might be too dangerous for him to proceed, he proclaimed that “not all the stones in Boston, except they stop my breath, shall shut my mouth, or arrest my testimony.”

Sources

John Murray’s works are his autobiography, The Life of Rev. John Murray (1816), completed by Judith Sargent Murray, and Letters, and Sketches of Sermons, 3 vols. (1812-13). The letters to Edward Turner are in “Letters of Murray and Richards,” Universalist Quarterly (July-October 1872). The minutes of the New England Universalist General Convention are in the Universalist Special Collections at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. The records of First Universalist Society of Boston are at the Massachusetts Historical Society. There have been no new full-length biographies of Murray since Alfred S. Cole and Clarence Skinner, Hell’s Ramparts Fell (1941). Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, vol. 1 (1979), contains a short biography and has an appendix on Murray’s writings. Murray is featured prominently in vol. 1 of Richard Eddy, Universalism in America (1884). Murray’s relationship with other Universalists is discussed in Peter Hughes, “The Origins of New England Universalism,” The Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (1997 and 1990); his search for a successor is discussed in Peter Hughes, “The Origins and First Stage of the Restorationist Controversy,” The Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2000). On Murray’s later travels, see Bonnie H. Smith, ed., Judith Sargent Murray, From Gloucester to Philadelphia in 1790 (1998). For what happened when Hosea Ballou preached in Murray’s church, see Thomas Whittemore, Life of Rev. Hosea Ballou, vol. 1 (1854). The “Time-Spirit” speech appears in Alfred S. Cole, Our Liberal Heritage (1951) and was first misattributed in Henry Cheetham, Unitarianism and Universalism: An Illustrated History (1962).

Article by Peter Hughes

Posted August 28, 2012