Theodore Parker (August 24, 1810-May 10, 1860) was a preacher, lecturer, and writer, a public intellectual, and a religious and social reformer. He played a major role in moving Unitarianism away from being a Bible-based faith, and he established a precedent for clerical activism that has inspired generations of liberal religious leaders. Although ranked with William Ellery Channing as the most important and influential Unitarian minister of the nineteenth century, he was an extremely controversial figure in his own day and his legacy to Unitarian Universalism remains contested.

Parker was born 24 August 1810 in Lexington, Massachusetts, the youngest child of a large farming family. Growing up, he attended the Lexington church. It had a long history of tolerant Calvinism and quietly became Unitarian when he was a boy. He admired the fervor of the evangelicals, however, and as a young man considered converting to Calvinist Orthodoxy.

His religious sensibility developed partly in response to domestic tragedy. By age 27 he had lost most of his family–his parents and seven of nine siblings–mostly to tuberculosis; his mother had died of the disease when he was 12. In the face of these disasters, Parker developed a strong faith in the immortality of the soul and in a God who would allow no lasting harm to come to any of His children. His firm belief in the benevolence of God led him to reject Calvinist theology as cruel and unreasonable.

Ambition also helped keep Parker a Unitarian. He dreamed of joining the Boston social elite, which was predominantly Unitarian. Intellectually precocious and driven to excel, he became a schoolteacher at 16. At 19, he passed the entrance examinations of Harvard College, but was unable to pay the tuition. He read the entire Harvard curriculum on his own. In 1832, he started an academy in Watertown. While there, he met his future wife, Lydia Dodge Cabot, youngest child of a prominent and wealthy Unitarian family.

Parker had considered a legal career, but decided to become a minister. His strong piety made the ministry appealing. Largely on his own, he studied Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, theology, church history, and biblical studies. In 1834, despite his lack of a college degree, Harvard Divinity School admitted him with advanced standing. A patron, possibly a member of the Cabot family, helped him pay his tuition.

At Harvard, Parker read voraciously, became an assistant instructor in Hebrew and, for a time taught himself to read a new language every month; by 1836, he claimed a reading knowledge of “twenty tongues.” Among his many extracurricular activities, he edited the Scriptural Interpreter, a student journal of biblical criticism, and published many small articles in the Unitarian weekly, the Christian Register.

Parker completed his Divinity School courses in the spring of 1836. In April 1837, he married Lydia Cabot. That June, Parker was ordained minister of the West Roxbury Unitarian church, which had only 60 adult members. Parker took this small settlement at the urging of his wife’s family, who lived nearby.

Parker found he could fulfill all his duties to his little parish and still devote most of his energy to studying and to building his literary and scholarly reputation. He read thousands of books, wrote scores of short pieces for the Register, as well as major scholarly articles for various journals, including the principal Unitarian periodical, the Christian Examiner. Meanwhile, he won notice around Boston for his intelligent, eloquent, heartfelt sermons. His theology, however, made him an increasingly controversial figure.

Unitarians generally adhered to a theological system that historians have identified as “supernatural rationalism.” According to this view, “unassisted” human reason could determine certain religious truths, such as the existence of God; these truths collectively made up “natural religion.” Natural religion had to supplemented, however, by “revealed religion”; certain essential religious truths, such as that Christ plays a mediatorial role in salvation, could be discovered only through the miraculous revelation given in the Bible. Those who denied that Christianity was a miraculous revelation were “infidels” or “deists,” unworthy of Christian fellowship. Parker during the 1830s came to deny Christianity was a miraculous revelation, but insisted he was still Christian and worthy of fellowship.

He originally grounded his faith in the Bible, which he believed contained a miraculous revelation. In 1832, he wrote “A History of the Jews,” meant to be a Sunday school textbook (it was never published), in which he defended the miracle stories of the Old Testament as literally factual. His views began to change when Convers Francis, the Unitarian minister in Watertown, introduced him to the new field of historical biblical criticism, then being developed in Germany.

By 1834, Parker was interpreting some Old Testament miracle stories naturalistically. In 1836, in an article for the Interpreter, he denied the traditional view—accepted by most Unitarians—that the prophet Isaiah had predicted the coming of Christ. He also in 1836 began the huge project, which took him seven years to complete, of producing an English language edition (expanded and revised) of a seminal work of German biblical criticism, W.M.L. De Wette’s Critical and Historical Introduction to the Old Testament (1817). De Wette argued that the Old Testament miracles were best not accepted as facts, nor dismissed as legends, but appreciated as “myths”—that is, poetic expressions of ancient Jewish piety with profound symbolic meaning.

Meanwhile, the German critic D.F. Strauss made the same claim regarding New Testament miracles in his explosively controversial Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (1835). Parker wrote a long, generally sympathetic review of Strauss’s book for the Examiner in 1840. By that point, Parker had come to doubt the factuality of all miracle stories and to see the Bible as full of contradictions and mistakes.

Parker put his faith on a new foundation by developing his own theory of divine inspiration. He now held that God was “immanent in matter and man.” The laws of the human spirit were analogous to the laws of matter; both were aspects of God and so eternal and immutable. Matter must obey its law, but God had given humans the freedom to disobey spiritual laws. Disobedience constituted sin. Obedience constituted divine inspiration. The more closely one obeyed spiritual laws, the more one took on the qualities of God—that is, the more one became True, Moral, Loving, and Faithful—and the more divinely inspired one became. Divine inspiration was natural and universal, and the human race, as it progressed from “savagery” to “civilization,” grew ever more inspired.

Most Unitarians believed Jesus had been inspired in a miraculous manner to give an authoritative revelation. Parker now believed Jesus had been inspired in the same manner as everyone else, by being true to the spiritual laws. Parker still honored Jesus, however, as the most divinely inspired person in history; Parker thought Jesus had preached the “Absolute Religion.” The authority of Jesus’ revelation, however, was only of that truth. Meanwhile, Parker held that many modern people were more divinely inspired than many of the Biblical writers, who lived in more primitive times.

Parker’s ideas were consonant with those of the Transcendentalist movement, which emerged among younger Unitarians in the mid-1830s. Parker attended meetings of the so-called “Transcendentalist Club” and contributed many articles and reviews to the most important Transcendentalist periodical, The Dial (1840-1844). In 1838, he enthusiastically listened to the Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson deliver the Divinity School Address. Its prophetic tone inspired Parker to begin preaching on church and social reform.

Meanwhile, Emerson’s eloquent attack on miracles in his Address sparked a heated pamphlet controversy. Andrews Norton made the supernatural rationalist case that to deny the Christian miracles was “infidelity,” while George Ripley defended Transcendentalism. When Parker concluded the two antagonists had become preoccupied with scholarly matters that did not concern ordinary Unitarian believers, he tried to redirect the debate. He published a pamphlet, The Previous Question (1840), which he wrote in the voice of a fictitious ordinary Unitarian believer named “Levi Blodgett.” Here he vigorously laid out the Transcendentalist position on inspiration, miracles, and religious authority.

Parker emerged as a major Transcendentalist spokesman in May 1841, when he delivered A Discourse on the Transient and Permanent in Christianity at an ordination in South Boston. Parker intended the main point of the sermon to be that Jesus preached the Absolute Religion. What made the strongest impression on Parker’s audience, however, was his vehement denial of the factuality of Biblical miracles and of the miraculous authority of both the Bible and Jesus. Particularly outraged were three Trinitarian guests in the audience. They published an attack on the sermon in the newspapers and demanded to know if Unitarians considered Parker a Christian minister. During the resulting uproar, most Unitarian ministers, and a large portion of the Unitarian lay public, concluded that Parker’s theology was not Christian.

Parker found himself denied access to Unitarian pulpits and shut out of the Register and the Examiner. He feared his ministerial career was over. The controversy did in fact cost him friendships and forced him to abandon his early dream of becoming accepted as a member of the Boston elite. Even his wife’s family, he later wrote, treated him as if he had committed a crime.

His West Roxbury congregation stood by him, however, and the outcry against him made him famous. In the fall of 1841, audiences flocked to hear him deliver a course of lectures that he published in revised form the following spring as A Discourse of Matters Pertaining to Religion. In this Transcendentalist manifesto, Parker systematically laid out his ideas about inspiration, Jesus, the Bible, and the church. Unitarian critics denounced the book as “deistical” and impious.

In the fall of 1842, Parker caused further controversy by defending John Pierpont, minister of the (Unitarian) Hollis Street Church in Boston. Pierpont’s support for temperance legislation had divided his congregation. A hostile minority, who controlled the church finances, had tried to fire him. In 1841, an ecclesiastical council of leading Unitarians had attempted to resolve this dispute, without success. In an article for the October 1842 Dial, Parker accused the Hollis Street Council of having been secretly hostile to Pierpont because he was a reformer. Parker’s accusation delighted Pierpont’s friends but insulted Parker’s Boston colleagues.

Parker’s conflict grew particularly intense with his colleagues in the (all Unitarian) Boston Association of Congregational Ministers. The Association had a confrontational meeting with him in January 1843 in which they tried to persuade him to resign his membership. He refused.

In the fall of 1843, Parker took a European sabbatical with Lydia. His first exposure to great inequalities of wealth and to political despotism led him to think increasingly about democracy, democratic society, and democratic culture.

Meanwhile, theological controversy engulfed him again. In November 1844, John Sargent conducted a pulpit exchange with Parker. Sargent pastored a Unitarian chapel for the poor in Boston, one of two sponsored by the Benevolent Fraternity of Churches. The Board of the Fraternity instructed Sargent not to exchange with Parker again, because Parker’s theology was offensive. Sargent resigned his position in protest, accusing the Board of violating Unitarian principles.

In December, Parker gave a Thursday Lecture at the First Church, Boston. The traditional weekly “Thursday Lecture” (actually a sermon) was sponsored by the Boston Association; every member preached one when his turn came in rotation. Parker’s sermon on “The Relation of Jesus to His Age and the Ages” reaffirmed his naturalistic Christology. The Boston Association responded by debating whether to expel him. In the end they decided only to turn administration of the Thursday Lecture over to the First Church, a move that in effect prevented Parker from preaching it again.

In January 1845, James Freeman Clarke, pastor of the (Unitarian) Church of the Disciples in Boston, who disliked Parker’s theology but feared that liberal Christians were becoming “exclusive,” conducted a pulpit exchange of his own with Parker. Fourteen leading families in his congregation resigned in protest and started their own society.

These events prompted extensive, public Unitarian soul-searching over whether Unitarians had an implicit creed, whether they ought to have an explicit one, and whether they owed Parker ministerial fellowship. Parker presented his own position in A Friendly Letter to the Boston Association (1845), in which he maintained that Unitarians had no grounds to exclude him.

In January 1845, Parker accepted the invitation of some supporters to preach regularly in Boston. They rented the Melodeon Theater, and he delivered his first sermon there in February, to a large audience. Over the following year, he preached in the morning at the Melodeon and in the afternoon at West Roxbury. In December 1845, Parker’s supporters organized the 28th Congregational Society of Boston. He was installed as its minister in January 1846, his isolation from his colleagues symbolized by his preaching his own installation sermon (The True Idea of a Christian Church). He resigned his West Roxbury pulpit the following month.

The core of Parker’s society consisted of about 300 people, most of them former parishioners of John Sargent and John Pierpont (who left Boston in 1845); this group financed the society and managed its affairs. Attendance at Parker’s services grew from 1000 in 1846 to 2000 in 1852, prompting the congregation to move from the Melodeon to the more spacious Boston Music Hall. Even larger audiences turned out whenever Parker preached on some significant public issue or political event. Those who worshipped at the Melodeon or Music Hall included William Lloyd Garrison, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Julia Ward Howe, Samuel Gridley Howe, William C. Nell, and Louisa May Alcott (who gave favorable, thinly fictionalized account of her experience in her novel Work).

The 28th Congregational Society was not generally considered a Unitarian organization. It was called a “free church” and its members were sometimes called “Parkerites.” Parker’s personal ties to Unitarianism attenuated. Unitarian ministers did not exchange pulpits with him, and Unitarian publications either ignored or criticized him. He lost his membership in the Boston Association when he resigned his West Roxbury pulpit and was never re-admitted. He attended the annual meetings of the American Unitarian Association (AUA), but less out of sympathy with the organization than to show he had right to be there. In 1853, when the leaders of the AUA published a Christian-sounding “proclamation of Unitarian views,” Parker strongly critiqued it in A Friendly Letter to the Executive Committee of the American Unitarian Association.

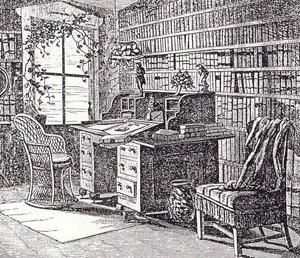

With Parker’s move to Boston, he became a nationally prominent intellectual. He lectured all over the North, published books and sermons continuously, edited the Massachusetts Quarterly Review (1848-1851), corresponded extensively, and collected a personal library of 13,000 volumes, every one of which he was reputed to have read. His thought developed in new directions.

In theology, Parker’s ongoing biblical research persuaded him that Jesus had not preached the Absolute Religion, but had made serious theological mistakes. His new view was reflected in the revised, 4th edition of the Discourse of Matters Pertaining to Religion (1854). Meanwhile, the rise of philosophical atheism, such as that propounded by the German thinker L. Feuerbach, prompted Parker to move from emphasizing human religious potential to emphasizing the reality of God. The shift can be seen in his book on Theism, Atheism, and the Popular Theology (1853). At the same time, he criticized evangelical revivalism, which he argued promoted degrading ideas of God and human nature. In 1858, he attacked revivals in two sermons that became national best-sellers, A False and True Revival of Religion and The Revival of Religion Which We Need.

Parker developed a new, sociological understanding of society. He filled his sermons and lectures with statistics, talked about social “classes,” and became preoccupied with ethnology and “romantic” racial theory. He asserted that the Anglo-Saxon “race” was “more progressive” than all others, European or non-European, and made many condescending and disparaging comments about the potential of “Africans” for progress. Despite such views, he favored the racial integration of Boston schools and churches, and he became a leading abolitionist.

He linked his politics to a vision, which he began to develop after his European trip, of America becoming “industrial democracy.” Its government would be a true democracy, as opposed to an aristocracy or a monarchy, when it was “of all the people, by all the people, for all the people” (a concept that influenced Abraham Lincoln). By this phrase, Parker meant a government that was an organic expression of the whole people’s mind, conscience, and piety, that was controlled by no individual or class, and that acted on behalf of all, and not on behalf of an individual or class. Meanwhile, the American social order would be “industrial,” as opposed to “feudal,” when it valued people for their work and character, rather than their wealth and social position. An industrial democracy would promote the spiritual perfection of each individual and therefore would be the most religious possible form of society.

Parker believed that the United States came closer to being an industrial democracy than any other society in the world, but fell far short of the ideal. To bring it closer, he developed a comprehensive program of cultural, social, and political reform.

He criticized what he saw as the “aristocratic” atavisms in American literature and education, and championed better schools and universal education. He supported efforts to alleviate urban poverty, and urged that the criminal justice system reform criminals, not punish them. He advocated for the end of the “degradation of women” and endorsed women’s suffrage (notably in his sermon, On the Public Function of Woman [1853]).

Parker saw slavery as the greatest obstacle to achieving industrial democracy. He denounced the Mexican War (1846-1848) as an attempt to expand slavery and led Boston opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The act established a federal bureaucracy to catch slaves who had escaped to the free states. Most Boston Unitarian ministers either refused to oppose the legislation, or publicly supported it as a constitutional obligation and as a politically necessary concession to the South that would “save the Union” and “settle” the slavery issue. Some argued that catching fugitive slaves was sanctioned by Scripture. Parker pronounced the act a violation of Christian ideals and a threat to free institutions. In his Sermon of Conscience (1850), he openly called for it to be defied.

Parker served as the abolitionists’ Minister at Large to fugitive slaves in Boston. He chaired the executive committee of the Vigilance Committee, the principal Boston organization providing fugitives with material aid, legal assistance, and help in eluding capture. In 1850, when a fugitive in his congregation, Ellen Craft, was threatened with arrest, he hid her in his house until arrangements could be made to send her to Canada. In 1854, his agitation on behalf of another fugitive, Anthony Burns, led to Parker’s indictment by a federal grand jury. He was charged with obstructing a federal marshal. Popular opinion was so much on his side, however, that prosecuting him became a political impossibility. In 1855, the case was dismissed on a technicality.

Parker grew convinced that there could be no wholly political solution to the slavery crisis. During the proto-civil war in Kansas territory, he raised money to buy weapons for the free state militias, and later became a member of the secret committee that helped finance and arm John Brown’s failed attempt, in October 1859, to start a slave insurrection in Virginia. When Brown was arrested, Parker wrote a public letter defending Brown’s actions and the right of slaves to kill their masters (John Brown’s Expedition Reviewed).

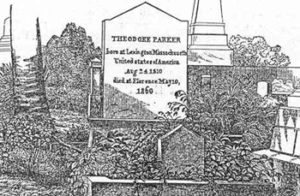

Parker’s health began to fail in 1857. In January 1859, he suffered a physical collapse, brought about by tuberculosis, which ended his preaching career. In February, he left wintry Boston with his wife and others for the warmth of the Caribbean. While on the island of Santa Cruz in March and April, he wrote a long, autobiographical letter to his congregation that was also a confession of faith. It soon was published as Theodore Parker’s Experience as a Minister. Parker then traveled to England, Switzerland, and Italy. His condition worsened in the winter of 1859, and he died on 10 May 1860, in Florence.

The Boston Unitarian leadership remained hostile to the end. In 1859, with Parker sick, the annual meeting of Harvard Divinity School alumni refused to allow a vote on a proposed resolution of sympathy. But many younger Unitarian ministers admired him for his assault on traditional theology, his fight for a free faith and a free pulpit, and his example of public engagement. When they took over the leadership of Unitarianism, in the late 19th century, they made Parker a canonical figure—the model of a prophetic minister in the American Unitarian tradition.

Yet Parker’s actual ideas have been half forgotten, and some criticize him for having been unnecessarily divisive and confrontational. He also is charged with having been an inadequate churchman. The 28th Congregational Society commonly is believed to have been a “one-man show” that collapsed after his death. In fact, although the crowds departed the Society after 1860, the core membership remained active. They appointed a number of successors to Parker, the most well known being David A. Wasson; they built their own meeting house, the Parker Memorial Building, in 1873; and they continued to offer services until 1889, when they turned over their assets (ironically enough, considering the dispute over Parker’s exchange with John Sargent in 1844) to the Benevolent Fraternity of Churches.

The Andover-Harvard Theological Library holds more than 700 of Parker’s manuscript sermons, four volumes of his journal, many notebooks, manuscripts for several of his books, including three drafts of A Discourse of Matters Pertaining to Religion, and many letters. The Massachusetts Historical Society holds the largest collection of letters to and from Parker (mostly in copied form), two more volumes of his journal, and notebooks. The Boston Public Library holds Parker’s Sermon Record Book, some important manuscripts, including “The History of the Jews” and the Experience as a Minister, and many letters, notebooks, and scrapbooks; Parker also bequeathed his personal library to the BPL, and his original books may be examined there. Significant collections of Parker letters can be found as well at the Houghton Library, Harvard University; the Library of Congress; the Huntington Library; and the State Archives of Neuchâtel, Switzerland; many other libraries have smaller holdings. The most thorough bibliography of Parker’s publications to 1846 appears in Dean Grodzins, American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism (2002); see also Joel Myerson, Theodore Parker: A Descriptive Bibliography (1981). There are two editions of Parker’s writings, The Collected Works of Theodore Parker, 14 vols. (1863-1872), and The Works of Theodore Parker, Centennial Edition, 15 vols. (1907-1913); these collections are difficult to dispense with, although neither contains wholly reliable texts.

The five principal biographies of Parker are John Weiss, Life and Correspondence of Theodore Parker (2 vols; 1864), Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Theodore Parker: A Biography (1874), John White Chadwick, Theodore Parker: Preacher and Reformer (1900), Henry Steele Commager, Theodore Parker: Yankee Crusader (1936), and Dean Grodzins, American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism (2002). This last, which significantly revises earlier accounts of Parker’s life to 1846, should be supplemented by two articles which provide a revised account of his later life: Grodzins, “Theodore Parker,” in Wesley T. Mott, ed., Dictionary of Literary Biography 235: American Renaissance in New England (2001) and Grodzins, “Theodore Parker and the 28th Congregational Society: The Reform Church and the Spirituality of Reformers in Boston, 1845-1859,” in Charles Capper and Conrad E. Wright, eds., Transient and Permanent: The Transcendentalist Movement and Its Contexts (1999). The latter article discusses Parker’s theory and practice of church life.

Brief but informed overviews of Parker’s thought, from different perspectives, appear in Daniel Aaron, Men of Good Hope: A Story of American Progressives (1951), chap. 2, which emphasizes his reform ideas, and Lewis Perry, Boats Against the Current: American Culture Between Revolution and Modernity (1993), chap. 22, which treats both his politics and theology. The only monograph assessment of Parker’s theology published after 1900 is John Dirks, The Critical Theology of Theodore Parker (1948); his conclusion, that Parker was really not a Transcendentalist, suggests only that his definition of Transcendentalism is inadequate. Commager, meanwhile, in an important article (“The Dilemma of Theodore Parker,” New England Quarterly [June 1933]), and in his biography of Parker, argues that Parker’s interest in empiricism contradicted his Transcendentalism. Yet Parker saw no contradiction; he believed that God was “immanent in matter and man,” so empirical study and intuition should lead to the same conclusions, and in fact he believed each complemented the other. See also the comments on Parker’s theology in William Hutchison, The Transcendentalist Ministers: Church Reform in the New England Renaissance (1959), chap. 4. Parker’s biblical criticism is discussed in Dirks and placed in wider context by Jerry Wayne Brown, The Rise of Biblical Criticism in America, 1800-1870: The New England Scholars (1969), chap. 10; Brown fails, however, to distinguish between the first and fourth editions of Parker’s Discourse of Religion, and therefore misrepresents Parker’s early position on Jesus.

Parker’s racial views have never received adequate treatment, but see Michael Fellman, “Theodore Parker and the Abolitionist Role in the 1850s,” Journal of American History (December 1974) and Paul A. Teed, “Racial Nationalism and its Challengers: Theodore Parker, John Rock, and the Antislavery Movement,” Civil War History, (June 1995). George M. Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914 (1971), provides a description of the romantic racialist position Parker espoused; Fredrickson points out the “obvious need for a further and more detailed explanation of the paradox presented by Parker’s tendency to be an extreme racist when he discussed black capabilities . . . and a militant egalitarian on questions of racial policy.”

Article by Dean Grodzins

Posted September 9, 2002