Michael Servetus (c.1506-October 27, 1553), a Spaniard martyred in the Reformation for his criticism of the doctrine of the trinity and his opposition to infant baptism, has often been considered an early unitarian. Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox trinitarian. Still, aspects of his thinking—his critique of existing trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts—did influence those who later inspired or founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. Public criticism of those responsible for his execution, the Reform Protestants in Geneva and their pastor, John Calvin, moreover, stirred proto-unitarians and other groups on the radical left-wing of the Reformation to develop and later institutionalize their own heretical views. Widespread aversion to Servetus’s death has been taken as signaling the birth in Europe of the idea of religious tolerance, a principle now more important to modern Unitarian Universalists than antitrinitarianism. Servetus is also celebrated as a pioneering physician. He was the first European to publish a description of the blood’s circulation through the lungs.

Michael Servetus (c.1506-October 27, 1553), a Spaniard martyred in the Reformation for his criticism of the doctrine of the trinity and his opposition to infant baptism, has often been considered an early unitarian. Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox trinitarian. Still, aspects of his thinking—his critique of existing trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts—did influence those who later inspired or founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. Public criticism of those responsible for his execution, the Reform Protestants in Geneva and their pastor, John Calvin, moreover, stirred proto-unitarians and other groups on the radical left-wing of the Reformation to develop and later institutionalize their own heretical views. Widespread aversion to Servetus’s death has been taken as signaling the birth in Europe of the idea of religious tolerance, a principle now more important to modern Unitarian Universalists than antitrinitarianism. Servetus is also celebrated as a pioneering physician. He was the first European to publish a description of the blood’s circulation through the lungs.

The date of Servetus’s birth is unknown. The most widely-accepted date, 1511, is based upon his testimony to the French inquisition. In this situation he had every reason to conceal his true identity. A better case may be made for an earlier date, based upon the testimonies those who knew him when he was a young man and who had no motivation to dissemble. Moreover, the story of his education, his first employment, and the composition of his first writing makes more sense when a date of birth around 1506 is accepted.

The first of three sons of Antón Serveto and Catalina Conessa, Miguel was born and grew up in Villanueva, Aragon, sixty miles east of Zaragoza. He must have shown precocious talent, for instead of being prepared to inherit the business of his notary father, he was sent to study law in Toulouse, France. Upon his return, around 1525, he entered the service of Juan de Quintana, a scholarly Augustinian monk, who was a native of a neighboring town. Quintana served as preacher and chaplain at the court of Charles I, king of Castille and Aragon, who, as Charles V, was also ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

From 1522 until 1529 King Charles, who was born and had grown up in the Burgundian Netherlands, traveled throughout Spain becoming acquainted with his new kingdom. Servetus must have spent much of his time in attendance at this peripatetic court. Quintana was given three important commissions during this time, each one of which helped to shape Servetus’s emerging religious views: 1) to help prosecute the Alumbrados (the illumined ones), a mystical and reformist sect who exhibited a dangerous independence from church authority, 1525-29; 2) to study the situation of the Moriscos (Muslims forcibly converted to Christianity) of Granada, 1526; and 3) to help pass judgment on the orthodoxy of the writings of Desiderius Erasmus at a conference in Valladolid, 1527. Servetus’s heretical spirit, his reshaping of Christianity to make it more attractive to Muslims, and his critical and humanistic approach to the Bible all originated in his observation of and reaction to these three investigations. Around 1527 Servetus felt himself “driven by a divine impulse to write.” Accordingly, in secret, he began to compose a treatise which he strove to outline a Spanish-inflected reformation.

In 1529 Servetus accompanied his employer, Quintana, who was by this time the royal confessor, and the imperial party as they traveled to the coronation of Charles V in Bologna, Italy. In Italy Servetus was horrified by riches of the church, the worldliness of the priesthood, and the adoration accorded the Pope. He nevertheless remained with Quintana as Charles went on to the Diet of Augsburg, 1530, to meet with Protestant leaders and to try to find a formula to reunite Christianity. Some time during that year Servetus dropped out of the Emperor’s entourage and made his way to the Swiss city of Basel to join the Protestants. He stayed for months in the household of Oecolampadius, the local pastor and Reform leader.

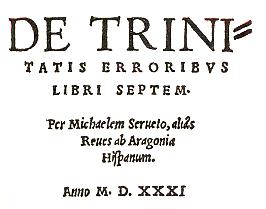

Having worn out his welcome there with constant theological dispute, Servetus moved to more tolerant Strasburg. There, in 1531, he published the book upon which he had been working for four years, De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). If Servetus hoped this work would persuade the new Protestant establishment to re-think orthodox trinitarian doctrine, as traditionally interpreted by the later Church Fathers and the mediaeval Scholastics, and to replace it with his own formulation, he was quickly disappointed. Although Protestants admired some aspects of Servetus’s thought, they deplored many others. Moreover, they were especially defensive concerning their trinitarian orthodoxy, having no desire to call upon themselves still more Roman Catholic denunciation. The Lutheran reformer Melanchthon, commenting on De Trinitatis Erroribus, lamented, “As for the Trinity you know I have always feared this would break out some day. Good God, what tragedies this question will excite among those who come after us!”

Having worn out his welcome there with constant theological dispute, Servetus moved to more tolerant Strasburg. There, in 1531, he published the book upon which he had been working for four years, De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). If Servetus hoped this work would persuade the new Protestant establishment to re-think orthodox trinitarian doctrine, as traditionally interpreted by the later Church Fathers and the mediaeval Scholastics, and to replace it with his own formulation, he was quickly disappointed. Although Protestants admired some aspects of Servetus’s thought, they deplored many others. Moreover, they were especially defensive concerning their trinitarian orthodoxy, having no desire to call upon themselves still more Roman Catholic denunciation. The Lutheran reformer Melanchthon, commenting on De Trinitatis Erroribus, lamented, “As for the Trinity you know I have always feared this would break out some day. Good God, what tragedies this question will excite among those who come after us!”

Servetus tried the effect of a slightly more conciliatory volume, Dialogorum de Trinitate (Dialogues on the Trinity), published the following year. But in it he neither conceded anything important to his system, nor even softened his rhetoric. His second volume was neither intended nor received as a recantation. His books were confiscated, and he was warned out of several Protestant towns. Meanwhile, in 1532, the Supreme Council of the Inquisition in Spain began proceedings to summon him, or to apprehend him, if he would not voluntarily appear before the tribunal. His youngest brother, Juan, a priest, was sent to persuade him to return to Spain for questioning. Servetus was terrified. He later wrote of this period, “I was hunted far and wide that I might be seized and put to death.” He fled to Paris and surfaced there with a new name, Michel de Villeneuve.

As “Villeneuve” Servetus studied mathematics and medicine at colleges in Paris, then a center of religious ferment. Nicholas Cop, Rector of the University, was forced to flee the city after an inaugural address deemed too Protestant. A young student of Servetus’s acquaintance, John Calvin, who may have written the address, had also to leave town and to go into hiding. Sometime during the next year Calvin risked his life to return to Paris that he might meet Servetus and respond to his theological challenges. Servetus, perhaps afraid of being seen with a fugitive, did not show up. Driven to witness for his religious cause, he yet felt unready to be its effective champion. “This is the reason I postponed my task,” he recalled, “and because of the persecution which so loomed over me, that, like Jonah, I wanted instead to take flight upon the sea or escape to some newly discovered island.”

For many years Servetus supported himself in France by working as an editor, first for the firm of Trechsel in Lyons and later also for Jean Frellon. For Trechsel, Servetus edited, and also added a few new notes to, two editions of Ptolemy’s Geography, 1535 and 1541. With this work to his credit, he set himself up as an expert on geography and supplemented his income by giving lectures on the subject. He next prepared an edition of the Santes Pagnini’s Bible, completed in seven volumes in 1545. His introduction and notes anticipate modern biblical criticism and show an advance in sophistication beyond that of his early theological writing.

Inspired by some of the medical works published by Trechsel, Servetus decided to return to the study of medicine. From 1536-38 he was a medical student at the University of Paris. He followed the celebrated anatomist Andreas Vesalius as assistant to Hans Gunther in dissection. Gunther wrote that “Michael Villonovanus” had a knowledge of Galen “second to none.” Servetus soon came to differ from Galen in the matter of pulmonary circulation. Galen had supposed aeration of the blood took place in the heart and assigned the lungs a fairly minor function. Servetus concluded that transformation of the blood, accomplished by the release of waste gases and the infusion of air, occurred in the lungs. However, because he only expressed the new knowledge as a metaphor in his proscribed theological writing, it had no influence on William Harvey’s description of circulation in the next century.

In 1538 Servetus, as Villeneuve, got into trouble with the faculty of medicine, the Parlement of Paris, and the Inquisition for mixing astrology with medicine. Although he was acquitted by the Inquisition, the Parlement ruled that his published self-defense was to be confiscated and he was to desist from the practice of astrology. Servetus left Paris shortly thereafter, perhaps without a degree, to practice medicine in the area of Lyons. Around 1540 he became the personal physician of Pierre Palmier, Archbishop of Vienne.

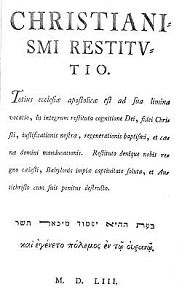

During his twelve-year residence in Vienne, living as the inoffensive Doctor of Medicine, Michel de Villeneuve, Servetus was busy in his spare time preparing a major theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity). He also initiated, in 1546, a fateful secret correspondence with his old acquaintance, John Calvin. By this time Calvin, author of Institutio Christianae Religionis (Institutions of the Christian Religion), 1536, and pastor and chief reformer of Geneva, was the most prestigious figure in the Reform branch of Protestantism.

Calvin’s theology had included little mention of the trinitarian nature of the godhead until, in 1537, another reformer, Pierre Caroli, accused him of being an Arian. Although cleared by a synod at Lausanne, Calvin was soon after forced to leave Geneva for several years. He was thereafter on his guard and determined to deal severely with any deviations in this area of orthodoxy. The subject, associated with unpleasant memories, was distasteful to him. Servetus, surely aware of Calvin’s previous lack of clarity on the subject, bombarded him with letters insisting on unorthodox conceptions even more radical than those he had presented in De Trinitatis erroribus. Calvin replied with increasing impatience and asperity. Servetus sent Calvin a manuscript of his yet unpublished Restitutio. Calvin reciprocated by sending a copy of the Institutio. Servetus returned Institutio with abusive annotations but Calvin refused to return Servetus’s manuscript. On the day Calvin broke off the correspondence, he wrote to his colleague, Guillaume Farel, that should Servetus ever come to Geneva, “if my authority is of any avail I will not suffer him to get out alive.”

When Servetus finally published Christianismi Restitutio in early 1553 he sent an advance copy to Geneva. The printed text included thirty of his letters to Calvin. Soon afterward, at Calvin’s behest, the true identity of “Villeneuve” was betrayed to the French Inquisition in Vienne. After his arrest and interrogation Servetus managed to escape from the prison. On his way, perhaps, to northern Italy or to southeastern Switzerland, where he may have hoped that there were people receptive to his writings, he crossed the border into Geneva. Recognized at a church service, he was arrested and tried for heresy by Protestant authorities.

When Servetus finally published Christianismi Restitutio in early 1553 he sent an advance copy to Geneva. The printed text included thirty of his letters to Calvin. Soon afterward, at Calvin’s behest, the true identity of “Villeneuve” was betrayed to the French Inquisition in Vienne. After his arrest and interrogation Servetus managed to escape from the prison. On his way, perhaps, to northern Italy or to southeastern Switzerland, where he may have hoped that there were people receptive to his writings, he crossed the border into Geneva. Recognized at a church service, he was arrested and tried for heresy by Protestant authorities.

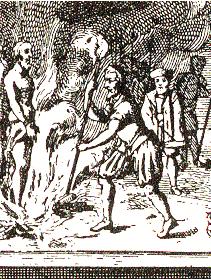

The secular officials were unable to establish that Servetus was an immoral disturber of the public peace. Nevertheless, he made damaging theological statements in the course of a written debate with Calvin. The Council of Geneva, after receiving the advice of churches in four other Swiss cities, convicted Servetus of antitrinitarianism and opposition to child baptism. Calvin asked that Servetus be mercifully beheaded. The Council insisted he should be burned at the stake.

Spectators were impressed by the tenacity of Servetus’s faith. Perishing in the flames, he is said to have cried out, “O Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have pity on me!” Farel, who witnessed the execution, observed that Servetus, defiant to the last, might have been saved had he but called upon “Jesus, the Eternal Son.” A few months later Servetus was again executed, this time in effigy, by the Inquisition in France.

Spectators were impressed by the tenacity of Servetus’s faith. Perishing in the flames, he is said to have cried out, “O Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have pity on me!” Farel, who witnessed the execution, observed that Servetus, defiant to the last, might have been saved had he but called upon “Jesus, the Eternal Son.” A few months later Servetus was again executed, this time in effigy, by the Inquisition in France.

Many Protestants approved the Genevan sentence. Others, especially in Basel, were not so sure that heretics ought to be put to death. In answer to critics, Calvin quickly put together and published, in 1554, a justification, Defensio orthodoxae fidei, contra prodigiosos errores Michaelis Serveti Hispani (Defense of Orthodox Faith against the Monstrous Errors of the Spaniard Michael Servetus). He argued that to spare Servetus would have been to endanger the souls of many. In the same year Calvin was answered by Sebastian Castellio, in Contra libellum Calvini (Against Calvin’s Booklet). Castellio declared that “to kill a man is not to protect a doctrine; it is but to kill a man. When the Genevans killed Servetus, they did not defend a doctrine; they but killed a man.” He said that “if Servetus had wished to kill Calvin, the Magistrate would properly have defended Calvin. But when Servetus fought with reasons and writings, he should have been repulsed by reasons and writings.”

Nearly all copies of Servetus’s magnum opus, Christianismi Restitutio, were destroyed by the authorities. Only three have survived. Its peculiar, unorthodox trinitarian theology, which made Servetus a hunted man in nearly every country in Western Europe, cannot be summarized simply. Unitarian scholar Earl Morse Wilbur, who translated De Trinitatis Erroribus, found the Restitutio less to his liking and passed over coming to terms with it. John Godbey, a Unitarian Universalist scholar of the Radical Reformation, wrote that “most persons lack sufficient understanding of his views to make defensible statements about him.”

Servetus had no use for the doctrine of original sin and the entire theory of salvation based upon it, including the doctrines of Christ’s dual nature and the vicarious atonement effected by his death. He believed Jesus had but one nature, at once fully human and divine, and that Jesus was not another being of the godhead separate from the Father, but God come to earth.

Other human beings, touched by Christian grace, could overcome sin and themselves become progressively divine. He thought of the trinity as manifesting an “economy” of the forms of activity which God could bring into play. Christ, the Son of God, did not always exist. Once but a shadow, he had been brought to substantial existence when God needed to exercise that form of activity. In some future time he would no longer be a distinct mode of divine expression. Servetus called the crude and popular conception of the trinity, considerably less subtle than his own, “a three-headed Cerberus.” (In Greek mythology Cerberus is a three-headed dog-like creature of the underworld.) Servetus did not believe people are totally depraved, as Calvin’s theology supposed. He thought all people, even non-Christians, susceptible to or capable of improvement and justification. He did not restrict the benefits of faith to a few recipients of God’s parsimonious dispensation of grace, as did Calvin’s doctrine of the elect. Rather, grace abounds and human beings need only the intelligence and free will, which all human beings possess, to grasp it. Nor did Servetus describe, as did Calvin, an infinite chasm between the divine and mortal worlds. He conceived the divine and material realms to be a continuum of more and less divine entities. He held that God was present in and constitutive of all creation. This feature of Servetus’s theology was especially obnoxious to Calvin. At the Geneva trial he asked Servetus, “What, wretch! If one stamps the floor would one say that one stamped on your God?”

Calvin asked if the devil was part of God. Servetus laughed and replied, “Can you doubt it? This is my fundamental principle that all things are a part and portion of God and the nature of things is the substantial spirit of God.” The devil was an important factor in Servetian theology. Servetus was a dualist. He thought God and the devil were engaged in a great cosmic battle. The fate of humanity was just a small skirmish in salvation history. He charged orthodox trinitarians with creating their doctrine of the trinity, not to describe God, but to puff themselves up as central to God’s concern. Because they defined God to suit their own purposes, he called them atheists.

Servetus’s demonology included the notion that the devil had created the papacy as an effective countermeasure to Christ’s coming to earth. Through the popes the devil had taken over the church. Infant baptism was a diabolic rite, instituted by Satan, who in ancient days had presided over pagan infant sacrifices. He calculated that the Archangel Michael would soon come to bring deliverance and the end of the world, probably in 1585.

Dualism, millenarianism, and modal trinitarianism are not elements of the Servetian legacy which Unitarian Universalists today celebrate. Nor were they affirmed by those of Servetus’s contemporaries most in sympathy with his thought, the Italians—later known as Socinians—who developed and spread an early form of Unitarianism in Poland. They took heart from some aspects of Servetus’s doctrine and ignored or rejected the rest. Nevertheless, although Michael Servetus has now no real disciples and in the years following his death never had more than a handful, his pioneering life and the tragedy of his death did inaugurate, in a sense, the history of modern liberal religion.

It is one of the ironies of history that all the modern Unitarian churches and movements hold the memory of Michael Servetus in special honour—for every one of them developed historically and organically out of the Reformed tradition of John Calvin.

The complete works of Servetus, the Obras Completas, have been issued in Spanish and Latin in six volumes, edited by Angel Alcala (2003-2007). Many of Servetus’s works are now available in English: The Two Treatises of Servetus on the Trinity, translated by Earl Morse Wilbur (1932); Michael Servetus, A Translation of His Geographical, Medical, and Astrological Writings, translated by Charles Donald O’Malley (1953); and The Restoration of Christianity, 4 vols., translated by Christopher Hoffman and Marian Hillar (2007-10). English translations of some of Servetus’s Bible annotations are included in Louis Israel Newman Jewish Influence on Christian Reform Movements (1925). Declaratio, a manuscript from the 1550s once thought to be a work of Servetus, has now been shown to be by Matteo Gribaldi. It can be found, in Latin and English, in Matteo Gribaldi, Declaratio: Michael Servetus’s Revelation of Jesus Christ, the Son of God (2010), ed. and trans. by Peter Zerner and Peter Hughes. A bibliography of Servetus’s works put together by Madeleine Stanton is included in in John F. Fulton, Michael Servetus: Humanist and Martyr (1953). Information on the trials of Servetus can be found in Calvin’s Defensio (French, Déclaration), which is not yet available in English. Also in French is Le Procès de Servet (The Trial of Servetus), printed (with Defensio) as an appendix to Volume 8 of Calvin’s Works (Calvini Opera). This has also been made available in Spanish in volume 1 of Obras Completas. The trial before the Inquisition in France is treated in Pierre Cavard, Le Procés de Michel Servet à Vienne (1953). The Register of the Company of Pastors of Geneva in the Time of Calvin, translated by Philip Edgecumbe Hughes (1966) contains much primary documentation of the Servetus affair.

John Calvin did not treat the trinity very extensively in the first edition of Institutio Christianae Religionis (1536). He expanded greatly the section on the trinity in the edition published after the death of Servetus (1559), available as two volumes, 20-21, of the Library of Christian Classics, translated by John T. McNeill (1960). In this later version are many references to Servetus. A good explanation of Calvin’s theology is found in Wilhelm Niesel, The Theology of Calvin (1956). Calvin’s letter to Farel threatening Servetus is in Letters of John Calvin, volume 2, edited by Jules Bonnett and translated by David Constable (1857). Correspondence related to Servetus can be found in Calvin’s Works, vols. 12-14 and 20. Castellio’s reply to Calvin has been translated into French by Etienne Barilier as Contre la libelle de Calvin (1998). Another relevant book by Castellio, De haereticis (1554) was translated by Roland Bainton as Concerning Heretics (1935).

An analysis of Servetian theology in English is to be found in Jerome Friedman, Michael Servetus: A Case Study in Total Heresy (1978). Friedman contributed “Michael Servetus: Unitarian, Antitrinitarian, or Cosmic Dualist?” to the Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1985-86). Also in that issue is “Servetus and the Early Socinians” by Elizabeth F. Hirsch, who also wrote “Michael Servetus and the Neoplatonic Tradition,” in Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance (1980). George Huntston Williams’s The Radical Reformation (1962, revised and expanded, 1992) contributes important perspectives on the place of Servetus amongst other branches of the Radical Reformation. Williams also wrote “Michael Servetus and a theology of nature,” in the Journal of the Liberal Ministry (1964). John Godbey’s “Michael Servetus,” unpublished paper (c. 1987), is a valuable synthesis of current thought about the importance of Servetus in Unitarian theological history. See also Alcalá’s introductions to the Obras Completas. Two bilingual monographs recently published are Ana Gomez Rabal, De Trinitatis Erroribus: A Philological Approach to Michael Servetus (2005) and Jaume de Marcos Andreu, The Influence of Erasmus on Michael Servetus’s Works (2006). Papers delivered at a 450th anniversary conference in Geneva are collected in Clifford M. Reed, ed., A Martyr Soul Remembered (2004). See also Peter Hughes, “Servetus and the Quran,” Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2005) and “The Present State of Servetus Studies: Eighty Years Later,” Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (2010-2011).

Roland H. Bainton’s Hunted Heretic: The Life and Death of Michael Servetus, 1511-1553 (1953) was for a long time the only major modern biography of Servetus in English. A Spanish edition, translated by Angel Alcalá came out in 1973. A new English edition with a new and comprehensive bibliography and updated notes was issued in 2004. It also contains Historia de Morte Serveti (1554), a short account of Servetus’s execution in an English translation by Alexander Gordon. The most recent biography is Marian Hillar, Michael Servetus: Intellectual Giant, Humanist, and Martyr (2002). Hillar also wrote The Case of Michael Servetus (1511-1553): the Turning Point in the Struggle for Freedom of Conscience (1997). On Servetus’s birthdate and the chronology of his youth, see Peter Hughes, “In Search of Servetus’s True Birthdate,” in Sergio Baches Opi and Ana Gómez Rabal, eds., Miguel Servet, Eterna Libertad (2012).

Much of Earl Morse Wilbur’s A History of Unitarianism: Socinianism and its Antecedents (1945)—ten chapters—is given over to the story of Servetus. Wilbur also wrote a short biographical essay introducing The Two Treatises. Charles A. Howe treats Servetus at length in the opening three chapters of For Faith and Freedom (1997). A biographical essay by the celebrated Canadian physician William Osler, “Michael Servetus,” is in the collection, A Way of Life (1951). A recent monograph is Michael Servetus (1989) by A. Gordon Kinder. The quite unreliable Out of the Flames (2002) by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone is more the story of Christianismi Restitutio than of Servetus himself. There is a major modern biography in Spanish, José Barón Fernández, Miguel Servet: su vida y su obra (1970). Wilbur compiled an exhaustive bibliography of works about Servetus in A bibliography of the pioneers of the Socinian-Unitarian movement in modern Christianity, in Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland. (1950).

There are statues of Servetus in rue Mouton Duvernet, Paris, France; Annemasse, Haute Savoie, France; Rue Beausejour, Geneva, Switzerland; Madrid, Spain; Zaragoza, Spain; and Villanueva de Sigena, Spain. Among other memorials are the Servetus window in First Parish Church (Unitarian Universalist) in Brooklyn, New York and the painted medallion of Servetus (staring at another of Calvin) at Brookfield Unitarian Church, Gorton, Manchester, United Kingdom.

Article by Peter Hughes

Posted January 20, 2013

consult the previous version (first posted on August 25, 2000) to compare changes.