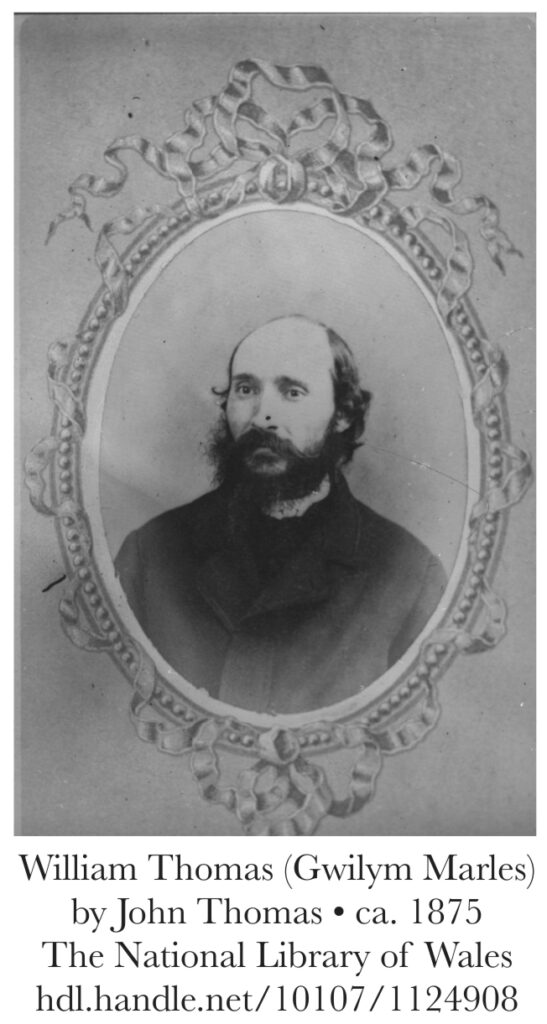

William Thomas (April 7, 1834-December 11, 1879) has been called “the founder of modern Unitarianism in Wales”. He was the minister at the Llwynrhydowen church, which, founded in 1733 as the first Arminian church in Wales, became an anchor of Unitarian religion in a small and isolated region of inland West Wales lying near the River Teifi, which separates Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire. This area, where Welsh Unitarianism flourished, was maliciously dubbed the “Black Spot”. Thomas’s activism on behalf of his congregation culminated in his, and their, being locked out of the church in 1876. He gave a famous address in front of the locked entrance to a crowd of some three thousand. His writing was inspired by personal experience, the principles of Theodore Parker, and the thinking of James Martineau. Besides poems (some used as hymns) and essays, he also published a memoir and a translation of an American novel.

William Thomas (April 7, 1834-December 11, 1879) has been called “the founder of modern Unitarianism in Wales”. He was the minister at the Llwynrhydowen church, which, founded in 1733 as the first Arminian church in Wales, became an anchor of Unitarian religion in a small and isolated region of inland West Wales lying near the River Teifi, which separates Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire. This area, where Welsh Unitarianism flourished, was maliciously dubbed the “Black Spot”. Thomas’s activism on behalf of his congregation culminated in his, and their, being locked out of the church in 1876. He gave a famous address in front of the locked entrance to a crowd of some three thousand. His writing was inspired by personal experience, the principles of Theodore Parker, and the thinking of James Martineau. Besides poems (some used as hymns) and essays, he also published a memoir and a translation of an American novel.

In Wales Thomas is known under the Welsh form of his first name Gwilym and a second name Marles, after a local river. He wrote as Gwilym Marles beginning in the 1840s and under that name has entered modern history books discussing his political leadership as well as histories of Welsh verse, in which he is classified as a nature poet. He signed political and theological writings as “William Thomas”, but his work sometimes appeared anonymously or under other pen names. He was a paternal great-uncle to the poet Dylan Thomas, who was given his middle name Marlais in his honor and whose poetry is indebted to the philosophical tradition that William Thomas embraced.

Thomas was the second of five children born into a farming family living at Glanrhyd-y-gwiail, near Brechfa, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The family had deep roots in the region, a remote area that had produced the first Unitarian minister in Wales, Tomas Glyn Cothi (1764-1833) and that lay at the southern edge of the Unitarian “Black Spot”. Thomas remembered clearly the sermon he heard at the age of 10 or 11 in the Unitarian church at Cwmwrdu, about which he would publish, “Mynwent Cwmwrdu” (“The Cemetery of Cwmwrdu”), one of his best-known poems (1863).

Denominational Sunday schools were at that time the main educational institutions available to the Welsh-speaking majority population, and “The Sunday School” was the topic of Thomas’s first essay, published in a Congregationalist children’s monthly in 1845, when he was eleven years old. At age 12 he was apprenticed to his mother’s brother Seimon Lewis, a cobbler at Nantypoeth, where he lived from 1846 to 1852. He continued to write and publish: a poem appeared in 1848 in Y Diwygiwr (The Reformer), a Congregationalist monthly with radical Nonconformist views, and both poems and essays appear in the Tywysydd Ieuainc (Youth Guide) for 1849. Lewis was a deacon in his Independent (Congregational) church in Gwarnogau. Thomas became a regular member of the Sunday school there, and in January 1850 he conceived the idea of “going down to Melingwm to the school”, which he did, but only for a short time.

Education in Wales was in flux. Responding to unrest in the 1840s, the government, previously uninvolved in education, took new interest in it, but their initiative amplified existing class distinctions. The population of rural Wales was split between, on one hand, the Tory Anglican and anglophone land-owning and gentry classes, and, on the other, the majority of their tenants, small farmers, and laborers, who were Welsh-speaking members of Nonconformist denominations (the “chapels”). Since most members of government school boards were Anglican, many Nonconformists preferred their own schools but were taxed for the public ones. Throughout Britain, Nonconformists were still excluded from Oxford and Cambridge universities, Wales had no universities of its own, and, even if a student acquired a good education, official public life, outside the church, could only be conducted in English. Since the eighteenth century, Nonconformist educational institutions had offered their graduates the possibility of taking leadership roles through the ministry, which thus became one of the few leadership positions open to the Nonconformist Welsh. Because of the financial and demographic constraints of rural Wales, however, Nonconformist schools were often unstable and the level of instruction variable.

Thomas attracted the notice of William Davies (1805-1859), an Independent minister with a school at Ffrwd-y-fâl, an estate near Llansawel. Well educated and liberal in his views, he never suited the several congregations he served over the years, but he was a dedicated and effective teacher. Thomas met Davies on a rainy April night in 1850, when Davies visited Thomas and his family to recruit Thomas for Ffrwd-y-fâl. He was not immediately successful, but a year later Thomas did go there, by then envisioning his future calling as a minister. Toward the end of 1851, when Thomas had been at Ffrwd-y-fâl for about five months, Davies sent him to the Presbyterian-founded institution in Carmarthen, Wales that Davies himself had attended, where he was at that time an external examiner, and where he later taught Hebrew and mathematics.

The institution where Thomas studied from the beginning of 1852 through November 1856 enjoyed an excellent reputation. Started in Carmarthen in the late seventeenth century as the Welsh Academy, it moved to Swansea but in 1794 returned, and continued there until 1963. The school was progressive, tolerant, and scientifically oriented. It began to be referred to as a college in 1828, and when Thomas studied there was run by David Lloyd (1805-1863). A Unitarian minister known among his orthodox enemies as “the Arian of Llwynrhydowen”, Lloyd was conservative, with views old-fashioned in the context of the British Unitarianism of his time, but he succeeded a predecessor said to have systematically denied admission to Unitarian students, even though Unitarianism had been legal in Britain since 1813. Lloyd affiliated the school with the University of London, founded in 1826 as a secular alternative to Oxford and Cambridge and a chartered degree-granting institution. In 1842 the Presbyterian College was granted a royal license to grant certificates for degrees in the University of London, and in 1847 it was re-named the Presbyterian College, Carmarthen.

Thus, when Thomas attended the College, its curriculum and examinations conformed to London requirements. Its students came from a broad swathe of Welsh Protestantism, and the Congregationalists sought places there for their own adherents, among whom was William Thomas. The relationship among the denominations was fluid, in that British Unitarians represented the development of a progressive, rational Christianity favored among the Old Dissenters, notably Welsh Presbyterians, but that also included the Congregationalists, who differed from the Presbyterians more in questions of church governance than in doctrine. All these groups had their own “radical” and “moderate” divisions, all tended to be grouped together because they were excluded by Anglican institutions, and all were clearly distinguished, in Wales, by their rejection of the emotional theology of the newer and ascendant version of Nonconforming Christianity, namely Welsh Calvinist Methodism. Although the College at first limited the number of Congregationalist students, claiming they lowered the educational level, the Congregational churches provided financial support for their co-religionists, and in 1850 all except one of the students were from Congregationalist backgrounds. This was the challenging and modern intellectual environment that Thomas entered in late 1851.

Along with his regular studies, Thomas continued to publish poetry and improved his English by keeping English-language diaries. In 1855 he published his translation of The Sunny Side; or, the Country Minister’s Wife, by American feminist Elizabeth Stuart Phelps in the magazine Seren Gomer (Star of Gomer), as well as a poem in English. That same year Thomas wrote: “To the Trinity Question – must guard myself against Unitarians”, but by mid-summer he had declared himself a sceptic and a Unitarian. In November 1856 he gave his first sermon with the Unitarians at the Parkyvelvet church, which Lloyd had established as a Unitarian chapel, and as the official chapel of the College.

In November 1856 Thomas took up a scholarship from Dr. Williams’s Trust, to study at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, known for its modern and scientific orientation, especially its medical faculty, but also attended by aspiring Nonconformist ministers. His studies focused on his teaching credentials, but, in poor health, he returned to Wales for several months (November 1857 – February 1858), during which he taught the poet Islwyn, and met John Edward Jones, editor of the Unitarian magazine Yr Ymofynydd (The Enquirer), established in 1847 and soon to become the leading Welsh Unitarian periodical. In Thomas’s day it was published monthly and today is the only denominational magazine established before 1850 that continues to appear. In April 1858 Thomas conducted his first services at the Llwynrhydowen and Bwlchyfadfa churches, near Llandysul, Wales. In October, in Swansea, he married Mary Hopkins, returning with her to Glasgow in November. Thomas meanwhile continued writing poetry and published a collection of poems in 1859. The same year he was awarded his B.A. degree, and in April 1860–his M.A.

The Thomases immediately left for Llandysul, where their first daughter was born in September. The couple had three more children, the last born in 1866. Mary Hopkins Thomas died in January 1867, and the couple’s youngest child died only a few months later. William Thomas remarried in January 1869, to Mary Williams, daughter of a law clerk in the Welsh town of Newcastle Emlyn and recently returned from visiting America. James Martineau conducted the ceremony at the Little Portland Street Chapel in London, England. William Thomas and Mary Williams Thomas had seven children together, of whom five survived early childhood.

Llwynrhydowen was, and is, a rural church, the heart of the small Rhydowen (Owen’s Ford) village located on land owned by the local squire. It is famous in Wales for its seminal role in Unitarianism, and because its first minister, Jenkin Jones, was from the family that later, in America, produced the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The connection between Llwynrhydowen and F.L. Wright illustrates the rich connections between Welsh and American Unitarianism. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the connections were nourished by large Welsh emigrations to America, while repression of Unitarianism in Britain, as well as class issues, weakened the ties between the relatively isolated Welsh Unitarians and co-religionists in Engand.

As the settled minister at Llwynrhydowen, Thomas occupied a central position in Welsh Unitarianism, but he also preached at smaller congregations. He was popular with them and successful with the grammar school that he established in Llandysul (1860). In 1862, commemorating the bicentennial of the Great Ejection, he renovated the Llwynrhydowen church and in 1864 started a library there. In the mid-1860’s the school moved into a new, larger building, where the Thomases also lived. It was also used for Sunday evening church services, the last of the three services that Thomas conducted each Sunday. The services in the school building were the beginning of the congregation housed after 1884 at the Capel Y Graig (Chapel of the Rock). Thomas supervised pupils’ work at the school on weekday evenings.

Thomas also wrote prolifically. His best-known prose appeared in Yr Ymofynydd and included his “Cofion a Chyffesiadau”(“Memoirs and Confessions”, 1860-1861) and a long essay “Hanner awr gyda’r Bardd o Bantycelyn” (“Half an hour with the bard of Pantycelyn”, 1863). Thomas’s theological views and their situation in the Welsh Unitarianism of his day is also explicit in his 1863 response to the question presented on the pages of Yr Ymofynydd, “Beth yw Ffydd Gadwedigol” (“What is Redemptive Faith?”). Thomas states that it is not dependent on miracles and is not confined to the New Testament, but rather is differently possible in different historical circumstances; it was the faith of Jesus himself and is accessible to all human beings who have the opportunity to develop their inborn faculties (cyfleusterau). Conservative opponents writing in Yr Ymofynydd (including Thomas’s old headmaster David Lloyd) objected to Thomas’s views and even said they were incomprehensible; since Thomas was to some extent innovating in his use of Welsh religious vocabulary, the incomprehension was probaby unfeigned, but, although he does not mention James Martineau in this context, Thomas would seem to adhere closely to Martineau’s philosophy, expressed in work beginning in the 1840s. Thomas’s propagation of liberal and controversial ideas took its most significant turn in 1864, when he published nine letters under the heading ‘Theodore Parker’. Martineau had responded favorably and at length to Parker’s ideas at an early stage in their development, and a brief excerpt from Parker’s work had appeared in Welsh in Yr Ymofynydd (1863); however, starting from an apt quotation from Martineau and referring to Parker’s death in 1860, and the recent publication of John Weiss’s Life and Correspondence of Theodore Parker, Thomas’s letters survey the whole of Parker’s achievement for new readers and clearly advocate his views and, in particular, Parker’s social engagement on behalf of the oppressed.

When Yr Ymofynnydd suspended publication from 1865 to 1867, Thomas filled in with his own journal, Yr Athro (The Teacher), and he still managed occasionally to write poems. Although his education and the instruction at his school were in English, his mature publications are in Welsh, and his Welsh style has been praised for its purity and adherence to the speech of ordinary people. Thomas’s linguistic choices were entirely natural, but also, in the context of the time, implicitly political. His energetic work in all his varied roles in his community, his theology with its emphasis on individual conscience, and his conversion to Theodore Parker’s social view of religious obligation, entailed a degree of social engagement that led directly to political action.

Thomas’s congregation were mostly tenant farmers. Laws passed in 1866 had expanded suffrage to include tenants, but with no secret ballot. The elections of November 1868 were of near-mythical importance in Welsh history, as tenants cast their first votes against their Tory landlords–who responded with a terrible vengeance. The choice in Thomas’s Carmarthenshire district was between two candidates, Tory and Whig. Thomas actively campaigned for the Whig, E.M. Richards, a Baptist from Swansea whose son was a pupil in Thomas’s school. Richards won, but the tenants known to have voted Whig began to be evicted as “bad farmers” and the evicted families sometimes had nowhere to go except, penniless, into emigration. Others were threatened with eviction unless they removed their children from Thomas’s school and left his church. Thomas continued campaigning, now for the secret ballot.

The political crisis deepened. The secret ballot became law in 1871, but just appearing at the polls remained a public statement. Moreover, Thomas continued his political activity, campaigning during the school board elections of 1871 and the general election of 1874. He also wrote articles describing the plight of tenant farmers. In 1871 he published, anonymously, the history of the Jones family of Ffynnonllewelyn, who tried to emigrate to America but whose children died en route. The parents returned, but soon died themselves. The service for the family, on the eve of their departure for America, had been conducted by Thomas. Thomas had never been physically sturdy, and his life was physically demanding. Now dying of cancer, he complained of exhaustion and needed assistance, but he continued to travel to outlying communities and to conduct his work in Llandysul. Meanwhile, unknown to him, John Davies Lloyd, the owner of the land on which the Llanrhydowen church stood, was planning to force him out.

Until the autumn of 1873, Thomas had been assisted in the evening services at Llandysul by a pastor named Thomas Thomas of Pantydefaid, who then simply ceased to appear. By January 1875 Thomas Thomas was receiving letters from the steward of the estate. The landlord proposed a lifetime lease of the church to Thomas Thomas if he would reserve its use to himself alone, and not permit William Thomas or anyone associated with him to use it. Thomas Thomas acknowledged offering to lease or even buy the church and its cemetery, but he refused to accept the condition to exclude William Thomas. The steward wrote back that the very reason he had made the offer was to force William Thomas and his congregation to leave. No other terms would be acceptable.

In October 1876 William Thomas and his congregation were ordered to cease using the church, and the carpenter Watkyn Davies was ordered to lock the church and cemetery entrance. His protests were vain, but when Thomas arrived in the afternoon on October 29, from his earlier service at Bwlchyfadfa, he found three thousand people standing outside the cemetery. There, at the top of the steps, his back to the cemetery where his first wife and two of his children were buried, Thomas preached his sermon, warning that this persecution was the beginning of a campaign against Nonconformists. He famously declared that the landlord could take the candlesticks, but not the flame: “the flame and the light are God’s, and that will live”. Davies had left a window unlatched for the church Bible and communion set to be brought out for the service, and, that evening, members of the congregation broke in to secure the church records.

The incident brought enormous publicity, nearly all favorable to the congregation, and a successful campaign was launched to build a new chapel. The landowner died leaving his estate to his agent, but his sister successfully contested the will and brought the key to the chapel back from London, to great celebration. Thomas was too ill to attend, or to preach in the new chapel. He died in LLandysul a few weeks later, just 45 years old, and was buried in the new chapel grounds.

His reputation lived on in Wales for several later generations and entered the British Unitarian tradition. The Unitarian minister, journalist, and editor of The Christian Life and Unitarian Herald, D. Delta Evans (1866-1948), was a child in Wales in the 1870s, and in his 1913 autobiographical novel Daniel Evelyn, Heretic he introduces Marles as the person most influential on his eponymous hero’s development. Although the visit Evans describes, from Marles to Evans’s north Wales community, probably never took place, the effect of Marles’s writings, quoted extensively in the novel, was certainly real. By 1937, in contrast, Evans finds it necessary to add a footnote to a mention of Marles in work originally published in 1893, to remind his Welsh readers of who Marles was.

His reputation lived on in Wales for several later generations and entered the British Unitarian tradition. The Unitarian minister, journalist, and editor of The Christian Life and Unitarian Herald, D. Delta Evans (1866-1948), was a child in Wales in the 1870s, and in his 1913 autobiographical novel Daniel Evelyn, Heretic he introduces Marles as the person most influential on his eponymous hero’s development. Although the visit Evans describes, from Marles to Evans’s north Wales community, probably never took place, the effect of Marles’s writings, quoted extensively in the novel, was certainly real. By 1937, in contrast, Evans finds it necessary to add a footnote to a mention of Marles in work originally published in 1893, to remind his Welsh readers of who Marles was.

Partly because of circumstances surrounding Thomas’s health, Thomas’s large family had been forced to separate, and several of the children were placed outside the home. On his death, Thomas’s widow was left to arrange the fates of eight children, three under the age of six. In response, the church raised a fund to support the family, and, although not all the children’s later lives seem to be documented, the later life of the family largely continues in the path William Thomas had established.

His widow, who died June 12, 1903, ran a school in Carmarthen and later in Aberystwyth, Wales that prepared girls for higher education. On her death, Mrs. Mary Marles-Thomas was praised as an educator and for her role in public life. She was president of the Carmarthen Women’s Liberal Association, testified at hearings of a Land Commission in Carmarthen, and was an effective public speaker on issues of political and social concern. She was an educational reformer who believed both in making childhood happy (a relatively new idea in her day) and in educating women. At least the three youngest of Thomas’s daughters (Mary Emerson, Lisa, and Muriel) graduated from college. The daughters who are known to have married did so in Unitarian chapels. In 1891 Annie Janet married a Unitarian minister, S.H. Street, in the Park-y-velvet chapel in Carmarthen; she died in 1954 at the age of 89. In 1898 Mr. Street assisted at the marriages of two of his sisters-in-law. In August, Muriel married Adam Sedgwick Barnard at the Platt Chapel in Manchester, in a ceremony conducted by Mr. Street assisting his father the Rev. J.C. Street, and, in September, in Llwynrhydowen, Lisa married S.P. James, a specialist in tropical diseases who served the Indian Medical Service and wrote several books in his specialty. Mary Emerson did not marry but continued her mother’s work at their school; after her death in 1934 she was warmly memorialized for her success in promoting her girls’ health and happiness, as well as providing them with an enlightened education. The two sons who are known to have survived to adulthood both died relatively young; Theodore Parker Marles Thomas, the elder of the two, died December 3, 1904 in Hong Kong, aboard the ship where he was the surgeon. The youngest child, Lewis Williams Thomas, was killed in military action while serving as chief officer on a merchant ship on April 29, 1917. Muriel Barnard died in 1943. During the interwar years, S.P. James was in charge of the Malaria Commission and the Epidemic Commission of the League of Nations. He died in 1946.

The old chapel at Llwynrhydowen—now a museum—still houses the church library established in 1864, including books collected by William Thomas. Of special interest is an early Welsh commentary on the Bible, a work apparently unknown to the public until 1897. A small collection of William Thomas’s poems and essays, in Welsh, are in Gwilym Marles, Ab Owen, n.d., Llanuwchllyn, Gwynedd, Wales (1905). Welsh readers can consult the detailed biography of Thomas, illustrated with copies of important documents, by Nansi Martin, Gwilym Marles, Gomer Press in Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales (1979). A good thumbnail sketch of Thomas, based on archival sources, is David Jacob Davies, “Thomas , William (Gwilym Marles; 1834-1879)” in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography (DWB).

For more on the relationship between William Thomas’s Unitarianism and the poetry of his great-nephew Dylan Thomas, see M. Wynn Thomas “‘Marlais’: Dylan Thomas and the ‘Tin Bethels'” In the shadow of the pulpit: Literature and Nonconformist Wales (2010). For more on his extended family see David N. Thomas, ed. Dylan Remembered. Vol. 1, Seren Books, Bridgend, Wales (2003). A Comprehensive and systematic overview of Welsh Unitarianism and Religious Nonconformity, including a useful map of the Unitarian “Black Spot,” is found in D. Elwyn Davies, “They Thought for Themselves:” in A brief look at the history of Unitarianism in Wales and the tradition of Liberal Religion (1982). Also useful for context is David Russell Barnes, People of Seion: Patterns of Nonconformity in Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire in the century preceding the Religious Census of 1851, Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales (1995). William Thomas and Unitarianism in Wales are covered in Earl Morse Wilbur, A History of Unitarianism: In Transylvania, England and America: Volume II (1952).

Welsh readers can consult the well-researched and systematic study by the Llwynrhydowen minister Aubrey J. Martin, Hanes Llwynrhydowen (A History of Llwynrhydowen) Gomer Press, Llandysul, Wales (1977). It includes a catalog for the Llwynrhydowen Chapel library and a list of ministers. A good presentation of Welsh Unitarianism in historical context with special chapters on Arminianism and Arianism in Wales, and a chapter on Theodore Parker, James Martineau, and Gwilym Marles is found in T. Oswald Williams, Undodiaeth a rhyddid meddwl (Unitarianism and Freedom of Thought), (1962). More on Thomas and his father can be found in W. J. Davies, Hanes Plwyf Llandyssul (History of Llandysul Parish), Gomer Press, Llandysul, Wales (1992 facsimile reprint of 1896 first edition).

An unequaled Internet resource—with architectural descriptions, virtual tours of Welsh religious buildings, and histories of the denominations that worshiped or worship in them—has been compiled by the Welsh Religious Buildings Trust (Addoldai Cymru) as The Story of Nonconformity in Wales. It can be accessed at < welshchapels.org >. Other useful Internet resources are the Dictionary of Welsh Biography (DWB); Welsh Newspapers Online at < newspapers.library.wales >; Denominational Magazines in the On-line Collections of the National Library of Wales at < llgc.org.uk >; and Dissenting Academies Online—an Internet database developed by the Queen Mary Research Centre for Religion and Literature in English—available at < qmulreligionandliterature.co.uk >. Information on Unitarians in Wales can also be found on the Bilingual British Unitarian Website at < ukunitarians.org.uk >. Unitarian Obituaries, a project of Harris Manchester College can be consulted at < unitarianobituaries.org.uk >.

Article by Emily Klenin

Posted September 25, 2016