Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817-May 6, 1862) was a person of many talents and interests: surveyor, pencil-maker, naturalist, lecturer, schoolteacher, poet, anti-slavery activist, and spiritual seeker, to name but a few. He is best known as a member of the Transcendentalist circle of writers and religious radicals, and author of numerous books and essays, especially Walden and “Resistance to Civil Government,” better known as “Civil Disobedience.”

Born in Concord, Massachusetts, his parents named him David Henry Thoreau. Except for a brief period in his early childhood, he lived in Concord all his life, “the most estimable place in all the world.” His father, John, was a shopkeeper who, later on, turned to the manufacture of pencils. His mother, Cynthia, was active in charitable causes and a founder of the Concord Women’s Anti-Slavery Society. His siblings included a brother, John, and two sisters, Helen and Sophia. Concord, a rural farm town about 20 miles northwest of Boston, would later become home to several of the most prominent members of the Transcendentalist group, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Bronson Alcott. Thoreau was the only Concord native in the group.

Thoreau’s parents were members of First Parish Church for many years under the ministry of Ezra Ripley. Ripley baptized David as an infant and catechized him as a child. When he was ten years old, the parish was split with the founding of the Trinitarian church in Concord. His mother’s sisters went over to the rival congregation and implored Cynthia to join them. She quit First Parish, but found that her free-thinking religious views were not welcome among the Trinitarians. She returned to the family pew at the Unitarian church, much to the relief of Rev. Ripley, and along with her husband remained a member there for the rest of her life.

The family was far from well-to-do and determined that they could only afford to send one of their two sons to college. They chose David, the more studious of the two, over his older brother. He entered Harvard at the then not unusually early age of sixteen. He seems to have passed unnoticed by most of his fellow classmates. In need of income to complete his studies, he dropped out for several months during his junior year to teach, living with Orestes Brownson then a Unitarian minister in Canton, Massachusetts. In a commencement essay, he announced the order in which he resolved to live his life:

The order of things should be somewhat reversed,—the seventh should be man’s day of toil, wherein to earn his living by the sweat of his brow; and the other six his Sabbath of the affections and the soul, in which to range this widespread garden, and drink in the soft influences and sublime revelations of Nature.

In search of a vocation, Thoreau found a teaching position with the town school but resigned when instructed by a member of the school committee to flog his students. After a futile search for teaching positions elsewhere he and his brother took over the Concord Academy, introducing numerous reforms in curriculum and teaching methods. Three years later John’s health gave out, forcing the closure of the school. Shortly thereafter, in 1841, Henry David moved into the Emerson household as handyman and gardener remaining for a period of two years. A proposal of marriage to Ellen Sewell, daughter of a Unitarian minister, came to naught and he remained a bachelor the rest of his life.

By this time he had come under the influence of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who mentored him in his fledgling career as a writer. Emerson had written a letter recommending financial assistance for Thoreau while he was a student at Harvard. He encouraged him to keep a journal, welcomed him into the Transcendental Club which met from time to time at the Emerson home, and sought to place his poems, essays and extracts from “Ethnical Scriptures” in the Dial magazine, a Transcendentalist periodical. In developing his identity as a writer, Thoreau decided to change his name from David Henry to Henry David.

His first major publication, in the Dial for July of 1842, was an essay on “The Natural History of Massachusetts,” foreshadowing his reputation as an ecologist and environmental writer. This was followed by “A Walk to Wachusett” and “A Winter Walk,” both published in 1843. In hopes of furthering Thoreau’s career as a writer, Emerson secured a position for him as a tutor for his brother’s children on Staten Island where Thoreau might also meet with New York publishers. Frustrated and homesick, he stayed for barely six months, though he did manage in that time to find an influential benefactor and literary agent in Horace Greeley, publisher of the New York Tribune.

On his return to Concord, Thoreau rejoined his father in the family pencil business. His improvements to their product made it the best on the market at the time. His relationships with Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Ellery Channing (nephew of William Ellery Channing) deepened in this period and strengthened his resolve to become a successful author. The tragic death of his brother from lockjaw in January 1842 was devastating and prompted him to write, as a memorial, an account of a trip they had taken together by boat up the Concord and Merrimack rivers in 1839.

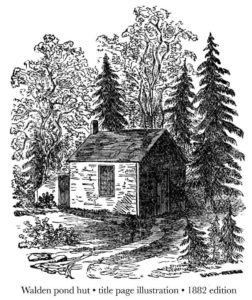

From his college days, Thoreau had toyed with the idea of building a cabin in the woods where he might seek solitude and commune more closely with nature. By this time, he had made it a habit to spend a good portion of each day year-round sauntering, as he called it, in the woods and fields in the vicinity of Concord. In the spring of 1845 he commenced building his cabin near the shore of Walden Pond on property owned by Emerson. There, in his “inkstand in the woods,” he found the quietude and inspiration he needed to complete his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. He also began to compose Walden, an account of his twenty-six month stay at the pond in the form of a manual on self-culture and simple living.

Contrary to some impressions of him, Thoreau was not reclusive, even during this time. As much as he enjoyed solitude and nature, he took pleasure in socializing with friends and neighbors and keeping up with the local gossip. He frequently walked to town on errands and to dine with his family or the Emersons. It was on one of these visits, in July of 1846, that he was approached by the town jailer and tax-collector who informed him that he had not paid his poll tax for the past several years. He refused to pay the tax as a silent protest against slavery and, most recently, the U.S. invasion of Mexico. When he told the tax-collector that he had no intention of paying, he was taken to the Concord jail where he was released the next day after someone, perhaps one of his aunts, paid his tax.

He recounted his famous night in jail in a lecture given at the Concord Lyceum in January 1848. It was subsequently published as “Resistance to Civil Government“ in Elizabeth Peabody’s Aesthetic Papers. After his death the essay was retitled “Civil Disobedience,” and in time exerted a major influence on non-violent protest movements in South Africa, India, and the U.S. While Thoreau does not advocate violence in this essay, it is not clear that he is a pacifist. He adheres to the fundamental Transcendentalist principle that there is a higher law than the civil law and that when there is a conflict between the two, it is the citizen’s duty to heed the voice of conscience rather than collude in oppression. “Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?” He left no doubt as to his own choice, asserting, “If it is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law.”

He left his cabin at the pond in 1847 when Emerson asked him to move back into the Emerson home to look after his family while he went to England on a lecture tour. Emerson was gone for a period of ten months. Though he became close to Emerson’s wife and children during this time, his relationship with Emerson himself had become strained. As he matured as a writer, he sought to break free of Emerson’s tutelage. Moreover, he bristled at Emerson’s disapproval of his decision to go to jail rather than pay his tax. Emerson’s illness a few years later seems to have eased the tension in their relationship. “We must accept or refuse one another as we are,” he wrote.

Thoreau’s book, A Week was published, at his own expense in 1849. To his dismay, it was not well received and many copies went unsold. Of particular note to those interested in his religious views are the “Sunday” and “Monday” chapters. He rejects organized religion characterized by creedal formulations, chauvinist sectarianism, and moral hypocrisy, in favor of a religious perennialism and, in Alan Hodder’s words, “a theology of ecstatic experience.” He favorably compares the Greek god Pan with Jehovah, the Buddha with Jesus and the Bhagavad Gita with the Christian Bible, much to the annoyance of his critics.

As demonstrated in A Week, Thoreau was a serious student of Eastern religion and philosophy. He was especially drawn to the Vedanta teachings of the Bhagavad Gita and to some extent modeled his life at Walden Pond on the instructions given to adepts of yoga in this text. He had taken Emerson’s copy of the book with him to the pond and once declared in a letter to a friend, “Depend upon it that rude and careless as I am, I would fain practise the yoga faithfully…. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogin.”

His signature achievement as a writer is Walden, which finally appeared in 1854 after numerous revisions. The book is structured in such a way as to condense his two-year stay at the pond into one cycle of the seasons, from summer to the following spring. The symbolism of the seasons is meant to suggest a process of spiritual awakening and rebirth in keeping with what he and the Transcendentalists termed self-culture or the cultivation of the soul. In the course of the book, he outlines a spiritual practice consisting of reading, leisure, solitude, vegetarianism, journal writing, simple living, communion with nature and action from principle, all geared toward increased awareness and self-reliance: “I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but such is the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can never make to dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.”

With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1851, Thoreau became increasingly strident in his attacks on the government. He delivered an incendiary speech, “Slavery in Massachusetts,” in Framingham on July 4, 1854. “I walk toward one of our ponds, but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base?” he asked. “Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.”

His most controversial and consequential anti-slavery addresses were those in defense of John Brown. “I am here to plead his cause with you. I plead not for his life, but for his character,” he stated in his impassioned “Plea for Captain John Brown” following Brown’s capture and trial in 1859. “Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified; this morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain which is not without its links. He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an Angel of Light.” Along with Emerson’s defense of Brown, Thoreau’s plea was widely reported in the press, causing a rift between the Northern and Southern wings of the Democratic Party. As a result, the party fielded two slates of candidates, allowing Lincoln to win the election of 1860 which, in the view of many historians, would not have happened otherwise.

During the last ten years of Thoreau’s life his voluminous journals were increasingly devoted to cataloging observations of flora and fauna on his daily walks. These provided the substance of two major books published long after his death, Faith in a Seed and Wild Fruits. So detailed were these observations that they have contributed to the study of climate change from his time to the present. His celebration of the natural world is best expressed in a late essay, “Walking,” in which he remarks, “I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil,—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.” Many, including Lawrence Buell, have credited him with introducing a “green,” or ecocentric perspective in environmental writing.

Following one of his walks in December 1860, he came down with a severe cold which developed into bronchitis and eventually into acute tuberculosis. The following year he traveled to Minnesota in hopes of recovery, but to no avail. Realizing that his time was limited he began to prepare a number of his lectures for publication. “Walking,” “Wild Apples,” “Autumnal Tints” and “Life Without Principle” were published posthumously. The Maine Woods and Cape Cod, both of which were based on trips he had taken to these areas, appeared within two years of his death. In his final months, as he lay on this deathbed in the living room of the family home, friends and neighbors came to call. A few days before his death a friend leaned towards him and said, “You seem so near the brink of the dark river that I almost wonder how the opposite shore may appear to you.” “One world at a time,” was Henry’s reply.

At Emerson’s insistence, Thoreau was buried out of First Parish Church. Grindall Reynolds, then minister of the church, read selections from the Bible and offered a prayer. Emerson gave the eulogy, lamenting his friend’s untimely death: “The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost. It seems an injury that he should leave in the midst of his broken task, which none else can finish,—a kind of indignity to so noble a soul, that it should depart out of Nature before yet he has been really shown to his peer for what he is.” Over three hundred children, released from school by Bronson Alcott, walked in procession as his coffin was carried from the church to the burying ground.

Thoreau was not a Unitarian in any formal sense of the term. Though he was raised in the Unitarian church and his family remained members of First Parish, he made a point of signing off from the rolls there when, as an adult, he was presented with a tax bill for the support of a minister he did not like. This was Barzillai Frost, the same minister mentioned, also unfavorably, in Emerson’s “Divinity School Address.” Hoping to avoid a rift in the congregation over the issue of abolition, Frost opposed mention of the issue in the church. Thoreau did, however, from time to time attend services of ministers he approved of, including Unitarians Henry Ware, Jr. and Daniel Foster.

The Transcendentalists with whom he associated were almost all Unitarians, and most of them were ministers or former ministers. Despite his Unitarian upbringing, associations, and occasional church attendance, he readily confessed that “What in other men is religion is in me love of nature.” A friend, newly arrived in Concord, had been informed that there were three religious societies in the town: the Unitarian, the Orthodox, and the Walden Pond Society. Without question, he was most faithfully a member of the third. Ironically perhaps, his religious non-conformity, love of nature and action from principle have drawn many like-minded spiritual seekers to Unitarian Universalist congregations.

Thoreau’s reputation as a writer and thinker developed slowly. Though his books remained in print he was viewed primarily as a nature writer with a limited audience. The publication of his journals in 1906 presented a view of his inner life and thoughts, containing “all his joy, his ecstasy.” His social and philosophical issues were not initially popular in this country although they exerted an influence on Tolstoy, Gandhi, and the founders of the British Labour Party. The tide of opinion turned during the depression years as people such as Helen and Scott Nearing sought to practice the art of simple living. The civil rights era and the Vietnam War brought Thoreau’s more radical political thoughts to the fore. Concern for the environment and wilderness preservation have made Thoreau’s ideas on these matters increasingly relevant. Recent scholarship by Unitarian Universalist scholars such as David Robinson and Robert Richardson, Jr. have focused on his religious and spiritual message which has long attracted the interest of religious liberals and seekers on the spiritual left.

Sources

Major collections of Thoreau’s manuscripts are held at the Huntington Library, the Morgan Library and in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. His works have been widely published and often anthologized. The most scholarly edition, including his books, journals and letters, is The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau (1971-) currently in 17 volumes published by Princeton University Press. A previous edition of his works, in 20 volumes, was issued in 1906. Not included in these multi-volume editions are Faith in a Seed, ed. Bradley P. Dean (1993) and Wild Fruits, ed. Bradley P. Dean (2000). His letters are available in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, ed. Walter Harding and Carl Bode (1958). A briefer selection, Letters to a Spiritual Seeker, ed. Bradley P. Dean, was published in 2004. The best single volume edition of his major works is The Library of America’s, Thoreau: A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, Walden, The Maine Woods and Cape Cod (1985), selected by Robert F. Sayre. For his poems and essays see the Library of America volume, Thoreau: Collected Essays and Poems (2001), selected by Elizabeth Hall Witherell. Annotated editions of Walden (2004), I to Myself, selections from Thoreau’s Journal (2007), and selected Essays (2013), ed. Jeffrey S. Cramer, have been published by the Yale University Press.

Digital resources are also extensive. These include:

- The Thoreau Society at thoreausociety.org

- The Thoreau Institute at walden.org

- The Thoreau Reader at thoreau.eserver.org

- The Thoreau Society Collections at archive.org/details/thoreausociety

- The American Transcendentalism Web at transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu/

Two major biographies of Thoreau are The Days of Henry Thoreau by Walter Harding (1965) and Henry David Thoreau: A Life of the Mind by Robert D. Richardson, Jr. (1986). A valuable reference for the details of Thoreau’s life is The Thoreau Log: A Documentary Life of Henry David Thoreau 1817-1862 by Raymond R. Borst (1992). His relationship with Emerson is the subject of My Friend, My Friend: The Story of Thoreau’s Relationship with Emerson by Harmon Smith (1999). Also of interest is Walden Pond: A History by W. Barksdale Maynard. A still useful though somewhat dated bibliographical reference is The Transcendentalists: A Review of Research and Criticism, ed. Joel Myerson (1984).

The critical literature on Thoreau is quite extensive. Important studies include The Shores of America: Thoreau’s Inward Exploration by Sherman Paul (1958), The Magic Circle of Walden by Charles R. Anderson (1968), The Senses of Walden: An Expanded Edition by Stanley Cavell (1981), Seeing New Worlds: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science by Laura Dassow Walls (1995), Reimagining Thoreau by Robert Milder (1995), The Transcendental Saunterer: Thoreau and the Search for Self by David C. Smith (1997), Thoreau’s Living Ethics: Walden and the Pursuit of Virtue by Philip Cafaro (2004), and Natural Life: Thoreau’s Worldly Transcendentalism by David M. Robinson (2004). Valuable collections of critical essays include Critical Essays on Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, ed. Joel Myerson (1988), The Cambridge Companion to Henry David Thoreau, ed. Joel Myerson (1995), A Historical Guide to Henry David Thoreau, ed. William E. Cain (2000) and More Day to Dawn: Thoreau’s Walden for the Twenty-first Century, ed. Sandra Harbert Petrulionis and Laura Dassow Walls (2007).

General works on Transcendentalism include American Transcendentalism, 1830-1860: An Intellectual Inquiry by Paul F. Boller, Jr. (1974), Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830-1850 by Anne C. Rose (1981), “Roots of Unitarian Universalist Spirituality in New England Transcendentalism” by Barry M. Andrews (1992 UUMA Selected Essays), Restless Souls: The Making of American Spirituality by Leigh Eric Schmidt (2005), The Transcendentalists by Barbara L. Packer (2007) and American Transcendentalism: A History by Philip F. Gura (2007).

Thoreau’s religious views are the subject of Thoreau: Mystic, Prophet, Ecologist by William J. Wolf, Thoreau as Spiritual Guide by Barry M. Andrews (2000), Thoreau’s Ecstatic Witness by Alan D. Hodder (2001) and The Spiritual Journal of Henry David Thoreau by Malcolm Clemens Young (2009). His assimilation of Eastern religion and philosophy is explored in The Orient in American Transcendentalism by Arthur Christy (1932), Oriental Religions and American Thought: Nineteenth Century Explorations by Carl T. Jackson (1981), American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions by Arthur Versluis (1993) and The Gita within Walden by Paul Friedrich (2008). Records of the Thoreau family religion and First Parish Church are found in Meeting House on the Green: A History of First Parish in Concord and its Church, ed. John Whittemore Teele (1985) and “Faith in the Boardinghouse: New Views of Thoreau Family Religion” by Robert A. Gross (Thoreau Society Bulletin, Winter 2005).

Thoreau’s social and political views are described in After Walden: Thoreau’s Changing Views on Economic Man by Leo Stoller (1957), The Economist: Henry Thoreau and Enterprise by Leonard N.Neufeldt (1969), Several More Lives to Live: Thoreau’s Political Reputation in America by Michael Meyer (1977), America’s Bachelor Uncle: Thoreau and the American Polity by Bob Pepperman Taylor (1996) and A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau, ed. Jack Taylor (2009). His antislavery activities and support of John Brown are examined in John Brown, Abolitionist by David S. Reynolds (2005) and To Set This World Right: The Antislavery Movement in Thoreau’s Concord by Sandra Harbert Petrulionis (2006). His contributions to environmentalism and nature writing are the subject of The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of the American Canon by Lawrence Buell (1995), A Wider View of the Universe: Henry Thoreau’s Study of Nature by Robert Kuhn McGregor (1997) and Dark Green Religion: Nature, Spirituality and the Planetary Future by Bron Taylor (2010).

Article by Barry Andrews

Posted March 30, 2014