Hendrik Willem van Loon (January 14, 1882-March 11, 1944), a Dutch-American author and illustrator, was the first winner of the Newbery Medal for The Story of Mankind. He was beloved by the public during his lifetime as an engaging, energetic interpreter of the arts and humanities. Now that lively, well-illustrated non-fiction books for all ages are widely available, his reputation has faded.

Born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, the son of Elisabeth Johanna Hanken and Hendrik Willem van Loon, Hendrik Willem was baptized a Lutheran. He claimed to have been raised in a “strict form of Calvinism,” and was nevertheless “completely indifferent to the claims of any church.” He attended schools in Gouda and Voorschoten, including the prestigious Noorthey Institute. In 1902 he emigrated to the United States to study at Cornell University. He transferred to Harvard in 1903 but returned to Cornell the following year, receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1905. After graduation, he found work as a journalist, filing reports for the Associated Press from Russia and elsewhere.

In 1906, van Loon married Eliza Ingersoll Bowditch, daughter of a prominent Harvard physiology professor and great-granddaughter of Unitarian Nathaniel Bowditch, the New England scientist and mathematician. They had two sons, Henry Bowditch and Gerard Willem. When the newlyweds moved to Munich, they attended the American (Episcopal) Church of the Ascension for social and intellectual reasons. Although van Loon served briefly on the vestry, he regarded the worship services as dispensable “hors d’oeuvres.” He later claimed that he had “never associated . . . with a definitely organized religious group” until he joined New York City’s All Souls (Unitarian) Church at the age of sixty.

Van Loon earned his Ph.D. from the University of Munich in 1911. His thesis became his first book, The Fall of the Dutch Republic, 1913, and was followed by The Rise of the Dutch Kingdom, 1915. Although few copies of either book were sold, van Loon was praised by at least one reviewer for daring to “write history as if he enjoyed it.” His Cornell professor, George Lincoln Burr, however, deplored his occasional careless lapses in historical accuracy, as did Dutch reviewers. Having returned to the United States after receiving his doctorate, van Loon resumed work in Europe for the Associated Press during the First World War. He became an American citizen in 1919.

He returned to Cornell as a lecturer in history, 1915-17. His flamboyant presentations were popular with students but failed to prepare them to pass departmental exams. Accordingly, his peers judged him an inept instructor and ill-suited to a scholarly career. Although he later served as head of the Department of Social Sciences at Antioch College, Ohio, 1921-22, he henceforth regarded his academic colleagues as petty adversaries determined to persecute him for his popularity.

After van Loon’s unfaithfulness ended his marriage to Eliza Bowditch, he wed Eliza Helen “Jimmie” Criswell in 1920 and then playwright Frances Goodrich Ames in 1927. After his divorce from Ames he returned to Criswell, albeit pursuing other women from time to time. There are conflicting accounts on whether they remarried. When he died, obituaries listed Criswell as his widow and she inherited his estate.

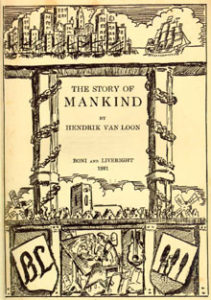

As he labored over The Short History of Discovery, 1917, Ancient Man, 1920, and The Story of Mankind, 1921, van Loon became acquainted with Leonore St. John Power, a children’s librarian at the New York Public Library. She encouraged his efforts to render history in a style accessible and entertaining to all ages. The first edition of The Story of Mankind included a reading list she had compiled at his request. The head of Power’s department, Anne Carroll Moore, came to share her admiration of van Loon. An influential critic of juvenile literature, Moore hailed The Story of Mankind as “the most invigorating and, I venture to predict, the most influential children’s book for many years to come.”

Lavishly praised in the press as a future classic, The Story of Mankind was selected as the first book to receive the annual Newbery Medal, which had been created by Unitarian bookseller and editor Frederic Melcher to honor outstanding American children’s books. The award, bestowed in 1922, cemented The Story of Mankind‘s status as a landmark in the field.

Van Loon did not shy away from controversial statements. In The Story of Mankind he began with an extended treatment of evolution. He chose not to mention the biblical account of creation. The activities of “Joshua of Nazareth,” told using the device of an exchange of letters between a Roman physician and his nephew, are depicted as a political rather than a spiritual matter, with no mention of miraculous works. Such heresies reportedly deterred a number of libraries from acquiring the book.

An avowed skeptic, van Loon left the Immaculate Conception and the Resurrection out of his subsequent The Story of the Bible, 1923. Reviews were mixed. Gerard van Loon thought that his father, had done “his best with material that basically bored him.” The book consequently lacked the panache that had propelled its predecessor to the bestseller lists.

Van Loon’s tendency to insert himself into his narratives was a source of entertainment to some readers and of vexation to others. In The New York Times, John Chamberlain noted “When Hendrik Willem van Loon writes history, you can be certain of getting both plenty of history and plenty of van Loon.” One of his quirkiest efforts, Van Loon’s Lives, 1942, was devoted to imaginary dinner parties, featuring guests ranging from Plato and Confucius to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson, and containing digressions on such topics as the author’s aversion to lamb.

A more serious charge against van Loon was the sloppiness of his scholarship. He manufactured details to aid his narrative, perpetrated anachronisms, and committed other mistakes. Insisting that his own belief in his text was sufficient, he regarded editors and proofreaders as interfering nuisances. His partisans argued that, as he made history come to life, his factual errors were inconsequential.

Because of the success of his early books, van Loon was able to devote the second half of his life to writing. He illustrated most of his own books and occasionally those of others—for example, Stephen H. Fritchman’s Men of Liberty: Ten Unitarian Pioneers, 1944. In addition to contributing columns and cartoons to The Nation, The Rotarian, Forum and other magazines, he served as an associate editor of The Baltimore Sun, 1923-24.

Van Loon had joined the Unitarian Laymen’s League in 1924. He was listed on their rosters until 1933. The League raised money for the American Unitarian Association (AUA), financed mission projects, coordinated special events, and recruited potential ministers. He presented a lecture on “Tolerance” at All Souls Unitarian Church, New York in 1925.

In his book, Tolerance, 1925, van Loon asserted, “The human race is possessed of almost incredible vitality. It has survived theology. In due time it will survive industrialism.” Although he admitted to an occasional chat with God, whom he pictured as “a sort of beneficent grandfather,” van Loon generally had little patience for myths. “There is no Providence. There is no Guidance. No Divine Purpose,” he wrote a friend. He insisted, rather, that “we ourselves are responsible for everything we do—no stars, no spooks, no psychic phenomena.” This belief fueled his determination to publicize and celebrate the inventions and accomplishments of human beings with evangelical zeal.

In addition to many public lectures, beginning in 1935 van Loon delivered talks on radio—notably for NBC—and appeared on Information Please and other celebrity quiz shows. As “Oom Henk” (“Uncle Hank”) he broadcast anti-Nazi speeches to Holland during the Second World War. He also assisted European refugees. In 1942 he was knighted by Queen Wilhelmina for his contribution to the Dutch resistance.

Van Loon participated in Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1940 presidential campaign. Roosevelt considered him “a true and trusted friend,” and admired van Loon’s Our Battle—Being One Man’s Answer to “My Battle” by Adolf Hitler, 1938, in which he exhorted Americans to fight totalitarianism. Van Loon defied his doctor’s caution against overwork in order to chair a division of the National War Fund.

Wishing to connect with potential allies in his battle against wishful thinking, in 1942 van Loon signed the membership book at All Souls. The minister, Lawrence I. Neale, had been a classmate at Harvard and an usher at his first wedding. In his pamphlet for the AUA, This I Believe!, van Loon quipped that the Unitarian Church appealed to him “because the only time the name Jesus Christ is uttered is when the janitor falls downstairs.” He envisioned young Unitarians populating intellectual “shock troops” to combat fantasies of an instant postwar utopia.

In failing health, van Loon did not attend All Souls after he appeared in the pulpit the Sunday he joined. Neale presided at the funeral. The well-attended service featured readings of twelve “prophetic voices,” ranging from the early apostles to Thomas Jefferson and William Ellery Channing.

To van Loon, human achievement mattered above all things. “I have tried to show that Man is the center of the universe.” Seldom modest, he regarded himself as too progressive for his era. His books have not aged well; almost all of them are now out of print. His style, once praised as daring and innovative, now seems quaint and mannered. Because of his racial and social bias and his disdain for historical precision, his books can no longer be used as classroom or reference texts. He nevertheless brought to light a previously unaddressed demand for well-narrated popular histories. His own work has since been eclipsed by the expectations he himself helped raise.

Sources

The Hendrik Willem van Loon Papers are kept in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York. The letters of Eliza Bowditch van Loon are at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Their son Gerard van Loon published some of these as Letters from a Boston Bride. Information on van Loon’s participation and membership at All Souls Church, New York City is in their archives. Among van Loon’s works not mentioned above are The Golden Book of the Dutch Navigators (1917); The Story of America (1927); The Life and Times of Pieter Stuyvesant (1928); Man the Miracle Maker (1928); R. v. R.: The life and Times of Rembrandt van Rijn (1930); “If the Dutch Had Kept Nieuw Amsterdam,” in If, Or History Rewritten, edited by Philip Guedala (1931); Van Loon’s Geography (1932); “Hints for Reformers,” Atlantic (December 1934); An Elephant Up a Tree (1933); Ships and How They Sailed the Seven Seas (1935); his radio talks, Air Storming (1935); The Arts (1937); How to Look at Pictures (1938); The Story of the Pacific (1940); The Life and Times of Johann Sebastian Bach (1940); Thomas Jefferson (1943); the Life and Times of Simon Bolivar (1943); and “Every Man a Historian,” Rotarian (May 1944). With Grace Castagnetta he compiled several songbooks, including The Songs We Sing (1936), Christmas Carols (1937), Folk Songs of Many Lands (1938), and The Songs America Sings (1939). Van Loon also wrote an unfinished, posthumously published autobiography, Report to St. Peter (1947).

The biographies of van Loon are Cornelis A. van Minnen, Van Loon: Popular Historian, Jounalist, and FDR Confidant (2005) and Gerard Willem van Loon, The Story of Hendrik Willem van Loon (1972). Richard O. Boyer wrote a three-part profile of van Loon, “The Story of Everything,” in The New Yorker (March-April, 1943). There are obituaries in the New York Times (March 12, 13, and 15, 1944) and other major periodicals. Frederic Melcher paid tribute to him in “Three Good Men,” Publisher’s Weekly (March 18, 1944). There is an entry by Stephen Anderson Mihm in American National Biography (1999). Profiles of van Loon as a writer and his place in literature include David Karsner, “Hendrik Willem van Loon,” in Sixteen Authors to One: Intimate Sketches of Leading American Storytellers (1928, republished 1968); Anne Carroll Moore, “Hendrik Willem van Loon and ‘The Story of Mankind,'” in Bertha Mahony Miller and Elinor Whitney Field, eds., Newbery Medal Books, 1922-1955 (1955); Joan Shelley Rubin, The Making of Middlebrow Culture (1992); and Bette J. Pettola, “Hendrik Willem van Loon,” in Anita Silvey, ed., Children’s Books and Their Creators (1995).

Thanks to Amy Strano and Lorraine Allen at All Souls Church, New York City for their assistance.

Article by Peg Duthie

Posted January 27,2005