Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (November 11, 1922-April 11, 2007) was an American novelist also known for short stories, essays, and plays. His writing often displays a darkly comic and satirical style revealing serious moral commentary, sometimes through the medium of science fiction. Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, he came from a line of cultured German immigrant skeptics, including a great grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut, a freethinker who wrote a book called Instruction in Morals and translated Robert G. Ingersoll’s essay on Thomas Paine into German. Another ancestor arrived in America with six hundred books.

Vonnegut’s father, Kurt Vonnegut Sr., like his father before him, was a prominent Indianapolis architect; his mother, Edith (born Lieber), came from a family of wealthy brewers. The Vonneguts were members of All Souls Unitarian in Indianapolis, and Kurt Sr. had designed the congregation’s first building. Unitarian minister Francis Scott Corey Wicks married them, and the family attended church twice a year and prayed at meals. Vonnegut Jr. wrote later that he “had learned from them that …racial prejudices are stupid and cruel.”

Vonnegut had an older brother and sister. Bernard became a scientist at General Electric; and Alice, a sculptor. As an artist, she was an inspiration to Kurt. His parents had been disoriented by the anti-German sentiment that surrounded World War I and consequently had passed little of the family tradition to him. He claimed that the black family cook, Ida Young, gave him his moral education and that “the compassionate, forgiving aspects of his beliefs” came from her.

Vonnegut’s education was interrupted by Prohibition and the Great Depression. Prohibition closed the brewery, and there were few new building projects during the Depression. His father withdrew into painting while his mother wrote unsuccessfully for popular magazines. Though he had started at a private school based on John Dewey’s ideas, Kurt was forced, due to the Depression, to attend public James Whitcomb Riley. He wrote for and was co-editor of the school newspaper, The Echo. Following graduation from Shortridge High in 1940, he started at Butler University and continued at Cornell, majoring in biochemistry, a practical but uncongenial field into which his father and brother had pushed him. He spent most of his time at Delta Upsilon fraternity and the Cornell Daily Sun, the university’s paper, where he was a writer and editor.

By spring 1942, Vonnegut, who was in ROTC, had forfeited his scholarship because of his Daily Sun articles. Placed on probation for poor grades, he dropped out and lost his deferment. In 1943, rather than being drafted, he enlisted. After basic instruction in howitzers and mechanical engineering, he was sent to Camp Atterbury, south of Indianapolis, for training as an intelligence scout. On a trip home for Mother’s Day, he learned his mother had killed herself with an overdose of sleeping pills and alcohol. Three months later, Vonnegut was on his way as an intelligence scout to the 106th Infantry, which had not yet seen battle. Then came the Battle of the Bulge, and Vonnegut was captured and shipped with the other men by cattle car to Dresden, where they would make a food supplement for pregnant German women.

Although Dresden didn’t have war industry, it was firebombed on February 13, 1945. The bombing drove firemen and emergency crews into shelters, and the incendiary bombs followed. Vonnegut was held with other prisoners three stories underground in Schlact Haus Funf (Slaughter House Five). When he came out, the city he had marveled at was gone. He and his fellow prisoners were put to work bringing out the bodies. While being moved as a result of Patton’s advance, they awoke one morning to find their guards gone. Mustered out, Vonnegut received a Purple Heart.

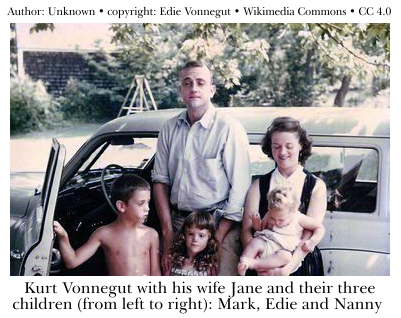

When Vonnegut returned from service, he married Jane Cox, his childhood sweetheart. They moved to Chicago, where he enrolled in a University of Chicago M.A. program and worked for the City News Bureau while Jane did graduate study in Russian literature. Pregnant with Mark, their first child (born 1947), Jane dropped out. When Kurt’s thesis wasn’t accepted, he also dropped out, though he had finished what would normally be an A.B. With his brother’s help, he got a publicity job with General Electric (GE) with the stipulation that he complete a degree. While working at GE, he was also a volunteer fireman in Alplaus, New York. Firemen later appeared as symbols of community in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Hocus Pocus. He also remembered the German firemen who were helpless as Dresden burned.

By 1949, the Vonneguts had another child, and in 1951, after publishing his first short story, Kurt left GE to write full time. After the couple moved to Cape Cod, he also served as a fireman and was active in the Barnstable Unitarian congregation. He helped with the “Every Member Canvas.”

During the early fifties, Vonnegut was writing stories for popular magazines known as “slicks” while working on his first novel, Player Piano. As television began to undermine the market for stories, he needed another way to make a living. He taught at a Cape Cod boarding school and wrote ad copy. With three children, he needed a steady income so in 1957 he made an ill-fated attempt to sell Saab automobiles. In October of that year his father died from lung cancer at 72. Rev. Jack Mendelsohn, the minister of All Souls Unitarian Church in Indianapolis, conducted the funeral service. All Souls claimed the elder Vonnegut as a member, and Mendelsohn named his own son for him. Later, Vonnegut Jr.’s son considered becoming a UU minister. All souls recognizes the author as a member on their web site.

The next year 1958 would bring both sadness and joy to the Vonnegut family. His sister, Alice, was hospitalized and dying of breast cancer in New Jersey when her husband, James Adams, was killed in a commuter train accident. Alice died the next day. Kurt and his wife took three of the four children, adopting James, Steven, Kurt, and their dogs, while the youngest, Peter, was taken by an Alabama cousin in an unpleasant family argument.

In 1959, though his family responsibilities had increased, Vonnegut completed his second book, The Sirens of Titan, in which he created the fictional Church of God the Completely Indifferent. The central doctrine of the church was that the meaning of life is not God. Free will doesn’t exist, and science has brought robots and catastrophe. Life is a series of accidents, and its meaning is “to love whoever is around to be loved.”

In 1960, Vonnegut was a Hugo Award finalist for best science fiction, and his play Penelope, about a soldier coming home from war, ran for six performances. He closed his Saab dealership, and twelve of his short stories were published as a collection, Canary in a Cat House. His third novel, Mother Night, about an imaginary WWII double agent, was accepted and published the following year. Another play, Who Am I this Time?, was at the Barnstable Comedy Club and would be revived after two years. Vonnegut was also at this time trying his hand at journalism with articles in Esquire, New York Times Book Review, and other places.

Cat’s Cradle came out in 1963 and was favorably reviewed by the British novelist Graham Greene. In Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut spins out his most elaborate fantasy religion on a mythical island called San Lorenzo. Reality is so awful that an imaginary religion is needed to distract people. Free will is abandoned for determinism: everything must be as it is. Only Humanity is holy. Bokononism, the religion, may be a useful lie, but it is better than science, which destroys the world with the fictitious Ice-9 that freezes everything it touches.

His next novel, published in 1965 and extensively reviewed, was God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, which dealt with the theme of a fool and his money. The giant computer in Player Piano had been asked what human purpose was, and Vonnegut was still pondering that question in this latest novel, where the ethical problem of technological society is “how to love people who have no use.” Foreshadowing Slaughter House Five, Eliot Rosewater has read about the bombing of Dresden and imagines Indianapolis in flames. He believes a new prophet is required to pull people back from the destruction caused by the misuse of science. This prophet will teach people how to care for and love one another. One is left, however, with the paradox that if Vonnegut really believes people are on a totally determined path, how can it be possible for them to change?

Despite the attention given to God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, Vonnegut still had to make a living. He accepted an invitation to teach at the famous Iowa Writer’s Workshop, in Iowa City. Upon arrival there, he wrote to his wife that he was attending a Unitarian Church nearby.

By 1967, Vonnegut had a new agent and was awarded a Guggenheim to work on the novel about Dresden. With support from the grant, he went to Dresden, after which he returned to the Cape. Welcome to the Monkey House, another collection of stories, came out that August.

At last, Vonnegut was able to write about Dresden in Slaughterhouse Five, which was reviewed on the front page of the NYT Book Review and was on the fiction list for sixteen weeks. The characters in the novel try to make sense of life against the background of war. After Dresden, Billy Pilgrim ends up in a mental hospital, where he meets novelist Kilgore Trout, who has written the Gospel from Outer Space, in which a Martian wonders why “Christians find it so easy to be cruel.” The novelist’s critique of the practice of Christianity does not mean, however, that he did not admire some Christians or that he reviled Christianity understood as a code of ethics rather than a divine revelation. Following the success of Slaughterhouse Five, Vonnegut was invited to teach at Harvard and went on to write Penelope, which became Happy Birthday, Wanda June, running for 96 performances on Broadway. During this time he and photographer Jill Kremetz formed a relationship, and he separated from his wife.

Both success and tragedy marked Vonnegut’s life. His son Mark, who had been living in a West Coast commune, had a manic breakdown, though he later recovered. Both of Mark’s grandmothers had emotional problems, and his mother also had had a very strange but less serious experience in 1958 that she compared with Mark’s breakdown.

On the success side, Vonnegut gave an address to the National Institute of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His wife Jane attended the event, and she and Kurt, arguing mostly about religion, tried unsuccessfully to reconcile. His beliefs didn’t change but Jane’s did. She became an Episcopalian, after exploring astrology, EST, Transcendental Meditation, and other belief systems. Kurt’s grandfather, Clemens, had presciently warned about the dangers of religious differences in marriage, but the author’s marital problems could have been caused in part by the bipolar illness for which he consulted a psychiatrist. He claimed to have a twenty day cycle that could have been inherited from his mother. There were also mental problems in his wife’s family.

Despite his marital problems and financial struggles, Vonnegut did not ignore social concerns. He donated money to Swarthmore College and the University of Chicago, as well as to Save the Children, the National Council of Negro Women, and the Unitarians. The University of Chicago finally granted him his degree on the basis of Cat’s Cradle (1971).

The following year, Breakfast of Champions, a novel focused on environmental crisis, was first on the best seller list for twenty-one weeks. In the book, artist Rabo Karakebekian claims that the light in his painting of St. Anthony is “the awareness” that human beings possess in contrast to the empty robot posited by the Kilgore Trout character. Kilgore Trout appears in several Vonnegut novels.

Honors were piling up for Vonnegut, but the critics didn’t find his work after Slaughterhouse Five to be as strong, though he continued to deal with important religious and philosophical themes. He became a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and received an honorary doctorate from Indiana University. Invited to teach at CUNY for a year, he formed a close friendship with fellow novelist Joseph Heller. In North Dakota and other states his work was censored but successfully defended by the ACLU. With his photographer companion, Jill Kremetz, he purchased and shared a New York City town house. At the end of that year, Jane reluctantly agreed to a divorce.

In 1974, Vonnegut published a collection of essays, speeches, and an autobiography called Wampaters, Fomas, & Granfalloons (Opinions). In an interview reprinted in that collection, he said, “I admire Christianity more than anything—Christianity as symbolized by gentle people sharing a common bowl.” He thought that too often religion was a cover for hypocrisy. His view of religion was pragmatic. What mattered was its usefulness in creating community and making people kind and helpful, contrasted to the illusory progress of science and technology.

The following year, he wrote Slapstick about the theme of loneliness. It contained another satire, The Church of Jesus Christ Kidnapped. While Slapstick wasn’t well received by reviewers, it was fourth on the New York Times‘ best sellers list.

As the 1970s drew to a close, his new novel Jailbird (1979) did better and was a number one best seller for five weeks. It was a commentary on Watergate, suffused with fatalism but inspired by the Sermon on the Mount. The protagonist, Starbuck, still believes that in spite of evidence for human depravity, people can be caring and kind. This contradiction between the novel’s fatalism and its advocacy of human effort is jarring. A musical of God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater was produced by his daughter Edie, and although the play did well, it closed for lack of a financial backer. He had hoped his second marriage to photographer Jill Kremetz would be in a Unitarian Church, but instead it was at Christ Church United Methodist in New York City on November 24, 1979.

In 1981, his “autobiographical collage,” Palm Sunday, appeared. It begins with a sermon. Vonnegut’s own first sermon, “Christ Worshiping Agnostic,” was given on January 27, 1980, at First Parish Unitarian Cambridge, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of American Unitarian founder William Ellery Channing. Vonnegut said, “… he had more trouble with the Trinity than college algebra.” The year ended with the novelist’s first art show in Greenwich Village.

In 1982, PBS American Playhouse adapted the short story “Who Am I This Time?” Vonnegut returned to the novel with Deadeye Dick, which made the best seller list for fourteen weeks. He had grown up with guns, but in the novel he attacks a violent culture and the drug industry that has a pill for everything.

By 1983, he was writing Galapagos, which had an evolutionary theme. The dangerous human species evolves into harmless animals losing their intelligence and kept in check by the natural balance of nature. It was published in 1985 following a suicide attempt on the 39th anniversary of the February 13th Dresden firebombing. Recovering, Vonnegut drafted a play and wrote Blue Beard about an abstract expressionist artist.

In 1986, Vonnegut was the Ware Lecturer at the Unitarian Universalist Association’s (UUA) annual General Assembly. His former wife, Jane Cox Yarmolinsky, who had married a defense spokesman and lawyer, died on December 19, 1987, from ovarian cancer. She left behind a memoir of their life together with the six children called Angels without Wings (1987). She felt Vonnegut had abandoned both her and the children. By 1988, in spite of everything, Vonnegut was back at work on a new novel, Hocus Pocus, about all sorts of contemporary social problems from higher education and intolerance to globalization.

In 1991, Vonnegut’s second wife, Jill Kremetz, sued for divorce, and he counter-sued for custody of their nine-year-old adopted daughter. Religious differences may again have played a role. Jill Kremetz was Episcopalian, as his first wife had been, and when their adopted daughter was baptized, he did not attend. According to Vonnegut, his wife thought he didn’t have a religion and was a “spiritual cripple.” He continued to say he was Unitarian Universalist since we accepted him. He was now living at the Long Island property. He and Jill didn’t reconcile, but the divorce was dropped. Putnam published his Fates Worse than Death: An Autobiographical Collage of the 1980s.

In 1992, Vonnegut was commissioned by The New York Philomusica Ensemble to write a libretto for Stravinsky’s 1918 L’Historie du Soldat. For inspiration, he turned to the story of Private Slovik, the only U.S. soldier executed for desertion since 1865. He was also chosen Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and was later appointed honorary president, a post he held until his death. In his role as president of an affiliated organization, his name appeared in the UUA directory.

Vonnegut’s creativity did not let up. Make up Your Mind was given an Off-Broadway performance in April and May of 1993, followed, a year later, by a world premier at Lincoln Center of the Stravinsky as L’Historie du Soldat /American Soldier’s Tale.

In 1995, he was at work on Timequake, dealing with free will and a Year 2000 space-time disaster that makes everyone relive the 1990s. His dissatisfaction with the book resulted in his rewriting and completing it the following year. He saw his completed version as partially autobiographical, mourning for his lost America. Whatever his doubts, the book was on the best seller list for five weeks. That year, he sold most of his papers, including manuscripts of his fourteen novels, to Indiana University’s Lilly Library.

On January 31, the millennium began with a fire in Vonnegut’s townhouse office caused by one of his Pall Malls. He often complained that the tobacco company had broken the promise on the package to kill him. Putting the fire out, he collapsed. His daughter Lilly and a neighbor dragged him out, and after two days unconscious and three weeks of recovery, his daughter Nanny convinced him to come to Northampton, Massachusetts, where he was settled in a small apartment not far from her family.

That spring, he was persuaded to join the Smith College English faculty, but a year later he had returned to his house on Long Island and started a novel. The tragedy of 9/11 broke his stride, and he put his writing in the drawer. He lent his name to an ACLU campaign against the Patriot Act.

Returning to writing, he did a new preface for a new edition of his son’s Eden Express and worked on his own novel, a satire of the Bush years called If God Were Alive Today. Interviewed by Joel Bleifuss of In These Times, he formed an alliance. He began to publish columns in the magazine using some of the material from the novel as well as other thoughts. The column was to be his last remaining literary activity. His 2005 short story, A Man without a Country, turned into a surprise best seller for six weeks. It revisited humanism and The Sermon on the Mount. In an interview in June of the following year, he said, “Everything I’ve done is in print. I have fulfilled my destiny, such as it is, and have nothing more to say. …I have reached what Nietzsche called: the melancholia of everything completed.’”

Death

In March 2007, Kurt Vonnegut fell and hit his head on the steps of his New York brownstone. In spite of efforts to save him, he died at the age of 84 on April 11. Mark, his doctor son, arranged a memorial service at the appropriately literary Algonquin. Mark was an active Unitarian, who had once wanted to be a Unitarian minister. Vonnegut’s seven children followed his will and scattered his ashes in Barnstable Harbor.

Sources

Kurt Vonnegut: Letters (2014) while Complete Stories (2017), edited by Dan Wakefield and Jerome Klinkowitz collects 98 Vonnegut’s short stories. Works with autobiographical elements include Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (1991), Palm Sunday (1984), and A Man Without A Country (2007). Vonnegut biographies include Ginger Strand, The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic (2015); Charles J. Shields, And So It Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life (2011); William Rodney Allen, Conversations With Kurt Vonnegut (1988); Jerome Klinkowitz, The Vonnegut Effect (2004); Mark Vonnegut, Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So (2010); Marc Leeds, The Vonnegut Encyclopedia (2016); and Loree Rackstraw, Love as Always Kurt: Vonnegut as I Knew Him (2009).

Vonnegut and religion are covered in three articles by Nicole Willett: “In Search of Soul,” in Harry Edwin Eiss, editor, Electric Sheep Slouching Towards Bethlehem: Speculative Fiction in a Post Modern World (2014); “If Jesus Did Stand-Up: The Comic Parables of Kurt Vonnegut,” in Studies in American Humor (2012); and “Vonnegut and Religion: Daydreaming About God” in Robert T. Tally, Jr., editor, Kurt Vonnegut: Critical Insights (2013). Also useful are Dan Wakefield,“Kurt Vonnegut: Christ-Loving Atheist” Image: Art, Faith, Mystery (Fall 2014); Chun-koong Han, “Kurt Vonnegut’s Humanistic Pessimism,” Journal of English Language and Literature (1995); and Peter A. Scholl, “Vonnegut’s Attack upon Christiandom,” Christianity and Literature (1972). The authorized Kurt Vonnegut website is vonnegut.com. You can visit the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library in Indianapolis, Indiana and you can rent the Clemens Vonnegut Jr. House on Lake Maxinkuckee. Wikipedia has a crowd sourced Kurt Vonnegut bibliography.

Article by Wesley V. Hromatko

Posted September 10, 2017