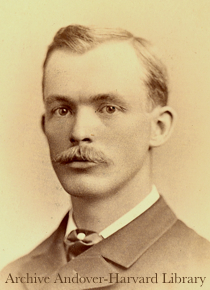

Rufus Austin White (Nov. 24, 1857 to July 25, 1937) was a Chicago minister active in charity, child welfare, education, and community affairs. Constrained by state and national Universalist Conventions, White and his congregation charted their own course under the name, People’s Liberal Church.

White was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania to Lucien and Caroline White. When he was seven, his father, a Union Soldier, was killed at Winchester, Virginia. Rufus prepared for college at Towanda, Pennsylvania, before entering Tufts College, where he graduated with a Ph. B. In 1884 he received his B.D. from Tufts Divinity School and in 1904, Tufts awarded him an honorary Sc. D.

White was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania to Lucien and Caroline White. When he was seven, his father, a Union Soldier, was killed at Winchester, Virginia. Rufus prepared for college at Towanda, Pennsylvania, before entering Tufts College, where he graduated with a Ph. B. In 1884 he received his B.D. from Tufts Divinity School and in 1904, Tufts awarded him an honorary Sc. D.

White’s first ministry was at the Newton Universalist Society in Newtonville, Massachusetts; 1884-1891. He married Louise E. Brooks of Boston in 1886 and they had two sons, Austin Goddard and Leslie Aldons.

When Florence Kollock, the minister at the First Universalist Church of Englewood, Illinois announced her resignation after 13 years of service, the congregation asked her to choose a replacement. She selected White. Englewood was annexed into Chicago in 1889 but the church and neighborhood retained the name.

In his first sermon in Englewood in February 1892,White set out his theology: Modernity demanded that the church be a social institution, where people could come together socially, find good books and listen to good music. It should be a place where members work together to solve the problem of poverty and thus gain the interest of those less fortunate in the spiritual guidance the church has to offer. White made no distinction between what was considered religious and what was considered secular: Doing anything that was good, he considered religious.

White published several of his sermons, including at least two that still exist. One was Hell: What Is It, and Where Is It? He believed the writers of the Bible did not identify hell as most people were taught to believe. “There is no theological hell of fire and eternal suffering,” White said, “There are, however, hells enough; hells where women are bought and sold under the stress of poverty. There are hells where children are damned into misfortunes, deformity of body and soul in the interest of profit. Evil abides, but we need no longer to fight some horned and cloven-footed devil of theology. The devil we need to fight is evil. The devil against which the modern church must fight is ignorance, greed, selfishness.”

The other surviving sermon is Salvation: Through Christ or Through Character. White wrote that salvation is earned by doing good deeds, by one’s character, not one’s religiosity or religious affiliation. The motto of White’s church was, “The union of all who love in the service of all who suffer and need help.” One of Dr. White’s favorite poems was Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s Which are You? Lifter or Leaner? White did not expect his parishioners to blindly accept his words of wisdom; after each service he would make himself available at “the fightin’ corner” where those who disagreed could debate with him.

The year after White arrived in Englewood, the 1893 World’s Colombian Exposition was held in Hyde Park about two miles east of his church while the World’s Parliament of Religions convened in downtown Chicago. The enthusiasm of the exposition and parliament were soon darkened, however, by widespread unemployment and unrest brought on by the Panic of 1893. The Pullman Strike in 1894, soiling the reputation of Universalist George Mortimer Pullman, took place a few miles south of the Englewood church.

White was elected secretary of the Chicago Liberal Ministers’ League, 1893; and to the 30 person board of the Congress of Liberal Religious Societies; 1894. The congress had members from Free Religious Association, Ethical Culture Society, and Jewish organizations. White supported extending membership to Theosophists, free thinkers and spiritualists.

Nominally Universalist, White and his Englewood congregation were a liberal group that participated in the activities of the Western Unitarian Conference (WUC), Jenkin Lloyd Jones’ Unity magazine, and Hiram Washington Thomas’ Fraternity of Liberal Churches. Like Thomas and Jones, White saw the west as a frontier brimming with opportunity compared to New England. Young ministers should go west rather than get their feet stuck in, “the tanglefoot paper of the Hub,” White said at an 1895 Boston convention of the Universalist Young People’s Christian Union.

White was a founder of the Chicago Bureau of Charities in 1896, which combined several local charities into one, eventually becoming the United Charities of Chicago. Based on the belief that poverty was caused by economic and social problems, not moral decay, the bureau provided services to the poor, not just money. While serving as president of the Illinois Children’s Home Society in 1887, he helped to consolidate it with the Chicago Children’s Aid Society to form the Illinois Children’s Home and Aid Society, which in 2010 was still headquartered in Chicago.

Working through the Civic Federation of Chicago, White started the Penny Savings Society to encourage school children to save their pennies, nickels and dimes by purchasing savings stamps at their schools. The stamps were affixed on cards to record savings in Northern Trust Company Bank accounts. Students saved over $300,000 between 1897 and 1905. In 1899, White, took part in the formation of the Central Anti-Imperialist League. Francis Ellingwood Abbot had started an anti-imperialist group in Boston the year before. Both groups opposed U.S. expansionist policies that followed the Spanish-American War.

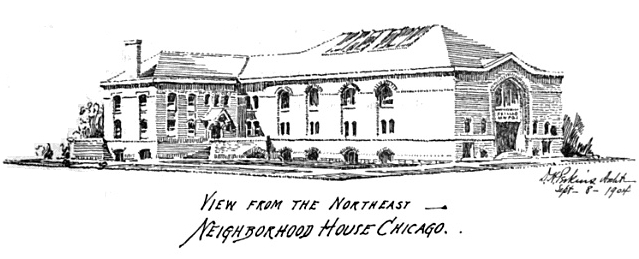

The Englewood Women’s Club in conjunction with the University of Chicago held lecture series and produced plays at the People’s Liberal Church starting in 1896. In 1900, White often preached on Sunday evenings at the People’s Church in Valparaiso, Indiana that had been started by Dr. H. W. Thomas of Chicago. The Englewood congregation also participated in the settlement house movement by supporting Neighborhood House at 67th and May Streets. It had been developed by the church’s Young People’s Society under the direction of Mrs. S. S. Van Der Vaart, 1901-05.

The Englewood Women’s Club in conjunction with the University of Chicago held lecture series and produced plays at the People’s Liberal Church starting in 1896. In 1900, White often preached on Sunday evenings at the People’s Church in Valparaiso, Indiana that had been started by Dr. H. W. Thomas of Chicago. The Englewood congregation also participated in the settlement house movement by supporting Neighborhood House at 67th and May Streets. It had been developed by the church’s Young People’s Society under the direction of Mrs. S. S. Van Der Vaart, 1901-05.

In 1904 White decided to leave the Universalist fold. The national Universalist General Convention had appended conditions of fellowship to the Winchester Profession while members of the Illinois Universalist Convention were criticizing his liberal views. The congregation voted to rename the church, the People’s Liberal Church in 1907. The Universalist Register continued listing the congregation and in 1912 it was listed as having 250 families and 500 members.

White supported Chicago’s union laborers. He opposed tailors having to work at home, “Men ought to have the enjoyment of their home life, without the specter of toil in it.” He supported shorter workday legislation saying, “The law might be so stringent in its regulations as to say we shall have eight hours for sleep, eight hours for play, and eight hours for work, and certainly eight hours is long enough for work.” He also spoke out against the importation of foreign laborers who would work for much lower wages.

White’s support for unions didn’t extend to women teachers. He was on the 21-member Chicago Board of Education, 1904-09; serving for a time alongside Jane Addams. White denounced the Chicago Teachers Federation (CTF) led by Margaret Haley and Catherine Goggin even though three-quarters of the elementary teachers in Chicago were members. They wanted equal pay, tenure, a paid school board, teacher pensions, and gender equity. He was opposed to teachers belonging to unions, supported a smaller paid board, supported higher pay for men, and wanted teacher pay to be based on tests and principal evaluations.

From 1905 to 1920, White traveled the world during the summers photographing and studying other cultures. In the winters he presented travel lectures accompanied by stereopticon slides at Chicago’s Medinah Temple (formerly Robert Collyer’s Church). Each lecture was presented on Sunday afternoon at Medinah Temple and on Sunday evening at People’s Liberal Church for three consecutive weeks. The Englewood church sanctuary was expanded to hold 750 people but people still were turned away. A new Medinah Temple seating 4,200 people was opened in 1912.

White, an accomplished orator, was famous in his day. Speaking on a platform with Booker T. Washington, he said, “We should not remain quiet and permit the South to undo that which was accomplished after a hard struggle nearly forty years ago. I do not advocate force to emphasize our views, but I do think the sentiment of the North should be united on this point, so that the South would treat the colored man more fairly.”

According to the Broad Ax, a black Chicago newspaper, White was the only white minister to deliver a sermon on race relations after the 1903 Belleville, Illinois lynching. “The men who lynched the Negro are like their own deed. They belong to the law-defying class. They have the hearts of savages and the cruelty of brutes,” he declared, “The lynchers of Belleville belong to the dark ages. They are a disgrace to our splendid law-abiding state of Illinois.”

Fifteen years after starting the Central Anti-Imperialist League, White came to terms with American expansionism and overseas possessions. Speaking to a group of engineers he said, “America has done more for the Philippines in the fifteen years of its occupation than proud Spain did for them in three hundred and thirty years.” For Philippine citizens “their fairest future, their largest opportunity, their certainty of safety will be under the American flag.” During World War I, White was appointed by President Wilson to be on the Chicago draft exemption board.

During the 1920s, White often spent his summers traveling aboard. He visited Europe, Japan and the Philippines before 1915; Cuba, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Argentine, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay, 1916; Great Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and Greece, 1919; and the British French Indies and Dutch West Indies, 1920. In addition to gathering material for his Stereopticon travel lectures, he was also a correspondent for the Chicago Daily Journal and wrote a children’s book, South America today: A travel book for boys and girls (1929). When radio became popular in the 1920’s, he broadcast his People’s Liberal Church sermons.

During the 1920s, White often spent his summers traveling aboard. He visited Europe, Japan and the Philippines before 1915; Cuba, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Argentine, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay, 1916; Great Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and Greece, 1919; and the British French Indies and Dutch West Indies, 1920. In addition to gathering material for his Stereopticon travel lectures, he was also a correspondent for the Chicago Daily Journal and wrote a children’s book, South America today: A travel book for boys and girls (1929). When radio became popular in the 1920’s, he broadcast his People’s Liberal Church sermons.

To honor White’s 25 years of service at Englewood, the congregation decided to take on a worthy project, the Oakhaven Old People’s Home. By holding dinners and bazaars, church members raised $60,000. In 1923 when White learned that the $1.75 million estate of Emilie Smith was available to a suitable charity, he obtained it for Oakhaven. In honor of Emilie’s parents, it was renamed the Washington and Jane Smith Home. Now called Smith Village, it is one of the nation’s premiere retirement homes.

White retired from the pulpit in 1936. Less than a year later he died. Services were held at the Englewood Masonic Temple. After his death, Unitarian minister Preston Bradley and Charles H. Lyttle of the Meadville-Lombard Theological School advised the congregation to join the American Unitarian Association. So they did. In 1951 People’s Liberal Church merged with the Beverly Unitarian Fellowship and in 1957 it was renamed Beverly Unitarian Church.

Information on Rufus A. White is in the archives of Beverly Unitarian Church (BUC), Ridge Historical Society, Smith Village, and the Scottish Rite Body – Valley of Chicago. A rich source in the BUC archives are the notes, letters and documents collected by Vincent B. Silliman to prepare,The Present and the Days that Were: A Sermon Reviewing and Interpreting the History of More than Eighty Years of The Beverly Unitarian Church (1958). The BUC archives also contain the notes and letters of Clara Nieburger and a scrapbook by Eugenie F. Morgan (1906). Newspaper articles by or about White are in the Chicago Daily Tribune, Chicago Daily News, Southtown Suburbanite, Southtown Economist, Chicago Broad ax, and the Blue-grass blade (Lexington, Ky.). Information on White and the Western Unitarian Association can be found in Charles H. Lyttle, Freedom Moves West (1952); Charles A. Howe, The Larger Faith (1993); Charles W. Wendte, Freedom and Fellowship in Religion: Proceedings and papers of the Fourth International Congress of Religious Liberals (1907); and Mark W. Harris, The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism (2004). Chicago school board and Chicago Teachers Federation battles are detailed in Kate Rousmaniere, Citizen teacher: the life and leadership of Margaret Haley (2005). Information on travel and passports was accessed at ancestry.com.

White is mentioned in four newsletters: The Reminder, Bethany Union Church; Onward, Young People’s Christian Union; The Messenger, People’s Liberal Church; and Universalist Messenger, Illinois Universalist Convention. Useful periodical include: Unity; The Expositor and current anecdotes; The Tailor: official organ of the Journeymen Tailors’ National Union; Cigar Makers’ Official Journal; and the Educational review, Nicholas Murray Butler, ed.

Writings by White include, “Our Work in the West,” in Our Word and Work for Missions, Henry W. Rugg, ed. (1894), the “McKinley memorial address,” in Freethought Magazine, H. L. Green, ed. (1901); “The Philippines,” in The Journal of the Western Society of Engineers (1915); and two published sermons.

Article by Errol Magidson

Posted June 28, 2011