John Bird Wilkins (ca 1849-1938) was a minister, teacher, inventor, and newspaperman. For a year or two he was a Unitarian minister. Little is known of his early life; no birth date, no mother’s name, no father’s name, no school records, and no places of residence. He was probably born into slavery in Mississippi before the Civil War when official records for blacks were unknown and personal records were often lost as family members were bought, sold, and separated. Most of the details of his early family life and education are either tentative or non-existent.

John Bird Wilkins (ca 1849-1938) was a minister, teacher, inventor, and newspaperman. For a year or two he was a Unitarian minister. Little is known of his early life; no birth date, no mother’s name, no father’s name, no school records, and no places of residence. He was probably born into slavery in Mississippi before the Civil War when official records for blacks were unknown and personal records were often lost as family members were bought, sold, and separated. Most of the details of his early family life and education are either tentative or non-existent.

We know he moved north after the Civil War because he opened a bank account at the Freedman’s Bank in Memphis, Tennessee in 1873. The next year he deposited money in the same bank acting as the secretary of King Solomon Lodge Number Two of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons. Four years later he was listed as “John B. Wilkins (colored), teacher,” in the 1878 Memphis city directory.

After another gap, this time seven years, Wilkins is in Farmington, Missouri. In January 1885, he organized a group called the Colored Working Men’s Association. The group raised funds and built Colored Hall, which became the home for many of the town’s black religious and fraternal groups, including the Prince Hall Masons and the Black Knights of Pythias. He also met Susan Douthit in Farmington. Her father Hilliard was a member of the Prince Hall Masons.

Wilkins was in St. Paul, Minnesota a few months later according to an article in the Western Appeal, a newspaper serving the Chicago and Twin Cities black communities. The paper reported that Rev. Byrd Wilkins was duly installed on June 21, 1885 as the pastor of the Pilgrim Baptist church. He delivered an “eloquent discourse,” based on Psalm 120:1, “In my distress I called unto the Lord, and he heard me.” The church had been founded in 1863 by black “pilgrims” who had escaped from Boone County, Missouri with the aid of Union troops and the Underground Railroad. In July, Wilkins was sworn in as the President of the Excelsior Literary Society which also met at the church. In December, Wilkins spoke to “The colored citizens of Minneapolis,” according to an article in the St. Paul Daily Globe. The assembly developed plans to celebrate the emancipation of slaves on New Year’s day. A week later the Globe printed a good portion of his Sunday sermon.

Over the next two years, Wilkins was often at the center of activities in St. Paul’s small (500-600) black community. He helped organize the St. Paul Colored Citizens’ Club and was elected its first president, he was the President of the Robert Elliot Club when they held a celebration in honor of the fifty-second anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the West Indies, and he assisted John Q. Adams, the editor of the Western Appeal in the formation of the Young Men’s Republican Club.

On Sunday morning, November 28, 1886, his sermon was on “The Increase of the Church,” while his evening topic addressed “The Rationality of Religion.” Three months later he preached against “high license,” the imposition of steep liquor taxes and fees, because “it simply means crush the poor man and let the rich men make the money.” In April 1887, the Western Appeal reported that they had received the first issue of a new quarterly magazine, Pulpit and Desk. Edited and published by Wilkins, “. . . it contains a number of the sermons and addresses of the editor, and several articles from other noteworthy writers.”

On March 5, 1887, the Rev. Bird Wilkins was called to preach at the Bethesda Baptist Church in Chicago, Illinois. The family left St. Paul six weeks later. A son Charles had been born to Wilkins and Susan Douthit during their time in St. Paul. Another son was born in Chicago that September.

Wilkins was well received in Chicago. The Chicago Daily Inter Ocean called Wilkins “the most eloquent colored preacher in America to-day.” According to the Western Appeal, “He proposed to preach a religion of joy and gladness, and not one bit sorrow and tears.” The Chicago Tribune, reported that Wilkins, “. . . does not believe in future punishment by fire and brimstone, and says he ‘would rather preach no God at all than to preach that my God does all the dire, and dirty, and mean things some preachers say he does.’” The Chicago Herald reported him saying, “It is no advantage to the religion of Christ or the Church that law are being enacted at our State capital to enforce the observance of Sunday.” An August headline in the Chicago Tribune read, “A Remarkable Sermon: The Rev. Bird Wilkins likens Henry George to Christ.”

The 1880s were a time of change for Chicago. Labor was struggling for its fair share. The population of the city doubled from a half million to a million. There were 6,500 blacks residents at the beginning of the decade and 14,200 at the end. When street car workers went on strike in 1885, Mayor Carter Harrison said, “Nine out of every ten citizens were with the strikers.” In 1886 workers called a general strike for the eight-hour day, police shot six workers at the McCormick works, then a bomb exploded the next day during a peaceful demonstration in the Haymarket. The ensuing conspiracy trial split Chicago along class lines, drew worldwide attention to the Haymarket Affair, and fed a decade-long frenzy of labor-capital bombast.

It was also a decade when Chicago’s black elite were striving for intellectual and social refinement. Speaking German was a mark of culture that

Fannie Barrier Williams, one of Chicago’s black leaders sought to master. Fannie and her husband led the Prudence Crandall Study Club where Jenkin Lloyd Jones presented a program on the great paintings of the world. Meanwhile, Jones announced that his church, All Souls Unitarian in Chicago would welcome African American members. Sociologist St. Clair Drake would later coin the term Afro-Saxon to describe this pursuit of high European culture by the black elite of the time.

Then trouble started. Wilkins received an anonymous letter warning him to stop having open communion. Members of his congregation were upset and on September 5th, he resigned his position at Bethesda Baptist church after preaching for only six months. On October 15th, the Western Appeal reported that Wilkins was going to establish a new non creed liberal church to be known as the “Peoples Temple.” The same day the Western Unitarian weekly newspaper, Unity, carried a long review of Wilkins first service:

Notes from the Field

Chicago.—Freiberg’s opera house on Twenty-second street, between State street and Wabash avenue, was the scene last Sunday of an event important and novel,—nothing less than the inaugural meeting of the first African Unitarian society in the world. Rev. Bird Wilkins, a young colored preacher, who came to Chicago about two years ago as pastor of the Bethesda Baptist church, has worked his way out of the popular theology, and carried the bulk of his congregation with him.

A few weeks ago some dissension was stirred up in that church by the efforts of influential Baptists on the outside, and Mr. Wilkins wisely chose the independent course of resigning his pastorate. Three-fourths of the members of his church have followed him, and the attendance last Sunday afternoon included over a hundred of his own people, with a sprinkling of sympathizing friends from the various Unitarian churches of the city. The principal address was delivered by Rev. James Vila Blake, who stated with depth and comprehensiveness, as well as earnestness and simplicity, the leading principles of the new faith to which the people before him are aspiring.

Rev. David Utter followed with a few well-chosen words of sound advice, after which Mr. Wilkins read the articles of fellowship of the new church, which were stated in language taken substantially from the resolutions passed last May by the Western Unitarian Conference. He also read letters of sympathy and encouragement from Mrs. Prudence Crandall, Rev. Thomas G. Milsted and others. The outlook of the new movement seems most encouraging, and it starts out with the full sympathy and co-operation of the Unitarians of Chicago. We shall hope to give further news of Mr. Wilkins and his church ere long.

A week later Unity reported that the “Rev. Bird Wilkins, of the new liberal movement among the colored people, and Rev. Eliza T. Wilkes,” had attended James Vila Blake’s noon Sunday school teachers’ meeting. A month after that the Unity article was reprinted in the British Unitarian magazine, The Christian Life.

The 1880s were a decade of dissension among Unitarian factions. The more liberal ministers were joining the Free Religious Association (FRA) led by William James Potter. The split between conservatives and liberals widened at the 1886 Western Unitarian Conference meeting in Cincinnati, Ohio when Christian theists Jabez Thomas Sunderland and Brooke Herford disparaged liberals Jenkin Lloyd Jones, William Channing Gannett, and James Vila Blake as skeptics and agnostics.

In December of 1887, Unity reported that the People’s Temple Church (colored Unitarian) had secured permanent quarters at 2906 State street, where regular Sunday services would be held at 11 a.m. and 7:45 p.m. Chicago Unitarians, the Western Unitarian Conference, and Unity magazine supported the new group. A Unity article that December said:

Notes From the Field

Chicago.—The new movement of the colored people, under the name of the Temple church, really the Fifth Unitarian Church of Chicago, seems to be moving quietly on to success. Plans are already made and published for a sensible church building, with interesting accessories, which, in addition to the land, will cost $30,000, and we understand one-half of the money is already subscribed.

Members of this society gave a pleasing concert on Friday evening, December 2, at the Third Unitarian church, in the interests of this building fund, and the concert was repeated at All Souls church on Wednesday evening last. It can not be mentioned in these columns this week, but Mr. Blake wrote of their last week’s performance: “We had a charming evening with our friends of the Fifth Unitarian church, and the first African Unitarian church in the world. They gave us an admirable concert. Our people were greatly pleased with it and with them as well as their performance, and gave them a warm personal greeting afterward. You will be charmed with their entertainment and their presence.”

The Conservator, a newspaper for Chicago’s black community wasn’t as positive as the Unity magazine author. An article by the “Squire” said, “Bro. Wilkins is a man of considerable intelligence, but he is a great schemer, and the best laid plans of mice and men gang oft aglee.” In January 1888, Wilkins received a second warning letter signed ORTHODOX, accusing him of “teaching religion from the devil,” and threatening to burn his house down and kill him. Here’s the story from the St. Paul Daily Globe of January 7, 1888:

REV. BIRD WILKINS

Encounters People With Unchristian Attributes in His New Field.

Rev. Bird Wilkins, who went to Chicago from St. Paul a short time since, has encountered a world of trouble. Mr. Wilkins took charge of a prosperous Baptist church, but he had some trouble with his deacons, and, after several weeks of trouble, severed his connection with the church and started a new one on broader and more liberal grounds, taking with him nearly half the members of his former congregation. Ever since the trouble culminated in his leaving and starting a new church, he has been subjected to numerous annoyances from some person unknown, but presumably belonging to the old church organization. Threatening letters have been sent to him telling him that he had better leave the city; that he would not be permitted to preach, and if he did not cease in his endeavor to organize a new church he would regret it.

The story of Wilkins Unitarian ministry is mostly lost after the middle of 1888. Before disappearing from the record, Wilkins was granted fellowship by the Unitarians. A short article appeared in The Unitarian: A monthly Magazine of Liberal Christianity:

Notes From the Field

This is to certify that the Rev. Bird Wilkins, recently of the Baptist denomination and pastor of the Bethesda Baptist Church of Chicago, has applied for fellowship in the Unitarian denomination. We have examined his credentials and recommend him to the favor and fellowship of our ministers and churches.

February 1, 1888

John R. Effinger,

John C. Learned,

J. T. Sunderland,

Western Committee of Fellowship.

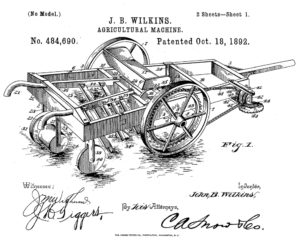

Wilkins left Chicago sometime during 1888. No records have turned up to tell the story of the dissolution of The People’s Temple congregation. Susan Douthit and John Bird Wilkins had two children in Farmington, Missouri; Aravelle in 1889 and Mary Corinne in 1891. Wilkins busied himself with a new career as an inventor. The Western Appeal for May 16, 1891 reported that he had obtained a patent on a type-setting machine and sold one-fourth of the rights for $150,000. The next year he obtained a patent for an “Agricultural Machine.” It was a convertible unit that served as a turning plow, shovel plow, harrow, seed sower, drill, corn planter, cotton cultivator and stack cutter. When you removed two bolts, it could be converted into a road-cart, dump-cart and market wagon. Wilkins assigned half of the patent to Thomas W. Stringer of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Stringer, the first black man elected to the Mississippi State Legislature in 1870 was also the founder of the T. W. Stringer Masonic Lodge.

In Farmington, Wilkins became involved with Lena Murphy. They moved to Little Rock, Arkansas where Lena gave birth to a son that John Bird named Edward Everett Wilkins. Back in Missouri, Susie Douthit gave birth to another son, Jesse Ernest Wilkins, in 1894. Wilkins had seventeen children in all.

After working as a laborer for a number of years in Arkansas, John Bird Wilkins and Lena Murphy moved to St. Louis around 1915. He joined the “Committee of 100” to support the war effort and he returned to editing with work at the St. Louis Clarion, another African American newspaper. In the 1920s, he started the Business Men’s Bible Training School in St. Louis. There is no record that he ever worked as a minister again, but he did preach a sermon on “Religion is Love,” at a Cairo, Illinois church in 1921. He also returned to Chicago in 1927 to preach at the 40th anniversary of Bethesda Baptist Church.

Death

John Bird Wilkins died in 1938. In 1954, his son, J. Ernest Wilkins was appointed Undersecretary of Labor by Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was the first black to attend a White House cabinet meeting. In 1958, J. Ernest was appointed to the newly created U. S. Civil Rights Commission.

Sources

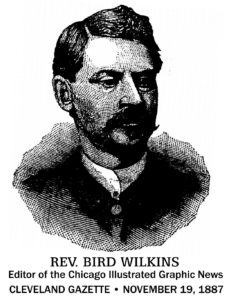

A number of black newspapers were started in the years after the close of the Civil War. John Bird Wilkins is mentioned a number of times in the Western Appeal (later shortened to The Appeal) published in St. Paul, Minnesota. The Cleveland Gazette has a short article and the only image of Wilkins. The St. Paul Daily Globe also covered him extensively. All three of these papers can be accessed at the Library of Congress website in the Chronicling America collection. References in Unity, The Christian Life (United Kingdom), and The Unitarian can be accessed using Google Books and/or at HathiTrust.org. The exhaustive biography of Wilkins written by his great-granddaughter, Carolyn Marie Wilkins, Damn Near White: An African American Family’s Rise from Slavery to Bittersweet Success (2010), is the only biography. It combines detailed genealogical research, information from hundreds of archival documents, interviews with family members, newspaper articles, and city directory listings to recreate his life. An extensive bibliography of primary and secondary sources is included.

Wilkins is mentioned in St. Clair Drake’s Works Progress Administration (WPA ) booklet, Churches and voluntary associations in the Chicago Negro Community, (1940). Wilkins is also covered in Christopher Robert Reed, Black Chicago’s First Century: Volume 1, 1833-1900 (2005). Reed’s book is also valuable for its comprehensive look at the history of black churches and culture during the period. See David Vassar Taylor, “The Blacks,” in June D. Holmquist, ed., They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups (1981) for a through history of African Americans in the Twin Cities. A good overview of the ferment and controversy between eastern and western Unitarians and the influence of the Free Religious Association (FRA) on that controversy can be found in the opening chapters of Allen Ruff, We Called Each Other Comrade: Charles H. Kerr & Company, Radical Publishers (1997). Also useful is Charles H. Lyttle, Freedom Moves West: A History of the Western Unitarian Conference, 1852-1952, (1952 & 2006).

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted September 15, 2013