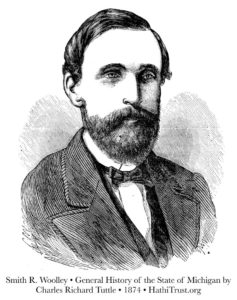

Smith Rensselaer Woolley

Smith Rensselaer Woolley (1840-March 7, 1886) was the son of Universalist minister Edward Mott Woolley and the brother of Lucia Fidelia Woolley Gillette, one of the first women ordained to the Universalist ministry. He was the father of Clarence Mott Woolley, a trustee and benefactor of St. Lawrence University, a school associated with the Universalist denomination. Smith Rensselaer Woolley and his family attended the Unitarian church in Detroit, Michigan.

Born in Bridgewater, New York in 1840, the youngest son of Laura Smith and Edward Mott Woolley, he was named for Universalist circuit riding preacher Stephen Rensselaer Smith, a friend and mentor of his father. When he was seven, the Woolley family moved to a frontier home near Birmingham, Michigan. His parents divorced in 1850 and his mother moved back to Nelson, New York to live with her family. He stayed in Michigan with his father. Three years later his father passed away.

On his own in frontier Michigan, Woolley worked hard, Horatio Alger fashion, to rise from rags-to-riches. He assisted his older brother Edward Jackson Woolley selling locks and safes as agents for Lillie’s Fire and Burglar Proof Safes. In 1854, he took a position with a Detroit banking house, C. & A. Ives, where he stayed for ten years.

Woolley married Maria Richardson Smith in 1860 and they had two sons, Clarence Mott Woolley and Elijah Smith Woolley. He was elected to the Detroit common council in 1871, served on the school board, and was active in the Detroit stock exchange and the board of trade. His wife represented the Detroit Unitarian Church on the Executive Committee of the Detroit Industrial School and they both supported the work of the Detroit Relief and Aid Society.

He started a distillery in 1868; advertising distilling alcohol, cologne, and vinegar. By 1874 Woolley was operating one of the largest distilleries in the west. According to the Detroit Free Press, he was distilling 10 barrels of whiskey a day and paying the federal government $575 a day to purchase the requisite alcohol tax stamps.

Woolley lost his fortune in the long depression that followed the panic of 1873. He filed for bankruptcy in 1878. Afterward, in 1882, he was appointed actuary for the Commercial Mutual Association. The next year he wrote the popular S. R. Woolley’s Practical Bookkeeping (1883). He died in 1886 when he was 47 years old.

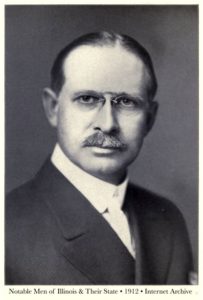

Clarence Mott Woolley

Clarence Mott Woolley (September 15, 1863-July 18, 1956), a prominent twentieth-century industrialist, worked with J. P. Morgan to build the American Radiator Company into a worldwide conglomerate that monopolized the home and commercial heating markets. Business biographies mention that he was a Unitarian, but he should also be remembered as a benefactor and trustee of St. Lawrence University, a Universalist institution. He was a close friend of Universalist businessman Owen D. Young, another St. Lawrence supporter. They served together on the board of New York Federal Reserve, corporate boards, and government commissions. Recent business historians have compared the power and influence of Young and Woolley in the early twentieth-century to that of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs at the beginning of the twentieth-first.

Clarence Mott Woolley was the son of Maria Richardson Smith and Smith Rensselaer Woolley, a Detroit businessman and banker. He was the grandson of Universalist minister Edward Mott Woolley and the nephew of Lucia Fidelia Woolley Gillette, one of the first women ordained to the Universalist ministry.

One popular biography of Clarence Mott Woolley echoes the same Horatio Alger rags-to-riches narrative that his father’s biographers had used; “Forced to begin working at the age of 15 after the panic of 1873 wiped out his father’s fortune, Woolley by 1886 had become a successful salesman of wholesale crockery and had built personal savings of around $5,000, not an insignificant amount of money at that time.” It also reports that he was attending a private grammar school where he was being groomed to attend Andover and Yale, but the depression of 1873 forced his parents to move him to a public school. The biography goes on to say that, “When his father died several years later, 15-year-old Clarence quit school all together to find work.”

In 1887 Woolley joined the Michigan Radiator & Iron Company of Detroit, makers of cast iron radiators for residential and commercial heating systems as head of sales. By 1892 he was general manager of Michigan Radiator and he played an instrumental role in the acquisition of two other manufacturers of cast iron radiators, Detroit Radiator Company and the Pierce Steam Heating Company of Buffalo, New York. The new firm, American Radiator Company (ARCo), was headquartered in Chicago, Illinois with Woolley as secretary.

The adoption of radiators and elevators paved the way for taller buildings so radiator sales grew rapidly until slowed by the panic of 1893. After talking with Europeans attending the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, Woolley went on a sales trip to Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, and France. A large order for the new Swiss capital building helped save ARCo from bankruptcy. In 1897 American Radiator obtained a manufacturing subsidiary in England when they purchased the Ideal Boiler Company. The following year the company set up a subsidiary in France. J. P. Morgan, the American financier worked with ARCo management to consolidate most of the radiator manufacturers in the United States in 1899. Woolley was appointed president of the American Radiator in 1902.

Woolley enjoyed travel, art, music, and architecture. He had subscribed to the Detroit Institute of Arts “$100,000 fund” in 1891. In Chicago, he was an early supporter of Poetry Magazine and he started collecting paintings and furniture. He married Harriet Paulina Hale in 1897 in Chicago. They had no children. Both were accomplished musicians and active in Chicago society. He subscribed to the Chicago symphony building fund and then served as a trustee of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 1905-1918. He held memberships in numerous clubs including the Chicago Club, Chicago Athletic, Chicago Golf, Exmoor, Onwentsia, Saddle and Cycle, and the South Shore Country Club. He was also a member of the Chicago Field Museum and the Chicago Industrial Club, later renamed the Commercial Club of Chicago.

When Harriet and Clarence separated in 1912, she went to Baden Baden, Germany with her maid. The Woolleys were granted a divorce by a Parisian tribunal the following year. When a Chicago Tribune reporter inquired about Harriet, Woolley’s mother said, “She’s an extravagant, wasteful woman, and my boy has been indulgent.” After World War I, Harriet lived in a villa near Florence, Italy. When she died in 1929, she bequeathed a half-million dollars to the University of Paris for scholarships.

Woolley married a second time to Isabelle McKindley Baker of Nashville, Tennessee. The couple settled in New York City where they had three children. In the 1920s they moved to Sunridge Farm, a 22-acre estate near Greenwich, Connecticut.

During World War I, ARCo plants in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Belgium were in the hands of the Central Powers: American plants switched to producing guns and grenades. During the war Woolley helped found the Institute of Thermal Research to explore alternate fuels and improved heating designs. In 1917 President Woodrow Wilson appointed him vice chair of the War Trade Board to oversee imports and exports. John Foster Dulles was secretary of the board.

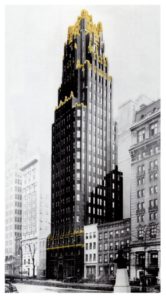

After the war, ARCo recovered its foreign possessions and a post-war boom in U.S. construction revitalized the business. Woolley commissioned architect Raymond Hood to design a corporate headquarters building in New York City. The 21-story Radiator Building opened in 1924. A striking building of black and gold, Georgia O’Keeffe did a painting, “Radiator Building at Night,” of the new headquarters in 1927.

In the 1920s, Woolley attempted to merge ARCo with Johns-Manville, Standard Sanitary, and Otis Elevator companies. That four-way deal faltered but Standard Sanitary and ARCo continued negotiations, merging in March 1929 just six months before the stock market crashed and the Great Depression started. The new company, which had netted $20 million in 1929, lost $6 million in its worst depression year, 1932. Then New Deal construction stimulus policies increased sales. In 1934 Woolley shocked his capitalist cronies saying, “I have always been a rank Republican, but I take my hat off to President Roosevelt. The administration has performed a miracle . . .”

Clarence Mott Woolley was a member of the American Academy of Political and Social Science; the Pan-American Society; American Chamber of Commerce in France; the British Chamber of Commerce; the Pilgrims Society—a trans-Atlantic group promoting British American ties; the Economic Club of New York; and many other groups. He served as a director for the Council on Foreign Relations, 1932-35; and was a director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1921-36. Woolley served on corporate boards at General Motors; Hotel Waldorf Astoria; Gold Dust Corporation; General Electric, Atlantic Mutual Insurance; First National Bank of Chicago; Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway; Continental Insurance; Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad; Mutual Life Insurance; and Texas Gulf Sulphur. He was also an incorporator and director of the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Woolley was appointed to the board of Columbia University in 1931 and he served on the Board of Trustees of St. Lawrence University, 1931-47. His friend, Universalist industrialist and St. Lawrence University graduate Owen D. Young had joined the St. Lawrence board in 1912 and served as board president starting in 1924. Young—founder of the Radio Corporation of America—served on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1923-40, while Woolley was a New York Fed director, 1921-36. The two also served together on the board of General Motors. Young was outgoing and public while Woolley was taciturn and private. Time Magazine called Woolley “One of Manhattan’s least-known tycoons. . .”

At the St. Lawrence University commencement in 1931, the university gave honorary degrees to Clarence Mott Woolley; Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon; Andrew’s brother Richard B. Mellon; and Unitarian minister and commencement speaker, John Haynes Holmes. Afterwards a new men’s dormitory was dedicated. The Mellons along with Owen D. Young and George F. Baker were major cash donors for the dormitory while Woolley provided the heating equipment for the building.

Woolley House at Bennington College in Vermont was named for his wife Isabelle, honoring her role in the founding of Bennington College in 1932. In 1935 the Woolley’s hosted Salvador Dali at Sunridge Farm, their home in Greenwich, Connecticut. Afterwards Dali presented Woolley with a portrait of his wife Isabelle. The Woolleys also entertained Arturo Toscanni for six weeks while he was conducting a series of symphonic recordings. At the beginning of the twentieth-century, Woolley had bought the 140-acre La Mesita Ranch near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Horses were integral to the ranch so a polo field—reputed to be the first in the west—was built at La Mesita. In the 1930s Woolley hired the renowned Santa Fe architect John Gaw Meem to oversee the design and construction of three homes on the ranch property.

Woolley retired in 1938 following a hostile takeover attempt. Tragedy struck the following year when his 22-year-old son, Clarence Mott Woolley, Jr., a star on the Yale University polo team, died from a concussion after falling off his pony. The Woolley family set up a memorial fund in his honor to benefit students in Yale’s Timothy Dwight College. Woolley had mixed feeling about his daughter, Doriane; when she was in college he referred to her as a “limousine-type radical.” After graduating from Bennington College she went on to do graduate work at Columbia University. Then working with the noted ethnomusicologist George Herzog, she did field-recordings of Pima Indian songs. John Carrington, his other son served in World War II as a counter-intelligence agent and then settled in the Santa Fe, New Mexico area where he was active in community affairs. The Woolley family held on to the La Mesita ranch until 1959, then in 2008, La Mesita returned to the Pueblo of Pojoaque Tribal Land Trust.

In his last years Woolley divided his time between Laguna Beach and Palm Springs, California. He died in 1956 and was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit, Michigan. Four educational institutions and the non-denominational Community Church of Palm Springs, California were among the beneficiaries of his $750,000 estate.

Sources

A short biography of Smith Rensselaer Woolley is in Charles R. Tuttle, General history of the state of Michigan: with biographical sketches, portrait engravings, and numerous illustrations (1873). Back issues of the Detroit Free Press available at newspapers.com, have additional information and an obituary for Smith Rensselaer Woolley.

No archival repositories of Clarence Mott Woolley papers have been found. Chapter-length articles on management written by Woolley are in The Business Man’s Library (1908-1917) and they can be accessed on-line using the HathiTrust.org or Google Books libraries.The most extensive source of biographical information is found in the American Standard corporate history by Jeffery L. Rodengen, The History of American Standard (1999). Also useful are Milton Moskowitz, Everybody’s Business (1990); Anthony J. Mayo and Nitin Nohria, In Their Time: The Greatest Business Leaders of the Twentieth-Century (2005); and John N. Ingham, Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders (1983). Also useful are articles in Fortune Magazine (April 1935) and Time Magazine (Nov 28, 1938). Additional family and business coverage can be found in the Detroit Free Press, Chicago Tribune, and the New York Times.

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted March 17, 2016