Lucia Fidelia Woolley Gillette (April 8, 1827-October 14, 1905) was one of the first women to be ordained to the Universalist ministry in the United States and probably the first ordained woman to preach in Canada. As a child she assisted her father, Edward Mott Woolley as he traveled his Universalist ministry circuit in New York. By her teen years she was writing for Universalist newspapers and journals, and later in life she campaigned for woman’s suffrage and lectured on religious, literary, and women’s issues. Her writing often reflected the concerns of her era; family, death, children, and Universalism’s promise of heavenly reunion.

Lucia Fidelia Woolley Gillette (April 8, 1827-October 14, 1905) was one of the first women to be ordained to the Universalist ministry in the United States and probably the first ordained woman to preach in Canada. As a child she assisted her father, Edward Mott Woolley as he traveled his Universalist ministry circuit in New York. By her teen years she was writing for Universalist newspapers and journals, and later in life she campaigned for woman’s suffrage and lectured on religious, literary, and women’s issues. Her writing often reflected the concerns of her era; family, death, children, and Universalism’s promise of heavenly reunion.

Born in Nelson, New York to Laura Smith and Edward Mott Woolley, she was the oldest of seven children. Her father was a shoemaker who had been raised a Quaker, but joined the Presbyterian Church a few years before Fidelia was born. During her first years, the family moved around central New York. They lived on her grandparent’s retirement farm in Cazenovia for two years before moving to Munnsville where her father opened his own leather shop. As he worked in his shop he was also studying religion under the mentorship of Universalist circuit-riding ministers John Freeman, David Biddlecorn, and Stephen Rensselaer Smith. The whole family would attend when one of them preached nearby.

During the Panic of 1837 her father suffered reverses, so they moved back to the grandparent’s Cazenovia farm. Then in 1841 her father was called to the Universalist ministry in Bridgewater, New York. On alternate weeks he would preach in Lebanon, New York. Fidelia often accompanied her father on his ministerial rounds. When his tuberculosis left him tired and weak, she would take the reins of the horse and buggy so he could rest or work on sermons. At home, “I was always on my low seat at his feet,” Fidelia wrote, “when I could be released from the care of my young brothers and sisters . . . .” She learned to read at a very young age, and it wasn’t long before she was reading her father’s scholarly books, Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, and Universalist periodicals. In the habit of singing her thoughts and then writing them down, she always carried paper and pencil. After elementary school Fidelia attended the Cazenovia seminary and then the Bridgewater academy. Her story “Old School Days,” probably reflects her own school experience.

Judging by her published works, Fidelia received an excellent education. The June 1847 edition of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate contains an accomplished essay by Fidelia titled, “Truth and Right.” It is signed with her pen name, “Lyra, Bridgewater, N. Y.” This early work shows a very capable writer and poet discussing science, faith, and the search for truth.

As a teenager, Fidelia was close to Universalist poet and author Laura Eggleston who was fifteen years older; they read and published in the same Universalist periodicals. Poems and stories by Eggleston, over the pen name “Lita,” first appeared in the 1830s and 40s. Later, these journals would carry Fidelia’s poems and stories, usually under the pen name, “Lyra.” A poem of farewell, “To Lyra” from “Lita,” in the March 1847 Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate lists the Clinton Liberal Institute as “Lita’s” location. The poem “A Response,” appeared in the following issue and it was signed by “Lyra” in Bridgewater. The next year, 1848 we find the Primitive Expounder, a Michigan Universalist publication welcoming “LYRA” to its columns saying, “articles so beautifully and correctly written is [sic] pleasing to the eye of the printer.”

Rev. Dolphus Skinner, one of the editors of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, recommended Fidelia’s father to fill an empty Universalist pulpit in Pontiac, Michigan so in May 1847 the Woolley family traveled west to Michigan via the Erie Canal and a Great Lakes steamer. They settled on a small farm about two miles west of Birmingham. Her father preached alternately in Pontiac and Birmingham while Fidelia took a teaching position in a district school.

She put her first three years in Michigan to good use, learning algebra, geometry, French, astronomy, and botany. In later years she recalled reading Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845) by Margaret Fuller with her father. She read the “Declaration of Woman’s Rights” from the Seneca Falls Convention a month after it was issued in the August 24, 1848 issue of the Primitive Expounder.

In an 1851 story by Lyra titled “Lizzie Brown,” we learn about a young woman much like Fidelia, who has been teaching school for three years. Fidelia describes Lizzie’s room where, “. . .the book-case shows the names of eminent historians, novelists, poets, statesmen and reformers.” Fidelia reveals her own interests when she continues the description saying, “Here upon the table, are her Latin and Greek books; and open, his Margaret Fuller Ossoli’s Woman in the Nineteenth Century, and close beside it, Madame De Stael’s Corinnae. Upon her portfolio . . . a just finished drawing of the birthplace of Sir Isaac Newton . . . .”

In Rochester, Michigan, Fidelia could participate in the Avon Lyceum, a private high school led by Robert Clark Kedzie. An Oberlin graduate, Kedzie brought Antoinette Brown [later Blackwell] to teach at the Avon Academy for a year. Another local influence was Rochester resident, Calvin Harlow Greene, a local mill owner and an ardent Transcendentalist. Greene, in a four year correspondence with Henry David Thoreau, requested and received books and a daguerreotype portrait from Thoreau. Greene led the academy after Kedzie left.

Fidelia’s mother visited Michigan in 1848 but soon returned to her parent’s home in Nelson, New York. Fidelia’s father continued preaching regularly even as his health worsened, but he also set about putting his earthly affairs in order by encouraged his three older daughters to marry, looking to place his young children with neighbors, and divorcing his wife in 1851 because of her “unkindness and desertion.”

Fidelia was courted by a local bachelor, Hartson Gillette. Twelve years her senior, Hartson worked and lived on his father’s nearby farm. They were married on December 23, 1850 by her father and they moved into a house two miles north of Birmingham, where their only child, Florence Lillian Gillette was born on October 3, 1851.

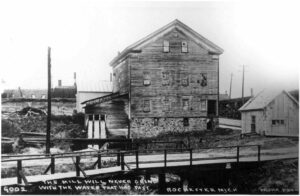

Hartson Gillette’s family was from Bloomfield, Connecticut where they had attended the Congregational church. Hartson’s brother Baxter had a farm nearby until the mid-1850s when he sold it to start a milling business in Rochester, Michigan. Hartson joined his brother Baxter running the Rochester mill. Another brother, Jacob Mills Gillette had embraced Millerism in the 1840s. He lived nearby on a 240-acre communal farm led by Uri Adams. Adams and his followers had been Millerites, but they had moved on to Second Adventism after the world failed to end on October 22, 1844, the date predicted by their leader, William Miller.

Fidelia continued to write and publish articles and poems after her daughter was born. They appeared regularly from 1849 to 1872, mostly in The Ladies’ Repository, a Universalist monthly published in Boston. She also collected her father’s notes, letters, and journals to write her first book, Memoir of Rev. Edward Mott Woolley (1855). She was assisted with the book by A. B. Grosh, editor of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate.

In the early 1860s, the Gillette family moved into Rochester, a town of 500 people. Detroit, 25 miles to the south had 70,000. Rochester was located at the junction of the Clinton River and Paint Creek and was connected to the Great Lakes by the new Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal. Rochester had an abundance of water power which Hartson and his brother Baxter used to power their flour mill. In 1863 the town had two water-powered woolen factories, a paper mill, three saw mills, and four flour mills. It also had a Universalist Society that had been organized in 1838.

A frequent visitor to the Gillette home in Rochester was Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker, the standing clerk of the Michigan Universalist Convention, 1855-70; and the minister at the Lansing Universalist church, 1853-60. After 1860 he regularly preached in Rochester, sometimes twice a month. He lived in Wayne, Michigan but had a regular circuit of churches including; Farmington, New Hudson, Southfield, Corunna, Pontiac, and Rochester. As a latter day circuit-rider he rode the trains, often two or three times a day. He would stay with parishioners when services were repeated in the evening. A May 8, 1863 note in his diary says, “Call around. Find Mrs. Gillett in trouble. From my soul I pity her. How dreadful to have a discontented drinking husband.”

A frequent visitor to the Gillette home in Rochester was Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker, the standing clerk of the Michigan Universalist Convention, 1855-70; and the minister at the Lansing Universalist church, 1853-60. After 1860 he regularly preached in Rochester, sometimes twice a month. He lived in Wayne, Michigan but had a regular circuit of churches including; Farmington, New Hudson, Southfield, Corunna, Pontiac, and Rochester. As a latter day circuit-rider he rode the trains, often two or three times a day. He would stay with parishioners when services were repeated in the evening. A May 8, 1863 note in his diary says, “Call around. Find Mrs. Gillett in trouble. From my soul I pity her. How dreadful to have a discontented drinking husband.”

Hartson Gillette was industrious and a good provider but fell short as a helpmate and parent. In an 1861 article in The Ladies Repository “Leaves from a Sick Room: Number 8,” Fidelia writes, “Many a husband chafes like an angry lion at bay, beneath the daily anxieties necessary to family happiness.” Daily anxieties like cooking, cleaning, and caring for sick children. Knowing first hand the family toll of alcohol use, she helped found the Rochester Good Templars Lodge in 1864 and was elected to serve as the Worshipful Vice Templar.

In Feb 1864, Hartson enlisted in the twenty-second Michigan Infantry regiment at Pontiac, Michigan. He was mustered out in Detroit after serving 18 months. According to a latter newspaper account, “He was a man of generous impulses, tender affections and metaphysical thought,” but, “. . . his health was ruined in the service.”

On December 7, 1864, Michigan Universalist Convention standing clerk Knickerbacker delivered the sermon at the ordination of Augusta Jane Chapin in Lansing, Michigan. Chapin was the first women ordained to the Universalist ministry in Michigan. Two weeks later Knickerbacker was in Rochester preaching to the Universalist Society on New Year’s Day. The society was still meeting in a schoolhouse or public meeting hall. First organized in 1838, the Rochester Universalist Society wouldn’t build a church until 1868. Church records are long lost, but it was later recorded that Fidelia’s younger sister Esther Almira “. . . was a prominent member of the Universalist Church, and it was to her large executive ability and her thorough and constant service to all its interest, that the church owed its prosperity.”

The Gillette family did well in Rochester. According to the 1872 plat map, Hartson owned 4 acres near the center of town, Baxter owned 15 acres with water power rights and a flour mill, and Mrs. Gillette had a 2 acre tract of her own, on the river across from the Barnes Brothers paper mill. When her husband’s brother sold the flour mill and returned to farming in 1876, Hartson joined with J. C. Romine to build a new mill farther up the Clinton river at Auburn, Michigan.

Universalist women increasingly moved onto the public stage during the Civil War, especially in the new states of the old Northwest Territory. Easterners Daniel and Mary Livermore had moved to Chicago, Illinois in 1857 to take charge of The New Covenant, a Universalist Weekly. Before the Civil War, the Livermores, in New Covenant essays, addressed female suffrage, women as public orators, the training of women doctors, and woman’s rights. During the war Mary Livermore took a lead role in the organization of a series of sanitary fairs to support soldiers and the war effort. After the war, she turned her attention to encouraging Universalists to make room for women. The Northwestern Conference of Universalists took up the challenge starting a “Woman’s Missionary Movement,” and electing four women as conference vice-presidents. Western Universalists preferred the liberal Chicago-based New Covenant over the Boston-based Universalist journals. Fidelia was a New Covenant agent and friend of the Livermores. Illinois Universalist women formed an organization in 1868 to raise funds for Lombard College in Galesburg, Illinois. The following year a similar national organization, the Women’s Centenary Association was formed at the Buffalo convention.

Fidelia helped form a literary society in her home town of Rochester in 1872, and the following year she presented one of the six lectures on its inaugural program. Up until then, her articles and stories had regularly appeared in the Universalist Ladies’ Repository. After that, reports of her public speaking and ministerial career became more frequent while her published output waned. It is possible that Fidelia joined Mary Livermore and others in snubbing the Ladies’ Repository after the Boston based North East Publishing House fired the editor Phoebe Hanaford for supporting the right of women to preach.

Early in her marriage, Fidelia had decided to avoid the public arena and tend to her family until her daughter Florence was fully grown. That point came dramatically in 1873 when Florence joined a Chicago theater company that was touring Michigan with a production of Jane Eyre. Fidelia’s reaction when her daughter ran off wasn’t recorded, but for someone who so valued family relationships it must have been a painful separation. On the other hand, her daughter’s departure did free Fidelia to take to the public stage.

Early in her marriage, Fidelia had decided to avoid the public arena and tend to her family until her daughter Florence was fully grown. That point came dramatically in 1873 when Florence joined a Chicago theater company that was touring Michigan with a production of Jane Eyre. Fidelia’s reaction when her daughter ran off wasn’t recorded, but for someone who so valued family relationships it must have been a painful separation. On the other hand, her daughter’s departure did free Fidelia to take to the public stage.

On August 20, 1873, Fidelia petitioned the Michigan Universalist Convention for a license to preach. The committee approved her application the following day. In July of that year she gave a Temperance speech in Pontiac and then in October she delivered another at Owosso, Michigan. The next year when the Michigan State Woman Suffrage Association met in Rochester they selected Fidelia to represent the organization at the state capital in Lansing. In the fall of 1874 she led services at the Unitarian Church in Detroit that her brother Smith Rensselaer Woolley attended.

When the sixth annual meeting of the National Woman Suffrage Association met in Detroit in October 1874, it was Fidelia who opened the meeting with a prayer. This was followed by an address from Elizabeth Cady Stanton who was wrapping up a month of canvassing for suffrage in the state. Julia Ward Howe, Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Mary Livermore were also in attendance. On the third day of the convention, Fidelia delivered the closing address, “Why Women Should Have the Vote.” A short report by Antoinette Brown Blackwell followed.

On February 18, 1875, Fidelia was asked to deliver the opening prayer for the Michigan House of Representatives in Lansing. One week later on February 25 she delivered her lecture on “Fanny Forrester” in the state legislator’s hall. On the very same day, her daughter married Eugene Russell Soggs, an actor, in Chicago, Illinois. They were married at Chicago’s Universalist Church of the Redeemer by its new minister, Sumner Ellis. For someone who valued family and had doted on her daughter while she was growing up, it must have been a trial not to attend her wedding.

In addition to lectures and public appearances, Fidelia joined the staff of the Rochester Era newspaper where she would hold the title of women’s rights editor. The paper had good coverage of Universalist activities and women’s issues; one article noted the arrival of J. H. Palmer, as minister at the Rochester Universalist Church while another article praised the 1875 Michigan Universalist State Convention in Lapeer because over half of the delegates were women.

In 1875 Fidelia delivered the fifth Lecture and Library Association talk at Rochester’s Newberry Hall on “Boys and Girls.” The newspaper reported that Fidelia was, “. . . a thinker of uncommon breadth. Among the women of Michigan there are few possessed of finer or more varied attainments than Mrs. Gillette.” She also addressed the prisoners in the Detroit House of Correction that month. In May she bought half ownership of Truth for the People, a Detroit newspaper published, “. . . in the interest of woman, both morally and politically.”

Like her father, Fidelia had no formal theological training. Universalist ministers in the first half of the nineteenth-century were usually tutored or mentored by established Universalist preachers. They learned by participating in worship services, association meetings, and state conventions. They often lodged at one another’s homes as they traveled. Fidelia, with her father, had attended services led by Universalist circuit-riding ministers; Nathaniel Stacy, John Freeman, and Stephen Rensselaer Smith. She also had corresponded with publishers like A. B. Grosh and Dolphus Skinner and had read Universalist weekly papers and monthly journals since childhood.

Fidelia took a half-time preaching position with the Universalist church in Concord, Michigan in 1876. She was ordained in the Manchester, Michigan church on February 8, 1877. The Owosso American newspaper said, “. . . recently ordained to the ministry by the Universalist Convention at Tecumseh, [she] will serve as State Missionary of that denomination.” That summer she preached at Paw Paw and Marshall, Michigan where she organized a new Universalist Society.

In the fall she was called by the Universalist society in New Sharon, Iowa. There were 36 members worshiping in a new $3,000 wood church. Fidelia preached in New Sharon until October 1879. Her second book, a collection of 125 poems titled Pebbles From the Shore was published in New Sharon in that year. While in Iowa, Fidelia served with Florence Kollock as co-chair of the Iowa Centenary fund. She also served as the pastor at the Universalist church in Mitchellville, Iowa. It had been organized in 1868 and the Iowa Universalist Convention opened the Mitchell Seminary nearby in 1872. Funded by and named for the prominent local Universalist Thomas Mitchell, the seminary closed in 1880 and the state of Iowa bought it for use as a girl’s reform school.

During the 1880s, Fidelia lived in Rochester, Michigan and divided her time between writing and Universalist missionary work. With her daughter she co-authored a book of stories and poems, Floating Leaves (1881). Five hymns that she wrote were published in The Morning Light! Hymnal (1880), a collection published by Solomon W. Straub. Solomon’s brother Jacob and sister Mary were Universalist ministers from Dowagiac, Michigan. And, after being absent from Universalist publications for a dozen years, Fidelia had five articles printed in Manford’s Magazine (another western publication from Chicago) during 1885.

In 1882 Fidelia visited Delphos, Kansas to deliver a number of sermons and lectures. She was in Kansas again the next year to attend the State Convention of Universalists in September. The Kansas convention met in the new Junction City church and Fidelia spoke on Sunday School Interests. In 1885 Fidelia attended the Missouri state Universalist Convention. These state conventions, held in cities on the new western railroad lines, featured leading Universalist ministers and denominational editors from across the continent.

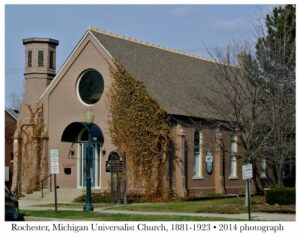

Chauncy W. Knickerbacker, clerk of the Michigan state convention preached alternate Sundays at the Rochester and Washington churches in 1880-81. According to his diary, he often stayed with “Mrs. G.” in Rochester, sometimes from Friday through Monday. On other Sundays he was in the pulpit in Farmington or Bay City, Michigan, both easily accessible by new rail lines. Midweek he traveled to Canada via Detroit and the Grand Trunk Railway to lead Wednesday evening services for the Blenheim and Olinda congregations in Ontario. The Rochester Universalist church had burned down in 1874 so they were meeting in rented rooms again. In 1881 a new brick church was built in Rochester. The Detroit, Michigan and Olinda, Ontario congregations also dedicated new Universalist churches that year.

Chauncy W. Knickerbacker, clerk of the Michigan state convention preached alternate Sundays at the Rochester and Washington churches in 1880-81. According to his diary, he often stayed with “Mrs. G.” in Rochester, sometimes from Friday through Monday. On other Sundays he was in the pulpit in Farmington or Bay City, Michigan, both easily accessible by new rail lines. Midweek he traveled to Canada via Detroit and the Grand Trunk Railway to lead Wednesday evening services for the Blenheim and Olinda congregations in Ontario. The Rochester Universalist church had burned down in 1874 so they were meeting in rented rooms again. In 1881 a new brick church was built in Rochester. The Detroit, Michigan and Olinda, Ontario congregations also dedicated new Universalist churches that year.

Fidelia’s husband had been granted a military pension in 1872, eight years after he was mustered out of service. Hartson suffered from “sunstroke,” a common diagnosis for Civil War soldiers with symptoms of head pain, loss of energy, mental problems, and heart conditions. Their daughter Florence took care of him after 1883 in Rochester, finally taking him to New York City where he died in April 1886. Hartson was buried “across the sound” in Connecticut. A month later Fidelia applied for the widow’s benefit of his Civil War pension.

The record isn’t clear on Fidelia’s financial circumstances after the death of her husband. It’s possible that he left her some land and money. It’s also possible that her nephew Clarence Mott Woolley, a successful industrialist provided some financial assistance. Fidelia’s brother Smith Rensselaer Woolley along with his son Clarence Mott Woolley had eschewed the ministry to pursue more lucrative lines of employment: Smith Rensselaer took up distilling while Clarence Mott went into management and manufacturing.

In 1887 Fidelia was asked to officiate at the dedication of the new Universalist church in Nixon, Ontario. Nixon along with churches at Bloomfield, Smithville, Port Dover, Blenheim and Olinda were part of the Ontario Universalist Convention. Stephen Herbert Roblin, raised a Methodist in Bloomfield, Ontario, had recently taken the Universalist pulpit in Bay City, Michigan. Except for Bloomfield, these small Canadian congregations were close to the Grand Trunk mainline connecting Boston with Chicago so they often hosted denominational officials, noted preachers, and religious journalists who were traveling the Boston-Chicago route. The Bloomfield church had been founded in 1846 by David Leavitt, a central figure in Canadian Universalism. For forty years his missionary work had encompassed the land from the Ottawa River to the river Detroit. When he retired in September 1887, Fidelia was called by the Bloomfield, Ontario church to replace him.

She started in April 1888 at a salary of $500. Three months later she conducted David Leavitt’s funeral service with the assistance of Rev. Roblin. When the Ontario Universalist Convention met at Bloomfield that year, a resolution congratulated the church on “the evidence which we see of genuine wisdom of their choice of pastor.” The church also received support from the Universalist Woman’s Missionary Society of Massachusetts. They sent books for the Bloomfield Sunday school library and $100 to Gillette, “. . . as an increase in salary.” That winter she encouraged the young people of the Bloomfield church to put on a literary and musical entertainment. It included a performance of “The Beautiful Life,” a hymn written by Fidelia. She would also deliver a sermon in nearby Orono, Ontario.

During the 1880s, Fidelia’s daughter, the actress Florence Gillette, toured the country with a variety of troupes including one of her own. At home in Chicago she taught stage elocution and voice-culture. On July 9, 1889, Florence married a second time; to a Chicago bookkeeper and actor, George A. Flett.

Fidelia published Editorials and Other Waifs, a book of aphorisms in 1889. That fall she relinquished her ministry in Bloomfield, Ontario and returned to her home in Rochester, Michigan. In an essay titled “Woman and Religion,” Fidelia wonders why women, “. . . can go firmly forward in the winding path that leads to our Father’s door.” Having lived longer than most of her family she asks “. . . where can she cling in her weakness? Upon whom can she lean, in her weariness? Where can she turn in her utter desolation?”

She left Rochester once again in 1892, this time to minister to the Universalist congregation in Standing Stone, Pennsylvania. When she returned to Rochester in 1896 she helped found the Rochester Woman’s Club. Her daughter Florence’s second marriage failed, and Florence, now suffering from paresis, came home to Rochester once again. Fidelia cared for her daughter until she died in 1900.

She left Rochester once again in 1892, this time to minister to the Universalist congregation in Standing Stone, Pennsylvania. When she returned to Rochester in 1896 she helped found the Rochester Woman’s Club. Her daughter Florence’s second marriage failed, and Florence, now suffering from paresis, came home to Rochester once again. Fidelia cared for her daughter until she died in 1900.

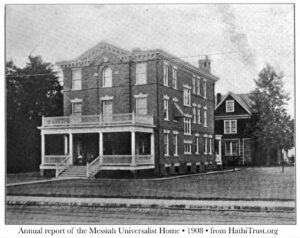

The Rochester Era newspaper reported that Fidelia wanted to have the remains of Hartson and Florence buried in Philadelphia’s Ivy Hill Cemetery and that she planned to live nearby. Something prevented Florence’s burial, so a year later Fidelia accompanied her daughter’s body to North Pomona, California for burial. According to the Los Angeles Herald, Florence had, “. . . passed away at her childhood home near Rochester, N. Y. [Michigan], July 19, 1900, a victim of paresis, after a lingering illness of five years.” Fidelia then entered the Messiah Universalist Home in Germantown, Pennsylvania in 1903, one year after it opened.

She penned one last item, a 1905 letter to the editor of the New-York Tribune. “I have known several millionaires and a few multi-millionaires, but they were neither illiterate nor ill-mannered,” she wrote, “In fact, when I want to help some suffering human brother or sister and find myself with an empty pocket, I am thankful for the millionaires. What would this dear old world do without them?” Was this a final tribute to her brother Smith Rensselaer Woolley and her nephew Clarence Mott Woolley?

Fidelia died a few months later. The Messiah Home covered her funeral expenses and she was buried in Philadelphia’s Ivy Hill Cemetery, next to Hartson. Universalism faded in Rochester, Michigan, and the Universalist church was sold to Seventh Day Adventists in 1923.

According to a short biography in Catherine F. Hitchings, Universalist and Unitarian Women Ministers (1985), Fidelia left her father’s works and her unpublished writings to Osgood G. Colegrove and his nephew, Rev. G. F. Thompson. Those items now appear lost. The Reverend Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker papers in the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, contain a number of clippings and references to Fidelia as do the Universalist Church papers in the Prince Edward County Archives in Picton, Ontario, Canada. Additional information, including copies of the Rochester Era newspaper, can be found in the Archives of the Rochester Hills Museum at Van Hoosen Farm in Rochester Hills, Michigan. A 190-page unpublished and undated manuscript of Christmas stories written by Fidelia and her daughter Florence Gillette, Christmas Bells for Little Folks , is in the archives of the Owen D. Young Library at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York. Special thanks to writer Maureen Thalmann of Rochester Hills, Michigan and to Woolley family historian Dave Woolley for additional historic materials and research assistance.

Two recent biographies are Jean Pfleiderer, “Tender and True: the Reverend Mrs. Gillette,” in Invisible Influence: Claiming Canadian Unitarian Universalist Women’s History (2011) and Joan W. Goodwin “Biographical Sketch of Lucia Fidelia Wooley Gillette” in Dorothy May Emerson, ed. Standing Before Us: UU Women and Social Reform 1776-1936 (2000). Earlier biographies are found in Catherine F. Hitchings, Universalist and Unitarian Women Ministers (1985); Eliza Rice Hanson, Our Women Workers (1882); Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Universalist General Convention 1906 ; and W. A. Fox Beautiful Rochester: A Sketch of a Live Town (1897). Biographical entries are also found in American Women: Fifteen Hundred Biographies: Volume I (1897), edited by Frances E. Willard & Mary A. Livermore, and Herringshaw’s Encyclopedia of American Biography of the Nineteenth Century, Thomas William Herringshaw, ed. (1901).

Valuable secondary sources include; A. G. W. Lamont, David Leavitt, His Relationships, and the Bloomfield Universalists (Picton, Ontario 1993); Louise Foulds, Universalists in Ontario (1980 & 2005); Gwen Foss, transcriber, Diaries of The Reverend Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker, Universalist Minister: 1843-1884 (2007); and Cynthia Grant Tucker Prophetic Sisterhood: Liberal Women Ministers of the Frontier, 1880-1930 (1990). Numerous reports on Fidelia’s activities can be found in issues of The New Covenant, the Gospel Banner, and The Primititive Expounder available at Google Books or the HathiTrust.org library. Additional coverage can be found in the Chronicling America digital archives at the Library of Congress website, in Michigan County Histories available on the University of Michigan website, and in issues of the Detroit Free Press available through Newspapers.com. Obituaries appeared in the Universalist Register (1906) and a number of Pennylvania newspapers including the Philadelphia Inquirer, Bradford Argus, Bradford Star, and the Bradford Reporter Journal.

Bibliography of stories, essays, books, hymns, and poems

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted March 2, 2016